The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in Singapore

When influenza hit Singapore in 1918, many were sickened, hospitals were overwhelmed and everyday life was disrupted.

By Sean Hoh

“Illness in Singapore”. “The Mysterious Malady”. “Disease Gradually Spreading in Singapore”. These are not newspaper reports on the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Instead, these are headlines that appeared over a century ago in local newspapers about the influenza pandemic, which gripped Singapore and the world in 1918.1

Between 1918 and 1919, the world was besieged by an influenza pandemic so deadly that approximately 1 in 20 died from the pandemic within the first two years. The illness affected more than 500 million people out of an estimated 1.8 billion world population.2

The disease was commonly known as the “Spanish flu”, although this term is a misnomer given that the virus did not originate from Spain. The first reported case of this strain of the influenza virus can be traced to a military base in Kansas in the United States in March 1918. However, news about the high infection rate of the influenza virus was suppressed in the countries that constituted the Allied Powers during World War I (1914–18), including the United States.3

In contrast, there was relatively greater freedom of the press in Spain during the war as it remained neutral. Consequently, the virus took on the name “Spanish flu” because Spain was one of the few countries that reported it.4

A Colony in Crisis

Like most of the world, Singapore was not spared the devastating effects of the virus outbreak. The influenza pandemic in Singapore was short but acute,5 and it took the lives of at least 2,780 individuals.6 The spread of the virus was rapid: it had arrived in Singapore with wartime troops in June 1918 and quickly spread throughout the Straits via maritime and land routes.7

After the first wave of the pandemic from June to July 1918, Singapore was hit again by a second wave from October to early November 1918. Thankfully, the outbreak was controlled by November 1918, unlike in other parts of the world that endured a recurrence of the disease in early 1919.8

One of the key reasons for the swift transmission of the influenza virus across Singapore was the unpreparedness of the British colonial administration. Responsibility for the control of infectious diseases was shared between the Straits Settlements government and the Municipal Commission. There had been established medical infrastructures such as quarantine camps and an epidemiological regime that covered the early detection of infectious diseases from foreign ports. However, influenza had not been included in the administration’s list of reportable contagious diseases during the early stages of the pandemic.9

This oversight can perhaps be attributed to a lack of understanding about the influenza virus at the time as well as the fact that the British were preoccupied with World War I. The colonial administration, therefore, missed early signs of the outbreak, which allowed the virus to spread rapidly throughout Singapore. Indeed, this ignorance about the virus in 1918 led to ineffectual governance. To address the outbreak, the Municipal Health Officer had suggested that patients simply rest in bed until they recovered.10

As the virus outbreak grew increasingly severe, there was a growing understanding of the virus, albeit on a limited scale. An article in the Chinese newspaper Lat Pau (Le Bao; 叻報) on 30 October 1918 warned against panic and the risk of misdiagnoses driven by fear of the influenza virus. By November 1918, the Royal College of Physicians in London publicly acknowledged that the virus was poorly understood and that no cure existed – a statement that was subsequently published in Singapore by the Municipal Commission.11

The unpreparedness of the colonial administration can also be seen in the disruptive impact that the pandemic had on Singapore’s healthcare centres: many hospitals and clinics were overwhelmed by the sheer number of infected patients who needed medical attention. For example, Tan Tock Seng Hospital had to hire six additional dressers to help staff manage the sudden surge in patients during the first wave of the pandemic.12

During the second wave, when the pandemic reached its height, the hospital had to erect a large temporary ward and hire a temporary assistant surgeon as the hospital saw 547 patient cases. Of these, 210 patients died, reflecting the severity of the outbreak. Similarly, the quarantine camp on Moulmein Road had to rapidly expand its capacity beyond the intended 172 beds to cope with the abrupt rise in the number of sick patients. The Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital set up by the Chinese community was also reported to have been filled with influenza patients.13

Exacerbating the predicament, staff in the hospitals also fell sick. For instance, 12 of the 19 nurses at the General Hospital fell ill concurrently, causing serious manpower constraints. Under these conditions and faced with a bed crunch, the hospital struggled to attend to patients suffering from influenza, which totalled 314 cases in 1918, many of whom were already seriously infected upon admission. Attempts to isolate these patients from other patients were futile: the virus spread rapidly throughout the hospital, leading to deaths from resulting complications.14 Indeed, nearly all healthcare centres in the colony faced enormous strain.

The Straits Echo attributed the “abnormal death rate” to the perceived incompetence of healthcare professionals. The paper observed that the Medical Department was “too short-handed in doctors” and mockingly wrote: “There used to be a belief that the cure for an abnormal death rate was for the senior medical officer of the Municipality to go on leave, and immediately the death rate fell. On his return there was full work in an increasing death rate.” As healthcare providers struggled with overcrowding and understaffing, the colonial administration eventually had to depend on supplementary support in the form of private or consolidated community efforts.15

By the second wave of the pandemic in October 1918, the colonial administration realised the severity of the disease and introduced a series of hygiene measures to contain the spread of the virus. Little was still known about the virus, but the widespread infections and deaths had become undeniably apparent. The administration increased the frequency with which the streets in Singapore were washed, incurring “an average $400 a day on disinfectants”.16

The infected were advised to self-isolate, while the public was cautioned to avoid crowded places. “Command orders” were also published, which included instructions on how to disinfect the nose and throat. Additionally, at the orders of the Principal Civil Medical Officer, hospital visits were regulated through special permits that only “friends of patients [of the] seriously ill” could obtain.17

Gradually, after the introduction of these measures, the pandemic subsided in Singapore. While the second wave was severe, it did not persist over an extended duration. According to newspaper reports, many previously infected individuals had returned to work by 28 October 1918. And by the following month, the pandemic was over in Singapore. In fact, Singapore somehow managed to evade a third wave of the influenza, which had spread to most temperate countries by early 1919.18

In November 1919, the colonial administration introduced more stringent measures to better prepare for another pandemic. For instance, an amendment to the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance (Ordinance 34 of 1919) states: “The Health Officer of the district may detain any person who is found… to be suffering from an infectious disease… until such a time as the disease is no longer communicable to other people.” Evidently, the 1918 pandemic had cast a dark shadow over Singapore’s early medical history.19

Living with the Pandemic

The pandemic was a time of worry, frustration and confusion for many who resided in Singapore. From their perspective, the colonial administration’s actions appeared to be lacking and they shared their views in the local newspapers. On 24 October 1918, a reader of the Straits Times, who went by the pseudonym, “A Patient Sufferer”, wrote: “Would you kindly permit me… to draw the attention of our City Fathers to the present disgraceful condition of the River Valley and Oxley Roads. The dust being allowed to accumulate on them is several inches deep.” He added: “[W]hen the Spanish ‘Flu’ is making such heavy inroads on the health of our population, the consequences arising by the air being thickened by the germ-producing dust are so potent that it is not necessary to over-draw the picture.”20

Two days later, another reader who used the moniker, “Another Sufferer”, added his comments to the earlier letter. “May I add my quota to the remarks of ‘Patient Sufferer’ on the hideously dusty condition of River Valley and Oxley roads. I do not think these roads have been watered this year – except by rain. They are of laterite or laterite mixed, and the clouds of dust are appalling, and daily one may see a diligent road-sweeper sweeping up clouds of this dust which pours into the houses alongside.”21

Another cause for concern among the people was that public spaces in Singapore could facilitate the spread of the influenza virus (places that we now refer to as “virus hotspots”). On 17 October 1918, a Straits Times reader questioned why the colonial administration had not closed schools in Singapore and asserted that the administration should be proactive in closing schools instead of waiting for cases to be reported among students before reacting.

“We have all seen the warnings issued indirectly by the Legislative Council and directly by the Municipality regarding the present influenza epidemic, but it must be confessed that very little assistance is to be obtained therefrom in preventing the spread of the disease… the authorities might move first and do what would be obvious to any ordinary layman, and that is to immediately close all the schools.” The writer added that “the daily close association of scholars is an ideal way to spread infection over a wide area in the least possible space of time”.22 Following this, schools in Singapore were closed by 22 October 1918,23 while theatres and cinemas did the same by 23 October.24

The pandemic affected different communities in vastly different ways. The Europeans lived mainly in the town area, led privileged lives and therefore experienced low death rates, while communities that lived in rural kampongs (villages) suffered greatly as they saw far higher fatalities than those living in urban areas. Indians, especially migrant workers, endured much hardship and were hardest hit by the virus outbreak. This led to the ignorant belief that Indians harboured a “racial weakness” which rendered them more vulnerable to diseases.25

Among the Chinese, there was a general resistance to Western medicine and the edicts of the colonial administration. This is evidenced by complaints that the Chinese flouted the hygiene measures imposed by the administration.26

The Municipal Commission published notices advising infected patients to self-isolate, which the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce translated into Chinese. However, the framing of these precautions through the lens of Western medicine alienated the Chinese. Consequently, the Chinese sought alternative cures such as a mixture of boiled pumpkins, potatoes and coriander leaves, which became so popular that the price of potatoes rose due to the surge in demand. Many Chinese coolies, who lived mainly in cramped and poorly ventilated shophouses, also succumbed to the virus as the unsanitary living conditions enabled it to spread more easily.27

Businesses were also heavily disrupted in Singapore. “Work in Government offices and in mercantile firms is being handicapped through a shortage of assistants, especially the Chinese,” reported the Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle on 5 July 1918. As the first wave of the influenza epidemic took its toll, the Post Office put up a notice that it was “necessary to curtail somewhat the postal deliveries in town and suburban areas” and “there will, unfortunately, be some delays” due to “a great deal of sickness among the postal employees”. Similarly, there was a “disturbance [to the] normal efficiency” of telephone services as the epidemic had “hit the staff of the Telephone Company very hard”. Socialising became a challenge as well because interactions inadvertently risked the transmission of the virus.28

Perhaps most sobering of all were accounts that corpses on the street and funerals had become a part of everyday life in Singapore during the pandemic.29 Obituaries dedicated to individuals who had lost their lives to influenza became common.

The Pandemic and Falsehoods

The chaos of the pandemic was exacerbated by misinformation and disinformation that spread throughout Singapore with a virulence akin to that of the influenza virus. There was much speculation about the virus which created an air of paranoia throughout the pandemic. Some of these falsehoods were even printed in the local newspapers.

An article in the Straits Times on 18 June 1918 linked the virus outbreak to “the irregularity of the weather”.30 On 27 July 1918, another article blamed the viral outbreak on the durian: “It is said that the illness is brought about by eating ‘durian’ fruit, but, strangely enough, it does not appear to affect Chinese or Malays.”31

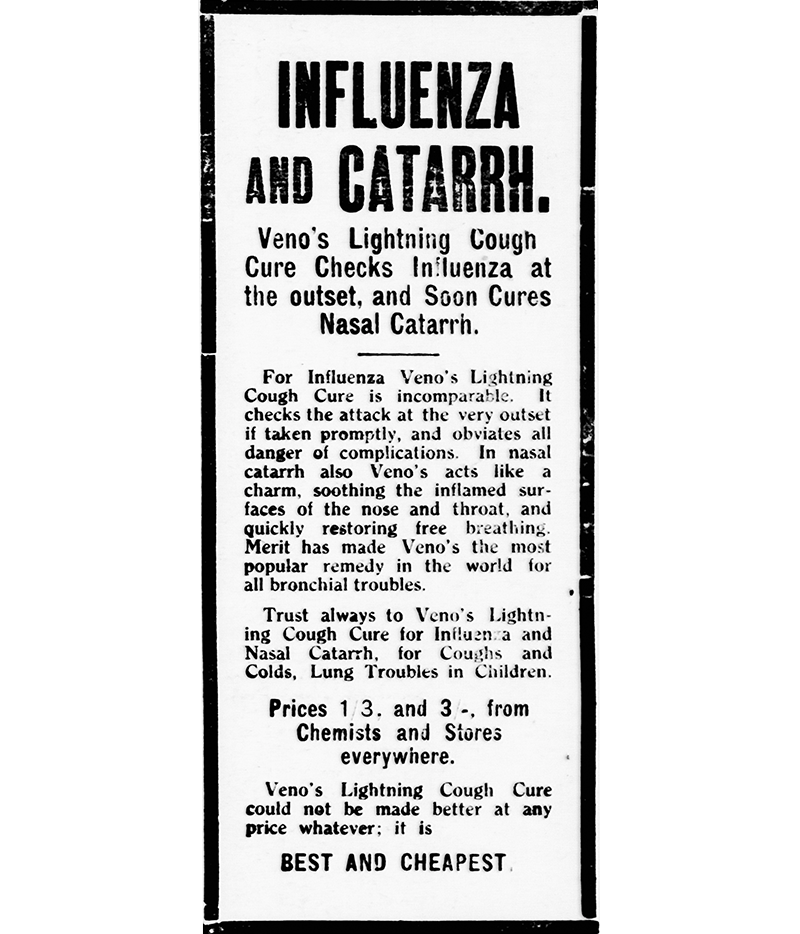

Opportunistic companies took advantage of the widespread fear and uncertainty among the people to frame their products as cures for symptoms of influenza and related illnesses in newspaper advertisements. Prior to the pandemic, Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure had only been marketed as a remedy for coughs. However, an advertisement in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 6 November 1918 proclaimed that “Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure Checks Influenza at the outset”.32

Remembering the “Forgotten Pandemic”

A little more than a century has gone by since the 1918 influenza pandemic in Singapore. Since then, the virus outbreak has largely been forgotten in public memory as it occurred in the shadow of World War I.

But there has been some revival of interest in the 1918 influenza pandemic due to subsequent outbreaks throughout the 20th century – the latest being Covid-19 that emerged in December 2019 – that were reminiscent of it.

Comparing the two pandemics, about 100 years apart, is instructive. Unlike the case with the 1918 pandemic, the Singapore government was more prepared to combat Covid-19 in 2020. Drawing lessons from previous outbreaks of infectious diseases, especially SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2003, the government immediately set up a Multi-Ministry Taskforce by January 2020 to tackle the outbreak.33 The preparedness of the government allowed it to react nimbly to the outbreak, ensuring that necessary hygiene measures such as social distancing and testing were evenly, efficiently and effectively put in place.

Moreover, medical knowledge and public health infrastructure had significantly advanced in the century since the 1918 pandemic. As a result, the epidemiological characteristics of the novel coronavirus were rapidly identified in 2020, and accurate information was efficiently disseminated to the public in Singapore.34 Greater scientific clarity enabled timely and appropriate public health measures to be implemented, in contrast to the 1918 pandemic, during which limited understanding led to ineffective or misguided treatments.

Crucially, effective therapies were developed more quickly in 2020 compared to 1918. While the influenza vaccine was developed long after the 1918 outbreak, the first Covid-19 vaccines were ready for distribution in Singapore by December 2020.35

While the 1918 influenza pandemic was met with uncertainty and unpreparedness, the Covid-19 outbreak was met with swift action, clear communication and groundbreaking medical innovation. This contrast highlights the significant progress in public health made in the last 100 years and also the vital importance of learning from history.

Notes

-

“Illness in Singapore,” Straits Times, 3 July 1918, 7; “The Mysterious Malady,” Straits Times, 9 July 1918, 8; “Disease Gradually Spreading in Singapore,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 24 October 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kenny Abdo, Spanish Flu (Minnesota: Abdo Zoom, 2021), 19. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 614.5 ABD); John M. Berry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 397. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Antoni Trilla, Guillem Trilla and Carolyn Daer, “The 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ in Spain,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 47, no. 5 (September 2008): 668. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); National Library Board, “The Spanish Flu,” last updated 29 July 2025. (From Reference@NLB); Michael A. Vance, “Disease Mongering and the Fear of Pandemic Influenza,” International Journal of Health Services 41, no. 1 (2011): 102. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Trilla, Trilla and Daer, “The 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ in Spain,” 668–69; Abdo, Spanish Flu, 14. ↩

-

“Negri Sembilan Notes,” The Singapore Diocesan Magazine: A Quarterly Record of Church Work 9–10, nos. 33–40 (November 1918–November 1920): 36. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Vernon J. Lee et al., “Influenza Pandemics in Singapore, A Tropical, Globally Connected City,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 13, no. 7 (July 2007): 1054, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18214178/. ↩

-

Prema-chandra Athukorala and Chaturica Athukorala, The 1918–20 Influenza Pandemic: A Retrospective in the Time of COVID-19 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 9, https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/191820-influenza-pandemic/E2695A213FACA1CD66D1AC9144EE7FD1. ↩

-

Lee et al., “Influenza Pandemics in Singapore,” 1052–53. ↩

-

Kah Seng Loh and Li Yang Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 1819–2022: Lessons for the Age of Covid-19 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2024), 154. (From NLB OverDrive); Liew Kai Khiun, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short: The Episode of the 1918 Influenza in British Malaya,” Modern Asian Studies 41, no. 2 (March 2007): 239. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Lee et al., “Influenza Pandemics in Singapore,” 1055; Olivia Ho, “How the Straits Times Covered Past Pandemics,” Straits Times, 19 April 2020, B6. (From NewspaperSG); Loh and Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 160. ↩

-

“Yi zai jing you fei liuxingbing er zuo liuxing bing yizhi zhe” 異哉竟有非流行病而作流行病醫治者 [It is strange that non-influenza cases are being treated as influenza], Lat Pau 叻報, 30 October 1918, 3, NUS Libraries, https://oa.nus.libnova.com/view/436041; Loh and Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 160. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Medical Department, Straits Settlements Medical Report 1918 (Singapore: Straits Settlement Medical Department, 1918), 22, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/etgw9ggs. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Medical Department, Straits Settlements Medical Report 1918, 22; Loh and Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 154, 162; “The Road to Pandemic Preparedness in Singapore,” National Centre of Infectious Diseases, accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.ncid.sg/For-General-Public/Pages/The-NCID-Gallery.aspx. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 28 October 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Loh and Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 160–62. ↩

-

“Random Notes,” Straits Echo, 30 July 1918, 4. (From NewspaperSG); Liew, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short,” 223. ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Straits Echo, 30 October 1918, 8. (NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liew, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short,” 242; Lee et al., “Influenza Pandemics in Singapore,” 1055; “Influenza Precautions,” Straits Times, 6 November 1918, 8; “Visitors to the Hospital,” Straits Times, 19 October 1918, 8. (NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Influenza Epidemic,” Malaya Tribune, 28 October 1918, 4. (From NewspaperSG); Vernon J. Lee et al., “Twentieth Century Influenza Pandemics in Singapore,” Academy of Medicine, Singapore 37, no. 6 (June 2008): 471, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18618058/; Lee et al., “Influenza Pandemics in Singapore,” 1053. ↩

-

“An Ordinance to Amend the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance, 1915 (No. 34 of 1919),” 27 October 1919, Ordinances enacted by the Governor of the Straits Settlements with the Advice and Consent of the Legislative Council Thereof in the Year 1916–1919 (Singapore: Printed at the G.P.O., 1916–19). (From National Library Online) ↩

-

A Patient Sufferer, “Influenza,” Straits Times, 24 October 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Another Sufferer, “River Valley Road Dust,” Straits Times, 26 October 1918, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Prophylactic, “Influenza,” Straits Times, 17 October 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Influenza Epidemic,” Straits Times, 22 October 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Influenza,” Straits Echo (Mail Edition), 23 October, 1918, 1630. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liew, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short,” 235–36, 251. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 25 October 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Loh and Hsu, Pandemics in Singapore, 160, 163–64; Liew, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short,” 247. ↩

-

“Illness in Singapore,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 5 July 1918, 3; “Telephones and Influenza,” Straits Times, 23 October 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG); “Liuxing bing zhi wan e” 流行病之萬惡 [The evils of the epidemics], Lat Pau 叻報, 1 November 1918, 3, NUS Libraries, https://oa.nus.libnova.com/view/436045. ↩

-

Liew, “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short,” 222. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 18 June 1918, 6. (From Newspaper SG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 17 July 1918, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 2 Advertisements Column 3,” Straits Echo, 7 November 1916, 2; “Page 5 Advertisements Column 1,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 8 February 1917, 5; “Page 7 Advertisements Column 5,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 6 November 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ministerial Statement on Whole‑of‑Government Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019‑nCoV),” Ministry of Health (Singapore), 3 February 2020, https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/ministerial-statement-on-whole-of-government-response-to-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-%282019-ncov%29. ↩

-

“Minsterial Statement on Whole‑of‑Government Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019‑nCoV).” ↩

-

Yuen Sin, “Covid-19 Vaccination Drive Kicks off with Jabs for 40 NCID Healthcare Workers,” Straits Times, 30 December 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/coronavirus-vaccination-drive-kicks-off-to-pave-way-for-more-economic-activities. ↩