The 1965 Singapore Agricultural Show

Initially planned to encourage people to eat more eggs, the agricultural show eventually morphed into a mega event showcasing the achievements of farmers in Singapore.

By Caleb Leow

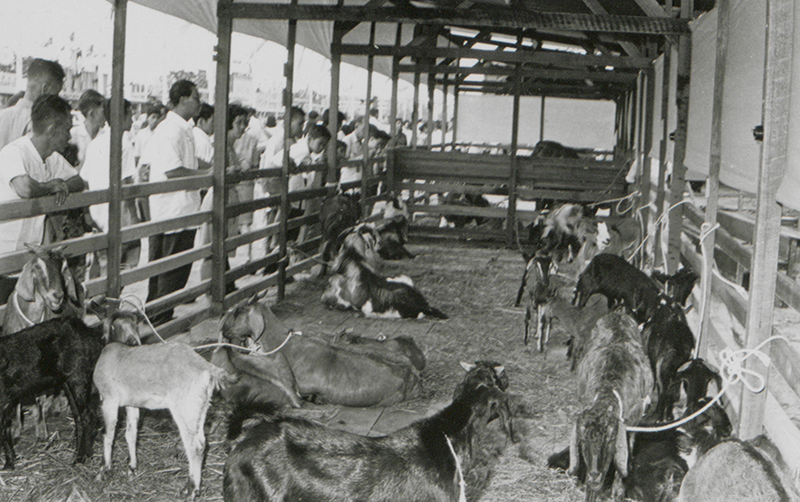

For just over a week in 1965, the heart of Singapore was filled with the sounds of grunting, mooing, bleating, gobbling, clucking and quacking. This is because some 13 stalls – filled with pigs, cows, goats, turkeys, chickens and ducks – had been set up in Kallang Park (where the Singapore Sports Hub now sits) for the Singapore Agricultural Show. Hundreds of thousands of curious city-dwellers made their way to the public park from 18 to 26 September to take in the sights and admire the vegetables, flowers and fruits – all locally produced – on display.1

In his speech at the opening of the event on 19 September, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew acknowledged that the idea of an agricultural show in Singapore had an air of improbability. “I would like to say that there is a little bit of the flair for greatness when we call this an agricultural show,” he said. Yet what the show had achieved was something to be proud of, he noted. “You know, for an island of 214 square miles at low tide, and at high tide perhaps, two square miles less, to talk of agriculture is to take a deep breath and spread one’s chest out, and I think that is what Singapore has been doing.”2

The farm show shone a spotlight on Singapore’s rural sector, which had taken on newfound importance in the immediate wake of independence just a month prior. The show’s abundant display of livestock and fresh produce seemed to represent, at a vulnerable historical moment, a budding nation’s potential to survive and thrive. Although its timing was fortuitous, the event had been months in the making and had been set in motion by something far more quotidian than a desire to demonstrate strength. It all started because Singapore had too many eggs.

Hatching a Plan

On 21 March 1965, the Straits Times reported that an egg glut “had resulted in a drop of farm price from about 8½ cents to 6½ cents an egg”. Coupled with the increased price of chicken feed, the decrease in profits placed a strain on the livelihood of some 150,000 farmers in the livestock industry.3

Ho Seng Choon, an egg farmer who became one of the organisers of the agricultural show, turned to the Primary Production Department (PPD) for help. The department had been formed in 1959 under the Ministry of National Development to work closely with farmers to promote the interests of rural industry. The PPD decided that the egg farmers needed assistance. “While we encourage exports of eggs, we will also launch a campaign to encourage local people to eat more eggs,” said Cheng Tong Fatt, the director of the PPD. “This will be carried out through the Press, radio, television, schools and exhibitions.”4

The 1965 egg glut led to the formation of a 20-man action committee comprising personnel from the PPD and two farmer organisations – the Singapore Stockfeed Manufacturers’ Association (饲料商公会) and the Singapore Livestock Farmers’ Association (禽畜业协会).5 These two associations would work closely with the PPD to organise the campaign later in the year.

Although the egg glut crisis eventually improved, the organisers still went ahead with the plan to organise a campaign and Ho began to devise new ways to promote local agriculture. “[The egg crisis] had stabilised, but we couldn’t stop there, we needed to find new ways to go further, to showcase the development of farming in Singapore,” he said (“这个问题稳定下来,稳定下来我们不能够停在那边,我们要想办法推动,表现我们新加坡的农业发展”).6

This led to the idea of a large-scale agricultural show mooted by Ho and another farmer, Ng Hung Theng. The duo said in jest that each of them would require $50,000, a sum Cheng was in fact open to providing. He even offered to deploy the full PPD team of 21 personnel to help when Ho claimed that an event of such a scale would be impossible to manage alone. It was thus only with the support of the PPD that the agricultural show managed to reach the impressive scale it did, costing almost $100,000 in the end, the precise amount promised by Cheng to the two farmers.7

As the project grew in scope, it attracted the attention of the prime minister. In his oral history interview, Ho recounted the anecdote of Lee turning down the invitation to open the show, assuming that it would be a small-scale event requiring, at most, the presence of a high-ranking minister (“他认为小规模的东西,最好你放一个高级政府官员就好”). However, unbeknownst to Ho and the other organisers, Lee eventually went to check out the progress of the event, and he was so impressed that he decided to open the show himself (“后来我们做好了,不懂他自己跑去看,看了以后,打电话到局长那边去,要放他的名,他要去剪彩,所以那天他去剪彩”).8

A Feast for the Eyes

The highlight of the show was a display by 526 farmers over 13 stalls. There were six stalls for pigs, cattle and goats, three for poultry, ducks and eggs, while the remaining four displayed vegetables, flowers and fruits. These were not only exhibited for the public but were also part of a competition. The farmers who showcased the best “eggs, fowls, ducks, geese, pigs, goats, cattle, flowers, vegetables, fruits, singing birds and aquarium fish” stood to win a total of $20,000 in cash, as well as other prizes such as modern farming equipment, implements, animal feed, fertilisers, pesticides and veterinary drugs.9

The agricultural show was only one of the attractions of the event. Variety shows were staged at the far end of the park, near the seafront, while Chinese wayang (operas) were performed on a smaller stage nearby. Other forms of entertainment included band performances, a mini zoo, an amusement park for children, a Chinese riddle competition and even a Chinese chess competition. Visitors also participated in a lucky dip. There were vegetables, fruits, eggs and poultry sold at lower prices, and hawker stalls and restaurants offering special dishes and delicacies.10

The agricultural show turned out to be a crowd pleaser. Over the course of nine days, it drew a total of some 300,000 visitors.11 In the Sin Chew Jit Poh newspaper, a visitor by the name of Wu She wrote: “While exhibitions are a regular feature in Singapore, this agricultural show was in a whole different league” (“在星洲经常都有展览会的举行,但这个农展会是别开生面的了”).12 Another visitor, Jia Ling, described how different generations of visitors clustered around different activities: “Elderly folk were so engrossed in the Chinese operas that they forgot about the many other stalls they had yet to visit, youngsters were enraptured by the frenetic music, while kids snuck off to squat under the silver screen” (“老人家看 [古装] 大戏看得入神忘记了后头还有许多没看完的摊位;年轻人被疯狂的音乐迷住了;小孩子却溜到银幕下蹲了下去”).13

Beyond just entertaining the public, one of the objectives of the event was to draw attention to the close ties between the PPD and farmers. “My department is intensifying the drive to promote better and more modern agriculture with the help of the two associations to step up production,” said Cheng. “Furthermore, many new industries have been established to produce animal feeds, fertilisers and veterinary drugs, and many more are expected to be formed to produce agricultural equipment and implements and allied products deriving their raw materials from agriculture.”14

Across the stalls of livestock and fresh produce were sheds housing “tractors and other types of machinery, gardening tools, animal feeds, fertilisers, pesticides, veterinary drugs, seeds, hatcheries and other equipment”, giving farmers the chance to be exposed to the latest technology and farming equipment. Exhibition booths were also set up by the PPD and the Urban and Rural Services Committee to showcase the work done by the government in improving the lives of the rural population, while nightly screenings at the entrance of the park highlighted the PPD’s role in helping farmers produce better crops, livestock and poultry.15

Since the creation of the PPD in 1959, the department had been working closely with farmers to improve their livelihood via a range of free and subsidised services. A ploughing service introduced at the end of 1959 charged $20 per acre on a non-profit basis, while an experimental plant protection service was launched in October 1961 to combat pests and crop diseases. The PPD also provided demonstrations on the correct use of modern insecticides and fungicides as well as produced improved breeds of pigs and poultry which were then sold to farmers at low prices. As a result, pig production in 1964 increased by 14 percent, ducks by 50 percent, eggs by 20 percent and vegetables by 2.5 percent over the previous year.16

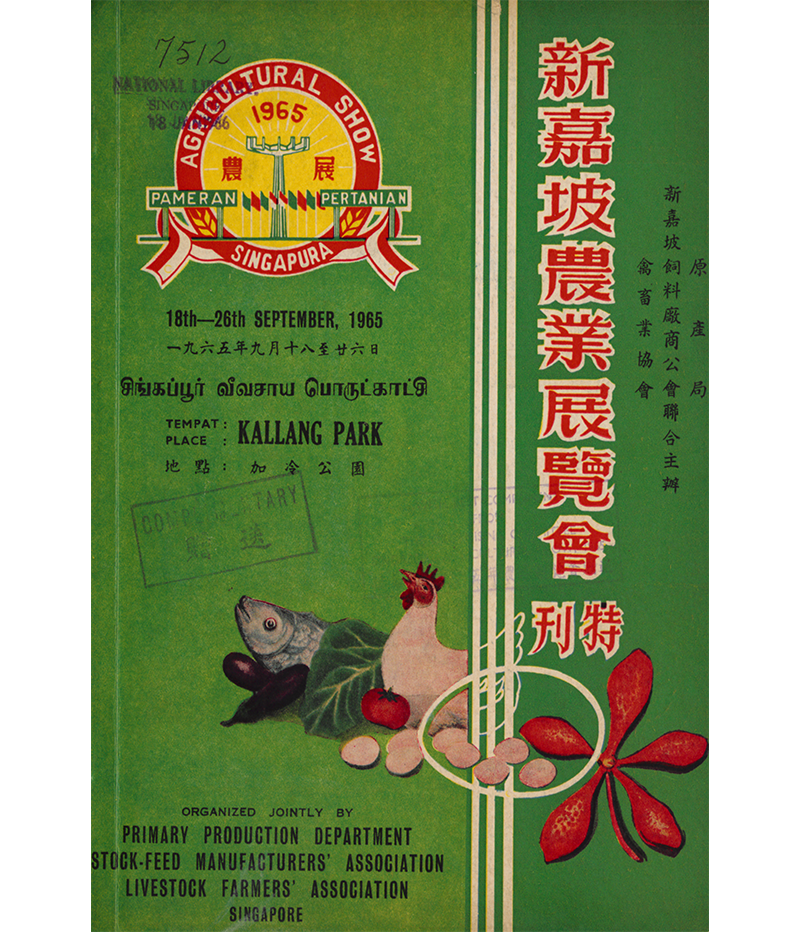

To commemorate the occasion, the organising committee produced a special publication for the show titled《新嘉坡农业展览会特刊》(Special Issue of the Singapore Agricultural Exhibition), which included messages from members of the organising committee, articles on recent innovations in farming, and advertisements by local feed companies, trading companies and international pharmaceutical companies.17

Cultivating Ties

In addition to showcasing Singapore’s farming sector, the agricultural show also had another dimension: it was an effort to placate the rural population who had become unhappy following the government’s resettlement of farmers and squatters in rural areas. The resettlement had begun in 1955 to make space for the development of Queenstown public housing estate, Singapore’s first satellite town. These efforts intensified from the early 1960s onwards, after Singapore was granted full internal self-governance, with the establishment of the Housing & Development Board (HDB) in 1960.18

Just a year later, clearance and resettlement began for the development of Singapore’s second satellite town, Toa Payoh, which was met with resistance from the ground.19 In a 1997 oral history interview, Alan Choe, the first architect-planner of the HDB, noted the unpopularity of such measures due to the disruption it caused to farmers. “Resettlement was a big problem because we are moving… even in the case of Toa Payoh, we are moving into an area where Toa Payoh had farms. Can you imagine a family that is doing farming for many many years, living off the ground, suddenly you go in and you tell them, ‘Look I want to take over your land, I want to do public housing and in return I am going to pay you compensation’.”20

Such rural unrest was alluded to by Minister for National Development Lim Kim San during his speech at a news conference in November 1964 announcing the commencement of work for the Toa Payoh satellite town. Lim blamed the postponement of the project on “the organised resistance mounted by the anti-nationalist pro-Communist group, who instigated the peaceful squatters in Toa Payoh to resist clearance work in this area for almost two years”.21

In a speech delivered at a prize-giving ceremony on 27 September 1965 for the winners of the show’s competitions, the Parliamentary Secretary for the Ministry of National Development, Ho Cheng Choon, took the opportunity to highlight how the success of the show “demonstrated that the farmers and rural people were not forgotten by the Government”. He added that it would “remove the grounds on which the pro-Communist anti-national elements have been accusing the Government of neglecting the rural people and the farmers.” He also pointed out that if the government had not worked together with the rural population, there would not be so many exhibits on display at the show, and that surplus poultry, pigs and eggs would not be exported to Malaysia and neighbouring countries.22

In a message published by the Straits Times on 19 September 1965, Minister for Law and National Development E.W. Barker also praised the show’s success which, in his words, served as an “eloquent refutation of the lies that have been spread by pro-Communist agitators who have been trying to deceive the rural residents into believing that they are being ill-treated by the Singapore government”. The agricultural show highlighted the achievements and success brought about by the hard work of both the farming population and the government, he said. Efforts by the government included the “provision of extension services, assistance and advice, with a view to increasing the productivity of our farming community, bringing down the cost of production and generally improving the standard of living of the rural residents”.23

A Fleeting Bloom

The success of the show led Ho to say that “exhibitions of this nature should be held periodically”. However, newspaper records seem to indicate that this was the last show of its kind to be organised. A two-day agricultural show was held in Choa Chu Kang in August 1966, but it was on a much smaller scale and did not receive the same kind of national attention as the 1965 show.24

In the years that followed, agriculture increasingly faded from the national consciousness as a result of industrialisation and urbanisation. The land available for farms was reduced from 14,000 ha in the 1960s to about 8,400 ha in the 1970s.25 Eventually, Singapore’s rural population was resettled into new HDB housing estates.

The process of urbanisation would only intensify over the next half century. Given Singapore’s small size, the ease of importing food, and the declining importance of agriculture to the economy compared to other sectors, it appeared that farming did not have a bright future. However, in 2019, the government announced a push to develop the country’s agri-food sector. It set a “30 by 30” goal to domestically produce 30 percent of the country’s nutritional needs by 2030. This move was a response to possible resource scarcity resulting from climate change.26

This goal has since been scaled down. In November 2025, a more modest target was revealed: to produce 20 percent of Singapore’s fibre consumption needs and 30 percent of its protein consumption needs by 2035. (In 2024, about 8 percent of fibre and 26 percent of protein consumed in Singapore were produced domestically, reported the Straits Times.)27

These new targets were announced after a year-long review of the original “30 by 30” goal. “We acknowledged that this was a challenging aspiration given our small and under-developed agri-food sector, our limited land resources and high operating cost environment,” said Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu at the opening of the Asia-Pacific Agri-Food Innovation Summit on 4 November 2025.28

The reduced targets reflect both a recognition of the challenges facing the agri-food sector as well as Singapore’s determination to work towards some measure of food self-sufficiency. As both the importance and difficulties of developing agriculture in Singapore are making the news again, it is perhaps high time to pay tribute to the contributions and achievements of Singapore’s early farmers.

Notes

-

“Rural People ‘Not Forgotten’: Ho,” Straits Times, 27 September 1965, 4; “Big Farm Show Opens in Kallang Park,” Straits Times, 19 September 1965, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Opening of the Agricultural Show at the Kallang Park in the Evening,” speech, Kallang Park, 19 September 1965, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. lky19670511) ↩

-

“Singapore’s Big Egg Crisis,” Straits Times, 21 March 1965, 11; “270,000 Eggs for HK,” Straits Times, 27 March 1965, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ho Seng Choon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 1 July 1994, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001519), 1–12; “Singapore’s Big Egg Crisis.” ↩

-

“Mammoth Agriculture Exhibition at Kallang Park,” Straits Times, 7 September 1965, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wu She 吳舍, “Canguan nongye zhan lan hui” 参观农业展览会 [Visit to the agricultural show], 星洲日报 Sin Chew Jit Poh, 25 September 1965, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jia Ling 嘉陵, “Nongye zhan lan hui suxie” 农业展览会速写 [Sketch of the Agricultural Show], 星洲日报 Sin Chew Jit Poh, 27 September 1965, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Never So Good Down on the Farm,” Straits Times, 3 June 1963, 5; “Big Farm Show Opens in Kallang Park.” ↩

-

Xin jia po nongye zhan lan hui tekan 新嘉坡农业展览会特刊 [Special Issue of the Singapore Agricultural Show] (Singapore: Primary Production Department, 1965). (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Kwek Sian Choo, Jean Chia and Gregory Lee, eds., Resettling Communities: Creating Space for Nation-Building (Singapore: Centre for Liveable Cities, 2019), 27, 116. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 333.1095957 KWE) ↩

-

Kwek, Chia and Lee, Resettling Communities: Creating Space for Nation-Building, 62. ↩

-

Alan Choe Fook Cheong, oral history interview by Soh Eng Khim, 20 May 1997, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 18, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001891), 9. ↩

-

“Work to Start Now on $150M. Satellite Town,” Straits Times, 27 November 1964, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Minister: We Can Forge Ahead to a Better Life for All,” Straits Times, 19 September 1965, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Big Farm Show Opens in Kallang Park”; “Singapore Farmers to Put on Two-Day Show,” Straits Times, 2 August 1966, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Choo Ruizhi, “Of Change & Challenges: Reminders from Singapore’s Past Agricultural Transformations,” Food for Thought, 12 October 2022, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-for-thought/article/detail/of-change-challenges-reminders-from-singapore-s-past-agricultural-transformations. ↩

-

Chang Ai-Lien, “Parliament: Big Push to Grow Singapore’s Food and Water Resources to Ensure Survival in the Face of Climate Change,” Straits Times, 7 March 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-food-and-water-challenges-from-climate-change-may-be-meat-and-drink-to-spore. ↩

-

Shabana Begum, “Singapore Drops ‘30 by 30’ Farming Goal, Sets Revised Targets for Fibre and Protein by 2035,” Straits Times, 4 November 2025, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/singapores-30-by-30-farming-goal-pushed-back-to-2035-with-revised-targets-for-fibre-and-protein. ↩

-

Begum, “Singapore Drops ‘30 by 30’ Farming Goal, Sets Revised Targets for Fibre and Protein by 2035.” ↩