Got Milk? The School Milk Scheme in Singapore

In the 1970s and 1980s, primary school children were encouraged to drink milk in school until the initiative curdled in the late 1980s.

By Rebecca Tan

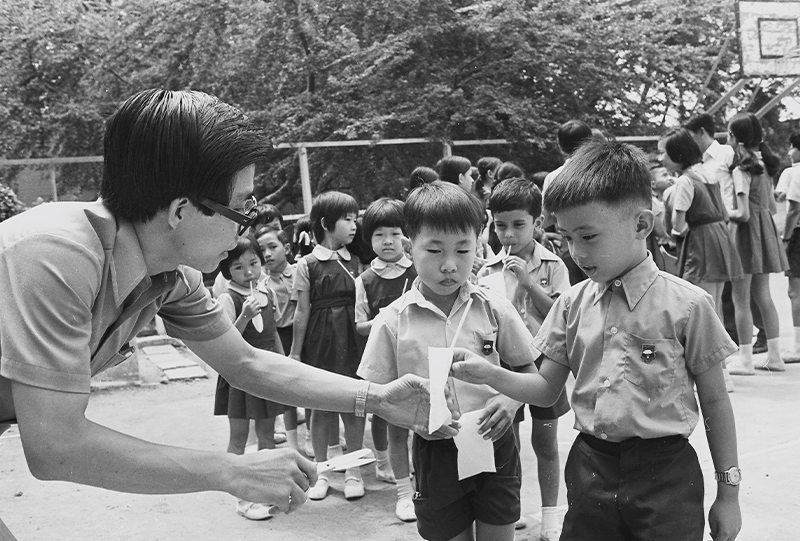

In schools across Singapore during the 1970s and 1980s, scenes of school children chugging milk in class daily were a common sight. Singapore students did not suddenly develop a taste for the drink though. Instead, this came about thanks to the School Milk Scheme, a government initiative that began in 1974.

Why Drink Milk?

In a letter to the Straits Times in 1982, the Ministry of Education explained that the main objective of the scheme was “to improve and upgrade the nutritional intake of primary school children by the consumption, regularly in school, of a substantial food item”. Milk, the ministry noted, was rich in proteins, carbohydrates and calcium which were “essential for healthy physical growth in our school children”.1

Former educator and historian Eugene Wijeysingha noted that Singapore was a poor country at the time. “Don’t forget. This was the seventies. That was the time I think when people in the country hadn’t become sufficiently affluent enough. There were still poverty gaps in different parts of the island,” he said in an oral history interview in 1995.2

The milk scheme idea came from Minister for Education Lee Chiaw Meng (1972–75) who “felt that nutrition was a crucial element in the learning process of a child”, said Wijeysingha. He surmised that Lee was most likely inspired by his visit to the United Kingdom where “every child must drink half a litre or so many pints of milk every day”, which was “part of the whole national health scheme”.3

In June 1973, the Education Ministry started selling powdered milk “at 10 cents a glass in 10 primary schools” located in housing estates, in preparation for rolling out the School Milk Scheme nationwide. “The scheme, open to all school children from Primary one to six, is a move to get the children accustomed to milk drinking as well as to provide a nourishing supplement to their diet,” said the ministry.4

The milk was supplied at 10 cents a glass from Monday to Friday, but it was free for underprivileged children. According to the ministry, “[r]esponse from parents and children have [sic] been very encouraging”, with many children looking forward to drinking the milk each day. “Parents too are very happy that their children are receiving this nourishing supplement at a minimum cost,” the ministry noted.5

As Fresh as Milk

The scheme proper was launched in February 1974 at 33 primary schools and later expanded to more schools. By the end of 1975, “children in 150 schools were drinking the milk”, with plans lined up to extend the scheme to another 140 primary schools by the end of 1976. Under the scheme, reconstituted pasteurised milk was sold at 10 cents a packet to students (this was increased to 12 cents from 1975), but children of parents receiving social welfare need not pay. The milk came in 150ml plastic packets and provided schoolchildren with a “wholesome, nutritious and low-cost snack” each day and aimed to “inculcate in them nutrition consciousness and good food habits”, said the ministry.6

At the start of the scheme, the milk was prepared by Ben Sunshine Dairies. Later on, the milk was supplied by Malaysian Dairy Industries, Singapore Cold Storage or Premier Milk. It was “delivered daily to the schools twice a day in time for recess”. Children could choose from five different flavours: vanilla, strawberry, pineapple, chocolate or for the not too choosy, plain milk.7

Although the scheme had initial teething problems such as “late and short deliveries”, these were eventually resolved and it became popular with both teachers and students. “Response is overwhelming. The pupils enjoy the delicious milk and some of them even buy extra packets for their brothers and sisters at home,” a teacher at River Valley English School told the Straits Times. Seah Peng Peng, a Primary 6 pupil, said: “I like the milk very much. I think if I drink a pack every day, I will have enough vitamins, proteins and brains to help me pass my examinations.” The ministry also approved two secondary schools to participate in the scheme.8

School tuckshop vendors were also said to be supportive of the scheme even though business at the drinks stall dropped. They “appreciated the importance of the scheme and have given the schools their full co-operation,” the Straits Times reported.9

Milk Scheme Goes Off

Over time however, interest in the scheme began to wane. In 1974, when the scheme was started, 63 percent of all primary school children drank milk daily but by 1980, this had fallen to 21 percent. The Education Ministry gave various reasons for the drop, such as children getting “fed up with drinking milk every day” and the “aggressive sales promotion” of soft drink companies having changed children’s preferences.10

When interviewed by the Straits Times in 1981, some children, like Primary Three pupil Li Yi Liang of River Valley Government Primary School, simply said “I don’t like milk” to explain why they did not participate in the scheme. He was on the scheme in Primary One but stopped after a year. “I don’t like to drink it. I thought you must take it, so I did,” he added. Later on, he switched to bringing his own flask of water from home. Betty Wong, 12, of the same school was more forthright. “Every time I drank it I felt like vomiting, so I stopped,” she said.11

The Education Ministry adopted various measures to reverse the drop in milk consumption. In August 1981, it “urged principals to encourage pupils to sign up for the scheme by telling them and their parents the nutritional value of milk”. It also changed the type of milk given to schools. Previously, schools were supplied with pasteurised milk twice a day at 20 cents a pack. However, the ministry announced in January 1982 that it would supply “packet milk which has been ultra heat treated to last longer”. Also known as UHT milk, it would contain 66 percent more milk and be supplied to schools in bigger packs at 20 cents each.12

Even with these measures, the milk distribution experience in some schools did not sit well with parents who complained that “pupils are forced to buy milk they don’t want”. Tan Tze Eng, an accountant, told the Straits Times in 1984 that at her daughter’s school, pupils would receive a month’s supply all at once. “The poor children have to lug 20 packets of milk home on the day the milk comes,” she said. “And those who forget their plastic bags are scolded by their teacher and have to get their friends to help them carry the milk home.”13

Teachers were also unhappy since distributing the milk and collecting the money ate into teaching time. Wijeysingha acknowledged that it was more work for teachers. “They had to collect money, they had to distribute the milk, they had to keep records. I am sure there was not an entirely happy reception from teachers,” he said in his oral history interview.14

One teacher noted that the milk scheme was not popular because students were “not allowed to choose the flavours they liked”, and the choice of flavours delivered “was left entirely to the supplier”. The same teacher found it “too troublesome” to allow the children to pick and choose the flavours they liked because time would be spent checking that the correct orders were delivered.15

Another teacher who could not get 20 pupils in her class to buy the milk resorted to buying the milk herself. “I know that some of my pupils hate the milk and I feel bad to force them to buy it, so I take the remainder home for my husband and sons,” she said.16

Milk for Children Advisory Council Set Up

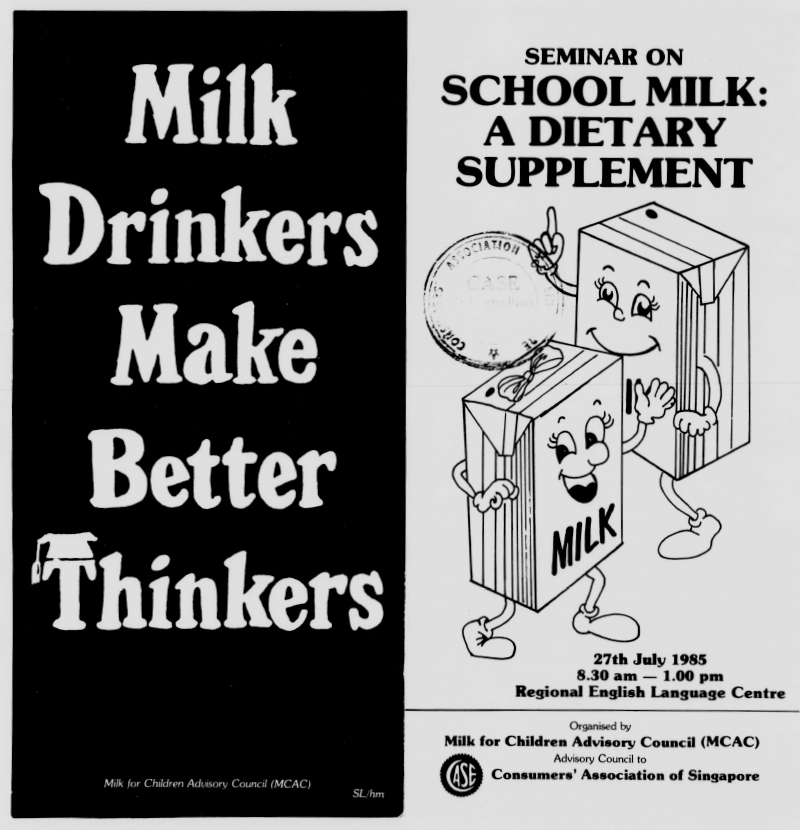

Possibly to further combat falling milk consumption in schools, the Consumers’ Association of Singapore set up the Milk for Children Advisory Council (MCAC) in 1982.17 The council complemented the Education Ministry’s efforts to encourage milk drinking in primary schools, said Ivan Baptist, the executive secretary of the Consumers’ Association.

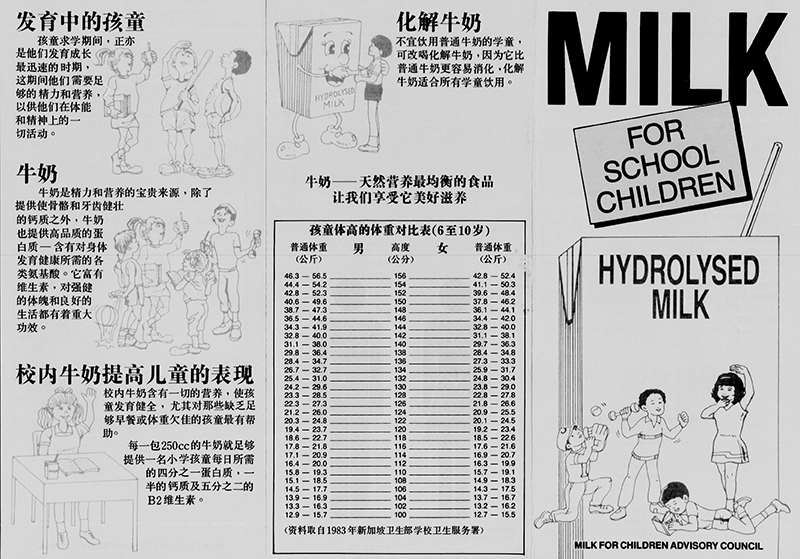

Chaired by Nalla Tan, the council aimed to promote milk as a dietary supplement for children aged nine months and upwards, secure sponsors to supply free or subsidised milk to children too poor to afford it as part of a diet, and promote milk as a fun and nutritious drink. The council also aimed to publish literature on the promotion of milk for children, as well as give advice to parents, teachers and consumers.18

“The council wants to create a general acceptance of milk as a nutritional drink,” said Baptist. “More importantly, we want children to enjoy the drink and not force it down their throats.” To make milk more attractive to children, the council planned to ask milk manufacturers to “package their product more attractively”.19 It also got children involved in the design of milk packages.

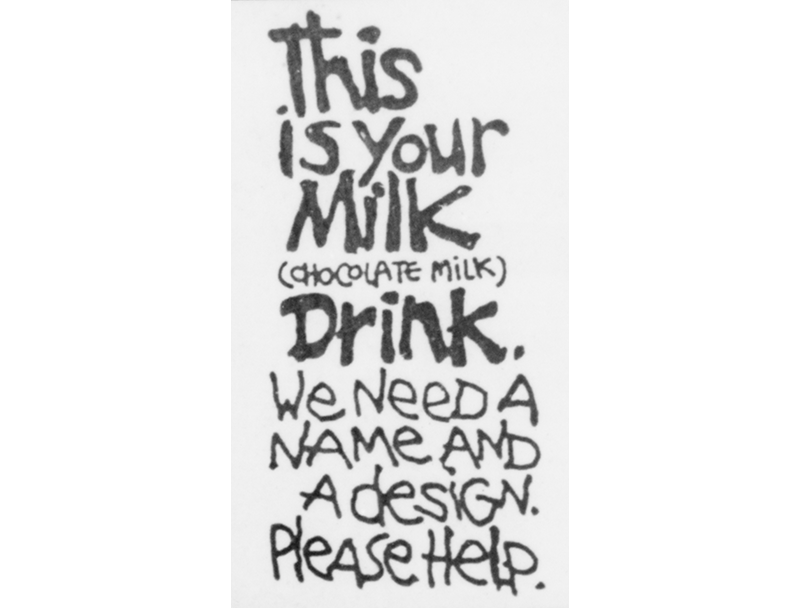

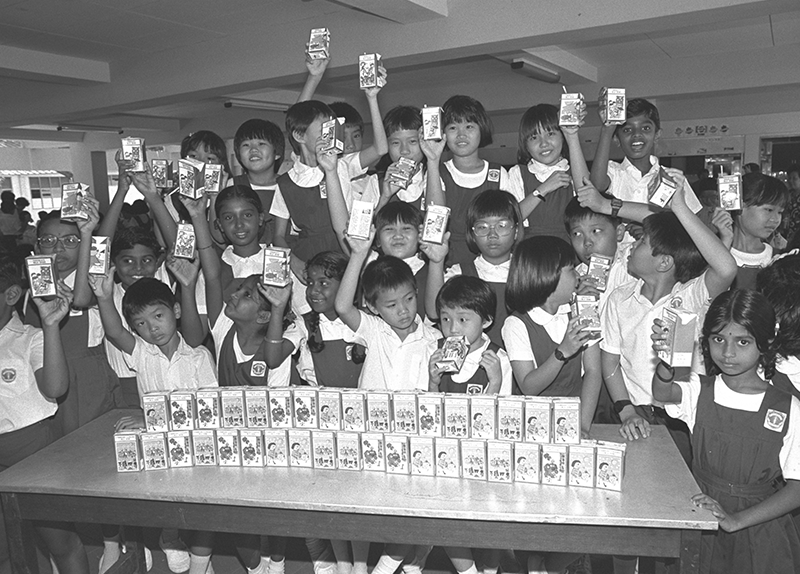

In January 1983, the “Name and Milk Package Design Contests” were held. To promote the contests, existing milk packs were replaced with new packaging bearing the message, “This is your milk” in a child’s handwriting, with the added text “We need a name and design. Please help”. A $10,000 cash prize was promised to the school that provided the winning entry. The “name and age of the winner and his or her school’s name” would also be printed on the new packs.20

Children were rewarded for drinking milk. Between June and November 1983, children who accumulated 30 milk pack flaps received a “magic” ruler and an eraser-pencil cap. The council ordered 200,000 rulers and eraser-pencil caps costing a total of $20,000 to run the promotion, which ended on 4 November that year.21

To make the milk more palatable, the council looked into introducing new flavours beyond the five initially offered. A Straits Times article on 10 November 1984 noted that the council “planned to introduce local fruit flavours but found [that] the flavours were not available in sufficient quantities”. Furthermore, some flavours like blackcurrant and peach were not well received when tested on children.22

In November 1984, the council even came up with an event, appropriately named Milk Day. The inaugural event was held at the Mandai Zoological Gardens and attended by thousands of primary and pre-primary students. “The idea is to get children to participate in the activities and to make milk-drinking fun for them,” said Nalla Tan, the council chairman. Each child received two packets of a new apricot-flavoured milk, which they drank with other food like sandwiches and cakes. The children were also entertained by an animal show, ventriloquist performances and a colouring competition.23

Milk Day in 1985 was held at the zoo over two days. The 5,500 children who visited the zoo on 19 November did not let the rain dampen their excitement. On Milk Day 1987 at Jurong Bird Park, each child received two packets of the newly launched sweet corn flavour.24

Children Sour on Milk Scheme

The council’s initial efforts were successful. By February 1983, “about 27,000 of the 300,000 schoolchildren in Singapore were drinking milk compared to 24,300 a year ago”. In 1983, “primary and pre-primary schools and the People’s Association kindergartens bought about 10 million packs under the milk scheme”. In 1984, “pre-schoolers and primary schoolchildren drank the same amount within 10 months”, which meant that on average, a million packets of milk were drunk per month.25

While further numbers regarding milk consumption are not available, developments suggest that the programme was running into headwinds caused by Singapore’s growing prosperity. Although the initial impetus of the milk scheme was to improve children’s nutrition, by the late 1980s, the concern became less of nutrition and more about childhood obesity. In fact, in 1988, the School Milk Scheme was temporarily stopped because health experts feared it could be a cause of obesity, according to Baptist.26

In August that year, the seminar “Milk for Better Living” was held and some 350 principals, teachers, nutritionists, doctors and Health Ministry officers convened at the Pan Pacific Hotel to discuss who should be included in the School Milk Scheme. The seminar also reviewed the MCAC’s role in light of “the prevailing food habits, the nutritional status, and the health of schoolchildren”.27

At the seminar, council chairman Chua Sin Bin noted that “there is no direct link between obesity and the drinking of milk in schools”, contrary to the earlier concerns of health experts. He said that since January 1988, full-cream milk had been replaced with low-fat milk even though full-cream milk did not lead to obesity in children. The reason, he said, was “psychological”, and the replacement was to “stress the need to reduce the consumption of fats”.28

Uma Rajan, the medical director of the School Health Services, noted that there were “changes in the dietary profiles of Primary One pupils” due to “increased spending power and the greater freedom children had in the choice and quantity of food.” Hence, “the child of the ’80s is taller and heavier than the child of the ’60s”.29 The observation by Rajan suggested that childhood malnutrition was much less of a problem in the 1980s than it had been in previous decades. Indeed, it seemed that by the late 1980s, obesity among children, rather than malnutrition, was a bigger concern. The milk scheme, it would appear, had outlived its usefulness. In Wijeysingha’s analysis, “gradually, as people became more affluent, there was no need to sustain this scheme” and it “died a natural death”.30

Notes

-

Chew King Hwan, “Ministry on Course That Was Scrapped and Aim of School Milk Scheme,” Straits Times, 8 February 1982, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Eugene Wijeysingha, oral history interview by Jesley Chua, 28 June 1995, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 33 of 54, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001595), 406–07. ↩

-

Eugene Wijeysingha, oral history interview, 28 June 1995, Reel/Disc 33 of 54, 406–07. ↩

-

“Ministry Starts Sale of Milk,” New Nation, 15 June 1973, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Edmund Teo, “Milk Scheme a Big Hit So Plan Will Cover 188 More Schools,” Straits Times, 21 September 1975, 8; Edmund Teo, “100,000 Take Part in Milk Scheme for Students,” Straits Times, 21 March 1976, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mohd Yusoof, “Drink a Pint a Big Hit in Schools,” Straits Times, 19 April 1974, 6; May Ho, “‘Alarming’ Drop in Pupils Taking Part in Milk Scheme,” Straits Times, 26 August 1981, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mohd Yusoof, “Drink a Pint a Big Hit in Schools”; Teo, “100,000 Take Part in Milk Scheme for Students.” ↩

-

Mohd Yusoof, “Drink a Pint a Big Hit in Schools.” ↩

-

Ho, “‘Alarming’ Drop in Pupils Taking Part in Milk Scheme.” ↩

-

Ho, “‘Alarming’ Drop in Pupils Taking Part in Milk Scheme.” ↩

-

May Ho, “Ministry Hopes to Boost Milk Sale to Pupils,” Straits Times, 9 January 1982, 14; “Schools to Get New Type of Milk,” Straits Times, 16 January 1982, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hedwig Alfred, “Milk Plan Goes Sour in Some Schools,” Straits Times, 2 May 1984, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Why It Isn’t Popular With Kids,” Singapore Monitor, 8 January 1983, 4. (From NewspaperSG); Eugene Wijeysingha, oral history interview, 28 June 1995, Reel/Disc 33 of 54, 406–07. ↩

-

Alfred, “Milk Plan Goes Sour in Some Schools.” ↩

-

Tay Eng Soon, “Inauguration of the Milk for Children Advisory Council Singapore,” speech, Shangri-La Hotel, 8 December 1982. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. tes19821208s); June Tan, “One in Three Goes to School Hungry…,” Straits Times, 9 December 1982, 40. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Children to Get Taste of Goodness of Milk,” Straits Times, 9 December 1982, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Plan to Boost Milk’s Image Among Kids,” Straits Times, 30 October 1982, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ho Kah Leong, “Prize Presentation and Exhibition of the Milk for Children Advisory Council (MCAC) Name and Milk Package Design Contests,” speech, Toa Payoh Branch Library, 19 July 1983. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. hkl19830719s); “Milk Carton for School Children Packs a Message,” Straits Times, 28 December 1982, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Gifts to Get Children to Drink More Milk,” Straits Times, 29 June 1983, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“1,000,000,” Straits Times, 10 November 1984, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Nov 13 Is Milk Day,” Straits Times, 10 November 1984, 15; “Milk Day in September,” Straits Times, 15 June 1984, 10; Chee Li Choo, “Big Turnout at Zoo Day of Festivities As Primary Students Celebrate Milk Day,” Singapore Monitor, 13 November 1984, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Matilda Gabriel, “Children’s Spirits Get a Jumbo Lift,” Straits Times, 20 November 1985, 16; “Bid to Get Pupils to Continue Milk Habit,” Straits Times, 10 July 1987, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Milky Message Scores Its Goal…,” Straits Times, 10 March 1983, 9. (From NewspaperSG); “1,000,000.” ↩

-

Serene Lim, “Milk Scheme Is Stopped Temporarily,” Straits Times, 12 August 1988, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim, “Milk Scheme Is Stopped Temporarily.” ↩

-

Lim, “Milk Scheme Is Stopped Temporarily”; “Needy Pupils Still Getting Free Milk,” Straits Times, 14 August 1988, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Eugene Wijeysingha, oral history interview, 28 June 1995, Reel/Disc 33 of 54, 406–07. ↩