How Tay Seow Huah Came to Be the First Spy Chief of Independent Singapore

In a BiblioAsia+ podcast episode, Simon Tay – lawyer, academic and winner of the 2010 Singapore Literature Prize – tells us how his Penang-born father came to play a giant role serving a newly independent Singapore.

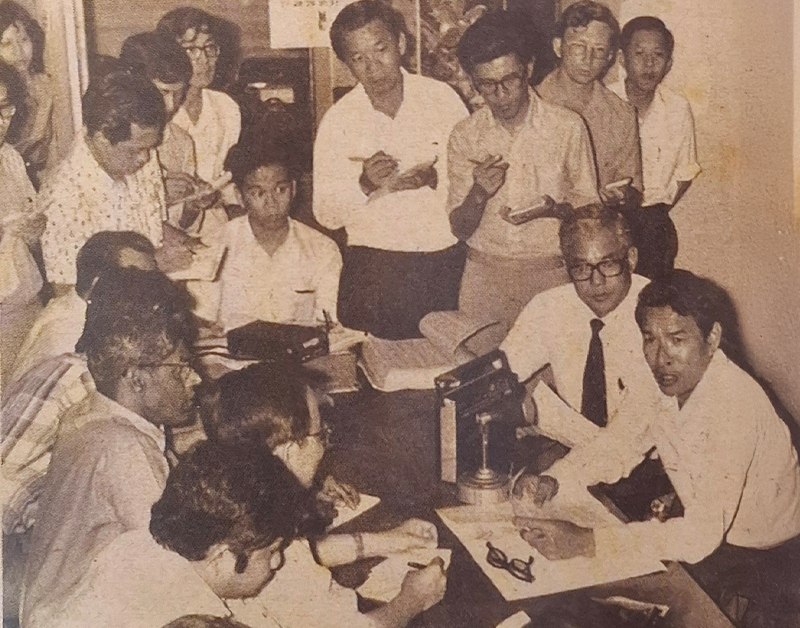

Tay Seow Huah, then Permanent Secretary for the Ministry of Home Affairs, helmed Singapore’s response to the 1974 Laju hijacking. This was when four terrorists tried (but failed) to destroy Shell’s oil infrastructure on Pulau Bukom Besar and subsequently took five hostages.

Little is known about Tay, who was the founding Director of the Security and Intelligence Division. BiblioAsia Editor-in-Chief Jimmy Yap interviews Tay’s son Simon, who has written a memoir about his father titled Enigmas: Tay Seow Huah, My Father, Singapore’s Pioneer Spy Chief.

Simon Tay: My father in 1965 got a call from Mr Lee Kuan Yew at the helm of the newly independent republic, and basically got told to head the Special Branch. Why him? Well, prior to this, he was the port manager at the Singapore Harbour Board, today the Maritime & Port Authority [of Singapore] and in between that, the Port Authority of Singapore.

How did a port manager in charge of human resources get entrusted by Mr Lee to head the Special Branch? And that’s where a lot of the writing about [my father’s] pre-Laju career began, and where I have to sort of delve and in a way speculate. One of the speculations was that he was involved in politics of the highest order. At that time, the port and the unions were riddled with leftists, and there was huge tension. A strike or closure of the port would have been ruinous for Singapore.

Jimmy: Right.

Simon: The port is in the ward of Tanjong Pagar, which is the heart of Lee Kuan Yew’s constituency. When Mr Lee met the Port Union workers, the only civil servant in the room as far as the records show, was my father. I think that trust in handling highly politically dangerous situations grew between Mr Lee and my civil servant father. My father was not a politician. And then when this Special Branch evolved, my father was entrusted to split the Special Branch into two parts. The Security Services Division (in charge of external issues) and the Internal Security Division (to deal with internal issues) at that time were under a single ministry, the Ministry of Interior and Defence. And my father, therefore, headed both agencies.

I think that gave a lot of background to his experience as being, as the title of the book suggests, the pioneer spy chief of Singapore. And so in 1974, he was the man that Mr Lee called.

Jimmy: What struck me was the youth of all the main protagonists: Mr Lee and your father. How old was your father at the time?

Simon: He was 41. The founding generation was thrown into the deep end, right? They had to make Singapore succeed, or there would be no turning back. And my father felt this strongly because he had come down to Singapore for university. He was actually born in the north of Malaya. And he had a choice, I guess, of joining Malaysia or Singapore, but he opted to be here. They were awfully brave because they really had not many choices.

Jimmy: Your account of the hostage situation your father was dealing with was very detailed. I was just reading Mr [S.R.] Nathan’s biography, and he has some information. Presumably the press would have covered what they could see and what they were told. I always felt like you had an insight into what he [Tay Seow Huah] was doing in that office in Kallang. I’m sure the security agency wasn’t anxious to open their file for you.

Simon: There is a lot of information, but the information on Laju is scattered and sometimes needs to be reconciled. So Mr Nathan’s book was a good resource for me. I knew Mr Nathan when I was a child. My father and he were friends from the first years of civil service. When I grew up, I called him Uncle Nathan. And I would ask his family and speak to his son, who’s about my age, about what he could remember.

And Mr Nathan’s book went into great detail. Of course, the newspapers covered it. And not just the Singapore newspapers and the New York Times, but also Japan’s side because the Japanese terrorists who were in the Red Army were involved. And of course, the archives [National Archives of Singapore] had the transcripts of all the press statements.

Jimmy: We know that President Nathan was part of a team of Singaporeans who accompanied the four hijackers to Kuwait to guarantee their safety. And I think your father was or was perhaps possibly one of those people who was supposed to have gone on, but didn’t. In your book, you talked about that.