In the Tropical Mood: Retracing Liu Yichang’s Years in Singapore (1952–1957)

By Lim Fong Wei

Introduction

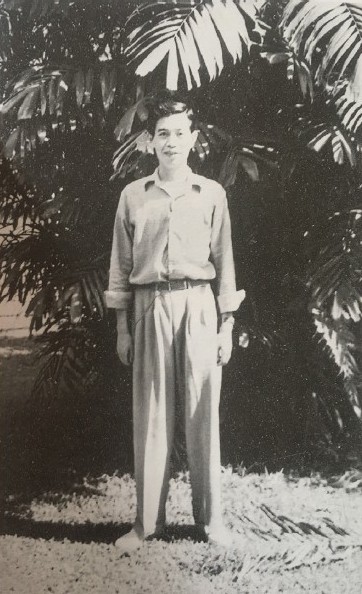

In 2000, a new generation was introduced to Hong Kong writer Liu Yichang (刘以鬯, 7 December 1918 – 8 June 2018) through the technicoloursaturated imagery of Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love and 2046, two films inspired by Liu’s seminal novels Tête-bêche (《对倒》) and The Drinker (《酒徒》, which was considered the first stream-of-consciousness Chinese novel) respectively. The films’ protagonist, a cigarette-puffing newspaper editor and pulp-novelist played by actor Tony Leung, was also loosely based on Liu himself.

Wong’s films may have been set in Hong Kong in the 1960s, but the prime of Liu’s life had been a decade earlier in Singapore in the 1950s, where he, aged 34, experienced the golden era of Singapore’s tabloids, was initiated into the glitzy getai (歌台, live revue) world, fell in love with a beautiful songstress and married a dancer with a beautiful heart.

The diasporic twinning of Hong Kong and Malaya due to political and historical events of the time created a wealth of opportunities that prompted the exchange of commerce, talents and culture. Malaya’s post-war demand for Chinese talents in the publishing and entertainment industries had made Liu’s, and his wife’s, brief stint in Malaya possible, thereby shaping his personal and literary life forever.

In 1952, Liu was headhunted to join the high-profile but short-lived paper Ih Shih Pao (益世报, ISP) in Singapore. He returned to Hong Kong in 1957, ill and disillusioned, after several false starts at establishing his newspaper career. From then on, Liu, as a novelist based in Hong Kong, continued a long and prolific relationship with Singapore’s Nanyang Siang Pau, publishing more than 60 Malayan short stories between 1958 and 1959, followed by an unbroken serialisation of 55 novels from 1970 to 1985, out of which three were set in Singapore.

On the occasion of his centenary, my paper retraces Liu’s Malayan years and attempts to make sense of his life and time here through newspaper archives, newly unearthed novels and published works, as well as interviews with his wife and close friends in Singapore.

This paper examines the overlapping influence of the two distinct but connected worlds that Liu Yichang inhabited in Singapore, specifically the tabloid industry and getai inner circle, which led to the intertwining of the two personas in his inner world, namely the “newspaper man” (报人, often featured in his stories and novels) and the “storyteller who entertained the public” (娱乐大众的小说家). A chronicler of mid-20th-century Singapore society, Liu created a rich body of Malayan work that, though sadly neglected, deserves to be preserved and celebrated as part of our cultural heritage.

First Cut is the Deepest

In June 1952, Liu Yichang had been living in a room on the fourth floor of Nanyang Khek Community Guild (南洋客属总会) when he came to head the Fukan (副刊, supplement) of the new Chinese newspaper, Ih Shih Pao.1 A 10-minute walk down Peck Seah Street, a left turn on Gopeng Street and a right turn took him to his office on Anson Road. He had arrived in Singapore with four Hong Kong veteran editors, Chung Wen Ling (钟文苓), Liu Wenqu (刘问渠), Zhao Shixun (赵世洵) and Zhang Bingzhi (张冰之). Together, they were known as the Five Tigers from Hong Kong. The newspaper was launched on 7 June 1952, and a well-attended cocktail party was held at the Cathay Restaurant on 14 June. At the occasion were the who’s who of Singapore – government officials, Chinese community leaders and business organisation representatives.2 The paper’s future looked promising. Liu Yichang did not expect to lose his first job in Singapore in less than four months.

On 13 October 1952, Nanyang Siang Pau (NYSP) reported the abrupt closure of Liu’s paper: “At 6am yesterday, Ih Shih Pao locked down its office and posted a notice announcing the suspension of its operation.” The headline read: “Three Years of Preparation and They Lasted Four Months”. Fortyseven of the 120 workers were editorial staff and all had been locked out of the building with their personal belongings still inside. Some journalists only found out that they were out a job after they had returned from their assignments.3

Liu should have seen it coming. The paper had already run into financial difficulty barely a month after its launch, and, from mid-August, was unable to pay its employees.4 Three editorial staff, including Zhao Shixun and Chin Kah Chong (陈加昌, who joined Pan-Asia News Agency in 1955 and became Singapore’s first Vietnam War correspondent), submitted a letter signed by all staff to the labour office to seek recourse in recouping salaries and severance pay owed to them.5

The exact dates and chronology of Liu’s movements during this time are muddled. Liu’s biographer, Yi Mingshan (易明善), wrote that the paper had run into dire financial difficulty by end July. Liu and his four Hong Kong colleagues negotiated with the publisher and, failing to get him to sort out the finances, quit and left (“罢笔而去,离开《益世报》”). B.H. Tay, a Singapore Chinese-newspaper historian, however, wrote that the editors had merely gone on “strike” (实行“罢笔”).6 Yi also wrote that “After leaving Ih Shih Pao by end July, Liu was welcome onboard [at] Sin Lit Pau (新力报) as its chief editor”.7 But ISP’s assistant manager had told NYSP two days after ISP’s shutdown that “they had notified immigration authorities to prohibit the Hong Kong employees from staying in Singapore”,8 suggesting that Liu and the other Hong Kong editors had still been in ISP’s employ until its closure in October.

One can only imagine Liu’s devastation – the sudden shock of losing his job, the anger at being unpaid for months (Liu was also battling his ex-wife over alimony during this time9), and being told that he could no longer stay in Singapore. A Lianhe Zaobao write up on ISP’s rout quoted a line from Liu’s story “Old Wong” (老王): “It was a weekend afternoon. I walked to work and was shocked to see the news centre’s door tightly shut…it felt like someone had punched me in the stomach…everything around me suddenly lost its balance”.10

The unfortunate debacle at ISP was to set the tone for Liu’s news career in Malaya over the next six years, playing out against the exciting but volatile backdrop of the 1950s Chinese tabloid boom. This tide had brought Liu to Singapore’s shores, but it would also slosh him around from paper to paper. In Liu’s words, “It was hard for tabloids to survive. After one collapsed, another one would soon be set up, but it wouldn’t be long before it also went down”.11

The Tabloid Boom

The decade of the tabloid boom up until 1959 saw the publication and subsequent demise of over 40 tabloids due to declining readership, financial difficulties and poor management.12 The tabloid boom also coincided with the Malayan Emergency, a period that saw the government frequently banning publications for politically subversive content or shutting them down as a result of the Anti-Yellow Culture Movement. Liu, who had worked for up to 10 tabloids, bore witness to the heady rise and fall of this golden age of tabloid publishing. After ISP, Liu briefly worked as the chief editor for Sin Lit Pau before he was poached by Lien Pang Daily News (《联邦日报》) to head the paper in Kuala Lumpur in 1953.13

Although virtually nothing has been written about Liu’s brief stay in Kuala Lumpur, Popular Melodies (《时代曲》), Liu’s thinly-veiled roman à clef (that has not been read since the end of its serialisation in NYSP in 1971) helps plug the gap. Popular Melodies’ narrator, Zhu Shangren (诸尚仁), bears an uncanny resemblance to Liu. Like Liu, Zhu had also come to Malaya from Hong Kong to work for a newspaper that had quickly folded, causing him to move from one paper to another. Zhu’s response on how he ended up in KL could have been words spoken by Liu himself: “The newspaper I was working for was going through financial difficulties. I had wanted to go back to Hong Kong. It so happened that this paper in Kuala Lumpur was restructuring, and the person in charge came to Singapore to put together a new team. That’s how I ended up here”.14 Eventually, Zhu was given the opportunity to head another tabloid back in Singapore, and he took up the offer even though “the paper treats me well here, but life here is too monotonous. Singapore would suit me better. As a city, Singapore is more vibrant than Kuala Lumpur”.15

In a 2016 interview, Liu provided behind-the-scenes insight into the tabloid newsroom: “I took a train to Kuala Lumpur, and when I first arrived at Lien Pang Daily News, I realised that they didn’t even have a proofreader.

I had to do all the editing, proofreading and layout, from first to last page, all by myself”.16 “Small Papers” (referencing the Chinese term for tabloids) summed up the scale of their set-ups, which required everyone, including the editors, to wear multiple hats. While in Singapore, Liu befriended the famous Singapore calligrapher and writer Chua Boon Hean (蔡文玄, whose pseudonym was Liu Beian (柳北岸)), and often played mahjong at his home. Chua’s son, Chua Lam, a famous Hong Kong columnist, recalled: “It was a pleasure watching [Liu] play mahjong. When the paper called in the middle of their mahjong sessions, he would ask me to set up a side table with writing papers. He treated it like a sewing machine, churning out the articles while he was waiting for the other players to discard their tiles”.17

Back in Singapore, Liu worked for two papers chaired by the Kuala Lumpur construction tycoon Low Yat (刘西蝶). Liu was the supervising editor at Chung Shing Jit Pao (《中兴日报》, CSJP) at 110 Robinson Road.

The broadsheet struggled with its declining readership and often ran into financial difficulties. Liu later became editor and writer at the tabloid Feng Bao (《 锋报》, FB), which was launched in 1953. Chen Mingzong, his friend and former colleague at ISP, was its chief editor. With its smaller set-up, FB’s sales and distribution thrived. It had a high circulation of 20,000 copies, and was crowned the King of the Tabloid (小报王). Liu left soon after its inception, but was rehired in 1954.18

Tabloids of this era were all very competitive, with each vying for its niche audience. Some specialised in entertainment news. The Shaw Brothers film studio published Entertainment News (《娱乐报》) to promote its films and stars, while Happy News was one of the many tabloids that reported on the latest getai news, their songstresses and cabaret girls. Some tabloids took a salacious approach, running pornographic stories and visuals to attract a certain demographic. But not all tabloids were fluff. Some specialised in news from communist China during the Cold War, while others like FB specialised in the exposé of corrupt and illegal activities.19 For Liu, working for such a paper was not without thrill and danger. Soon after its launch, FB exposed an illegal gambling ring in Kuala Lumpur that specialised in tse fa (字花). The crime lord threatened to hurl hand grenades into the FB newsroom, but the paper would not back down, and eventually helped the police crush the organisation.20

Despite enjoying increasing sales, FB was banned on 30 September 1955 by the Malayan government for posing a risk to public security.21 Liu then moved to Life News (《生活报》), a new publication launched by the FB team on 25 October 1955, followed by Shieh Pau (《狮报》) in September 1956. On 24 December 1955, Chen Mingzong, FB’s former chief editor launched a new tabloid Ti Press (《铁报》) with his brother Chen Qing (陈清), and Liu became its chief writer. Ti Press invested a great deal of money in its high-quality tritone printing, which gave its images greater tonal range. Unfortunately, Ti Press’ sales and distribution were disappointing and Liu left when the paper reverted to the economical black-and-white duotone printing for its ninth issue. Interestingly, the paper’s sales picked up under a new editorial team. In March 1956, when Hong Kong movie superstar Li Lihua came to Singapore for the location shoot of the film Rain Storm in Kreta Ayer (风雨牛车水) which opened on 18 September 1956), Ti Press ran daily behind-the-scenes reports, which resulted in soaring sales. About a year later, Kang Pao (《钢报》) was launched on 17 November 1956 with Liu as its chief editor, but he left after three issues.22

Fighting a Lost Cause?

Despite the distressing instability of his job, one thing remained constant for Liu: his love for literature and his quest to promote modern literature through the papers. Liu had always been or doubled up as the editor of the Fukan literary section, a unique platform in Chinese newspapers that had been instrumental in shaping the identity of Malayan – and after Singapore’s departure from the Federation of Malaysia – Malaysian and Singaporean Chinese literature. Liu was undoubtedly the best choice for such a role, as he had been editing literature for a decade before he came to Singapore. In his birth place of Shanghai, Liu had become the editor for the modern literature section of Peace Daily (《和平日报副刊》) in December 1945. A year later, he quit and founded his own publishing company, Huai Zheng Culture Publishing Company (怀正文化社). In 1948, when civil war in China escalated, Liu escaped to Hong Kong. To make ends meet, he became the Fukan editor of several newspapers. Though recognising that “it is impossible to live on literature in Hong Kong”, Liu always found ways to “let serious literature live off commercial publications”.23

Liu continued to negotiate the divide between literature and commercial writing in Singapore. His innovative and beautifully illustrated layouts for Bieshu (别墅), the literary section of Ih Shih Pao, showcased his modern sensibility. For instance, in response to a story that compared slummers to caged birds, Liu pasted cut-outs of pigeons throughout the page, breaking the lines between the articles.24 Despite working for the tabloids, Liu was still celebrated and respected as a serious writer and champion of modern Chinese literature. Even as NYSP covered the drama of ISP’s shocking collapse within its pages, it simultaneously ran advertisements promoting Bright Snow (《雪晴》). Bright Snow was Liu’s first novel published in Singapore (by NYSP) and was initially serialised in Nanfang Evening Post (《南方晚报》), NYSP’s evening paper. Two months later, in December 1952, Liu published his second novel, Dragon Girl (《龙女》).25

Outside of his work, Liu was a generous mentor to young writers. Former Fukan editor of NYSP and Lianhe Zaobao, Xie Ke (pen-name: 谢克; actual name: Seah Khok Chua 佘克泉), recalled meeting Liu at a literary event organised by Sin Lit Pau in 1952, when Xie was a novice writer studying at Chung Cheng High School (branch). Xie would later visit Liu at his residence at Nanyang Khek Community Guild to seek his advice on writing. Xie would visit at noon during weekends, as Liu would have worked until the wee hours of the morning clearing newspaper pages. Liu would buy him dim sum at a nearby teahouse, where they would be entertained by songstresses singing popular tunes. Sometimes, they would take a trishaw to catch a new film. Xie said, “He would read all my writing and give me considered advice and criticism. He even gave me a list of contemporary Chinese authors I [had to] read, and I diligently completed my ‘task’ within half a year”.26 They went on to become lifelong friends, with Liu calling Xie “one of my oldest friends in Singapore”.27 When Liu moved to a Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) flat on the ground floor of Blk 1 Boon Tiong Road, diagonally across from Xie who lived in Blk 4, other young writers continued to knock on Liu’s door for literary advice, and he showed them the same generosity he had shown Xie.28

However, promoting serious literature in Singapore was not easy. The youths who loved literature were not readers of the tabloids Liu edited. Blue collar workers and rural farmers formed 30 percent of their readership, with ladies of the night and women from the performing industries comprising about 25 percent. “The bar girls, dance hostesses, songstresses and socialites were interested in the tabloids because they wanted to be featured in them. Businessmen only formed 10 percent of the readers, and student readers were less than 5 percent”.29 If Liu had encountered difficulties in Hong Kong pushing literature to the masses via their local papers, one can imagine the far greater resistance from his tabloid publishers concerned with appealing to the lowest common denominator. His unrelenting quest would only lead to his disillusionment and disappointment.

Unable to see his future in Singapore, Liu returned to Hong Kong in late 1957. Two years later, on 8 June 1959, four days after the People’s Action Party won the election by a landslide, the Ministry of Home Affairs banned six obscene tabloids, including Ti Press, in an attempt to cultivate a wholesome society, effectively sounding the death knell for Chinese tabloids. In a national broadcast, then Home Affairs Minister Ong Pang Boon said that these obscene tabloids bred an unhealthy view towards life by portraying a world populated by half-naked licentious women and hooligans always out to create trouble.30

Sing Sing Sing: The Getai Inner Circle

Popular Melodies (《时代曲》), a forgotten novel by Liu serialised in Nanyang Siang Pau in 1971, shows him to be an insider and keen observer of the vibrant and glitzy getai (歌台) at the amusement worlds in Singapore in the 1950s. Actor Bai Yan (白言) and queen of Amoy cinema, Zhuang Xuefang (庄雪芳), both getai icons, became his lifelong friends. This side of Liu resembles the writer and dandy who would go on to inspire Tony Leung’s character in Wong Kar Wai’s films In the Mood for Love and 2046.

The novel is an important discovery for two reasons: It offers a rare account of Liu’s life in Singapore in his own voice, as well as a detailed record of getai in its heyday. The novel starts: “Twenty years ago, Zhu [the novel’s narrator] came to Singapore from Hong Kong to work for a newspaper…”. It then goes on to document Zhu’s move to Kuala Lumpur and back to Singapore – the work is a thinly veiled roman à clef that bears an uncanny similarity to Liu’s own experiences.31

Popular Melodies can be read as a companion piece to Singapore Story (《星加坡故事》), an anti-communist melodrama about a newspaper editor’s romantic entanglement with a getai singer that Liu, lured by the high fee, wrote in 1957, shortly before his return to Hong Kong, for the magazine Story Paper (《小说报》) which was backed by the United States Information Service (USIS).32 Popular Melodies, written in the 1970s, sans political agenda, reads more like an eulogy to the vanished getai world.

Liu’s connection with getai was intrinsically linked to his role as a newspaper editor. The newspapers, especially tabloids with a strong focus on entertainment, enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with getai operators: the former needed getai artistes to provide exclusive content to attract readers, while the latter needed the papers to promote their shows and artistes. Zhuang Xuefang, before starring in a string of Amoy movies that propelled her to superstardom, was a getai star in the early 1950s. In her interview with me, she recounted her first meeting with Liu at his Ih Shih Pao office: “We paid him a visit after hearing about the setting up of the paper”.33 Liu confirmed that such public relation practices were the norm in Popular Melodies: “The getai song and dance troupes came and went one after another, like revolving figures on the Chinese lantern. Before the run of each show, each troupe leader would pay their respects to the newspaper’s top management with their key actors and singers. That was how Zhu Shangren became acquainted with both local and Hong Kong getai artistes”.34

Zhu’s/Liu’s privileged position as a writer and newspaper editor granted him insider access to the getai world. Real-life getai personalities made appearances as themselves in Liu’s roman à clef. Zhu describes the first time he was taken backstage: “Tay was chummy with all the singers and actors, first greeting Zhuang Xuefang and Poon Sow Keng (潘秀琼), then shaking hands and sharing jokes with Bai Yan and Guan Xinyi (关新 艺)… Zhuang said to Tay, ‘I’ll be performing for a short period in Kuala Lumpur, but your paper reported that I’d be performing in Borneo. Can you see to it that the error gets amended?’ Everything looked new and fresh to Zhu”.35 According to Liu’s wife, Liu had bonded with actor Bai Yan over their shared philatelic passion.

Liu digressed from Popular’s melodramatic storyline to offer commentaries and observations about the rise of the popular music scene in Malaya and getai’s inner workings. With quick-cutting images, Liu showed how these Chinese songs, influenced by jazz and other popular Western music genres, had touched every aspect of society: “Thanks to the blooming of getai stages in towns big and small all over Malaya, the popular music craze has exploded in the region. Listening to popular songs has become the main recreation for the masses…from school girls to female workers in rubber shoes factories, typesetting workshops, pineapple canning factories and fisheries”.36 In Liu’s novel, Zhu had initially found “these songs low brow, but it was impossible to not be swept up by their infectious melodies and spell”.37

Like Liu, the fictional Zhu also frequented cinemas when he first arrived in Singapore, “but after hanging out with the getai people, his monotonous life became more colourful”.38 This is no small wonder when one imagines the sight and sound of this glitzy, nocturnal world. In the 1950s, getai was at its peak with more than 20 venues offering live performances in the three “worlds”, or amusement parks, namely Great World, New World (both owned by Shaw Organisation) and Happy World (owned by Eng Wah Organisation and later renamed Gay World). These “worlds” that came to life every night from 6pm to midnight were like the kaleidoscopes of the modern age.39 Television only arrived in Singapore in 1963, and these worlds – with several cinemas, restaurants, dancehalls and live venues under each roof – offered their audiences a mind-boggling selection of entertainment ranging from wrestling, boxing, strip-tease, Chinese and Malay operas, to shopping, amusement rides, gaming, cabarets and dancing. Furthermore, these “worlds” were affordable not just for adults but also for youths, making them appealing attractions for the whole family.

Getai, at its peak, was so wildly popular that it could attract as many as 500 patrons a night, and twice the number on nights when business was thriving.40 According to Liu, “Getai’s programme usually went like this: from 8pm to around 1030pm, singers would take turns to sing, ending with a modern play or sketch.” In her memoir, Zhuang Xuefang wrote that during her Shangri La getai days, she had to switch from singing to acting in the same night, an experience that prepared her for acting in Amoy cinema in the late 1950s and 1960s.41

Zhuang described Liu as a serious man of letters,42 but backstage dramas such as the bickering between getai pianists and songstresses fuelled his imagination. In Popular Melodies, the fictional Zhu relished these “real-life dramas… [which were] far more riveting than the sketches on stage”.43 Liu wrote two short stories based on his keen behind-the-scenes observations. “Troupe Leader” (《团长》) is a sympathetic portrayal of a troupe leader who had to handle a motley crew of difficult artistes and creditors. The stress was so great that the man collapsed on stage after announcing “Ladies and Gentlemen”.44 “Getai” (《歌台》) is a zany comedy about a getai owner who insisted on casting a stripper in the play The Savage Land (《原野》) by Cao Yu (曹禺). In “Getai”, the director had walked out in a fit of anger, but the true to the owner’s predictions, the queue for the show began forming way ahead of the play’s 8pm curtain-up.45

Occasionally, Liu would join in the fun and pen Chinese lyrics for Malay and foreign songs. On 7 August 1952, Liu’s former Hong Kong employer Sing Tao Weekly (《星岛周报》) published five of his poems under the title Balinese Charm and Others (《峇厘风情及其他》).46 In an annotation for the poem “Balinese Charm”, Liu wrote “I heard [the song] ‘Balinese Island’ (峇厘岛) when I first came to Singapore. The melody was excellent but the Chinese lyrics were in poor taste. Egged on by my friends, I wrote my own lyrics to the melody, which became ‘Balinese Charm’ (峇厘风情).” The song was based on “Pulau Bali”, an Indonesian folk song. Called “Balinese Island”, the Chinese adaptation was later popularised by Poon Sow Koon. Reality overlapped with fiction once again when protagonist Zhu recounted a similar incident in Popular Melodies: “Worried that their audience would get tired of the same old tunes… some singers would seek out Western and Japanese melodies, and ask Zhu to pen the Chinese lyrics for them. Although writing lyrics wasn’t his forte, he attempted a few…He found it most amusing when he heard songs he wrote being performed on stage”.47

By 1971, Liu had perhaps already forgotten about these songs as Popular Melodies made no mention of the songs Zhu had penned, but now, we know “Balinese Charm” went like this: “I clasp your waist tightly, and you embrace me passionately. Have you brought life and colours to me because you could see how desolate my life has been?” (我紧紧搂住你的细腰,你疯狂地 将我拥抱。莫非你看透我心境萧条,故意赠我一场热闹。)

Not content to stage just slapstick acts, some getai actors and artistes aspired to put up more serious work. Liu, himself trying to feature more serious literature in tabloids, probably found them to be kindred spirits. In Popular Melodies, Liu wrote about an actor named Loke who “is an earnest artiste. He keeps trying to stage famous plays at getai.” Liu also offered his candid opinions of these noble attempts: “As the conditions at getai were generally unfavourable to such staging, some of these plays, even though originally written by famous playwrights, became crudely adapted sketches. Shangren had once watched the staging of Cao Yu’s Thunderstorm by a getai troupe in Singapore. Despite the best efforts of the cast and crew, the end product was less than desirable”.48

In the Mood for Love

Koo Mei: Star-crossed Lovers

The getai world had a direct impact on Liu’s love life in Singapore. It brought Koo Mei (顾媚), with whom he had a short affair, and his second wife Lo Pai Wan (罗佩云), to whom he had been married for over 60 years, into his life.

Koo was a celebrated Hong Kong singer who went on to make a name for herself singing the classic “Everlasting Love” (不了情). On 25 April 1953, Nanyang Siang Pau announced that Koo’s troupe, a Latin America-inspired Argentinian song and dance troupe, would be performing at the Happy World stadium.49

Koo dedicated a chapter to Liu in her juicy tell-all 2006 memoir From Dawn to Dusk (《从破晓的黄昏》). Their first meeting had been flirtatious. She wrote, “We met backstage where he was reporting as a journalist. I told him I had read his articles in the papers. He asked if I knew his name. I said I did, but I didn’t know how to pronounce the word Chang (鬯), and often called him Liu Yi Sha (刘以傻,傻 sha means stupid). I wrote his name in its correct form on a piece of paper, and he kept it in his shirt pocket. After that he would come backstage to see me every night”.50

Koo left the troupe to join Red Sea Getai (满江红歌台) at New World Amusement Park as its contract singer. By this point, Liu and Koo were inseparable. When I asked Zhuang Xuefang about the love affair, she replied, “Koo Mei really liked Liu Yichang”.51

“Liu would accompany me to work every night… After work, we had supper at Katong. We never ran out of things to say to each other. He had gotten divorced a year earlier. His ex-wife, Li Fang Fei (李芳菲, a Chinese actress well-known for her supporting roles in movies) and daughter remained in Hong Kong while he came to Singapore by himself… He was desolate. He was disappointed with his life… I considered Liu to be my first true love… We had fallen deeply in love and exchanged engagement rings,” wrote Koo.52 When Koo’s contract expired, she reluctantly left Singapore, but vowed to return to marry Liu.

A scandal, however, kept them apart. Koo’s visa application was rejected by Singapore’s immigration department on moral grounds. “I was denied entry into Singapore for attempting to break up someone’s family. The person who lodged a complaint against me was Aw San’s (胡山) wife”.53 While in Singapore, Koo had been hotly pursued by Aw San, the second son of Tiger Balm tycoon Aw Boon Haw. Interestingly, a character in Popular Melodies bore an uncanny resemblance to Koo. Liu reshuffled major incidents of his life in Singapore and paired Mei Qin, the character loosely based on Koo, with Zhu’s colleague in a messy love entanglement. In the novel, Mei Qin was similarly denied entry into Singapore on moral grounds.54

Apart, Koo and Liu kept in touch via fervent correspondence. Liu’s wife, who still has Koo Mei’s love letters, confirmed that they corresponded everyday. Koo would sometimes write up to three letters a day to Liu. However these letters could not sustain their love, and they gradually drifted apart. Koo attributed the break up to the loss of her engagement ring. In 1954, she went to Taiwan with an entourage of stars, headlined by Li Lihua, to entertain the Kuomintang troops. In a letter, Koo told Liu that she had been clapping so hard that she accidentally lost her engagement ring. Koo recalled, “Liu didn’t believe me. He thought I wanted to back out from our engagement, and gave me the cold shoulder. Not long after, I found out that he had married”.55

Koo revealed that years after Liu had returned to Hong Kong, he had called her to ask her to return the letters they had written to each other. She said, “He probably thought that he had become a famous author and was afraid that I would sell his letters. I was furious… I must have had at least 200 to 300 love letters from him, but that night when I found out that he had gotten married, I burned them all!”56

Liu said, “Because I was working for the newspapers, a lot of songstresses would actively seek me out to promote themselves. I do not deny that we got along rather well, and we did see each other for two months or so, it certainly did not last for a year as she had claimed. We corresponded when she went back to Hong Kong, and it lasted two or three months. There weren’t as many letters as she claimed… After all we have both gone our separate ways and there really isn’t much to talk about. I met so many singers in the 1950s, including her, and I did not take advantage of a single one of them. I met [Koo] in 1953; two or three years later I met my wife in 1956 and we got married in 1957”.57

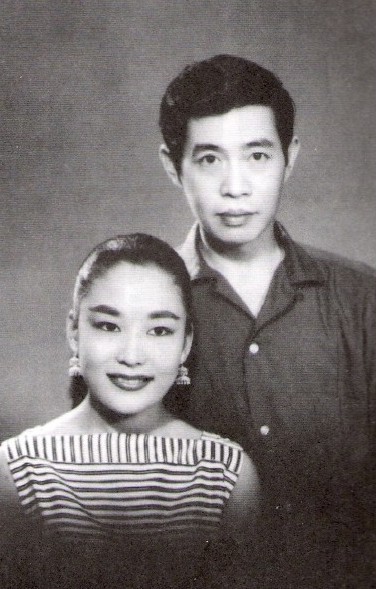

Lo Pai Wan: Everlasting Love

I travelled to Hong Kong in January 2018, five months before Liu’s death, to meet Lo Pai Wan, his wife and the love of his life for 60 years. I did not manage to meet Liu, as he had become increasingly bedridden. Lo had been her husband’s de facto spokesperson since 2016.

Lo had been an accomplished teen dance queen in Hong Kong and was enticed by the flourishing amusement worlds in Singapore. Lo toured Malaya with different troupes three times, in 1953, 1955 and 1956.

Lo was only 18 when she first travelled by ship to Singapore on 14 September 1953, with the Hong Kong Song and Dance Theatre Troupe (香港歌唱舞 蹈剧艺团). She was paired with Tse Liu-Baat (谢鲁八), the veteran King of Dance in Hong Kong (香港舞王). Lo, a young and talented dance queen, was crowned The Jewel of Hong Kong (香港之宝). Lo had been dancing since she was 15 and was one of Tse’s best students, regularly partnering him in dance performances at Hong Kong nightclubs. The troupe decided to tour Singapore “after enjoying enormous success in Indonesia in August 1952”.58

The show opened at the Happy World Stadium on 17 September 1953 with a star-studded cast fronted by Chang Loo (张露), the Shanghainese singer known as The Diva of China (and mother of Hong Kong star Alex To). Chang had shot to fame with the cheery tune “You Are So Beautiful” (你真美丽) and her 1954 hit “Give Me a Kiss” (给我一个吻), a wildly popular Chinese adaptation of the English hit “Seven Lonely Days”.59

Their shows were multicultural brews. Lo and Tse performed “The Spider Lair”, a modern dance adaptation of Journey to the West with Tse undertaking the role of the Monkey King, and Lo, the bewitching temptress.60 They travelled to Kuala Lumpur on 18 October, returning three weeks later with new shows, one of them a Malaya-inspired “Love at the Pasar”(巴刹之恋).61

Lo and Tse returned to Singapore a second time on 20 January 1955 with the Hong Kong Qun Ying Song and Dance Troupe (香港群英歌舞团) for a 10-day performance that ran from 22 January to 7 February 1955 at the Happy World Stadium. That evening, the troupe performed “Malayan Night”, a Malay dance set to Malay music in full Malayan costumes.62

The troupe subsequently headed north to perform at the Majestic Theatre chain in Muar, Seremban, Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, Kampar, Teluk Anson (now Teluk Intan) and Penang. The Majestic Theatre chain was owned by the Singaporean brothers, Ho Khee-Yong (何启荣) and Ho Khee-Siang (何启湘), who made Cantonese films in Malaya under their Kong Ngee film production company.63 Lo elaborated that, in those days, each touring troupe was linked to one cinema chain, “there were the Shaw Brothers chain, Kwang Hwa chain… We would travel to perform at their cinemas and affiliated venues in major cities throughout Malaya. I covered a great part of Peninsular Malaya during my three trips here.”

Lo returned for a third and final time on 27 May 1956. This time Lo and Tse helmed their troupe, the Swan Song and Dance Theatre Troupe (天鹅歌舞剧 艺团), which comprised 25 dancers, comedians and singers. They performed for two weeks from 29 May at the Happy World Stadium.64 This was the momentous trip when Lo fell in love with Liu.

Liu had moved out from his Tiong Bahru SIT flat and taken up residence at the Kam Leng Hotel (金陵大旅店) where Lo and her troupe were based due to its proximity to Happy World. “Contrary to what most people believe,” said Lo during my interview with her, “I had already made Liu Yichang’s acquaintance during my first two trips. However we only truly got to know each other in 1956. Liu’s work at the newsroom used to end very late, and I would return past midnight after my show. We often ran into each other at the lobby, and began to meet there to chat and have a bite or two late into the night.”

Lo shared happy memories with Liu at Raffles Place, back when it was also a thriving shopping hub where the iconic Robinsons and John Little department stores were located. They strolled along Clifford Pier and lovers’ lane at Connaught Drive. In the afternoons, they would hang out at the popular cafe at the former Adelphi Hotel; in the evenings, they had supper at Katong where the park looked out to the sea before it was reclaimed to become Marine Parade.

Liu came down with severe tuberculosis soon after they met, but fortunately Lo was there to provide Liu with the stability he long needed. Five years of drifting from newspaper to newspaper, the lack of jobs and emotional stability, coupled with an unhealthy lifestyle, had finally taken a toll on his health. Liu, who wrote The Drinker in 1963, stayed off alcohol. Cigarettes, romanticised by images of Tony Leung writing while wrapped in a cloud of smoke in Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love and 2046, were Liu’s poison. During our interview, Lo said, “[Liu] was smoking two packs a day. On top of that, his diet had been unhealthy for years. The truth was that things hadn’t been going well for him for a long time, and he was at the lowest point of his life. Luckily, his close friends from Hong Kong, like Chung Wen Ling, got him medical help. A doctor would come to the hotel everyday to give him an injection. Liu’s father had also had lung disease, I believe it could have been a dormant condition in his family. He was getting his daily shot even after returning to Hong Kong. It took him a few years to be completely well.”

After her tour ended, Lo quit showbiz and stayed at the hotel for almost 10 months, devoting herself entirely to nursing Liu back to health. This was when their love deepened. After years of Malayan food, Liu was craving cuisine from his birth place. “We often went to a Shanghainese restaurant from across New World. On days when he wasn’t well, I would take a trishaw there and bring food back for him. There was also a store in Chinatown then that sold foodstuff from Shanghai. I frequently bought food for him there, too,” recalled Lo.

By July 1957, Lo had to leave. “I had no choice. The immigration law was very strict then. Once my one-year visa was up, I had to leave no matter what and apply for re-entry from Hong Kong.” On 8 September 1957, Liu packed up and moved back to Hong Kong to be with Lo, leaving his life in Singapore behind. They married a year later.65

In the course of our interview, Lo revealed, “Liu Yichang was already a permanent resident in Singapore. The newspaper in Kuala Lumpur applied on his behalf. He came back to Hong Kong on a travel visa. He could only re-apply to stay after getting a job, with me as a guarantor.” In Popular Melodies, Liu’s protagonist, Zhu, was also debating if he should stay or go. A part of him wanted to settle down in Malaya: “I like Kuala Lumpur, and I like Singapore even more. I would stay if I married a local Chinese girl”.66 However, Zhu also said, “I like Singapore too, but I still hope to return to Hong Kong one day. I came to Singapore from there, of course I would have feelings for Hong Kong”.67

But Liu returned to Hong Kong for practical reasons. While recuperating in Singapore and without a job at the newspaper, Liu wrote stories for a living. Under the pen-name Ge Li Ge (葛里哥), he wrote Chun Zhi (《春治》), a story about a girl sold to servitude but who ultimately found her own freedom.68 Under another pseudonym, Ling Hu Ling (令狐玲), he retold the story of the Tang dynasty poet in Li Bai Catching the Moon (《李太白捉月》).69 “Singapore Story” (《星加坡故事》) was written around 1956 to 1957 for the Story Paper (《小说报》), a magazine backed by the United States Information Service (USIS).70 But it was not enough to make ends meet. Lo said, “After six years of trying, it was apparent the working style and culture of the newspaper industry in Singapore did not suit him. He also could not support himself as a freelance writer in Singapore. There just weren’t enough publications. Moreover, the tabloids there didn’t pay writers well. Coming back to Hong Kong was an obvious choice.”

Ultimately, it was love that brought Liu back to Hong Kong. In a 2010 interview, Liu bared his heart, “Pai Wan is the best thing to have happened to me. The love she has shown me can only be described as ‘complete devotion’… When her visa expired, I decided to follow her back to Hong Kong and marry her. I vowed to start anew. In order to build a family of our own, I started to write again”.71 Reaffirming their love and devotion, Lo said in a 2016 interview, “We have not been apart for more than 24 hours since we got married”.72

Liu eventually became one of Hong Kong’s most prolific novelists, writing serialised novels and short stories for up to 11 newspapers and magazines, churning out as many as 12,000 words a day. Liu called himself a “wordsmith”, writing to entertain the masses by day, and undertaking serious literature for himself at night. Thanks to his writing, Liu was able to purchase an apartment in Tai Koo Shing, one of Hong Kong’s first major private housing estates, where Liu and Lo have lived ever since.

A Malayan Writer at Heart?

Liu-the-newspaper-man might have left Singapore by the end of 1950s, but the novelist retained a strong connection with Singapore, primarily through his serialised fiction in Nanyang Siang Pau’s (NYSP) Fukan (副刊) literary section from 1957 to 1985. Through the introduction of his good friend, Chung Wen Ling, then chief editor of NYSP (and later Lee Kuan Yew’s press secretary from 1960 until Chung’s passing in 1977), Li Weichen (李微尘) commissioned a collection of short stories from Liu.

Under his pen name Ge Li Ge, inspired by his favourite film star Gregory Peck, Liu wrote more than 60 Malayan short stories, beginning with “Connaught Pavilion”(《康乐亭畔》) which ran on 27 June 1958, and ending with “Servant Girl” (《查某》) which was released on 11 July 1959. Liu wrote at least one story a week, and once wrote eight stories a month, in March 1959. From 1970, over an uninterrupted 15 years, Liu serialised 55 novels in NYSP. From April 1971 to January 1974, he wrote three novels set in Singapore. Rubber Plantation (《树胶园》), about a rubber plantation owner torn between his new family in Malaya and the one he left behind in China, reads like a rewriting and expansion of his 1959 short story “Toiling in Nanyang” (《过番谋生记》). Popular Melodies, his getai novel, is the most valuable find from this era for reasons previously mentioned. Don’t Keep Me Waiting (《别让我等待再等待》) is a melodramatic love story between a newspaper editor and a rich woman who wanted to keep him as her “plaything”.

While Popular Melodies gives detailed insight into the getai trade, Liu’s 1950s Malayan short stories offer vivid looks into bygone Singapore life and society as a whole. These short stories, whose literary merits may not be on par with some of his best Hong Kong stories and novels, provide precious records on the sights and sounds of the time as many of the places, communities and ways of life have since disappeared from our cityscape. These stories double up as his love letters to Singapore. Liu infused so much detail of everyday life in Singapore into these writings that they reminisce and retrace his life here.

One can map out the places Liu had been to through the detailed directions in some of his stories. In “Durian Cake and Leather Shoes” (《榴莲糕与皮鞋》),73 a boy pays five cents for a shuttle bus ride from Tiong Bahru to Kreta Ayer, a journey familiar to Liu as he had lived in both places. In “Night at Bedok” (《勿洛之夜》),74 a man takes a taxi to Bedok with a lady of the night he had met at Happy World to have supper with her. The story details: “The taxi turned into Katong from Mountbatten Road, and drove straight (along East Coast Road) to Bedok beach. I stole a kiss from her when the taxi drove past Hua Yu Villa (华友别墅)”. The villa was an entertainment club that was probably the precursor to the current Hua Yu Wee restaurant on 462 Upper East Coast Road.

“On the Bus From Singapore to Malaysia” (《新马道上》)75 tells of an encounter between a down-and-out man going to work in Malacca and a young woman returning home to Muar. Liu details their brief affair through the stops along their journey: their eyes meet at the bus station outside the Beach Road cinema; they sit together and strike up a conversation as the bus progresses to Johor Bahru via Bukit Timah Road, past Beauty World Amusement Park; at Batu Pahat, they get off the bus and flirt over snacks at a kopitiam (coffee shop). Back on the bus, the man falls asleep and mistakes her for a petty thief when he feels her hand in his pocket. After she gets off the bus at Muar, he finds out that she had actually left him 50 dollars as well as a note, wishing him well in his new life in Malacca. “Night Train from Singapore to KL” (《在新隆夜邮车上》) employs a similar method of storytelling.76

During his interview with me, Xie Ke recalled that while Liu would realistically and poignantly depict the hardships of the underclass, he also portrayed them as multifaceted characters capable of fun and seeking to escape from the drudgery of their lives. This would explain the leisurely pursuits woven into these stories, a lifestyle that was familiar to Liu who frequented getai, cinemas and other entertainment venues.

“Evening Dress”(《晚礼服》)77 is set in a high-end boutique near the Aurora department store once located at High Street (水仙门), one of Singapore’s most exciting shopping districts then. Robinsons at Raffles Place was frequently mentioned in his stories. “A Visitor from Johor” (《柔佛来客》)78 sets the scene of a confrontation between the wife and mistress of a rubber plantation owner at the now-demolished Adelphi Hotel cafe, which Liu once frequented with his wife. Watching movies at Odeon, Cathay and Capitol was one of Liu’s favourite pastimes. His erotically-charged “Midnight Show”(《半夜场》)79 depicts a chance meeting between a man and a vamp at the Odeon. Liu loved going to the races and the racecourse was the backdrop of “A Comedy at the Racecourse” (《马场喜剧》)80 and “The Drinker” (《酒徒》, not Liu’s seminal novel of the same name).81

Liu’s characters were often found indulging in the great Singapore pastime of eating at Tai Thong restaurant at Happy World Amusement Park; enjoying prawn noodles at Amoy Street, fried kway teow at Connaught Drive Park’s hawker centre, midnight supper and satay at Katong Park as well as Bedok Beach. He even name-checked the once famous Swee Kee Chicken Rice shop at Middle Road.82

Liu’s dazzling cast of characters hailed from all walks of life, from tycoons to coolies, covering the gamut of the social stratum. “Kuala Lumpur at the Blink of an Eye” (《瞬息吉隆坡》)83 is a moving tribute to Yap Ah Loy, the kapitan cina of Kuala Lumpur who, on his death bed on 15 April 1885, still dreamt of setting up schools, hospitals and charities in his hometown in China after fighting for the welfare of miners and countless Chinese immigrants in Malaya his whole life. “Ah Sum” (《阿婶》)84 portrays the difficulty of hiring domestic helpers in Singapore through the comedic portraiture of a demanding domestic worker who would only work if the radio were tuned to her favourite storytelling programme when she worked. She demanded a cut of her employer’s mahjong winnings, insisted on five curry meals a week, and that she be allowed to sell cigarettes at the market every night. “Ismail” (《伊士迈》)85 is a heartbreaking story about a downand- out Malay man who went from selling first day covers at Robinson Road to pimping his 19-year-old wife to strangers.

Liu’s impressive ease in using colloquial terms shows how immersed he had been in Singapore’s culture. Shaped by Malaya’s melting-pot society, Liu’s Malayan stories take on a distinctly Malayan and Singapore identity.

Before the standardisation of Mandarin, Singapore’s spoken and written Chinese was influenced by its major dialect groups such as Cantonese and Hokkien. Liu’s generous use of dialect reflected the diversity of Singapore’s Chinese diaspora. He used Cantonese words such as: 扣(dollar), 老虎纸 (tiger paper, referring to the Straits dollars that featured a tiger on one side) and 乌龟婆(female pimp) and Hokkien terms like: 暗牌 (secret detective), 大狗 (big dog, constable), 头家 (boss) and 乌头饭 (literally meaning black bean rice, a euphemism for jail time), and 红毛厝 (a Western-style concrete home).86

Malay, Indian and English words were similarly peppered throughout his stories, sometimes spelled out in letters, but mostly written phonically in Chinese, such as: 羔呸 (kopi, meaning coffee), 啰知 (Cantonese pronunciation of roti, meaning bread), 吉埃 (kedai, Malay for small shop), 马打 (mata-mata, referring to the police), 马打楼 (police station) and 则知 (chetti/chetty referring to moneylenders).87

The interaction between different races was the norm in Liu’s Malayan stories. His “Chinatown” was a multicultural one that included an image of Malay hawkers grilling mutton satay along five-footways (“A Morning in Kreta Ayer”,《牛车水之晨》).88 In the thriller “Robbery in the Coconut Grove” (《椰林抢劫》),89 Hassan, a Malay constable, teams up with his Chinese colleague, Ah Lark (阿六), to solve a shoot-and-run robbery with a shocking ending. In “Blue Gemstone” (《蓝宝石》),90 two Chinese men luck out when they get a bargain from a lonely Indian jeweller in Arab Street.

Conclusion

Liu’s Malayan fiction clearly reflects the Merdeka spirit that was sweeping through Malaya and its literary scene in the 1950s. Liu’s time in Singapore (1952–1957) coincided with the island’s push for independence and decolonisation. As an author with a keen eye for his environment, and especially as a “newspaper man” up-to-date with current affairs and news, Liu certainly would have been attuned to Singapore’s 1955 General Election that allowed locals to elect a majority of seats, as well as the subsequent Merdeka talks in 1956 and 1957. Liu’s two worlds in Singapore, his professional newspaper one, as well as his personal one at the amusement parks and other places of entertainment that kept him close to the pulse and sentiment of the masses, converged in his writing, against the backdrop of a country’s battle for social and political change.

The majority of Malayan Chinese literature as well as Chinese print media during this period increasingly advocated moving away from diasporic and immigrant mindsets toward forging a Malayan identity through embracing and celebrating the multiculturalism of multiethnic communities. Newspaper and literary publications focused more on Malayan culture and lifestyle to promote a sense of local affiliation. Liu’s Malayan fiction clearly carries the hallmark of a Merdeka-conscious Malayan author.

Liu even used the word Merdeka (“默迪卡”). According to an article in Cathay Film Organisation’s entertainment periodical International Screen, Liu’s novel Malay Girl (《马来姑娘》) was to be made into a film starring Linda Lin Dai. In Liu’s article “Why I have written Malay Girl”, he explains: “Malaya has just ‘Merdeka’ed’, and the different races live in harmony. In the story, the Malay live on the east side of the river, and the Chinese live on the west. The river comes between them, but the bridge that connects them represents unity. It unites all ethnic groups and will help strengthen the newly born Malaya”.91 Alas, the film was never made.

Judging from Liu’s vivid depictions of life in Singapore, his keen ear for the Malayan lingua franca, and his astute sense of place, one cannot help but wonder, had Liu chosen to stay in Singapore, would he have gone on to become one of Singapore’s most prolific writers from the last century? No doubt, even though he ultimately made Hong Kong his home, and final resting place, Liu’s impact on Malayan literature, as well as his invaluable insights into life in Singapore, should continue to be examined, explored and studied.

REFERENCES

Kong, Kam Yoke. The Majestic Theatre (大华戏院): Where Chinese Opera Ruled, 26 June 2012. (From National Library Online)

“Cǎixié zì nánměi rèqíng gēwǔ de jīnghuá āgēntíng gēwǔ tuán jíjiāng nán yóu yóu bì hǔ dānrèn tuán zhǎng, guō xiùzhēn, gù mèi, lù fēn, yíng zǐ, céngqǐpíng děng, dōu shì huánán de zhùmíng gēxīng” 采撷自南美热情歌舞的精华 阿根廷歌舞团即将南游 由毕虎担任团长,郭秀珍、顾媚、鹭芬、莹子、曾绮萍等,都是华南的著名歌星 [Argentinian song and dance troupe that encapsulates the essence of Latin-American songs and dances will be travelling south – The troupe features Bi Hu as its leader, and includes other famous singers of South China, such as Guo Xiu Zhen, Koo Mei, Lu Fen, Ying Zi and Zeng Qi Ping.], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 26 March 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

Cai Lam 蔡澜, “Cai lan, chongfeng liu yi chang xiansheng” 重逢刘以鬯先生 [Meeting Mr. Liu Yichang Again], Next Magazine 壹週刊 (6 December 2015)

Chen, Zhiming 陈志明, 刘以鬯先生访问记 [An interview with Mr. Liu Yichang], Chinawriter, 26 December 2016.

“Choubei san nian jingying si yue yishi bao zidong tingye quanti zhiyuan gongyou shiqian quan wei wen zhi jiang qing laogong si dai suo suo jiqian xinshui” 筹备三年经营四月益世报自动停业全体职员工友事前全未闻知将请劳工司代索所积欠薪水 [Three years of preparation and they lasted four months, Ih Shih Pao has ceased operation, while all staff were not informed beforehand. The labour office will be asked to retrieve the salary owned on behalf of the affected staff], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 13 October 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

“Dì 1 yè guǎnggào zhuānlán 1” 第1页广告专栏1 [Advertisement for Liu Yichang’s novel Bright Snow], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 13 October 1952, 1 (From NewspaperSG)

“Fukan ban ‘bieshu’” 副刊版“別墅” [Fukan section], Yi Shi Bao 益世报, 14 July 1952. 4. (Microfilm NL3619)

Gu Mei, 顾媚, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn: Gù mèi huíyìlù 从破晓的黄昏: 顾媚回忆录 [From dawn to dusk: The memoir of Koo Mei] (香港: 三联书店(香港)有限公司出版), 2016)

Lianhe Zaobao. Li, Huiling 李慧玲, “‘Dui dao” zouhong chile 30 nian” “对倒” 走红迟了30年 [Interview with Liu Yichang, the godfather of Hong Kong literature, the popularity of Tete-beche that comes 30 years late]. 11 June 2001, 33. (From NewspaperSG)

Lim, Tin Seng. “Old-World Amusement Parks,” Biblioasia 12, no. 1 (April–June 2016)

Liu Yichang, 刘以鬯, “Wǒ wèishéme xiě mǎ lái gūniáng” 我为什么写马来姑娘 [Why I have written Malay Girl], International Screen Magazine 国__际电影 no. 45 (July 1959): 10–11.

—. Re dai feng yu 热带风雨 [Stories of the tropics] (香港: 获益出版事业有限公司, 2010). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS C813.4 LYC)

—. Xianggang duanpian xiaoshuo xuan: wushi niandai 香港短篇小说选: 五十年代 [Selected Hong Kong short stories in the fifties] (香港: 天地图书公司, 1997), 2 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTSH C813.4 XGD)

“Liu yi chang de shi/xudingming” 刘以鬯的诗/许定铭 [The poems of Liu Yichang/ Xu Dingming], Takung Pao, 大公报, 13 September 2015.

Lizi 栗子, “Gu mei de chulian” 媚的初恋 [Koo Mei’s first love], Mypaper, 9 September 2011.

Nanyang Siang Pau. “Yìshì bào jīn chén shí shí kāiqǐ dàmén yǐbiàn zhígōng qǔchū sīwù” 益世报今晨十时开启大门以便职工取出私物 [Ih Shih Pao opened its door at 10 this morning for their employees to retrieve personal belongings]. 15 October 1952, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Cǎixié zì nánměi rèqíng gēwǔ de jīnghuá āgēntíng gēwǔ tuán jíjiāng nán yóu yóu bì hǔ dānrèn tuán zhǎng, guō xiùzhēn, gù mèi, lù fēn, yíng zǐ, céngqǐpíng děng, dōu shì huánán de zhùmíng gēxīng” 采撷自南美热情歌舞的精华 阿根廷歌舞团即将南游 由毕虎担任团长,郭秀珍、顾媚、鹭芬、莹子、曾绮萍等,都是华南的著名歌星 [Argentinian song and dance troupe that encapsulates the essence of Latin-American songs and dances will be travelling south – The troupe features Bi Hu as its leader, and includes other famous singers of South China, such as Guo Xiu Zhen, Koo Mei, Lu Fen, Ying Zi and Zeng Qi Ping.], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 26 March 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Jièshào bù rì yóu gǎng dǐ xīng de xiānggǎng gēchàng wǔdǎo jù yì tuán——tā de lǐxiǎng shì xiǎng bǎ xiānggǎng de zhēnzhèng yìshù jièshào dào xīng zhōu, ér zài xīng xuéxí gèng hǎo de yìshù dài huí xiānggǎng qù” 介绍不日由港抵星的香港歌唱舞蹈剧艺团——它的理想是想把香港的真正艺术介绍到星洲,而在星学习更好的艺术带回香港去 [Introducing a song and dance troupe from Hong Kong that will be coming to Singapore – its ideal is to bring the real art of Hong Kong to Singapore and to improve on their art in Singapore]. 3 September 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Xiānggǎng gēwǔ jùtuán yīxíng shíqī rén zuó shā dào zhāng lù jīnrì fēi lái shíqī rì yīqǐ shàngyǎn” 香港歌舞剧团 一行十七人昨杀到 张露今日飞来十七日一起上演 [A publicity article announcing Hong Kong song and dance theatre troupe’s performance featuring Chang Loo on 17 Sep 1953]. 15 September 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Kuàilè shìjiè tǐyùguǎn xiāng tuán jīn wǎn yòu yī jù xiàn “módēng pán sī dòng” jīn wǎn xiàn yǎn” 快乐世界体育馆 香团今晚又一巨献 “摩登盘丝洞”今晚献演 [Another great performance by the Hong Kong troupe at Happy World Stadium, “The Spider Lair” opens tonight]. 11 October 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Xiānggǎng gēwǔ tuán jīn wǎn tuīchū dà wǔjù ‘yù tuǐ língkōng’” 香港歌舞团今晚推出大舞剧“玉腿凌空” [Hong Kong song and dance troupe presents a new dance act tonight]. 6 November 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Xiānggǎng qúnyīng gēwǔ tuán zài kuàilè shìjiè yǎnchū gēwǔ jù chōngmǎn shīqínghuàyì zhāng lù de gēshēng zuì shòu zànshǎng” 香港群英歌舞团 在快乐世界演出 歌舞剧充满诗情画意 张露的歌声最受赞赏 [Hong Kong Song and Dance Troupe performing at Happy World – Their musical is poetic and Chang Loo’s singing is highly praised]. 23 January 1955, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Xiè lǔ bā luópèiyún lǐngdǎo tiān’é gēwǔ jù yì tuán èrshíwǔ rén zuó dǐ xīng èrshíjiǔ wǎn qǐ zài kuàilè shìjiè yǎnchū” 谢鲁八罗佩云领导 天鹅歌舞剧艺团 二十五人昨抵星 二十九晚起在快乐世界演出 [The 25 artistes from the Swan Song and Dance Troupe led by Tse Liu-Baat and Lo Pai Wan arrived in Singapore yesterday and will be performing on the stage of Happy World Stadium from May 29th]. 27 May 1956, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Ge Li Ge 葛里哥, Chun Zhi 春治. 12 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 14 January 1957, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 15 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 16 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 17 January 1957, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 18 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 19 January 1957, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 21 January 1957, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 22 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 23 January 1957, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 24 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Chun Zhi 春治. 25 January 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Ling Hui Ling 令狐玲. “Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 1 May 1957, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 3 May 1957, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 4 May 1957, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 7 May 1957, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 6 May 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 8 May 1957, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 9 May 1957, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 10 May 1957, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Lǐ tàibái zhuō yuè” 李太白捉月 [Li Bai catching the moon]. 11 May 1957, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥. “Liúlián gāo yǔ pixie” 榴莲糕与皮鞋 [Durian cake and leather shoes]. 11 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wǎn lǐfú” 晚礼服 [Evening dress]. 21 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Mǎchǎng xǐjù” 马场喜剧 [A comedy at the racecourse]. 25 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Yī shì mài” 伊士迈 [Ismail]. 4 August 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Róufú láikè” 柔佛来客 [A visitor from Johor]. 6 October 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Xīn mǎ dàoshàng” 新马道上 [On the bus from Singapore to Malaysia]. 5 November 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Lánbǎoshí (liú yǐ chàng bǐmíng)” 蓝宝石 (刘以鬯笔名) [Blue gemstone (Liu Yichang’s pseudonym)]. 8 December 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Yē lín qiǎngjié” 椰林抢劫 [Robbery in the coconut grove]. 15 January 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Zài xīn lóng yè yóu chē shàng” 在新隆夜邮车上 [Night train from Singapore to KL]. 3 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Niú chē shuǐ zhī chén” 牛车水之晨 [A morning in Kreta Ayer]. 10 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Ā shěn” 阿嬸 [Ah Sum]. 20 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Bànyè chǎng” 半夜场 [Midnight show]. 24 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Shùnxī jílóngpō” 瞬息吉隆坡 [Kuala Lumpur at the blink of an eye]. 14 April 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Jiǔtú” 酒徒 [The drinker]. 21 April 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wù luò zhī yè” 勿洛之夜 [Night at Bedok]. 26 May 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Gē tái” 歌台 [Getai]. 30 May 1959, 15. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Supplement. “Tuán zhǎng” 团长 [Troupe leader]. 2 June 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 25 April 1971, 24. (Microfilm NL6794)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 27 April 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6794)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 5 May 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 6 May 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 1 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 2 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 3 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 4 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 8 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 14 August 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6812)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 15 August 1971, 28. (Microfilm NL6812)

—. 时代曲 [Popular melodies]. 16 August 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6812)

Su, Zhangkai 苏章恺, Yang Minghui 杨明慧 and Du Hanbin 杜汉彬, Xue ni fang zong: Zhuang Xuefang 雪霓芳踪: 庄雪芳 [Traces of Xuenifang: Zhuang Xuefang] (Singapore: 玲子传媒私人有限公司, 2017). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 791.43028092 SZK)

“Xianggang hang xun, xianggang ying quan li fangfei yu gu mei de jiushi xin ye” 香港航讯,香港影圈李芳菲与顾媚的旧事新页 [Old and new stories about Li Fangfei and Koo Mei], United Daily News 联合报, 22 September 1957, 6.

Xie Ke 谢克, Wo de di yi ben shu 我的第一本书 [My first book] (9 June 2011)

Yi Mingshan 易明善, Liu yi chang chuan 刘以鬯传 [Biography of Liu Yichang] (香港: 明报出版社, 1997)

NOTES

-

Xie Ke 谢克, Wo de di yi ben shu 我的第一本书 [My first book] (9 June 2011); Xie Ke was a veteran Fukan (literary) editor at Nanyang Siang Pau and Lianhe Zaobao from the 1970s to late 1990s. He was also one of Liu’s oldest friends in Singapore. In this essay about his literary journey, he talks about Liu’s influence on his writing: “一九五二年,我在《新力报》举办的文艺集会上,认识了从香港到新加坡来担任《益世报》主笔的著名小说家刘以鬯先生。刘先生平易近人,热心奖掖后进,深受文艺青年欢迎。那时,刘先生自己一个人住在柏城街南洋客属总会四楼,我时常星期天中午去找他,向他请教一些写作问题。每一次,他都很认真地指导我,使我获益不浅”. (“In 1952, at a literary gathering organised by Sin Lit Pau, I [Xie Ke] met Mr. Liu Yi-chang, an eminent Hong Kong writer who had come to Singapore to write for Ih Shih Pao. Mr. Liu was approachable and well-loved by literary youth because he is very encouraging towards us. Mr. Liu lived on the fourth floor of Nanyang Khek Community Guild House on Peck Seah Street then. I would often visit him on Sunday to seek his advice on writing. I have benefitted immensely from his mentorship.”) ↩

-

“Choubei san nian jingying si yue yishi bao zidong tingye quanti zhiyuan gongyou shiqian quan wei wen zhi jiang qing laogong si dai suo suo jiqian xinshui” 筹备三年经营四月益世报自动停业全体职员工友事前全未闻知将请劳工司代索所积欠薪水 [Three years of preparation and they lasted four months, Ih Shih Pao has ceased operation, while all staff were not informed beforehand. The labour office will be asked to retrieve the salary owned on behalf of the affected staff], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 13 October 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Choubei san nian jingying si yue yishi bao zidong tingye quanti zhiyuan gongyou shiqian quan wei wen zhi jiang qing laogong si dai suo suo jiqian xinshui.” ↩

-

“Choubei san nian jingying si yue yishi bao zidong tingye quanti zhiyuan gongyou shiqian quan wei wen zhi jiang qing laogong si dai suo suo jiqian xinshui.” ↩

-

Yi Mingshan 易明善, Liu yi chang chuan 刘以鬯传 [Biography of Liu Yichang] (香港: 明报出版社, 1997), 54. ↩

-

Zheng Wenhui 郑文辉, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972 新加坡华文报业史: 1881–1972 [History of Chinese newspapers in Singapore: 1881–1972] (新加坡: 新马出版印刷公司, 1973), 67. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 079.5957 TBH) ↩

-

Yi, Liu yi chang chuan, 54. ↩

-

“Yishi bao jin chen shi shi kaiqi damen yibian zhigong quchu siwu” 益世報今晨十時開啟大門以便職工取出私物 [Ih Shih Pau opened its door at 10 this morning for their employees to retrieve personal belongings]. Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 15 October 1952, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lizi 栗子, “Gu mei de chulian” 媚的初恋 [Koo Mei’s first love], Mypaper, 9 September 2011; “Xianggang hang xun, xianggang ying quan li fangfei yu gu mei de jiushi xin ye” 香港航讯,香港影圈李芳菲与顾媚的旧事新页 [Old and new stories about Li Fangfei and Koo Mei], United Daily News 联合报, 22 September 1957, 6. ↩

-

Zhang Xinghong 章星虹, “Xiangjiang bao ren zai shi cheng liu yi chang zai chengzhong de san ge luojiao dian” 香江报人在狮城 刘以鬯在城中的三个落脚点 [Hong Kong newspaper man in Singapore, Liu Yichang’s three residences in Singapore], Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, 28 October 2013. ↩

-

“Xiangjiang bao ren zai shi cheng liu yi chang zai chengzhong de san ge luojiao dian.” ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 73, 83. ↩

-

Yi, Liu yi chang chuan, 55. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 5 May 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 8 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Chen Zhiming 陈志明, 刘以鬯先生访问记 [An interview with Mr. Liu Yichang], Chinawriter, 26 December 2016. ↩

-

Cai Lam 蔡澜, Cai lan, chongfeng liu yi chang xiansheng 重逢刘以鬯先生 [Meeting Mr. Liu Yichang Again], Next Magazine 壹週刊, 6 December 2015. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 77. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 75–76. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 77. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 77. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 79–81; Chen, interview, 26 December 2016 ↩

-

Yi, Liu yi chang chuan, 52. ↩

-

“Fukan ban ‘bieshu’” 副刊版“別墅” [Fukan section], Yi Shi Bao 益世报, 14 July 1952. 4. (Microfilm NL3619) ↩

-

“Dì 1 yè guǎnggào zhuānlán 1” 第1页广告专栏1 [Advertisement for Liu Yichang’s novel Bright Snow], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 13 October 1952, 1 (From NewspaperSG). (Published by Nanyang Siang Pau, this appeared in the newspaper the same day it ran the news of Ih Shih Pao’s closure.) ↩

-

Lim Fong Wei’s interviews with Xie Ke (谢克), Oct 2017. ↩

-

Lim, interviews with Xie Ke (谢克), Oct 2017. ↩

-

Li Huiling 李慧玲, “‘Dui dao” zouhong chile 30 nian” “对倒” 走红迟了30年 [Interview with Liu Yichang, the godfather of Hong Kong literature, the popularity of Tete-beche that comes 30 years late], Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, 11 June 2001, 33. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 82. ↩

-

Zheng, Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972, 83–84. ↩

-

Liu Yichang, 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 25 April 1971, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, comp., Xianggang duanpian xiaoshuo xuan: wushi niandai 香港短篇小说选: 五十年代 [Selected Hong Kong short stories in the fifties] (香港: 天地图书公司, 1997), 2 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTSH C813.4 XGD); Zheng Mingren 郑明仁, Liu yi chang yu san hao zi xiaoshuo 刘以鬯与三毫子小说 [Liu Yichang and His 30-Cent Pulp Novels], Ming Pao 明报, 26 October 2016. ↩

-

Lim Fong Wei’s interview with Zhuang Xuefang, 16 Dec 2017. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 1 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 27 April 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6794) ↩

-

“Shídài qū,” 1 June 1971. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 4 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 3 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Lim Tin Seng, “Old-World Amusement Parks,” Biblioasia 12, no. 1 (April–June 2016) ↩

-

Lim, “Old-World Amusement Parks.” ↩

-

Su, Zhangkai 苏章恺, Yang Minghui 杨明慧 and Du Hanbin 杜汉彬, Xue ni fang zong: Zhuang Xuefang 雪霓芳踪: 庄雪芳 [Traces of Xuenifang: Zhuang Xuefang] (Singapore: 玲子传媒私人有限公司, 2017), 48–55. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 791.43028092 SZK) ↩

-

Lim Fong Wei’s interview with Zhuang Xuefang, 16 Dec 2017. ↩

-

Liu, “Shídài qū,” 3 June 1971. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Tuán zhǎng” 团长 [Troupe leader], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 2 June 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé lǐ gē 葛里哥, “Gē tái” 歌台 [Getai], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 30 May 1959, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Liu yi chang de shi/xudingming” 刘以鬯的诗/许定铭 [The poems of Liu Yichang/ Xu Dingming], Takung Pao, 大公报, 13 September 2015. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 8 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 2 June 1971, 7. (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

“Cǎixié zì nánměi rèqíng gēwǔ de jīnghuá āgēntíng gēwǔ tuán jíjiāng nán yóu yóu bì hǔ dānrèn tuán zhǎng, guō xiùzhēn, gù mèi, lù fēn, yíng zǐ, céngqǐpíng děng, dōu shì huánán de zhùmíng gēxīng” 采撷自南美热情歌舞的精华 阿根廷歌舞团即将南游 由毕虎担任团长,郭秀珍、顾媚、鹭芬、莹子、曾绮萍等,都是华南的著名歌星 [Argentinian song and dance troupe that encapsulates the essence of Latin-American songs and dances will be travelling south – The troupe features Bi Hu as its leader, and includes other famous singers of South China, such as Guo Xiu Zhen, Koo Mei, Lu Fen, Ying Zi and Zeng Qi Ping.], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 26 March 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gu Mei, 顾媚, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn: Gù mèi huíyìlù 从破晓的黄昏: 顾媚回忆录 [From dawn to dusk: The memoir of Koo Mei] (香港: 三联书店(香港)有限公司出版), 2016), 76. ↩

-

Lim Fong Wei’s Interview with Zhuang Xuefang, 16 Dec 2017. ↩

-

Gu, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn, 77. ↩

-

Gu, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn, 78. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 14 August 1971, 7 (Microfilm NL6812); Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 15 August 1971, 28. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gu, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn, 79–81. ↩

-

Gu, Cóng pòxiǎo de huánghūn, 81–92. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, Re dai feng yu 热带风雨 [Stories of the tropics] (香港: 获益出版事业有限公司, 2010), 333–34. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS C813.4 LYC) ↩

-

“Jièshào bù rì yóu gǎng dǐ xīng de xiānggǎng gēchàng wǔdǎo jù yì tuán——tā de lǐxiǎng shì xiǎng bǎ xiānggǎng de zhēnzhèng yìshù jièshào dào xīng zhōu, ér zài xīng xuéxí gèng hǎo de yìshù dài huí xiānggǎng qù” 介绍不日由港抵星的香港歌唱舞蹈剧艺团——它的理想是想把香港的真正艺术介绍到星洲,而在星学习更好的艺术带回香港去 [Introducing a song and dance troupe from Hong Kong that will be coming to Singapore – its ideal is to bring the real art of Hong Kong to Singapore and to improve on their art in Singapore], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 3 September 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Xiānggǎng gēwǔ jùtuán yīxíng shíqī rén zuó shā dào zhāng lù jīnrì fēi lái shíqī rì yīqǐ shàngyǎn” 香港歌舞剧团 一行十七人昨杀到 张露今日飞来十七日一起上演 [A publicity article announcing Hong Kong song and dance theatre troupe’s performance featuring Chang Loo on 17 Sep 1953], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 15 September 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Kuàilè shìjiè tǐyùguǎn xiāng tuán jīn wǎn yòu yī jù xiàn “módēng pán sī dòng” jīn wǎn xiàn yǎn” 快乐世界体育馆 香团今晚又一巨献 “摩登盘丝洞”今晚献演 [Another great performance by the Hong Kong troupe at Happy World Stadium, “The Spider Lair” opens tonight], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 11 October 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Xiānggǎng gēwǔ tuán jīn wǎn tuīchū dà wǔjù ‘yù tuǐ língkōng’” 香港歌舞团今晚推出大舞剧“玉腿凌空” [Hong Kong song and dance troupe presents a new dance act tonight], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 6 November 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Xiānggǎng qúnyīng gēwǔ tuán zài kuàilè shìjiè yǎnchū gēwǔ jù chōngmǎn shīqínghuàyì zhāng lù de gēshēng zuì shòu zànshǎng” 香港群英歌舞团 在快乐世界演出 歌舞剧充满诗情画意 张露的歌声最受赞赏 [Hong Kong Song and Dance Troupe performing at Happy World – Their musical is poetic and Chang Loo’s singing is highly praised], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 23 January 1955, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kong Kam Yoke, The Majestic Theatre (大华戏院): Where Chinese Opera Ruled, 26 June 2012. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“Xiè lǔ bā luópèiyún lǐngdǎo tiān’é gēwǔ jù yì tuán èrshíwǔ rén zuó dǐ xīng èrshíjiǔ wǎn qǐ zài kuàilè shìjiè yǎnchū” 谢鲁八罗佩云领导 天鹅歌舞剧艺团 二十五人昨抵星 二十九晚起在快乐世界演出 [The 25 artistes from the Swan Song and Dance Troupe led by Tse Liu-Baat and Lo Pai Wan arrived in Singapore yesterday and will be performing on the stage of Happy World Stadium from May 29th], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 27 May 1956, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lo Pai Wan confirmed when she left and Liu’s exact date of departure during a phone interview with the author on 27 August 2018. ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, “Shídài qū” 时代曲 [Popular melodies], Nanyang Siang Pau Supplement 南洋商__报副刊, 16 May 1971, 7 (Microfilm NL6795) ↩

-

Liu “Shídài qū,” 16 August 1971. ↩

-

Published under Liu Yichang’s pseudonym, Ge Li Ge 葛里哥 and Chun Zhi 春治_was serialised in _Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报 from 12 to 25 January 1957: 12 Jan 1957, 8; 14 Jan 1957, 7; 15 Jan 1957, 8; 16 Jan 1957, 8; 17 Jan 1957, 7; 18 Jan 1957, 8; 19 Jan 1957, 14; 21 Jan 1957, 7; 22 Jan 1957, 8; 23 Jan 1957, 14; 24 Jan 1957, 8; 25 Jan 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Published under Liu Yichang’s pseudonym, Ling Hui Ling 令狐玲, 李太白捉月 [Li Bai Catching the Moon] was serialised in Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报 from 1, 3–4, 6–11 May 1957: 1 May 1957, 16; 3 May 1957, 14; 4 May 1957, 16; 6 May 1957, 8; 7 May 1957, 7; 8 May 1957, 14; 9 May 1957, 16; 10 May 1957, 14; 11 May 1957, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Yichang 刘以鬯, ed., Xiānggǎng duǎnpiān xiǎoshuō xuǎn (wǔshí niándài) 香港短篇小说选 (五十年代) [Selected Hong Kong short stories in the fifties] (n.p.: 天地图书有限公司出版, 1997), 2; Zheng Mingren 鄭明仁, “Liú yǐ chàng yǔ sān háo zǐ xiǎoshuō” 劉以鬯與三毫子小說 [Liu Yichang and His 30-Cent Pulp Novels], Ming Pao 明報, 26 October 2016. ↩

-

Liu, Re dai feng yu, 334. ↩

-

Chen, 26 Dec 2016. ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Liúlián gāo yǔ pixie” 榴莲糕与皮鞋 [Durian cake and leather shoes], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 11 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Wù luò zhī yè” 勿洛之夜 [Night at Bedok], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 26 May 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Xīn mǎ dàoshàng” 新马道上 [On the bus from Singapore to Malaysia], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 5 November 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Zài xīn lóng yè yóu chē shàng” 在新隆夜邮车上 [Night train from Singapore to KL], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 3 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Wǎn lǐfú” 晚礼服 [Evening dress], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 21 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Róufú láikè” 柔佛来客 [A visitor from Johor], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 6 October 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Bànyè chǎng” 半夜场 [Midnight show], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 24 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Mǎchǎng xǐjù” 马场喜剧 [A comedy at the racecourse], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 25 July 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Jiǔtú” 酒徒 [The drinker], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 21 April 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu, Re dai feng yu, 333–34. ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Shùnxī jílóngpō” 瞬息吉隆坡 [Kuala Lumpur at the blink of an eye], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 14 April 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Ā shěn” 阿嬸 [Ah Sum], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 20 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Yī shì mài” 伊士迈 [Ismail], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 4 August 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu, Re dai feng yu, 333–34. ↩

-

Liu, Re dai feng yu, 333–34. ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Niú chē shuǐ zhī chén” 牛车水之晨 [A morning in Kreta Ayer], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 10 March 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Yē lín qiǎngjié” 椰林抢劫 [Robbery in the coconut grove], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 15 January 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gé Lǐ Gē 葛里哥, “Lánbǎoshí (liú yǐ chàng bǐmíng)” 蓝宝石 (刘以鬯笔名) [Blue gemstone (Liu Yichang’s pseudonym)], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商__报, 8 December 1958, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Yichang, 刘以鬯, “Wǒ wèishéme xiě mǎ lái gūniáng” 我为什么写马来姑娘 [Why I have written Malay Girl], International Screen Magazine 国__际电影 no. 45 (July 1959): 10–11. ↩