Bringing Back the Hainan Lion

The unexpected find of a cape with tiger markings in the storeroom of the Guang Wu Club led a martial artist and lion dance master to revive a lost art form in Singapore.

By Angela Sim

2 December 2025

When martial artist and lion dance master Raymond Foo, the head of 光武国术团 (Guang Wu Guoshu Tuan or Guang Wu Club), was about 15 years old, he chanced upon a cape with tiger markings in the club’s storeroom. He had come across the Hainan lion in photos and trained in martial arts and lion dance since he was 12, but no one could tell him what this striped cape was. His quest for answers brought him to Hainan Island and set him on a path to reviving and preserving an art form lost to Singapore.

Detail of the Hainan tiger cape found in the storeroom of Guang Wu Club. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Detail of the Hainan tiger cape found in the storeroom of Guang Wu Club. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.An advocate of all things Hainanese, Foo has more than 50 years’ experience in martial arts and lion dance. Established in 1936, Guang Wu Club is the only organisation in Singapore that promotes the elusive Hainan lion dance (海南狮; Hainan shi), also known as 琼州狮 (_Qiongzhou _shi), the Hainan tiger dance (海南虎; Hainan hu) and Hainan qiong pai martial arts (琼派功夫; qiong pai gong fu). Even though the Hainan tiger dance is rarely performed in Singapore today, its influence on Hainan lion dance can still be seen.

The Hainan Tiger

In 2016, Foo went to Hainan Island to find out more about the origins of the mysterious tiger cape. He started his journey in Luowu Village in Sanjiang Town, Melian District, Haikou Hainan (海口市美兰区三江镇罗梧村; Haikoushi meilan qu sanjiang zhen luo wu cun), said to be the home of the Hainan tiger dance, which has a history of more than 300 years.

When Foo saw the full Hainan tiger at Luowu Village, he was astonished that it bore many similarities to the Hainan lion head in Gwang Wu’s possession in Singapore. The Hainan tiger had been brought to Singapore in the 1960s but it did not appeal to the masses, and thus rarely performed. At the time, the people were much more familiar with the Southern or Foshan (佛山), lion dance from Guangdong, especially during the Lunar New Year, and preferred a lion over a tiger to perform the “plucking of greens” (採青; cai qing) ritual to usher in good fortune and tidings.

A Hainan tiger dance costume in Sanjiang Town, 2016. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.

A Hainan tiger dance costume in Sanjiang Town, 2016. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.The tiger dance is a tribute to the bravery and strength of Lady Xian (冼太夫人; Xian Tai Furen, c. 522–602 AD) and is still performed today during the annual Junpo Festival (军坡节; Jun Bo Jie) celebrated between the first and third lunar months (around February and March) on Hainan Island in the town of Xinpo. A rich cultural and religion event, the festival coincides with the start of spring and the tiger dance is performed to pray for a bountiful harvest, clement weather, the safety of animals and people and prosperity.1 Lady Xian’s father was the chieftain of the Xian clan (or Baiyue) of the Li people in Southern China (modern day Guangdong). She was a politician and militarist who fostered good ties among neighbouring clans as well as with the Han Chinese.2 Her people were frequently embroiled in conflict with other clans, which she sought to prevent through diplomacy and negotiation.

However, her brother, Xian Ting (刺史), the governor of Nanliangzhou (南梁州), had grown arrogant and greedy from wealth acquired largely through trade with the Han Chinese. He would harass nearby counties and seize their possessions, causing widespread suffering in the Lingnan (岭南) region. Lady Xian repeatedly advised her brother against such actions, gradually easing public resentment toward him. She promoted political unity and cooperation among the various ethnic groups in the Lingnan region and devoted her life to building racial harmony between the Li people and the neighbouring communities and growing the local economy by developing agriculture after witnessing the suffering and disasters caused by war.

One of her notable reforms was the abolishment of the Li people’s traditional servitude system, which helped integrate her people more closely into the broader social and political structures of the Southern Dynasties (420–589 AD), while also improving social order and justice.

Tiger heads from Sanjiang Town, 2024. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.

Tiger heads from Sanjiang Town, 2024. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.The tiger dance was introduced to Hainan from the Central Plains during the Ming Dynasty and is still popular in the rural areas around Sanjiang Town. The Hainan tiger dance features routines such as fighting tigers and solo tiger performances. Each dance troupe comprises about 20 to 30 performers, and each tiger requires two dancers – one as its head and the other as the tail. While the tiger dance features movements similar to the Hainan lion dance, its dancers adopt a much lower stance than that of the Hainan lion, allowing them to draw strength from deep, rooted stances that mirror the animal’s low, prowling gait. The tiger’s force — 虎劲 (hu jin) — rises from the ground, gathering in the dancers’ hips and spines before releasing in sudden, explosiveness (爆发力, baofali) that give the dance its unmistakable power. In embodying the tiger, every crouch, creep and pounce depends on staying close to the ground, allowing the dancers to channel the creature’s stealth, tension, and raw momentum. Other troupe members take on roles such as soldiers and deities – namely the Chinese earth god 土地公 (Tu Di Gong) and his wife 土地婆 (Tu Di Po).3

A Haikou Hainan tiger head gifted to Guang Wu Club in 2009. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

A Haikou Hainan tiger head gifted to Guang Wu Club in 2009. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming. Detail of the Hainan tiger’s teeth. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Detail of the Hainan tiger’s teeth. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming. Tudi Gong (top) with multiple Huye (tiger deity) and Tian Gou (bottom left) and Hei Hu Jiang Jun (the tiger general, middle) at Poh Tiong Beo Temple in 2022. Courtesy of Angela Sim

Tudi Gong (top) with multiple Huye (tiger deity) and Tian Gou (bottom left) and Hei Hu Jiang Jun (the tiger general, middle) at Poh Tiong Beo Temple in 2022. Courtesy of Angela SimThe effigies of Tu Di Gong and Tu Di Po and Huye (the tiger deity), or the tiger general (虎将军, Hu Jiang Jun, who falls under the tutelage of Tu Di Gong), are often seen together beneath the main altar of most Taoist temples, watching over and protecting the local community. The tiger dance dramatises the struggle between humans and tigers, showing how people use intelligence, skill and martial prowess to overcome these formidable creatures. Once the tiger is subdued, the dance celebrates the possibility of harmony, symbolising a balance between human courage and respect for nature.4

However, overshadowed by the popular Foshan, or Hoksan (鹤山) Cantonese Southern lions, the tiger dance subsequently faded into obscurity – and into Guang Wu’s storeroom.

The Guang Wu club’s Hainan tiger (left) and lion (right). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

The Guang Wu club’s Hainan tiger (left) and lion (right). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Early Hainan Lions

In the early 1950s, Guang Wu Club hired Feng Anbang (冯安邦) as a martial arts and lion dance coach in an attempt to revive the Hainan lion dance, which, due to difficulties in dance stances and construction of the lion’s head, had not been widely performed. Guang Wu martial arts elder Lin Youhe (林猷和师傅) remembered watching a Hainan lion performance only once in his life – in 1941, when he was seven. This was also the last known performance of the Hainan lion dance in Singapore. The Hainan lion performers from the Nanmei Association (南梅同乡会), who were trained by Qiongzhou master Lin Hongyi (琼州拳师林鸿仪), had performed at a national salvation and relief event organised by the Chinese community in Singapore in support of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45).5

Feng Anbang as the head of the Hainan lion (right), 1961. Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.

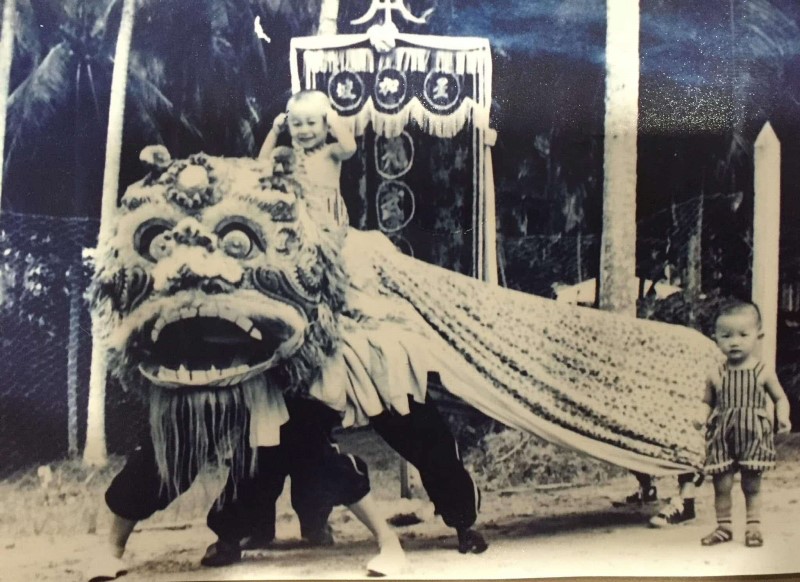

Feng Anbang as the head of the Hainan lion (right), 1961. Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.Feng synthesised elements of the Hainan tiger dance with the performance techniques of the Southern (Foshan) lion dance for the movements of the Hainan lion. These movements are more aggressive, unlike the Southern lion which has a more docile and cuter demeanor. Guang Wu’s distinctive Hainan lion dance was based on referencing its archival black-and-white photographs and the oral testimonies of its senior practitioners, along with steps from the Hainan tiger dance. In 1958, Feng commissioned a lion head which was made in Malacca, Malaysia, which he brought back to Singapore. Three years later, in 1961, the Guang Wu Club commissioned another Hainan lion. In 1967, at the first National Martial Arts Performance Competition hosted by the People’s Association, Guang Wu performed their routine, 三叉大扒镇狮 (sancha da ba zhen shi) with the two Hainan lions, which was their last public performance until 2016.

The Hainan lions at the first National Martial Arts Performance Competition hosted by the People’s Association, 1961. Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.

The Hainan lions at the first National Martial Arts Performance Competition hosted by the People’s Association, 1961. Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.Guang Wu’s Hainan lion and the Foshan lion from Guangdong share a historical lineage, with Guang Wu’s lions hailing from a specific branch of the Qiongzhou tradition known for features such as the lion’s facial features, expressive gestures and footwork. The Arhat (big-headed Buddha) similarly shares a historical lineage with the Guang Wu lions via Qiongzhou. The Hainan lion’s head is designed in the likeness of an Arhat (a big-headed Buddha), with a prominent mouth and fangs that convey strength and grandeur – traits associated with the Arhat as a guardian figure. The Hainan lion is made from materials such as sandpaper, bamboo, rabbit fur and horsehair, and features tiger stripes, colourful pom-poms and Tang-style motifs (such as swirling cloud patterns, vegetal motifs, stylised florals and geometric outlines). While its eyes and overall form might differ, most elements are consistent with the Southern lions, reflecting shared design traditions and motifs reminiscent of Guangdong and Fujian artistic heritage.6

An early Hainan lion, c.1950s. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.

An early Hainan lion, c.1950s. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.According to a senior Guang Wu member, the heads of the first-generation Hainan lions were made of layers of paper pasted together using pig’s blood, which made them very heavy, each weighing about 10 kg. “The first-generation Hainan lion had a large round head and face [and was] much heavier than the average Southern lion,” said Foo. “This larger head is not easy to control, and it [was] quite difficult to dance [with]”.7

Like the Hainan tiger, the Hainan lion also had a relatively flat head. Compared with Southern lions, which were smaller, sharper and more delicate, the Hainan ones were seen less attractive due to their bulbous head, huge centrally positioned eyes and a big nose.

Guang Wu lion dance troupe, 1958s. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.

Guang Wu lion dance troupe, 1958s. Courtesy of Raymond Foo.Foo also said that a key difference between the Hainan and Southern lions is that “[Hainan lions have] no horn on [their heads] … and [their] eyes are more centred [in the middle of their faces]”.8 But the body structure of the Hainan lion was similar to that of the Southern lion, taking inspiration from the distinctive visual traits of Guangdong’s stone-carved lions: upright ears, a pronounced forehead, fierce eyes, a prominent nose and an upturned mouth. The Hainan lion’s nose is positioned in the centre of head when viewed from the front and resembled a garlic bulb, which is why craftsmen often refer to it as the “garlic bulb nose”.9

New Hainan Lions

Based on old photographs, Foo asked a master to recreate four Hainan lions. After a few performances, however, the Hainan lions failed to gain any traction. Foo believed that the lions’ movements were not domineering and powerful enough, and that the Guang Wu dance troupe needed more time to hone their skills. Those four lions were eventually put to rest.

Undeterred (and thanks to a sponsorship in 2022), Foo ordered a Hainan lion from Lai Holin (黎贺年), a Malaysian master from Long Xin Dragon and Lion Dance troupe (马来西亚龍芯武术龙狮团) in Kuala Lumpur. Unlike the earlier lions, this Hainan lion’s eyes faced forward, and appeared bright and energetic. Its hair was made of stiffer horsetail hair giving it a more imposing look. Like its predecessors, the lion did not have a horn on its head. Although it was much lighter at 5 kg, with the head weighing about 3 kg, it was still challenging for the Guang Wu lion dancers to carry out deft manoeuvres such as balancing on high poles. However, they “still aim[ed] to incorporate [the] traditional aspects [of Hainan lion dance] to pass down the culture and heritage of this folk art form [to the next generation]”.10

The Hainan lion made by Lai Holin in Kuala Lumpur. Hainan lions have no horn. Courtesy of Angela Sim

The Hainan lion made by Lai Holin in Kuala Lumpur. Hainan lions have no horn. Courtesy of Angela Sim Hainan lions have flatter faces compared to their Southern cousins. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Hainan lions have flatter faces compared to their Southern cousins. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming. A close-up of the Hainan lion cape. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

A close-up of the Hainan lion cape. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Hainan Lion Dance Performance

Besides enhancing the design of the Hainan lion, Foo also sought to improve the accompanying percussion of the dance. He acknowledged that “each lion troupe has a different drum method” and he “incorporated the drumbeats of the Hainan tiger [dance] as well as the Foshan lion [dance]” into the Hainan lion drumbeats, resulting in the three-star, five-star and seven-star drumming methods [三星 (sanxing),五星鼓法 (wuxinggufa),七星斗等 (qi xingdou deng).11 These drumming sequences dictate the lion’s choreography, indicating when it should leap, bow or shake its head. The changes introduced by Foo made the lion’s movements more fluid and flexible.

Raymond Foo made the traditional tempo of the percussions more upbeat. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Raymond Foo made the traditional tempo of the percussions more upbeat. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Both the Hainan lion and tiger dances begin with the shifu or trained senior troupe member blowing into a conch shell.12 This heralds the start of the performance, representing 冲天 (chongtian), or soaring to the heavens, a metaphor for great ambitions or achievements. The sound of the conch is also believed to purify the space and dispel negativity, creating a positive and auspicious environment for the performance.

Conch shells, much like the horn trumpet or bugle, have been used in China as far back as 1000 BCE13 for military signals, religious assemblies, funeral rites as well as a tool for relaying messages. It is also considered spiritual.14 According to Foo, blowing the conch takes “skill and practice… Getting the right sound can also be tricky, but once you master the technique, the buzzing vibration from your lips is magnified by the shell, creating a powerful, resonant tone, much like playing a bugle”.15

Raymond Foo blows into the conch shell to signal the start of the Hainan lion dance. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Raymond Foo blows into the conch shell to signal the start of the Hainan lion dance. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Specific weapons are also used during the Hainan lion dance for routines such as 单刀破狮 (dandao po shi), 双刀破狮 (shuangdao po shi), 关刀破狮 (guandao po shi), 棍棒破狮 (gunbang po shi), 板凳破狮 (bandeng po shi), and 盾牌破狮 (dunpai po shi). The broad sword (关刀, guandao) is noteworthy as it represents Lady Xian’s fight for equality, social stability and better lives for the clansmen. Each weapon-based sequence is carefully choreographed to showcase both combat skill; dramatic flair, adding an intense, theatrical dimension to the Hainan lion dance routines. Each routine allows the performers to demonstrate strength, timing, coordination and martial aesthetics, making the Hainan lion dance uniquely vigorous and expressive compared to other regional lion dance forms in Guangxi, Fujian and Chaozhou. For instance, in 棍棒破狮 (gunbang po shi, or “staff versus lion”), a staff or cudgel is used to challenge the lion, showcasing the quick reflexes and precise control of the performer.

Raymond Foo wielding the 双刀 (shuangdao). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Raymond Foo wielding the 双刀 (shuangdao). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming. Raymond Foo performing with the 双鱼撞 (shuangyudang or double fish shield). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Raymond Foo performing with the 双鱼撞 (shuangyudang or double fish shield). Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Troupe members representing the deities Tu Di Gong and Tu Di Po closely mimic the movements of the lion, with graceful, rhythmic steps. Then, with a sudden burst of energy, shouts fill the air as soldiers (兵勇, bingyong) appear, ready to take on the lions. The Guang Wu dancers bring the beasts’ nimble, swift movements to life, while the soldiers’ bravery and expert martial arts skills add to the thrill for a truly breathtaking display.

Tu Di Po (with white hair) and Tu Di Gong (with grey beard). Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.

Tu Di Po (with white hair) and Tu Di Gong (with grey beard). Courtesy of Guang Wu Club.The soldiers symbolise 武德 (wude) – the discipline, courage and strength underpinning the martial arts tradition. They embody human skill and valour, standing as obstacles that challenge the lion’s path. At the same time, they hark back to the militia traditions of Lady Xian: men trained in weapons and martial arts, prepared to defend their communities.

The soldiers’ confrontation with the lion reinforces Lady Xian’s philosophy that force is sometimes necessary but must always be balanced with order and the well-being of the society. When the lion prevails, or reconciles with the soldiers, it reflects her legacy of uniting force with virtue. More than a festive spectacle, the Hainan lion dance is a living folk memory of Lady Xian’s governance, where martial discipline and ritual display work together to protect the people.

A Hainan lion engages in battle with a pugilist holding a trident. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

A Hainan lion engages in battle with a pugilist holding a trident. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.The Path Forward

The foundations of the Hainan lion dance are closely linked to kung fu (Chinese martial arts), with an emphasis on endurance and core strength. Like kung fu, the basic position in any lion dance is the horse stance (馬步; ma bu), which is like a squat. In this position, the dancer’s weight is evenly balanced, providing strength and stability.

Each lion dance master contributes his own unique style to the performance. Today, dance troupes tend to focus on the dance itself, rather than mastering traditional kung fu forms that are crucial for manoeuvring the lion. Novices also take a longer time to master the moves as many can only commit to training once a week.

A Hainan lion dance routine. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

A Hainan lion dance routine. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.Lion dance in Singapore faces numerous challenges, including strict regulations on noise and limited availability of suitable locations to train. Troupes also face difficulties in attracting more students. According to Foo, many only want to sign up with friends. This is compounded by misconceptions, particularly by parents, that lion dance troupes are bad company comprising troubled youths, school dropouts and secret society members.16

In the face of waning interest, Foo believes that lion dance can only be passed down to the younger generations by continuous innovation and “more theatrical dance routine[s] which will excite audiences and leave them wanting to find out more about our Hainan lions”.17

Guang Wu Club’s Hainan lion dance troupe at Kheng Chiu Tin Hou Kong. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming.

Guang Wu Club’s Hainan lion dance troupe at Kheng Chiu Tin Hou Kong. Courtesy of Low Jue Ming. Angela Sim is a researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture and sunset industries, including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration and lantern making. Angela is a Singapore native and promotes the nation as a cultural destination. She has a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Japanese Art History and currently resides in Brisbane, Australia. Her work can be found on YouTube under the handle Hakka Moi.

Angela Sim is a researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture and sunset industries, including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration and lantern making. Angela is a Singapore native and promotes the nation as a cultural destination. She has a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Japanese Art History and currently resides in Brisbane, Australia. Her work can be found on YouTube under the handle Hakka Moi.Notes

-

“海南军坡节千年不衰,” -客家文化-中国华文教育网, published 2 May 2022, https://www.hwjyw.com/article/10059.html. ↩

-

Benjamin Henry Couch, Ling-Nam; or, Interior Views of Southern China, Including Explorations in the Hitherto Untraversed Island of Hainan (London, S. W. Partridge and Co., 1886), 334. (From National Library Singapore, call no. 951.03 HEN) ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Liu Mengxiao 刘梦晓 , “Sheng ji fei wuzhi wenhua yichan hainan hu wu: Hu wu sheng wei sanbai nian” 省级非物质文化遗产海南虎舞:虎舞生威三百年 [Hainan Tiger Dance, a provincial-level intangible cultural heritage: The majestic tiger dance has been performed for three hundred years], 人民网, 13 July 2020, http://hi.people.com.cn/n2/2020/0713/c231190-34151945.html ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Daniel H. M. Chan, “Chinese Lion Dance: The Development of a Traditional Performance Art,” Asian Folklore Studies 54, no. 1 (1995): 35–58.; Wong Siu-fai 黃少輝, Zhongguo wushi 中國舞獅 [Chinese lion dance] (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1990); Xiao Mei 肖梅, Hainan minsu wenhua 海南民俗文化 [Hainan folk culture] (Haikou: Hainan Publishing House, 2008). ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Chen Aiwei 陈爱薇 , “Cankao hainan hu duchuang hainan shī huxiao shī cheng” 参考海南虎 独创海南狮呼啸狮城, [Inspired by the Hainan Tiger, the unique Hainan Lion Roars Over the Lion City] 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 19 February 2023, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/lifestyle/culture/story20230219-1364575. ↩

-

Prakriti Anand, “What is a Conch Shell? History, Meaning & Uses in Hinduism and Buddhism,” Exotic India, 22 October 2021,https://www.exoticindiaart.com/article/the-conch-shell-or-the-shankha/. ↩

-

“Conch Shell in Buddhism,” Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia, last updated 6 January 2024, https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php/Conch_Shell_in_Buddhism.; Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩

-

Megan Elise Michael, “Lion Dance Troupes in S’pore Hard-pressed to interest the young in continuing the tradition ,” Straits Times, updated 21 November 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/lion-dance-troupes-in-s-pore-hard-pressed-to-interest-the-young-in-continuing-the-tradition ↩

-

Raymond Foo, interview with author, 2024. ↩