Textual and Civilisational Discourses in Hsu Yun Tsiao’s 1933 Diary in Patani

By Nicholas Y.H. Wong

Hsu’s Nanyang Studies: Under the Shadow of Siamese Historiography

Before co-founding Chinese-language Southeast Asian (Nanyang or South Seas) studies in Singapore in 1940, the Suzhou-born historian Hsu Yun- Tsiao (1905–81) sojourned as a teacher at Zhong Hua School (1933–36) in the Malay-Muslim region of Patani in southern Thailand.1

Known mostly for his academic and editorial work in South Seas Journal (Nanyang xuebao, 1940–), the popular South Seas Miscellany (Nanyang zazhi, 1946–48) and the children’s magazine Malayan Youth (Malaiya shaonian, 1946–48), Hsu also led his students from Nanyang University (or Nantah) on ethnographic trips; promoted translations from Burmese, Thai and Vietnamese; annotated a play about Zheng He; wrote classical Chinese poems; compiled volumes on the anti-Japanese war effort by Nanyang Chinese (1938–45) and the war crimes trial (1946); as well as produced Southern Chinese language glossaries and Malay-Chinese dictionaries. Working across media to promote Malayan identities in the postwar era, Hsu gave 15-minute-long radio lectures on local histories, later compiled into Collected Writings on Malaya (Malaiya congtan, 1961).

In contrast, Hsu’s early, pre-Singapore years have been not as well known in Nanyang historiography. Recently digitised by the National Library, Singapore (NLB) in May 2018, Hsu’s five unpublished diaries (1930–38) provide rare glimpses into his interwar Nanyang studies in Siam (now Thailand), which anticipate the geopolitics and scholarly politics of Nanyang studies in Singapore some 20 years later.2

In 1933, in his most detailed 400-page diary, Hsu noted his anticipation in receiving publications from Shanghai: “Jinan University’s Bureau of Nanyang and American Cultural Affairs (Nanyang Meizhou wenhua shiye bu) sent over a huge bundle of the Nanyang Newsletter (Nanyang qingbao).3 According to the subscription form it costs one baht, payable to Kaiming Press. I ordered 30 numbers, from vol. 1 number 1 through vol. 2 number 10”. [Diaries v.2: 131]. Other interwar Chinese publications on Southeast Asia, such as Nanyang Research (Nanyang yanjiu, 1928– ), were managed by this bureau through key figures such as Liu Shimu, Li Changfu and Yao Nan, who would later co-found the South Seas Society (1940– ) with Hsu in Singapore.4 Anxious yet excited by Japan’s state-sponsored study of the Nanyang (or Nanyo) in the 1920s, these Chinese intellectuals founded the Jinan Cultural Bureau in 1927.5 By producing original work and translating Japanese and Western writings on Southeast Asia, the Jinan scholars hoped to redirect intellectual-political energies from Japan, and foster closer ties to local Chinese newspapers and journals in Penang, Singapore, Malacca and Batavia (now Jakarta).

Entering the scene slightly later and based in the Nanyang itself, Hsu transformed the Western- and Japanese-influenced research of Jinan scholars by drawing on a variety of Thai, Malay and Burmese sources.6 Hsu arrived in Patani just after the 1932 Siamese Revolution by the People’s Party of Siam, which had partially overthrown the monarchy to introduce a constitution. Hsu witnessed the chaotic waves of royalist counter-revolution against Bangkok that culminated in the Bowaradej rebellion of October 1933. In 1932, the future Prime Minister Phibul Songkhram forced Chinese assimilation by reviving the Primary School Act of 1921 and the Private School Act of 1918, requiring Chinese schools, which were then private schools, to register with the government, effectively placing them under state control. The Thai language was also made the compulsory medium of instruction. Hsu joined and negotiated for the Chinese schools’ education movement (1933–36), which protested against these changes. By 1930, elite members from Teochew, Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka and Hainanese language groups in Siam had agreed to teach in Mandarin and consolidate a Chinese national identity.7 Lamenting his students’ lack of proficiency, Hsu had at times taught Chinese using English and zhuyin zimu (Mandarin phonetic alphabet) [v.2: 234]. But now, Chinese language class time had been severely curtailed and other courses had to be taught in Thai. Hsu had to learn Thai and pass a language examination within one-and-a-half years of arriving in Siam [v.2: 172–73].8

Purveying the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (Kuomintang) curricula of overseas Chinese education based on the civilisational mission of Zhonghua huiguan (c. 1900), the “umbrella” organisation for Chinese affairs, Hsu lobbied for Chinese autonomy and cultural upkeep against the new regime’s forced assimilation policies, which reversed prior arrangements whereby Chinese subjects had been protected by the Siamese monarch.9 In 1936, Hsu left Zhong Hua School and taught English at Bangkok’s National School of Science and Engineering.10 In 1938, Hsu left for Singapore after the fascist Phibun, now a Field Marshal, forced Chinese newspapers and schools – those not already closed by the government or voluntarily – to shut down nationwide.11

In this section of the essay, I examine the oft-overlooked influence of modern Siamese historiography on Hsu’s Nanyang studies. In Hsu’s estimation, the three most important scholars of Nanyang histories were the French Sinologist Paul Pelliot (1878–1945), Sino-Indian historian Feng Chengjun (1887–1946) and Prince Damrong Rajanubhab of Siam (1862–1943).12 The latter, though exiled to Penang after the Siamese People’s Party coup in 1932, had famously inaugurated the study of modern Thai history (prawattisat) by giving a “nationalist reading of the phongsawadan” (dynastic chronicles).13 “By 1930, Damrong had retired and was leading the effort to build the collection at Siam’s National Library by accumulating ephemeral texts”.14 As the “Father of Siam History” [v. 2: 275] and “the royal librarian-in-chief” who played a “crucial role in the establishment of the Thai territorial state during the late 19th and early 20th centuries”, Damrong gets Hsu’s stamp of approval:

Dafa told me: Thai people call the Head of the Royal Library

the “Father of Siam History” [บิดาของประวัติศาสตร์สยาม bida

khong prawatisat siam]; he who happens to be the only historian

in Thailand.

大发告余,谓暹人称皇家图书馆主任为暹史之父บิดาของประวัติศาสตร์

สยาม 蓋暹国惟一之历史学家也。

Lending a twist to Prince Damrong’s royal-nationalist reading of Siam’s history was playwright and politician Luang Wichit Wathakan (1898–1962) who wrote popular histories, plays and propaganda in the early 1930s, even before he became the chief ideologue for Phibun’s military, ethno-nationalist wartime rule. Luang Wichit’s version of world history borrowed heavily from Damrong’s traditional-style chronicles of “drum-and-trumpet history” but updated them to include the heroic deeds of common men and women in defending the nation.15 Drawing on German and Italian Fascism16 and their “militaristic view of the past”, Luang Wichit’s idea of culture (watthanatham) saw Thai subjects as part of a civilised nation (prathet siwilai) on equal footing with Western powers and irrevocably shaped the course of Thai modernity.17

Luang Wichit’s 12-volume bestseller Prawattisat Sakon [Universal History, 1929–31] impressed Hsu enough for him to translate its sixth and seventh books, Prawat Khong Sayam [History of Siam].18 Hsu also published excerpts on the Sino-Thai King Taksin (1734–82) as Xianluo wang Zheng Zhao zhuan (Biography of the Siamese King Zheng Zhao, 1936). Zheng Zhao, the Chinese name of King Taksin (Daxin) used by diplomatic envoys to Qing China, apparently had a Teochew-Chinese father and a Thai mother.19 In his diary, Hsu notes Luang Wichit’s description of Taksin’s mythic origins: “thunder shook the house” and “a snake curled up by the baby’s side”, which his father “took as an unlucky sign and ordered his servant to throw the baby into the river” [v. 2: 96]. Rescued by a Siamese warrior, Taksin was sent to a Buddhist monastery and mastered southern Min, Vietnamese and Indian languages.20 Taksin went on to serve as a governor and acquired the noble title Phraya Tak. He famously expelled the Burmese from the fallen Ayutthaya kingdom (1351–1767) and founded the Thonburi dynasty (1767–82). Taksin’s achievements, for Luang Wichit, recalled King Naresuan’s (1555–1605) resistance against Taungoo Burma’s (1510–1599) repeated siege of Ayutthaya. Taksin would have been a fit specimen for Luang Wichit’s earlier essay, “On Great Men” (1928), which included “Napoleon, Bismarck, Disraeli, Gladstone, Okubo Toshimichi (of the Meiji Restoration) and Mussolini”.21

Luang Wichit’s biography on Taksin venerated Siamese ambition and success. But Hsu’s selective, annotated translation of this act of hero worship had a different motive. In 1904, the Chinese reformist Liang Qichao (1873–1929) published a famous, short essay, “Biographies of China’s Eight Great Colonial Heroes” (Zhongguo zhimin bada weiren zhuan), which espoused the virtues of settler colonialism and puzzled over the paradox of a large Chinese diaspora that had no formal overseas colonies.22 Liang named King Taksin as one of the great colonial heroes, among other southern Chinese traders and bandits who settled as far as Java and Sumatra. Under the pen name “China’s New Citizen” (Zhongguo zhi xinmin), Liang argued that “Taksin’s accomplishment as a Siamese king far exceeded the Japanese Yamada Nagamasa’s rule” (1617–30) in Siam’s Nakhon Si Thammarat province, but expressed “sorrow that his Chinese fellowmen did not know of [Thaksin]”.23 For Liang, the Chinese nation was constituted by the strengths of its diaspora.24 Even his call for a Chinese “poetic revolution” in 1899 was based on his favourable view of European colonial expansion as a solution for the problems of land exhaustion and overproduction.25 When situated in this tradition, Hsu’s translation of Luang Wichit’s Taksin reminds its readers, ironically, of the open secret of a Chinese bloodline of Siamese monarchs – even those from the later Rattanakosin period (1782–1932) who suppressed Taksin’s legacy to define their rule – and of the nationalist writer himself, Luang Wichit (whose given name was Kim Liang); Luang denied his Chinese heritage all his life. Whether hesitant to engage in anti-imperialist critique, or performing one based on ethnic injury, Hsu saw an appeal in ethnonationalist Thai histories that otherwise would affront him – or at least, the need to unearth a history of peaceful relations between Siam and China appealed to him. The figure of Taksin becomes a perverse form of what Benedict Anderson calls nationalism’s “unbound seriality”.26

I further suggest that the popular or “anecdotal histories” (shihua) that Hsu often published in postwar Singapore, with their emphasis on writing a people’s history, were inspired by Luang Wichit’s examples rather than by Chinese “literary biographies” in the style of Sima Qian’s Shiji [Records of the Grand Historian, c. 94 BC]. Hsu prided himself on rectifying place-name mistakes in classical Chinese accounts of maritime geography, for example, “Dani” was actually Pattani, not Borneo; “Dandan” was Kelantan; “Chitu” was Songkhla.27 Hsu’s biographer Lew Bon Hui (Liao Wenhui) traces Hsu’s textual analyses to the late-Qing scientific mode of “evidential learning” (kaozheng) or Han learning (Hanxue), which replaced earlier cosmological readings of classical texts with linguistic scrutiny, and suggests that this style of historical writing is found in Hsu’s primary school textbooks on Malayan history.28 Others prefer to call Hsu’s method one of “empiricism” (shizheng), based on models of Western social science that Nanyang historians, such as Liu Shimu, encountered when studying in Japan.29 Hsu remained aloof from revisionist trends in modern Chinese history such as that of Liang Qichao’s “New Historiography” (xin shixue), which recommended a causal (or evolutionary) approach focused on “popular movements and social life” attuned to “the world, nations, and peoples” and its “broader geographical and ethnic framework”, to replace the “reign-by-reign approach” of “Han China and its dynastic regimes”.30 Hsu hardly commented on the relationship between history and narrative, nation and ethnicity, but he had an implicit relation to Chinese scholarship about “frontier history” (bianjiangshi) and “China-foreign communication history (Zhongwai jiaotongshi).31

When he introduced his compiled lectures on Malaya, Nanyang, Annam and Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) at Nanyang University and Ngee Ann Institution, Hsu said that history writing “required an objective method” – distortions to fact arose due to external forces rather than questions intrinsic to history writing: “history was written in a subjective manner because historians were limited by their environment, and oppressed by institution and kings” and that “history as a new subject examines the truth of historical facts – even if it cannot become a science, its methods of study ought to be scientific”.32 For Hsu, the three schools of history were classical, scientific and metaphysical.33 Addressing a lay audience, Hsu made it clear that the task of history writing is the collection and verification of minutiae, and not their interpretation. It is no wonder that Hsu was more concerned about dispelling a rumour started by a French missionary in Thonburi – and seized upon by later rulers – that Taksin went “insane” and was unfit to govern because of his ascetic Buddhist practices; or as Luang Wichit tells it, Taksin’s downfall was caused by his two wives.34

The study of Taksin had already become an industry in China when Hsu’s translation of Luang Wichit’s text appeared in Shanghai in 1936. Besides Liang’s influential essay, Yi Benxi’s (pen name Xinhuang zhengyin) “Brief History of Overseas Chinese in the South Seas” (Nanyang huaqiao shilüe, 1910) gave a nationalist view of King Taksin and listed him as one of 11 accomplished “builders” overseas. In the late 1930s, the next generation of Taksin scholars such as Chen Yutai and Hsu Yun-Tsiao clarified the chronology of his reign, and more importantly, published their essays in the Nanyang, namely in Zhongyuan bao’s academic journal Zhongyuan Monthly (Zhongyuan yuekan) and its supplement Taiguo yanjiu. Remarkably, the latter publication was founded in September 1939, a few months after Siam became Thailand, and in the wake of Phibun’s crackdown on Chinese publications.

Japan’s invasion of China and the pro-Japanese and anti-Chinese sentiments that dominated in Thailand, compounded by the Kuomintang’s efforts to enlist overseas support for the war, immensely shaped Chinese research on Thailand and King Taksin. As I have shown, Hsu’s activism for overseas Chinese education was beholden to, and indeed scarred by, the post-1910 framework of Chinese racialisation during the reign of King Vajiravudh Rama VI. Dissatisfied with the annotations in his 1936 translation, Hsu published the essay “An Unofficial Biography of Taksin” (Zhengzhao waizhuan) two years later. Later essays include “A Study of China-Siam Historical Relations” (Zhong Xian tongshi kao, 1951), “A Study of Taksin’s Tribute to the Qing Court” (Zhengzhao rugong qingting kao, 1951) and “An Annotated Translation of a Poem Commemorating Taksin’s Tribute and Court Appearance in China” (Zhengzhao gongshi ruchao Zhongguo jixing shi yizhu, 1940), which was translated from Phraya Maha Nubhab’s account of Siam’s tribute to China in 1781.35

In 1936, Hsu’s appropriation of Siam’s nationalist histories for Chinese diasporic purposes predated revisionist writings of Thai history by historians affectionately known as the “Jek” (chink) school in the 1980s, once again calling attention to Chinese contributions to the Thai nationstate – not forgetting the Chinese bloodline of Siamese monarchs. In 1986, Nidhi Eoseewong published Thai Politics in the Reign of Thonburi, which challenged the “heroic life and tragic death of King Taksin” and has been since reprinted constantly.36 It is worth noting that after the founders of the Chakri dynasty (c. 1782) staged a palace coup against Taksin and executed him, Taksin’s legacy has been controversial and open to debate. The figure of Taksin has gone through waves of rehabilitation under both military and democratic rule. After the 1932 Siamese revolution, Taksin was used to “arouse nationalism, which subtly discredited the Chakri dynasty”.

In 1973, however, the People’s Party of 1932 was “presented as a representation of military rule who robbed the Thai people of a chance to gain a democratic constitution conferred by the King”. Royalism was strengthened via the figure of Taksin, where the “monarch’s traditional function as the epitome of ‘Thainess’ made it compulsory for all groups jostling for power to display their allegiance to the monarch”.37 In a further twist, as Sittithep Eaksittipong observes, while the figure of King Taksin helped to “writ[e] the Chinese into Thai history”, its use as a “seditious cultural symbol” to “subvert the sacredness of the Thai monarch as an abode of pure Thainess” instead “link[ed] the Chinese to the Thai monarchy”.38 This would cause trouble in academic debates about Chinese assimilation in Siam. Historian Wang Gungwu succinctly describes the controversy around what is known as the assimilation paradigm: “It was in this context that G. William Skinner wrote his two authoritative volumes on the Chinese in Thailand and stressed that the Chinese could, if the right policy were followed, be assimilated in Southeast Asia. Today, scholars tend to emphasise the degrees of political assimilation while pointing to the continued existence of Chinese ethnicity”.39 The paradoxical claim that the Chinese were never “the Other” but required inclusion into Thai society would become more perplexing in the “converging intellectual nationalism” of the Cold War period. From the mid-1970s, progressive Sino-Thai scholars protested against “American academic involvement with Thailand” by drawing on the work of nationalistic scholars from the People’s Republic of China who reasserted China’s claim to “long-term historical sovereignty over the Dai-inhabited areas of Yunnan”.40

Diasporic Nationalism and Hsu Yun-Tsiao’s Comparative Politics of China and Siam in 1933

In his diary from 1933, Hsu described the plight of the Chinese minority in Siam, and more generally, of the huaqiao (Chinese sojourners) in Southeast Asia. Responding, no doubt, to the front page of the newspaper, that space of simultaneity where, as Benedict Anderson argues,41 modern people find their place in the world, Hsu drew a parallel between the misfortunes of two minority peoples (the German Jews and Chinese in Siam) confronted with nationalist exclusivism:

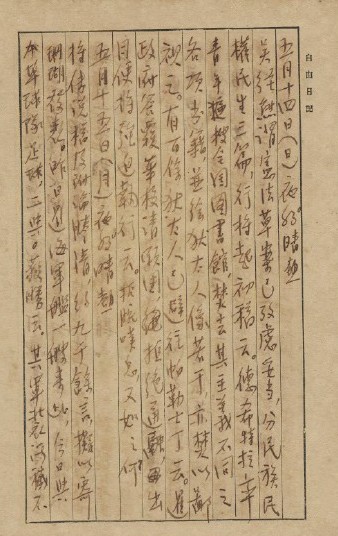

May 14 (sun) 83° at night, hot day

Wu Jingxiong said that the draft of the constitution has already

been considered reliable, and is divided into three sections, namely,

nationalism, democracy and the people’s livelihood, and will be

enacted based on this early draft. The Hitler Youth [youth wing of

the Nazi Party in Germany] ransacked all of Germany’s libraries

and burned all types of books that differed from their ideology. It

attached some kind of sign to the Jews, in order to permit them

to be burnt and loathed. Hundreds of Jews have already fled

to Palestine. The Siamese government responded to the Chinese

schools’ group petition, by rejecting an exemption from its rules. By

next month they will strongly enforce the law. All I can do is turn

up my palms and lament. I don’t know what to do. (p. 132)

五月十四日(日)夜83°晴热

吴经熊谓宪法草案已考虑妥当,分民族民权民生三篇,行将起初稿云。德

希特拉 卒青年遍搜全国图书馆,焚去其主义不同之各项书籍,并绘犹太

人像若干,亦焚以鄙视之。有百馀犹太人已避往帕勒士丁云。暹政府答覆

华校请愿团, 拒绝通融,出月便将强迫执行云。扼腕叹息,不知之何?

It is clear that Hsu felt sympathy for the plight of the German Jews, whose troubles were just beginning, and anxiety about the status of his own minority group, the Chinese in Siam, who confronted demands for cultural and linguistic assimilation in ways that particularly concerned him as an educator.42

Against this backdrop, Hsu invoked Chinese law. The inconclusive debates over democracy and dictatorship in China during the 1920s resulted in the failure to implement a liberal constitution.43 Finally, in 1933, the Americantrained lawyer Wu Jingxiong (John Ching Hsiung Wu) drafted the first version of China’s 1946 constitution, known as the Wu draft. Article 1 of the draft stated that the Republic of China was a san-min chu-i [sanmin zhuyi] Republic, or a republic based on Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People, namely, “nationalism, democracy and the people’s livelihood”.44 Though promising to replace the nominal constitution accepted by the Beiyang generals, or warlords, after their defeat by the Kuomintang army during the Northern Expedition (1926–28), the Wu draft downplayed two cornerstones of Kuomintang policy in earlier times – Sun Yat-sen’s emphasis on the international anti-imperialist struggle and the liberal notion of individual rights. It framed the struggle for freedom in terms of an essential “Chinese” legacy of national salvation, whereby the party-state was now legally authorised to crush Leftist dissent from its leader Chiang Kai-shek’s “revolutionary nativism”.45

Hsu does not discuss such ideological overtones in Wu’s 1933 draft constitution. What concerns Hsu, as the extract shows, is whether its rule of law and political interpretation apply to “overseas Chinese” subjects in Siam. Whereas citizens in China might have been concerned that the 1933 draft gave the state too much power over them as individuals, it is conceivable that a diasporic person like Hsu would want to see state power maximised because only then could China intervene in the affairs of countries where Chinese sojourners lived. Hsu lamented that China was not doing enough and worried about the lack of wartime rights advocacy for minority subjects with no backup from a powerful state (again, a situation where Jews and Chinese were not precisely in the same plight).46 The dilemma of the Kuomintang government’s right and ability to extend its protection over “overseas Chinese” populations would be resolved in the succeeding People’s Republic of China premier Zhou Enlai’s 1955 speech at the Afro- Asian conference in Bandung, where the overseas Chinese were asked to become citizens of either China or the decolonising nation-state where they were based.47 Today, this subtext is downplayed against the background of Chinese military expansion into Philippine and Vietnamese coastal areas, which I will discuss later.

Zhou’s Bandung speech assumed that the citizenship question could be clearly defined in an emerging world of no longer colonial nation-states, each defined by their predominant ethnicity. Diasporic populations would no longer suffer second-class citizenship; their loyalty would no longer be suspect, but could be unambiguously declared for one nation or another. However, the history of the Chinese diaspora in the South Seas is somewhat more complex than an either/or option would allow. For one thing, powerful figures among the host nations persisted in justifying discrimination against Chinese sojourners. The best-known expression of this policy is the essay “The Jews of the Orient” (1914) written by King Vajiravudh Rama VI (r. 1910–25) under the pen name of Asavabahu.48

The Jewish-Chinese comparison first given broad circulation in that essay normalised, or at very least, symptomatised the racialisation of the Chinese as Other in the allegedly ethnic Thai nation. Chinese “racial loyalty”, so goes Asavabahu’s accusation, made them “undesirable immigrants”, because they felt entitled to “expect to enjoy all the privileges of citizens without assuming any of the obligations” such as the corvée labour requirement for natives, and their expectation involved an “unstable allegiance” to material benefits such as tax evasion and social services – they “suspended work” to “protest having to pay THE SAME POLL TAX THAT ALL THAI PAY” and would ironically deign to register themselves as “nationals of foreign countries, even within China itself”.49

The 1914 essay thus posed the question of Chinese extraterritorial rights in Siam, variously described as a semi-colonial, semi-feudal and cryptocolonial social formation whose monarchs retained independence from directly exercised Western imperialism but reproduced its governing structures within.50 For another thing, successive Chinese governments (and opposition parties) often depended on the support of émigré communities, who by their wealth and standing wielded outsized influence. Many have since parsed King Vajiravudh’s racist screed as a complex political and social response to changing times – and therefore not to be taken at face value. The king was aware of the power of diaspora communities; the fall of the Manchu dynasty in 1912 and the influence of republican ideology from China made him fearful of a spillover from a revolution against the monarchy. Hsu supplies evidence to support this view in Beidanian shi (History of Patani, 1946); indeed, the nationalist anti-Qing, or Patriotic Movement (aiguo yundong), had spread as far south as Patani.51

Two other local incidents were probably at the back of the king’s mind: the three-day strike to protest the increase of the head tax, as mentioned, and the failed uprising or Palace Revolt of 1912 against him by young military officers, some of whom were Sino-Thai. To these political motives may be added an economic one. It is worth noting that, prior to the surge of Chinese immigration to Siam in 1918, Vajiravudh had described only the recently arrived poor, rural Chinese as “bad”, and criticised them for being stubbornly resistant to assimilation, because they refused to become Thai by failing to adopt his official nationalism of language, culture and service to the king.52 He had “ignor[ed] the Chinese who had been absorbed into the bureaucracy and old merchant families that had close business and personal ties to the monarchy”.53 Thus, the ethnic libel was perhaps no more than a fig leaf. Given such success in middle- and upper-class Thai-Chinese assimilation before the 20th century, Wasana Wongsurawat argues that the “Jewish analogy has acted as a sort of red herring, distracting observers from better explanations as to why the roles of China and the ethnic Chinese in the favorable outcome of the Second World War for Thailand have been so successfully expunged”.54 Instead of state-driven, anti-Chinese discriminatory policies and propaganda, Wongsurawat views anticommunist international relations as a more satisfactory reason for the forgotten history of the left-leaning revolutionary Chinese participation in the Allied-supporting Free Thai Movement, which opposed the Japanese-Thai alliance and saved Thailand from being defeated (i.e. from being on the wrong side) in the war. In hindsight, “Vajiravudh’s railing against the Chinese did not result in a purge or genocide (as suffered by the Jews in Europe) but led to political policies that began the process of forcing the Chinese to assimilate into Thai society”.55

But Hsu could not have possibly anticipated this outcome when he mentioned King Vajiravudh’s essay in another diary entry. He took antiassimilation Chinese education policies in Siam as his baseline, using an erudite instance of late-Qing political relations to disambiguate the Jewish- Chinese comparison:

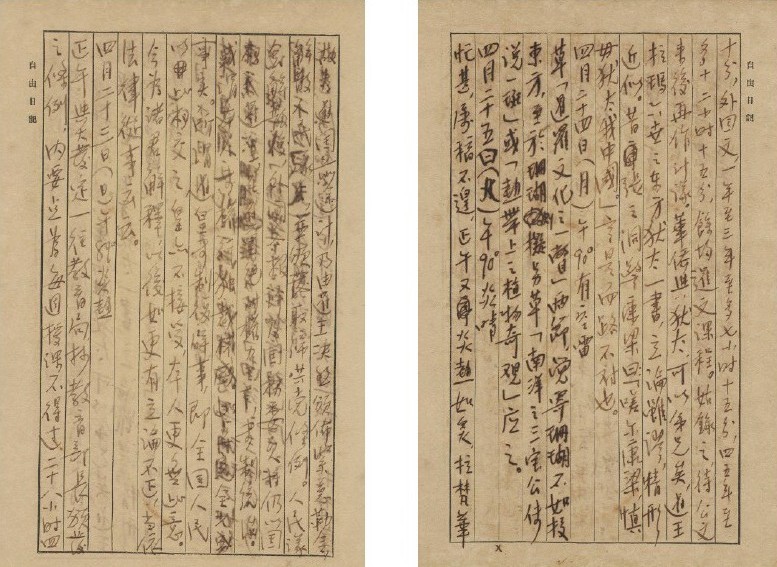

April 23 (sun) 89° in the afternoon, hot

At noon, I went with Da Fa and Ding Yi to the Education

Bureau to copy out the laws issued by the Minister of Education.

The important points include: each week classes cannot exceed 28

hours and 40 minutes, for foreign languages, first to third years can

have a maximum of 7 hours and 15 minutes, fourth to fifth years a

maximum of 12 hours and 15 minutes, the remaining hours are for

Thai language classes. Tentatively we wrote them down, but will

wait for the official document to make plans. The overseas Chinese

and Jews are comparable. Although the arguments in King Rama

VI’s essay, “The Jews of the Orient”, were ridiculous, the situations

are similar. In the past Zhang Zhidong warned Kang Youwei

and Liang Qichao: “Ah, Kang and Liang, be careful not to make

China Jewish”. He named the problem correctly but the way out

isn’t clear. (pp. 119-120)

(Right) 23 April 1933 entry in Hsu Yun-Tsiao’s diary (v. 2: p. 120; Accession no. B27705372K). Hsu Yun Tsiao collection, National Library, Singapore.

四月二十三日(日)午89°炎热

正午与大发定一往教育局抄教育部长颁发之条例,内要点为每周授课不

得过二十八小时四十分,外国文,一年至三年至多七小时十五分,四五

年至多十二小时十五分,余均暹文课程。姑录之,待公文来后再作计

谋。华侨与犹太可以弟兄矣,暹王拉玛六世之东方犹太一书,立论虽

谬,情形近似。昔张之洞警康梁曰:[嗟尔康梁,慎毋犹太我中国]。

言是而路不衬也。

Hsu compares older and newer (dixiong) cases of the predicament of an economically dominant minority with no state to back them up in the context of late-Qing governance. In 1900, Zhang Zhidong, the governor-general of Hunan and Hubei provinces, with the backing of the Emperor Dowager Cixi, crushed the Hunanese revolt led by Tang Caichang’s Independence Army (zili jun).56 Incidentally, the Independence Army Uprising received the financial support of the baohuang hui (Restoration Party), founded by Kang Youwei and his reform-minded students such as Liang Qichao after their escape to Tokyo following the failed Hundred Days’ Reform (wuxu bianfa) of 1898.57 In his 23 April 1933 diary entry, Hsu cites the end of Zhang Zhidong’s written proclamation, “Exhorting the Shanghai Congress and Students Abroad” (quanjie Shanghai guohui ji chuyang xuesheng wen), which blamed the uprising on the Kang clique and asserted the Qing’s support for overseas Chinese students in Japan and elsewhere like Southeast Asia.58 It is worth mentioning that only recently had “huaqiao” become a prestigious group relied upon for domestic political and financial needs after its denigration during China’s long history of banning outward migration and private maritime trade.59 When Zhang admonishes, “Ah, Kang and Liang, be careful not to make China Jewish”, it is unclear if he was cautioning against making the diaspora dominant in Chinese affairs, or identifying the Chinese with their diaspora, or even emptying out China through outward migration. Either way, he suggests that the Qing was capable of governing an actual nation-state, which the Jews lacked, and should not suffer the reformists’ campaign as far as Canada, Hawaii, Japan and the U.S. to portray “China’s plight as a nation too weak and backward to protect its emigrants from discrimination abroad”.60

Arguing that Kang Youwei’s reformist reading of the Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu) to address the Qing political crises was wrong, Zhang Zhidong seems to claim that the present order under the Qing was the only possible one if China was to avoid breaking up and colonisation.61 Of course, there is some irony in the fact that an ethnic minority was ruling China at the time and that much of the resentment against Qing rule was cast as a quasi-democratic revolt of the Han majority.62 This majority/minority dynamic certainly complicates the use of the label “Jew”. Zhang’s speech was part of his harried attempt to re-establish diplomatic relations, via Chinese embassies in Britain and Japan, with foreign nations of the Eight Nation Alliance, in the wake of the Qing’s ill-fated support of the anti-foreign, anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901).63 Thirty years later, for Hsu to frame the perils of Chinese diaspora in terms of China’s eroded international standing due to domestic revolts against the Qing and imperial nations, and specifically, via pro-and anti-Empress Dowager factions in the history of Chinese political reform, suggests Hsu’s desire for a leadership that still extended its care for huaqiao despite domestic unrest. Hsu lamented the absence of such leadership during the “Nanjing decade” of Kuomintang rule (1928–37), when the government was severely weakened by invading Japanese armies, which bombed his hometown Suzhou during the 1932 Shanghai incident.

The League of Nations and the Mukden Incident

During China’s War of Resistance against Japan (Zhongguo kang Ri zhanzheng, 1931–45), Hsu was right to be less than optimistic about the League of Nations’s due process in guaranteeing Chinese national sovereignty at Geneva. The Japanese seizure of Manchuria (1931–32), or the Mukden Incident, followed by the invasion of Shanghai (1932) and the Treaty of Tanggu (1933), where “Chiang was forced to abandon any armed resistance against the establishment of Japanese-controlled Manchukuo to the north”, were presented by Japanese imperial propaganda as necessary measures to liberate the Manchurians from the oppressive Chinese warlord regimes of Zhang Zuolin (1916–28) and his son Zhang Xueliang (1928–31).64 “Even foreign observers in China mockingly commented on China’s attempts to appeal to Geneva for help”.65 Hsu’s diary entry on the Kwantung Army’s capture of Shanhaiguan Pass at the Great Wall on 3 January 1933, which ended in the inner Mongolian province Rehe’s annexation to Manchukuo two months later, echoes this sentiment:

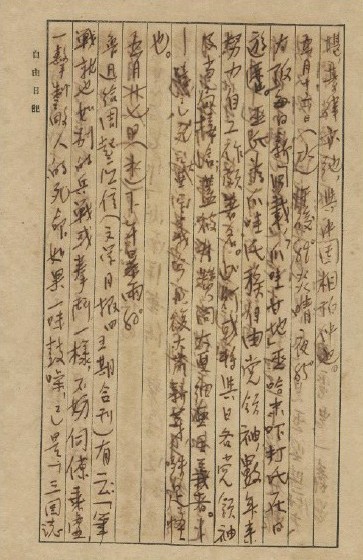

January 5 (water) sunny, 85° in the afternoon

A dispatch arrived: on New Year’s night, the Japanese military

launched a fierce attack on the Shanhaiguan Pass, shocking North

China, which was lost today. Some London newspaper criticised

Zhang Xueliang’s policy of non-resistance and waiting for the

League of Nations as wishful thinking and self-deception. (p. 11)

一月五日(水)晴,午85°

电讯传来:日军于元旦夜猛攻山海关,华北震动,今且失守焉。伦敦某

报批评张学良之不抵抗待国联之迷梦,将成画饼。

International opinion unexpectedly swung in China’s favour. Based on the 1932 Lytton Commission report that recommended “shared sovereignty over Manchuria”, China’s newly minted Minister to France, Wellington Koo, presented China’s case at Geneva and successfully argued that Manchukuo was “an unequivocal violation of China’s national sovereignty”.66 As a result of Koo’s appeal to multilateral diplomacy and international law to resolve the crisis, the League of Nations, in a special assembly on 25 February 1933, voted nearly unanimously not to recognise Manchukuo, with only Siam abstaining. The Japanese delegation promptly withdrew from the League of Nations. China had successfully, though nominally, defended against Japanese aggression, but Hsu saw Siam’s “vote” and increasing collaboration with Japan as a worrying development for the “overseas Chinese” in Siam.

Indeed, the League of Nations had a dismal record on the issue of minority rights: in 1928, it upheld “the principle of national sovereignty in response to petitions about racial discrimination”67; and in 1925, 1930 and 1932, it “rejected proposals to obligate all members to guarantee the rights of minorities”. Hsu further connected Geneva’s unsettling failure to resolve the Mukden Incident with the counter-revolutionary aftershocks of the 1932 Siamese Revolution, which sought to consolidate Siam according to modern ethnic notions of the nation-state:

February 27 (moon) 89° in the afternoon, 83° at night

A newspaper report: The [Special Assembly of the] League of

Nations Report of 19-Nations was resolutely passed, yet Siam

abstained from voting, and as a result, the Japanese applauded and

rewarded them. In the afternoon, Nantong came to chat, and said

that the Siamese king has already retreated to Hua Hin, and the

North might be rebelling soon. At first I couldn’t believe it, but then

I saw that a Penang newspaper received such a telegram, though the

Siamese government denied this. On the one hand, Siam suppresses

the overseas Chinese, and on the other hand, ingratiates itself with

the Japanese, I really fear this will be my misfortune soon! Nantong

said: there are papers to sign in Thai when I get married. Hsu was

getting married to Jingmei, but because of the bombing of Suzhou,

they could not celebrate. (p. 66).68

二月二十七日(月)午后89°夜83°

报载:国联十九国报告书__决通过,但暹代表不举手,后日人大加赞

赏。午后南通来谈,云暹王已避居华兴,北部或将叛乱。余初不信,

然见槟城报纸尔有是项电信,但暹政府否认耳。暹一方压迫华侨,一方

面取媚日人,诚恐将来为其本身之祸根耳!南通云:办姑娘事,暹文有

书云。

An examination of Hsu’s diaries reveals that his interwar Nanyang studies can be understood as part of a transnational scholarly effort to comprehend the rapidly evolving global framework of human rights (especially minority rights of the “diasporic”), the implementation of constitutional law in Siam and China, and multilateral diplomacy’s guarantee of national sovereignty – emerging norms of law and custom that met with varying degrees of success during the rise of fascist militarism in the 1930s.

In Hsu’s 27 February 1933 diary entry, the news of King Prajadhipok Rama VII’s retreat to Hua Hin and that “the North might be rebelling soon” were mediated via a telegram sent to a Penang newspaper in the Straits Settlements. The exceptional feature of Hsu’s 1933 diary – the longest of the five volumes at 400 pages, written in classical Chinese and sometimes illegible handwriting – is its vast expression of “lifewriting” by an aspiring historian who also wrote literature (e.g. classical-style poems), interpreted historical events through the lens of literary history, and pioneered the genre of Nanyang “anecdotal histories” (shihua), which he later popularised through brief radio lectures and extracurricular “textbooks” on Nanyang histories in postwar Singapore.69 To overcome the belatedness or perceived deficiency of his “diasporic time”, Hsu mixes historical and anachronistic registers to make sense of his transient residence in Pattani in 1933, and in doing so, updates the Chinese tradition of diary keeping.70

The Paracel Islands Dispute

May 16 (fire) 83° at night, hot day

Each day Osaka publishes news about the “Javanese Gandhi”,

Mohammad Hatta’s, travels in Japan. Hatta is the leader of

the independence party for the Javanese; for many years he has

worked hard for the struggle and gained fame. On this trip

maybe he is getting in touch with various leaders and other

parties in Japan; he definitely supports Greater Asia. Today the

ideology of Greater Asia that was dead has a new lease on life.

Remarkable indeed (p. 133).

五月十六日(火)午后89°炎晴夜85°

大阪每日开载[爪哇甘地]巫哈末吓打氏在日,游历。巫氏为爪哇氏族

自由党领袖,数年来努力自工作颇著名。此行或将与日各党领袖及当局

接洽;蓋彼为赞同大亚细亚主义者。已死之大亚主义今日復大萌新芽

殊足怪也。

Pan-Asianism, according to Okakura Tenshin and others later inspired by Russia’s defeat by Japan (1905) such as Sun Yat-sen and Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, proposed a united Asia to fight European imperialism. Incidentally, Hsu’s first publication, a chapbook of poems, Fu Yun (Floating Clouds) was written in imitation of Zheng Zhenduo’s 1922 translation of Tagore’s Stray Birds (Feiniao ji, 1916).71 In 1933, Hsu was presciently skeptical of Japan’s leadership of a Greater Asia. Given a “new lease on life”, this form of pan-Asianism would soon become Japan’s rationale for military aggression for a Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. So when the nationalist leader Mohammad Hatta – later Indonesia’s first vice-president under Sukarno following Japan’s surrender in 1945 – wooed Japan’s support for Dutch East Indies independence, Hsu does not say much about this dubious partnership. Instead, he focused on what for him represented a clear case of anti-imperial consciousness: a challenge to China’s sovereignty in the South China Sea by French Indochina in the Paracel Islands dispute.

As in the Manchukuo incident, then as now, China based its claims over island chains such as the Paracels (Xisha or western sands) and Spratlys (Nansha or southern sands) on historic right.72 Even before the Sino-French war (1884–85), when the Qing conceded Annam and Tonkin (Vietnam) to the French, who then consolidated their presence in the region, the Paracels had a long, complex diplomatic history of expedition and settlement that involved Chinese fishermen and cartographers, British merchants, German missionaries and French custom officials and scientists. Japanese economic interests, or “indulgence” according to Hsu’s citation of a Soviet newspaper, took the form of ocean phosphate mining by Mitsui Bussan Kaisha since the 1920s. French occupation of this so-called terra nullius was gradual at first. Its government formally claimed and annexed the Paracels to Annam in 1932, and the Spratlys to Cochinchina in 1933, which set off modern sovereignty claims by Japan, Vietnam, China, as well as Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Philippines, which continue to this day.73

Hsu followed the Paracels dispute closely in his 1933 diary, and published an essay, “The Disgraceful History of Pattle (Shanhu) Island”, in the biweekly Suzhou-based magazine, Shanhu (1932–34), co-founded by Fan Yanqiao after the Mukden Incident.74 In an earlier issue, Hsu had published “The Myth of San Bao Gong (Zheng He) in Southeast Asia”, a topic on which he expanded.75 These two early examples of Hsu’s Nanyang studies responded to the threat to China’s maritime sovereignty. But during this bitter commotion, Hsu made room for more positive news. For instance, he notes Siam’s prize-winning display of modernity at the World’s Grain Conference and Exhibition in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada (24 July–5 August 1933); a twist concerning textbooks in the saga of Chinese school activism; the constant stream of fundraising activities besides his teaching duties; his role as a jack-ofall- trades for the Chinese community in literary matters (though he did not always think highly of his workmanship); the cost of clothes alteration at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula; as well as including, as usual, a snippet of news that showed the perils of strongman politics and brinkmanship:

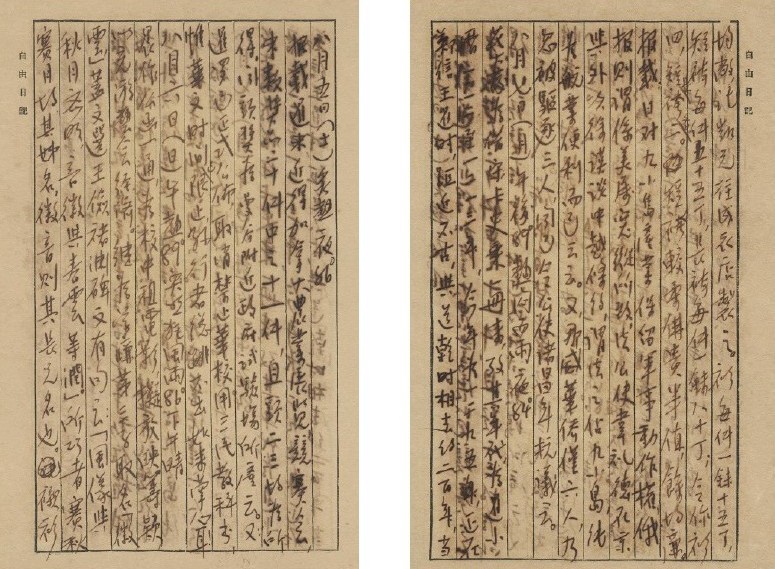

August 5 (earth) scorching hot, 86° at night

A newspaper report: Siam recently participated in Canada’s

Agricultural Exhibition and Competition and won 11 out of the

20 prizes, as well as the the top two or three prizes for its rice.

I heard that the top prize was won by the display by Bangkok’s

nearby government experimental factory. Siam already formally

announced that it would cancel its ban on Chinese schools using

the textbooks based on the Three People’s Principles (sanmin).

Only Chinese language hours will be limited. It’s like the Monkey

King unable to escape Buddha’s palm!76

August 6 (sun) 89° in the afternoon, hot, suddenly a typhoon,

86° in the afternoon, sunny

In the morning I wrote a formal document requesting to rent

film equipment for our school. We plan to screen a movie to raise

funds to benefit the traveling artist troupe. Next, I came up with a

name for Xuelian’s third son: Hui Yun. It comes from Wang Jian’s

“Memorial Inscription for Chu Yuan” in Selections of Refined

Literature (Wen Xuan). “One’s style and demeanor as bright as

the autumn moon, one’s sentiments and morality as full-bodied

as a spring cloud”. Sai Qiu and Sai Yue are the younger sisters’

names, and Hui Yin is the name of the eldest son [so Hui Yun is

an appropriate extension of the pattern, through the allusion to

“autumn” (qiu) and “moon” (yue)]. My shirt is too big, so I asked

Kai Yuan to have it altered at the tailor’s. Each shirt costs one

baht and 15 satang, and each pair of shorts costs 55 satang, long

pants are more expensive by half compared to Johor prices, the rest

are cheaper. A newspaper report: Japan maintained its claim of

military right over the nine islands where it has industries, a Soviet

newspaper claims that its presence there is caused by appeasement.

The French Legation officer in Beijing, [Henry August] Wilden,

_times schemed and talked about the China-Vietnam treaty, and

said that the French occupied the nine small islands, and that

boundaries should be drawn to suit the convenience of shipping

trade. I heard that Zhua Changnian [Tang Shaoyi’s son-in-law]

protested against the intimidation of Chinese sojourners and the

deportation of three Chinese. (pp. 205–206)

八月五日(土)炙热夜86°

报载暹米近得加拿大农业展览竞赛会,米谷奖只二十件中之十一件,且

头二三均为所得,闻头奖为曼谷附近政府试验场所产云。又暹罗已正式

公布,取消禁止华校用三民教科书,惟华文时间已限止,孙行者总跳不

出如来掌心耳!

八月六日(日)午热89°突然狂风雨86°下午晴

晨作么出一通,为校中租电影,拟放映筹欵以充游艺会经济。继为学廉

茅三子取名[徽云]蓋文选王俭褚渊碑文有句云:[风仪与秋月齐明,

音徽与春云等润]。所__者赛秋赛月均(?)其妹名,徽音则其长之名也。

衬衫均敞,讬凯元往成衣店制之。衫每件一铢十五丁,短裤每件五十五

丁,长裤较柔佛贵半值,余均廉。报载:日对九小岛产业保留军事动

作权,俄报则谓係美居宽纵所致,法公使韦礼德在京__外次余谟谈中越

条约,谓法之佔九小岛,线为航业便利而已云云。又那威华侨仅六人,

乃忽被驱逐三人,闻已令公使诸昌年抗议云。

(Right) 6 August 1933 entry in Hsu Yun-Tsiao’s diary (v. 2: p. 206, Accession no.: B27705372K). Hsu Yun Tsiao collection, National Library, Singapore.

The layers of politics and erudition in Hsu’s diary evoke “a thick transregionalism, a spatially expansive yet integrative account of a mobile society”.77 Hsu’s diary urgently shapes and consolidates his public response to the evolving relationship between Siam and China, and interwar modernity. In the next section, I will consider how the genre of the diary allows older ideas of diasporic nationalism to converge with Hsu’s “minorpeninsular” poetics of discovering Malay-Muslim Patani through textual histories and of observing the Bowaradej (royalist) rebellion from afar.

Hsu’s Minor-Peninsular Patani: Literature, Politics and Religion

Prince Damrong’s histories, which Hsu admired, said that Patani “belonged to the Thai [kingdom] since time immemorial [… which] presumably refers to the Sukhothai kingdom, the first recognised “Thai” kingdom”.78 But Patani was an autonomous territory before it was colonised by Bangkok: “the 1909 Anglo-Siamese treaty marked the formal transfer of authority to Bangkok in return for the abandoning of Siamese claims to Kedah, Kelantan, and the Malay states further south”.79 In the 1930s, the encroachment of the Thai imperial project, which combined Theravada Buddhism with “European forms of institutional and legal modernity” affected Siam’s large Chinese minority but left Jawi-speaking Malay- Muslims in its southern provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat relatively untouched.80 Islamic law on polygamy and inheritance, for example, was administered as private law so that Malay-Muslims could become Thai subjects and citizens. A few years later they became the targets for assimilation in cultural, linguistic, education and legal terms.

In a move to decolonise historical methods and write local, autonomous histories from new angles, such as examining port-city connections, while acknowledging the importance of Chinese sources, new scholarship also addresses the recent spate of ethno-religious violence in the region. Anthony Reid has described the Thai South and Malay North as a “plural peninsula”, whose “polycultural” nature meant that differences ought to be explained by “specific historical dynamics rather than superficial ethnic distinctions”.81 Since the 16th century, the cosmopolitan Patani has been “the kind of base for the Chinese Southeast Asian trade that Bangkok, Batavia and Singapore later became, with its ships sailing throughout the Archipelago as far as Makassar, and to Ayuthaya and Hoi An”.82 In fact, the “importance of Patani for the Chinese trade in the early 17th century made the Kedah- Patani portage also attractive as a journey of about 10 days”.83 Sojourning a few centuries later, the Suzhou-born historian Hsu was sensitive to this as he taught in Patani and witnessed Siam’s tumultuous constitutional struggle and ethnonationalist shaping of the nation. As Hsu reconstructed Patani’s cultural pluralism through Thai, Burmese, Malay and Chinese sources, he filtered it through the lens of diasporic nationalism, that is, his homeland’s civilisational mission of overseas Chinese education and wartime mobilisation effort against the Japanese. Patani indigeneity, as such, emerges through Hsu’s obsessive archival work of textual histories rather than an observation of present-day local customs.84

This counter-temporal layer of politics and erudition in Hsu’s diary is “plural”, but not in Reid’s sense. I choose the term “minor-peninsular” to evoke Hsu’s Patani, whose “thick transregionalism, a spatially expansive yet integrative account of a mobile society”, functions according to diasporic scales and agencies.85 Hence, Hsu’s tracing of Chinese migrant knowledge and sojourner activism understands local Patani histories in a triangulated way. In his short story “The Young Navigator” (1946), Hsu reconstructs the trauma of Chinese diaspora in the Asia-Pacific war through the eyes of a small boy who flees by boat from Selat (Singapore) through Songkhla, Kuantan, Kelantan and Terengganu, hiding at their “peninsular ports” that escaped the reach of empires.86 Hsu even used Hokkien phrases such as* jiu baxing, a reference to an important river transport hub in Fuzhou, China whose complex system involved pricing goods for foreign customers at 98 percent. Fusing the “heroic figures” of Robinson Crusoe and the famous Ming admiral and Muslim eunuch Zheng He’s voyages with Malay *merantau (wandering) culture, Hsu’s survivor’s tale has a naïve, ethnographic realism that grounds the adventurous child’s perseverance in the militarised war economy. Hsu wrote another story about Japanese-occupied Singapore, narrated through the eyes of a baby chicken.87

Indeed, Hsu’s creative work relied heavily on his research on maritime circulations. After leaving Siam in 1938, Hsu continued his Thai studies in Singapore. He published the short story “Dufu” (Ferryman) by Thai female social realist writer K. Surangkhanang (given name Kanha Kiangsiri, 1911– 99), translated into Mandarin by Ye Yi, in the journal he edited, Nanyang Miscellany (Nanyang zazhi, 1948).88 Volume 1:4 (1946) contained short essays about Patani and Thai customs, as well as a travel account of Malaya and Thailand (“Ma Xian jixing”), making it easy to conclude that Hsu saw southern Thailand as continuous with the Malay peninsula. In a short paragraph titled “The Historical Status of Patani” from his anecdotal history “The Development of States on the East Coast”, Hsu notes:

“Dani” or “Danian” is short for Patani [in Chinese sources].

Though not included in Malaya’s histories, Patani had a

very close relationship with the Malayan states, and is also on

the Malay peninsula. Patani was the most powerful Malay

kingdom after the Malacca Sultanate fell, and, before Singapore

flourished, the state was most prosperous during the reign of the

Patani queens between 1588 and 1627, when overseas Chinese and

Anglo-Dutch traders would go there to conduct business. At this

time, Johor’s state presence was far less than Patani’s. The reign

of the queens was methodical. They had a close relationship with

Johor and Pahang, but also used military strength [to fight off

Siamese invasions].*89

Defined neither by capital flows between Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore, nor the mainland writer’s exotic desire for the tropics during exile, Hsu’s Nanyang imagination lay in its historical geography and sea routes used by traders and “pirates”, and occasionally, the orphan child. Focused on the high seas, Hsu’s history-writing inverts what Wang Gungwu calls an “earthbound continental” mindset, or the neo-Confucian ideology of agrarian dedication, that dominates imperial histories, oriented along a North-central axis, and the genealogies of southern elite families alike.90 In his diary, Hsu fixates on the story of the Teochew pirate (wokou) Lin Daoqian, who attacked the coasts of Fujian and Guangdong when private trade with foreign merchants was outlawed during the Ming, and escaped to Kaohsiung, Champa, Luzon, and finally, Patani (c. 1566). There Lin settled with his 2,000 Cantonese followers, rose to prominence, obtained a fief by serving the sultan and marrying his daughter and, according to a local legend, built the Krue Se (Gresik) Mosque and died a Muslim. The bronze cannon he had cast had blasted him: “one cannon would not go off, so Lin went to fix it and it hurled him into the ocean… The other cannon is still stored in the Bangkok palace” [v. 2: 158–59] and is “named พระยาตานี [phraya tani]” [v. 2: 207].

Buried next to Lin at the mosque is Lim Ko Niao (Lim Guniang), or his alleged sister, who pursued him from China and “committed suicide by hanging herself from a tree after protesting in vain” against her brother’s conversion. As Reid notes, “[t]his lady’s cult was already known locally in the late 19th century, but in the nationalist 20th century, she (the upholder of pure ‘Chinese’ tradition), rather than the peranakan Lin Daoqian (the founder of local Chinese identity and fortune), became a hero for the Chinese of Singapore and Malaysia”. Hsu describes in detail in his diary a festivity at Lim Ko Niao’s shrine in Pattani, and thus gives a hint of why it appeals to today’s “cross-border religious tourism” and its view that southern Thailand is “a substitute Chinese homeland”.91

In October 1933, Hsu finished his essay, “A Study of Lin Daoqian’s Brief Time in Patani”, and had it published in Dongfang zazhi in January 1935 (Vol. 32) [v. 2: 282].92 He was proud to correct the mistake in Chinese annals that mixed up Brunei (boni) with Pattani (dani). In his later History of Patani, Hsu examined Patani’s port-city connections to southern China, Japan, as well as Portuguese traders during the age of commerce (1450– 1680). He also included an appendix of biographies about nine Chinese traders or “pirates” who ended up in Patani, such as the aforementioned Lin Daoqian and Wang Dayuan.93 A counterpoint to the magisterial histories of Zheng He’s expeditions, Hsu’s biographies of swashbuckling seafarers recall Liang Qichao’s eight settler colonialists, but also pioneered the local history of Chinese in Patani.

Hsu’s Account of the Bowaradej (Royalist) Rebellion in October 1933

It seems perplexing that Hsu draws on textual histories and world reports on Jewish diaspora, rather than materials relating to the Patani Malay- Muslims in front of him, to establish his diasporic subjectivity and response to the erosion of Chinese rights in Siam. From his diaries, it seems that international news stimulated his reflections on Nanyang affairs. A history that is merely local does not have consequences; a history that resembles other histories gains importance. Hsu’s elision of Patani’s modern populace indicates that he was mainly concerned with Chinese minority populations, and not with minority populations as such. As Sharon Carstens notes, Hsu’s foreword to the first issue of Journal of the South Seas (1940) “laid out the goals of the publication, chief among which was a desire to utilise Chinese culture and scholarship to increase respect for the overseas Chinese, who were too often characterised as the ‘Jews of the Orient’”.94 Hsu’s minor-peninsular Patani emerges most vividly in his detailed accounts of the Bowaradej (royalist) rebellion of October 1933. After the unsuccessful coup d’état of 20 June 1933, Prince Bowaradej (1877–1947), financed by King Prajadhipok, who had retreated to Hua Hin and later Songkhla [v. 2: 66, 268, 277], led a revolt against Khana Ratsadon’s constitutional regime, following the Siamese Revolution of 1932. Hsu records with alarm that “rebels” had occupied the Don Muang airport on 12 October, and the transport lines that were cut by the resulting chaos:

October 18 (water) sunny and hot, 83° at night

The chaos in Siam affected traffic. The mail coach from the Malay

Federation can only reach Prachin Buri province, which should

now be under occupation by the rebel troops. Apparently, the troops

at the Don Muang rebel base number 5,000 to 10,000, and are

engaged in extremely violent battle with the capital. The telegram

lines have been cut, the situation is serious, the government’s

declaration to subdue the rebel groups within two days is not

tenable. Today I translated The History of Pattani Province, and

omitted half of it. [p. 269]

十月十八日(水)晴热夜83°

暹罗变乱,影响交通,马来联邦邮车祗能通至巴真武里,应该处已为叛

军所占据。据云叛军根据地在Don Muang 为数自五千至一万,其在京畿

开火者,颇为猛烈云。电线均已隔断,形势严重,政府之宣言能克服之

于二日内者,不可持矣。今日译大泥府志,去其半矣。

Observing the chaos from afar, Hsu engaged in his translation of Pattani and Songkhla histories; completed his essay on Lin Daoqian; wrote about a power struggle in the principal ranks of a newly formed Bangkok Chinese high school; and gave an anecdotal history of the origins of Deepavali (the Hindu festival of lights). In this heady mix of contexts, Hsu’s sympathy for Patani sovereignty appears for the first time; the Bowaradej revolt, for Hsu, also led to the consolidation of southern Thailand under Siamese rule:

Other parts of Thailand were mostly conservative, should the

rebel army reach them, they will not be independent (from the

monarchy). In Patani, which is in the South, there are Siamese

who became officials to consolidate the mostly Malay region under

the new regime. In Songkhla, … the Siamese army stationed and

set up camp at the English- and European-owned mines. Also, Sing

Sian (newspaper?) jointly pronounced that the rebel army has been

vanquished, and King Rama VI fled by plane. Who to believe?

其他各地大多保守觉,一旦被叛军勾通,不难独立也。至南方大年则

有暹罗人为长官,统揽政权,惟人口多巫族。宋卡,布吉,多邪 (?) 等

地,暹军驻扎处,均英澳人投资矿产所也。又据星暹统称,叛军已溃,

亲王乘机出奔。不知信否。

Conclusion: The Significance of Hsu’s Diaries to Nanyang Historiography

Seen less charitably, Hsu’s interwar Nanyang studies was a partisan reflection of the Chinese war mobilisation effort. Just as “disciplined diary writing” was introduced “as late as the ‘Nanjing decade’ of GMD [Kuomintang] rule” to shape soldiers’ commitment to acts of violence, Hsu’s diary helped him, as a historian, be accountable to the Chinese nationalist cause and hence not to be considered a “collaborationist” or “Chinese traitor” (hanjian). Writing the self mobilised his convictions and transformed his consciousness to act in his own ways while being far away from his hometown of Suzhou, China. Hsu’s personal diary recalls the prized genre of loyalist resistance and moral self-reflection by late-Ming literati opposing the traumatic Qing transition.95 Perhaps after the 1930s the reason for diary-writing faded. After Hsu moved to Singapore in 1938, his collaboration with “southbound intellectuals” (nanlai wenren) to research and publish works through the South Seas Society was interrupted by the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), which forced him into hiding. Diary keeping, if discovered, could have meant death; even his History of Patani (1946) manuscript, completed in 1940, had to be stashed in the ceiling board, and was thankfully only half-eaten by silverfish. Instead of private life-writing, Hsu found similar genres such as children’s literature, anecdotal histories and testimonies, which he wrote and edited, to satisfy his interest in postwar reconstruction via public scholarship.

Hsu’s diaries are valuable because they fill the gap in our understanding of his early years, and they bring together contexts that have been overlooked in Nanyang historiography. That historiography views the China-Singapore connection, via its publication and institutional histories, as an important genealogy. My biographical method instead asks what was politically and personally at stake in Hsu’s inter-war Nanyang studies. Hsu’s responses to current affairs, especially of China and the Nanyang, from the perspectives of Siam and its southern region of Patani, suggest that the relationships of huaqiao to China and their places of residence are in constant transformation.

As a newly arrived China-loyalist in Siam, Hsu intervened in communities that had perhaps been assimilated through generations of residence, and perhaps more strongly affectively linked to networks of Teochew people, for instance, than to a distant state headquartered in Nanjing. The complex histories of Chinese diaspora continue to be worked out in Hsu’s postwar Singapore, where scholarship written in Chinese or from communist China was seen as politically suspect. Hsu’s diaries recorded events as they unfolded from a viewpoint whose ultimate destiny is unknowable. But they also anticipated the trauma of total war, and Hsu’s decision, as a survivor, to double down on his efforts to fight for the longevity of Chinese education and Nanyang studies in post-1945 Singapore. Hence Hsu’s personal diaries are important because they anticipate the geopolitics and scholarly politics of the South Seas Society some 20 years later.

Naturally, the postwar history of Nanyang archives and scholarly societies would be more familiar to readers. Based mainly at the aforementioned Nanyang University (1956–80), the first Chinese-language university in Southeast Asia, Nanyang Studies crystallised a scholarly generation’s interests in the region they called “home”.96 Notably, Nanyang University (or Nantah) graduates majoring in history and geography fondly recall their ethnographic trip to India, which Hsu led in 1959. Hsu wrote a parttravel memoir, part-cultural-religious history titled Travels to India (1964), and published it as one of 12 books in the Afro-Asian book series (Ya Fei congshu) he edited for Singapore’s Youth Bookstore (Qingnian shuju, 1955– ), which was founded by Chen Mong Chea (Chen Mengzhe, 1920–2016).97 Incidentally, the publication of this series was related to the opening of Nanyang University. The books were used as textbooks, so they sold well and underwent a second print run.98 This was around the time that Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock’s government banned the import of all publications from China (1958), and local publishers cornered the Malayan market in Chinese-language publishing.99 Other well-known book series include the Singaporean and Malayan Literature and Art book series (Xin Ma wenyi congshu) and Literature from the South (Nanfang wencong), which launched the careers of many local writers, such as Han Suyin, Ly Singko (Li Xingke), Miao Xiu, Lin Cantian, Wei Yun, Lian Shisheng, Qiu Xuxu and Zhao Rong.

Folk historians (minjian xueren) wistfully narrate the rise and decline of Nanyang Studies in Singapore (1940–81), and view Hsu’s passing in 1981 as marking the end of an era. After 1981, Nanyang Studies took a turn toward ethnic Chinese studies.100 This calls for an explanation. Nanyang University (1956–80), the first Chinese-language university in Southeast Asia, was forcibly closed around that time, to meet the Singapore government’s globalising efforts in English. The centre of gravity for overseas Chinese studies shifted to departments of Chinese studies at the University of Malaya and National University of Singapore. No studies pursued in Chinese thereafter could escape questions of ethnic identity. The shift from diasporic to local Malayan identities in postwar Nanyang publications, perhaps, creates a paradoxical, uneasy feeling where scholars celebrate creolisation but wonder if it is attached to the heavy cost of assimilation.101 Hsu’s creolised, anti-assimilationist stance in Nanyang studies is worth revisiting. Fledging and open to varied intellectual trends and genealogies, his interwar Nanyang studies imagined a different outcome, and it is important that we do not take its evanescence as a foregone conclusion.

Acknowledgments

I thank Haun Saussy and my reviewer Seng Guo Quan for their comments on an earlier draft of the essay; Kenji Chanon Praepipatmongkol for his help with the Thai; Zhuang Wubin for inspiring conversations; Senior Librarian Seow Peck Ngiam and library staff for their assistance in accessing materials during my fellowship at NLB.

REFERENCES

Amirell, Stefan. “The Blessings and Perils of Female Rule: New Perspectives on the Reigning Queens of Patani, c. 1584–1718.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 42, no. 2 (June 2011): 303–23. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 1983. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 320.54 AND)

—. The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World. New York: Verso Books, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 320.959 AND)

—. “Riddles of Yellow and Red,” New Left Review 97 (January–February 2016)

An, Huanran 安焕然, “Liubang hui “ma xin shi xue 80 nian” huigu” 刘邦辉 “麻心识学80年” 回顾 [Review of Lew Bon Hui’s Ma Xin shixue 80 nian], in Nanfang daxue xuebao 南方大学学__报 [Southern University College Academic Journal] 2 (2014). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 378.595 SUCAJ)

Baker, Christopher John and Pasuk Phongpaichit, A History of Thailand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 BAK)

Barmé, Scot. Luang Wichit Wathakan and the Creation of a Thai Identity. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1993. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.304 BAR)

Bradley, Mark. The World Reimagined: Americans and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Carstens, A.Sharon, “Chinese Publications in Singapore and Malaysia.” In Changing Identities of the Southeast Asian Chinese Since World War II, edited by Jennifer Cushman and Wang Gungwu. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1988, 75–96. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8951059 CHA)

Cassese, Antonio. Human Rights in a Changing World. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1990.

Chaloemtiara, Thak. “Are We Them? Textual and Literary Representations of the Chinese in Twentieth-Century Thailand.” Southeast Asian Studies 3, no. 3 (December 2014): 475–526.

—. “Move Over, Madonna: Luang Wichit Wathakan’s Huang Rak Haew Luk,” in Southeast Asia Over Three Generations: Essays Presented to Benedict R. O’Gorman Anderson, edited by James T. Siegel and Audrey R. Kahin. Ithaca, New York: Southeast Asia Program Publications, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.SOU)

—. Read Till It Shatters: Nationalism and Identity in Modern Thai Literature. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University, 2018.

Chan, Shelly. Diaspora’s Homeland: Modern China in the Age of Global Migration. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.0495108 CHA)

Chantavanich, Supang and Anusorn Limmanee. “From Siamese-Chinese to Chinese-Thai: Political Conditions and Identity Shifts Among the Chinese in Thailand.” In Ethnic Chinese As Southeast Asians, edited by Leo Suryadinata_._ Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1997. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8951059 ETH)

Chen, M. “Zaoqi xin ma huawen shuju cujin xianggang chuban ye de chengzhang” 早期新马华文书局促进香港出版业的成长 [Early Singaporean and Malayan bookstores encouraging the growth of Hong Kong’s publishing industry], Yihe shiji 怡和世纪 [Jardine century] no. 24 (October 2014–January 2015). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 369.25957 OPEHHC)

Chonlaworn, Piyada. “Contesting Law and Order: Legal and Judicial Reform in Southern Thailand in the Late Nineteenth to Early Twentieth Century,” Southeast Asian Studies 3, no. 3 (December 2014): 527–46, accessed Kyoto University Research Information Repository.

Clinton, Maggie. Revolutionary Nativism: Fascism and Culture in China, 1925–1937. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Eaksittipong, Sittihep. “Textualizing the ‘Chinese of Thailand’: Politics, Knowledge, and the Chinese in Thailand During the Cold War.” PhD. Diss., National University of Singapore, 2017.

Eoseewong, Nidhi. Kanmueang Thai Samai Phrajao Krung Thonburi [Thai politics in the time of the King of Thonburi]. Bangkok: Silpawatthanatham Press, 1986.

Fong, Grace. “Writing From Experience: Personal Records of War and Disorder in Jiangnan During the Ming-Qing Transition.” In Military Culture in Imperial China, edited by Nicola Di Cosmo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009, 257–77. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 306.270951 MIL)

Foot, Rosemary. Rights Beyond Borders: The Global Community and the Struggle Over Human Rights in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Gesick, Lorraine. “The Rise and Fall of King Taksin: A Drama of Buddhist Kingship,” in Centers, Symbols, and Hierarchies: Essays on the Classical States of Southeast Asia, edited by Lorraine Gesick. New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, 1983, 87–105. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.CEN)

Greiff, Thomas. “The Principle of Human Rights in Nationalist China: John C. H. Wu and the Ideological Origins of the 1946 Constitution.” China Quarterly no. 103 (September 1985): 441–461. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Fogel, Joshua and Peter G. Zarrow, eds., Imagining the People: Chinese Intellectuals and the Concept of citizenship, 1890–1920. London: M. E. Sharpe, 1997.

Hayton, Bill. “China’s ‘Historic Rights’ in the South China Sea: Made in America?” Diplomat (21 June 2016).

Herzfeld, Michael. “The Conceptual Allure of the West: Dilemmas and Ambiguities of Crypto-Colonialism in Thailand.” In The Ambiguous Allure of the West: Traces of the Colonial in Thailand, edited by Rachel V. Harrison and Peter A. Jackson. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.304 AMB)

Ho, Engseng. “Empire Through Diasporic Eyes: A View From the Other Boat.” Society for Comparative Study and History 46, no. 2 (April 2004): 210–46. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

—. “Inter-Asian Concepts for Mobile Societies.” Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 4 (November 2017): 907–928, accessed Duke University website.

Hong, Lysa. “Stranger Within the Gates”: Knowing Semi-Colonial Siam As Extraterritorials.” Modern Asian Studies 38, no. 2 (May 2004): 327–54. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Ibrahim Syukri, History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2005. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 IBR)

Jerryson, K. Michael. Buddhist Fury: Religion and Violence in Southern Thailand. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 294.337273 JER)

Jory, Patrick. “Books and the Nation: The Making of Thailand’s National Library,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 31, no. 2 (September 2000): 351–73. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Journal of M. Descourvieres, (Thonburi). Dec. 21, 1782, in Launay, Histoire, 309.

Kwong, S. Luke. A Mosaic of the Hundred Days: Personalities, Politics, and Ideas of 1898. Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1984. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 951.03 KWO-[GH])

Landon, Kenneth Parry. The Chinese in Thailand. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.89510593 LAN)

Larson, Jane Leung. “An Association To Save China, the Baohuang Hui 保皇會: A Documentary Account,” China Heritage Quarterly no. 27 (September 2011)

Lee, Sang Kook, “Contentious Development: Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore,” in The Historical Construction of Southeast Asian Studies: Korea and Beyond, edited by Park Seong Woo and Victor T. King. Singapore: ISEAS, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.007105 HIS)

Li Anshang. “Zhongguo huaqiao huaren yanjiu de lishi yu xianzhuang gaishu.” In Huaqiao huaren baike quanshu zong lun juan 华侨华人百科全书总论卷 [Introduction to overseas Chinese encyclopedia] (2014)

Liau, Bingling 廖冰凌. “Qianzai de zhengzhi huayu: Lun nanyang xuezhe xuyunqiao zhi maoxian xiaoshuo ‘shaonian hanghai jia’” 潜在的政治话语:论南洋学者许云樵之冒险小说 ‘少年航海家’ [A hidden political discourse: A study of Hsu Yun-Tsiao’s adventure story, ‘The Young Navigator’], Huawen wenxue (2011): 42–47.

Loos, Tamara Lynn. Subject Siam: Family, Law, and Colonial Modernity in Thailand. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 346.593015 LOO)

McKeown, Adam. “Conceptualizing Chinese Diasporas, 1842 to 1949.” Journal of Asian Studies 58, no. 2 (May 1999): 306–337. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Jory, Patrick and Michael J. Montesano, eds. Thai South and Malay North: Ethnic Interactions on a Plural Peninsula. Singapore: NUS Press, 2008. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.8009593 THA)

Liao, Wenhui 廖文辉, Xuyunqiao pingzhuan 许云樵评传 [A Biography of Hsu Yun-Tsiao]. 新加坡: 八方文化创作室), 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.007202 LWH)

Moore, Aaron William. Writing War: Soldiers Record the Japanese Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 940.5352072 MOO-[WAR])

Ngeow, Chow-Bing, Tek Soon Ling and Pik Shy Fan. “Pursuing Chinese Studies Amidst Identity Politics in Malaysia,” East Asia 31, no. 2 (2014): 103–122.

Ngoi, G. P. “Introduction.” In Liao Wenhui 廖文__辉__, Ma xin shixue 80 nian: Cong “nanyang yanjiu” dao “huaren yanjiu”(1930–2009) 马新史学80年: 从 “南洋研究” 到 “华人研究”(1930–2009) [Eighty years of historiography in Malaysia and Singapore: from “Nanyang studies” to “Chinese studies” (1930–2009)]. Shanghai: Sanlian, 2011. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 907.20595 LWH)

Nguyen, Thi Lan Anh. “Origins of the South China Sea Dispute.” In Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea: Navigating Rough Waters, edited by Jing Huang and Andrew Billo. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, 15–35. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 341.4480916472 TER)

Peyton, Will. “Wellington Koo, Mukden and Multilateralism,” China Story Journal (4 September 2016), accessed Australian National University.

Platt, R. Stephen. Provincial Patriots: The Hunanese and Modern Chinese. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 951.215035 PLA)

Reid, Anthony. “Patani as a Paradigm of Pluralism.” In Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani, edited by Patrick Jory. Singapore: NUS Press, 2013, 3–30. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 GHO)

Reid, Anthony and Daniel Chirot, eds. Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.004951 ESS)

Rowe, T. William. China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 951.03 ROW)

Salmon, Claudine. “C. Hsu Yun Tsiao (1905–1981),” Archipel 25, no. 1 (January 1983): 3–5.

Saussy, Haun and GE Zhaoguang, “Historiography in the Chinese Twentieth Century.” In The Oxford Handbook of Modern Chinese Literatures, edited by Carlos Rojas and Andrea Bachner. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 895.109005 OXF)

Seah, Leander. “Between East Asia and Southeast Asia: Nanyang Studies, Chinese Migration, and National Jinan University, 1927–1940.” Translocal Chinese: East Asian Perspectives 11, no. 1 (February 2017): 30–56.

Skinner, G. William. Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1957. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS ENG325.25109593 SKI)

Soontravanich, Chalong. “Sila Viravong’s Phongsawadan Lao: A Reappraisal.” In Contesting Visions of the Lao Past: Laos Historiography at the Crossroads, edited by Christopher E. Goscha and Soren Ivarsson. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2003, 111–28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.40072 CON)

Svensson, Marina. Debating Human Rights in China: A Conceptual and Political History. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Tang, Xiaobing. “Poetic Revolution, Colonization and Form at the Beginning of Chinese Literature.” In Rethinking the 1898 Reform Period: Political and Cultural Change in Late Qing China, edited by Rebecca E. Karl and Peter Gue Zarrow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 245–265. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 951.035 RET)

Tang, Zhijun 汤志钧 and Tang Renze 汤仁泽, eds., Liang Qichao quan ji 梁启超全集 [Complete works of Liang Qichao], vol. 3. 北京: 北京出版社, 1999. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 085.951 LQC)

Tejapira, Kasian. “Imagined Uncommunity: The Lookjin Middle Class and Thai Official Nationalism.” In Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997, 75–98. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.004951 ESS)

Tsu, Jing. “Extinction and Adventures on the Chinese Diasporic Frontier.” Journal of Chinese Overseas 2, no. 2 (November 2006): 247–68.

Wade, Geoff. “From Chaiya to Pahang: The Eastern Seaboard of the Peninsula As Recorded in Classical Chinese Texts.” in Etudes Sur L’histoire Du Sultanat De Patani, edited by Daniel Perret. [n.p.]: Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, 2005, 375–78.

Wang, Gungwu, “Sojourning: The Chinese Experience in Southeast Asia.” In Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese, edited by Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers and Jennifer Wayne Cushman. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 1–14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.004951 SOJ)

—. The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

—. “Chinese Political Culture and Scholarship About the Malay World.” In Diasporic Chinese Ventures: The Life and Work of Wang Gungwu, edited by Gregor Benton and Hong Liu. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 950.049510092 DIA)

Winichakul, Thongchai. “Writing at the Interstices: Southeast Asian Historians and Postnational Histories in Southeast Asia.” In New Terrains in Southeast Asian History, edited by Abu Talib Ahmad and Liok Ee Tan. Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003, 3–29. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.00725059 NEW)

—. “Modern Historiography in Southeast Asia: The Case of Thailand’s Royalnationalist History.” In A Companion to Global Historical Thought, edited by Prasenjit Duara, Viren Murthy and Andrew Sartori. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014, 257–68.

Wongsurawat, Wasana. “Contending for a Claim on Civilization: The Sino-Siamese Struggle To Control Overseas Chinese Education in Siam.” Journal of Chinese Overseas 4, no. 2 (November 2008): 161–82