Growing Food in a Garden City

Urban edible gardening in Singapore might be all the rage now, but the movement has roots that date back to the early 20th century.

By Fiona Williamson and Joshua Goh

In June 2020, the National Parks Board (NParks) launched Gardening with Edibles, an initiative that saw the distribution of nearly 460,000 seed packs to interested households. Each pack contained approximately 1,000 vegetable seeds, allowing Singaporeans to grow a few rounds of crops ranging from tomatoes to leafy vegetables like kailan.1 The initiative’s main purpose was to drive home the importance of food security as part of a wider national campaign, Our Singapore Food Story.2

Due to Singapore’s heavy reliance on imported food, most locals rarely have a hand in producing the food they eat. In 2020, fewer than 3,100 Singapore residents (or 0.14 percent of the labour force) were involved in industries such as agriculture and fishing.3 Gardening with Edibles bridges this wide disconnect between farm and table by providing Singaporeans with the experience of growing their own food.

Edible gardening is not a recent phenomenon in Singapore; Gardening with Edibles was preceded by the Grow More Food campaigns. These initiatives and practices of edible gardening in modern Singapore emerged from a confluence of food security concerns and planning ideals from the Garden City Movement in Britain, and demonstrate just how deeply rooted edible gardening is in the Singapore Story.

Edible Gardens for Health and Wellbeing

With the advent of a Garden City Movement in the late 1800s, the connection between gardens and urban wellbeing was widely touted by social improvers and town planners in Britain and the U.S. In Britain, for example, Edwin Chadwick and Benjamin Ward Richardson had both proposed models for healthy cities wherein gardens played significant roles in urban wellbeing.

Richardson’s model city narrative Hygeia (1876) argued that cities must have tree-lined boulevards and green spaces, and homes should be “surrounded with garden space, [to] add not only to the beauty but to the healthiness of the city”.4 One of the most influential writers of the late 19th century was Ebenezer Howard, whose Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1898, reprinted 1902) birthed the concept of the garden city “to raise the standard of health and comfort of all true workers of whatever grade – the means by which these objects are to be achieved being a healthy, natural, and economic combination of town and country life”.5

Such ideas eventually found their way into official circles in Singapore through trans-imperial knowledge networks. In the 1910s and 1920s, a series of imperial health conferences drew connections between planning, housing and health, and linked ideas of social justice amid the popularity of new labour movements to the accessibility of green, healthy space and food. These concerns intensified at the outbreak of war in 1914, when many people failed to pass the basic health requirements to enter military service, probably the first time such a mass health screening had taken place.6

While these urban planning movements did not directly address edible gardens, some of Singapore’s health institutions did set up kitchen gardens to improve patient wellbeing. In 1917, for example, an institution for the mentally ill had created a kitchen garden. By 1918, “excellent fresh vegetables were available … aggregating 10,534 pounds for the staff and ‘inmates’ grown by the patients themselves”, reported the Singapore Free Press.7 Edible gardens had been incorporated into Singapore’s hospitals long before Khoo Teck Puat Hospital developed its “A garden in a hospital” concept.8

Edible Gardens for Food Security

At the same time, food security concerns provided further impetus for colonial authorities to promote edible gardening as a means of ensuring the wellbeing of working-class families. This was not a new idea as there had been edible gardens in British cities since the late 1700s. Local governments rented out small plots of land to urban dwellers who wanted, or needed, to grow their own food, rather than buy it.9 Such allotments proved to be an enduring aspect of working-class British culture all the way through the 20th century.10

From the 1910s, there had been growing international concern that agricultural output would not match population growth. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 demonstrated that when global supply lines were severely disrupted for long periods, countries overly reliant on imported goods struggled to be self-sustainable. The Singapore Free Press remarked in 1918 how “[t]he cost of a few sprigs of ‘chukup manis’, a few scraggy beans, or a cucumber or two, is astonishing in Singapore … and altogether the supply of locally grown foods is altogether inadequate”.11

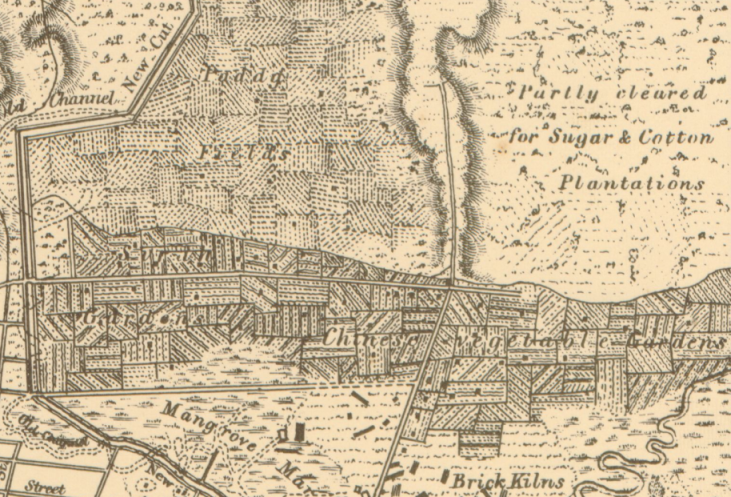

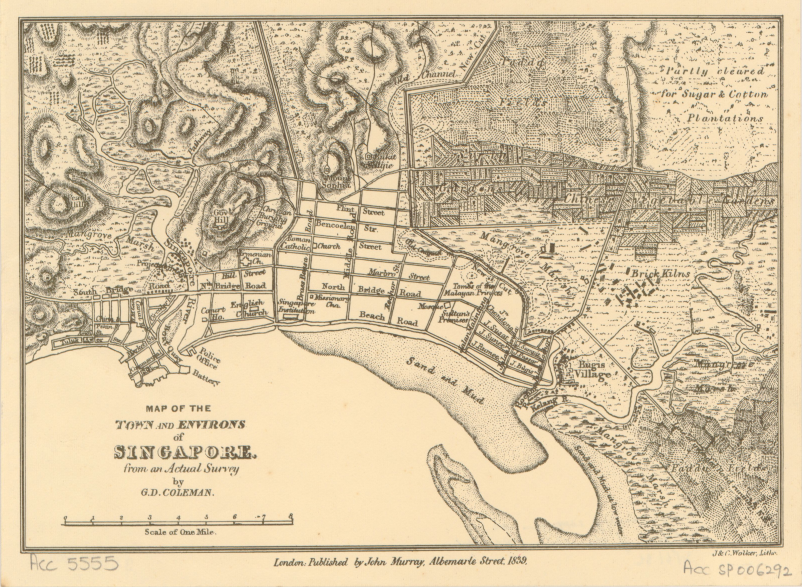

The local situation had been compounded by the gradual erosion of market gardening in Singapore, traditionally undertaken in the 19th century by many Chinese communities to the east of the town centre, around Rochor through Bendemeer.12 By 1919, an impending rice shortage across Malaya meant that plantation workers were encouraged to “get busy and cultivate gardens, planting food stuffs such as ragi [finger millet], yams and maize to be eaten instead of rice”.13

The 1920s and 1930s saw a string of environmental crises, which either directly or indirectly affected Singapore and other parts of Asia. Soil erosion due to unsustainable farming practices and unusually severe periods of drought led to major agricultural producers such as India, the U.S. and China suffering severe economic hardship, with a knock-on effect on global food supply and prices. In Singapore, the concurrent decline in the rubber industry in the early 1920s meant less disposable income for many families. This triggered a mass interest in growing their own food.

Across Malaya, the British government started various campaigns to teach schoolchildren gardening skills and provided incentives for better-off people to convert their flower gardens into vegetable patches. In 1932, for example, “It was decided, especially in view of the economic situation, that … an effort should be made to stimulate interest in home gardens by village competitions open to all races.”14

Even government institutions had functional gardens. Government House, for example, had a garden where “nearly 20 varieties of vegetables” were grown over 130 acres, including “lettuce, cucumber, mint, radishes, and water cress”, which were collected daily for their own kitchens. “Rarely does Government House have to go to the markets for its vegetables and there is often such an abundance that quantities over domestic requirements are sent to the Child Welfare Centre”.15 Composting for sustainability and productivity was also strongly encouraged to “[make] the people of Malaya self-supporting in vegetable food.”16

The pressure to grow more food increased in 1939 with the start of the Second World War. By now, there was a concerted Grow More Food campaign coordinated through various government departments, including the Rural Board and the Department of Agriculture, alongside the Malayan Agricultural and Horticultural Society (MAHA), with communications managed by the Department of Information.17 Aside from information disseminated through posters and schools, “demonstration plots” were set up in places like Pasir Panjang Park, “to stimulate public interest in vegetable gardening … particularly green leafy vegetables and fruits”.18

Mehervan Singh, a Singapore resident who had moved to the island from India as a child, recalled the government employing “student gardeners” who were to learn how to grow vegetables and in turn teach the general public. Singh was one such gardener and had been trained by the then director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Dr R. E. Holden, at the outbreak of the war in 1939. He was also “attached to one Mr Yap, an agricultural inspector” where he “learned a great deal about growing vegetables” often through visiting market gardens. Singh put this “knowledge to good use at a vegetable garden set up along Ayer Rajah Road and another off Pasir Panjang Road” where they grew produce including kangkong (water spinach), long beans, French beans, cucumbers, bitter gourds, green pumpkins, lady’s fingers, brinjals, chillies, tomatoes, radishes, and papayas.19

That same year, an experiment in self-sustainability was undertaken at the Health Department with composting supplies drawn “from about 10,000 inhabitants” and around 14 acres of land “cultivated for the production of vegetable and fruit”. The produce was “shared among the Health Department labourers … it is believed that over 200 of them [saved] at the rate of 20 cents a week as a result of their daily ration of vegetables”.20

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), continued food shortages and exorbitant prices saw the continuation of the Grow More Food campaign under the new government. At Farrer Park, for example, there had been “a nice patch of grassland situated just opposite Race Course lane” which was a children’s playground. When the war broke out, “the British Military Authorities … dug trenches and man-holes all over … When the [Japanese] came in, they encouraged the planting of food. So, people turned the playground into a miniature farm. The planks from the swings and see-saws went to help in the building of squatters’ huts.”21

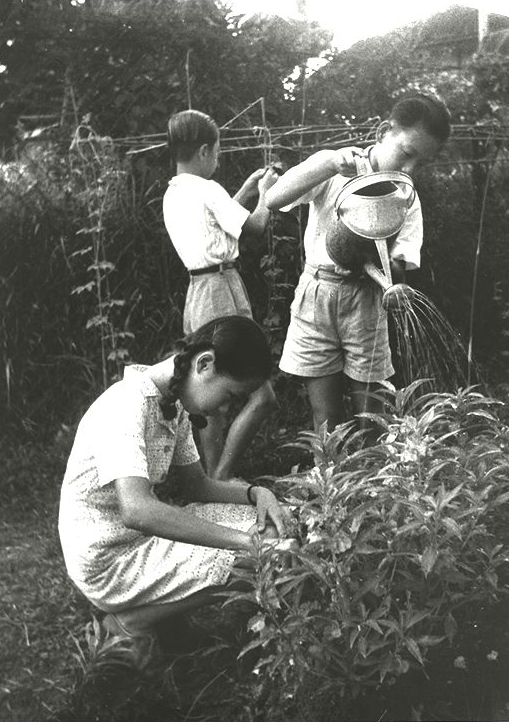

Gardening was added to the school curriculum, “both for the good of the soul” and to address food shortages.22 Born in Singapore in 1930, educator Bernard Fong recalled “[o]ne interesting aspect of school life then was vegetable gardening. The whole field of St. Joseph was all planted with home grown vegetables … We were all city boys and did not do any planting or home gardening … We were planting all sorts of vegetables… We had to make our own compost heap. Almost every morning we spent some time doing that kind of gardening… [the harvest was] given to the pupils.”23

Japanese propaganda encouraged self-sufficiency and exhibitions illustrated how substitute foodstuffs could be manufactured to deal with the dearth of normal foods.24 Ismail bin Zain, born in 1912 and who lived through the Japanese Occupation, tells of his experience with the Japanese Grow More Food campaign: “From the beginning, they encouraged people to plant food. So every space when it can be grown… people will start growing food. Orchard Road is a very long road… at that time we had grass verge, about a few feet… All these places were being planted with tapioca.”25 The Japanese also created two “model” agricultural colonies as experimental, supposedly self-sustainable villages – Endau and Bahau – in Malaya where Malays, Eurasians, and Chinese were conscripted to live and work.26

The authorities continued to promote edible gardening in urban Singapore even after the war. Due to the widespread destruction caused by the war, many of the island’s traditional food suppliers, such as Burma and Thailand, did not reach pre-war levels of agricultural production until 1947.27 This resulted in food shortages and skyrocketing inflation during the initial years of the post-war period. Thus, a February 1946 Malaya Tribune editorial urged a hasty return to edible gardening: “Everywhere we see the ruins of gardens torn up with gay abandon during the delirious days immediately following the reoccupation. These gardens should be replanted at once with green vegetables and even the despised tapioca”.28

Unsurprisingly, the British Military Administration (BMA) quickly revived the pre-war Grow More Food campaign just three months after resuming control of Malaya in September 1945.29 Seeking to encourage locals to “grow more food on all available garden spaces”, the BMA endeavoured to provide copious support in the form of subsidised land and seeds to anyone wanting to set up small-scale vegetable gardens to feed themselves and their families. Garden plots could be rented for as little as 20 cents a month.30

The authorities attempted to generate interest and enthusiasm for edible gardening by organising Grow More Food exhibitions, which provided gardeners with opportunities to competitively exhibit their produce.31 Though food security concerns remained on the policy agenda even after Singapore achieved self-government in 1959, the Grow More Food campaign’s initial focus on citywide edible gardening gradually gave way to an emphasis on ramping up commercial food production.32

The importance of the edible gardens promoted by the BMA during the post-war period cannot be overstated. Born in 1944, Raymond Ho, who had spent his childhood in Bedok, remembers that such gardens were an indispensable source of food for his impoverished family of eight crammed into a “small little attap house with one bedroom” at Bedok Corner.33 Apart from seaweed foraged from the beach, his family also cultivated a “little garden” where they “planted a little bit of kangkong, a little bit of bayam [Chinese spinach], a little bit of potatoes and whatever”. They also kept several pigeons in the garden as a source of protein. As Ho put it, “It wasn’t bad, don’t have to go to market”.34

Even those with seemingly secure middle-class jobs maintained edible gardens to save money. For instance, Joginder Singh, who had moved to Singapore in the 1920s when his father had been transferred here, remembers cultivating a piece of land owned by his father after the war: “[M]y father had a plot of land of his own. And immediately after office, and before going to office every morning, I would be there in that plot of land, trying to make vegetables grow… And whenever we eat the vegetables, they had to come out of our own garden… We did have to buy, no doubt, but then what we planted also was quite a substantial amount.”35

Edible Gardens for Community Cohesion

Though the edible gardens planted under the Grow More Food campaigns are long gone, edible urban gardening continues to be practised in space-scarce Singapore, especially in community gardens. Run by grassroots organisations like Residents’ Committees, community gardens are green spaces that can be found in many private and public housing estates across the island.

Most of the gardens we see today constitute part of NParks’ Community in Bloom (CIB) initiative. First launched in May 2005 at Mayfair Park Estate, CIB aims to “encourage people to come together to form gardening groups within their communities”.36 As of today, there are over 1,900 community gardens established under CIB.37 Though not envisioned as food production spaces, edible plants like kangkong are often grown in community gardens. In fact, 80 percent of the community gardens in Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates grow some sort of edible plant.38

According to former NParks director Ng Cheow Kheng, who oversaw the creation of the CIB initiative, the term “Community in Bloom” was directly adapted from the Canadian “Communities in Bloom” movement,39 which involves various municipalities across Canada competing to create aesthetically pleasing urban green spaces.40

Canada’s Communities in Bloom was in turn modelled on – and even obtained expert guidance from – the Britain in Bloom initiative,41 which is similarly a nation-wide competition that sees Britain’s various towns, cities, and villages compete in beautifying their built environments by means of gardens.42 Hence, despite its relatively recent origins, Singapore’s CIB can nonetheless trace its genealogy all the way back to the Garden City Movement in Britain.

Conclusion

In his history of community gardening in America, Thomas Bassett argues that these green spaces were often direct responses to crises such as war, economic upheaval and accompanying social change. For example, the so-called Relief Gardens programme (1930–39) was a means to ensure the food security of American workers made destitute by the Great Depression. Similarly, the Victory Gardens movement (1941–45) was a response to stresses placed upon America’s agricultural food production systems by the Second World War.43

From this perspective, NParks’ Gardening with Edibles initiative can be regarded as the latest example of how edible urban gardening has been used by governments to respond to food security concerns. The British and the Japanese authorities who governed Singapore during the 20th century launched a series of Grow More Food campaigns to address agricultural supply disruptions because of war and environmental crises. In the same way, NParks’ Gardening with Edibles can be regarded as part of the Singapore government’s policy response to an increasingly volatile global food security landscape.44

Indeed, the history of urban gardening holds up a mirror to contemporary concerns. In Asia’s developed cities, urban wellbeing and food security continue to be issues. The trend of greening cities, for example, is motivated largely by the same reasons that the model city was designed: to create a healthy space to live in. Short- to medium-term disasters, such as the Ukraine War or the COVID-19 pandemic, and long-term situations like the climate emergency have, and will, disrupt global and local trade supplies, highlighting the need for local alternatives, reducing carbon footprint and supporting the local economy.

It is ironic, however, that to earlier generations, the farm-to-table concept, or growing food in a back garden, balcony or community allotment would not have been considered trendy or green, but simply essential to everyday life. Urban gardening may be one of today’s big trends, but it is by no means new and is part of multiple narratives that have influenced formal and informal gardening practices over the years. The study of all these connected themes throughout history provides a connection to our past and a way to better prepare for our future.

Fiona Williamson is an Associate Professor in Environmental History and Joshua Goh is a PhD candidate on the Asian Urbanisms Postgraduate programme at Singapore Management University.

Fiona Williamson is an Associate Professor in Environmental History and Joshua Goh is a PhD candidate on the Asian Urbanisms Postgraduate programme at Singapore Management University.

Notes

-

Goh Chiow Tong, “NParks to Give Packets of Vegetable Seeds to Households to Encourage Home Gardening” Channel News Asia, 18 June 2020, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/nparks-give-packets-vegetable-seeds-households-encourage-home-gardening. ↩

-

“Our SG Food Story”, Singapore Food Agency, 21 August 2020, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/fromSGtoSG/our-sg-food-story. ↩

-

As of June 2020, only 3,100 residents were employed in industries classified as “Others”, which includes agriculture, fishing, quarrying, utilities, and sewerage and waste management. This represents only 0.14 percent of the total labour force (as of June 2019). See Manpower Research and Statistics Department, Singapore Yearbook of Manpower Statistics 2020 (Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, 2020), A7, https://stats.mom.gov.sg/iMAS_PdfLibrary/mrsd_2020YearBook.pdf. On the contribution of local farms to Singapore food’s supply, see “Our Singapore Food Story- The Three Food Baskets”, Singapore Food Agency, 13 August 2021, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-farming/sgfoodstory. ↩

-

Benjamin Ward Richardson, Hygeia: A City of Health, (London: Macmillan and Co, 1876), 20. ↩

-

Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrow, (London: S. Sonnenschein & Co., 1902), 22. ↩

-

Robert Freestone and Andrew Wheeler, “Integrating Health into Town Planning: A History,” in The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future, ed. Hugh Barton, Susan Thompson, Sarah Burgess, Marcus Grant (Oxon and Routledge, 2015), 17–36. ↩

-

“Vegetable Growing In Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 February 1919, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Salma Khalik, “Khoo Teck Puat Hospital Wins International Design Award, Beating US and Japanese Buildings” Straits Times, 13 December 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/ktph-wins-international-design-award-beating-us-and-japanese-buildings. ↩

-

N. Flavell, “Urban Allotment Gardens in the Eighteenth Century: The Case of Sheffield,” The Agricultural History Review 51, no. 1 (2003): 95–106. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

See Margaret Wiles, The Gardens of the British Working Class (London: Yale University Press, 2014) ↩

-

“Malaya’s Food Supply,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 January 1918, 50. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

These gardens are clearly marked on National Archives (Singapore), Map of the Town and Environs of Singapore from an Actual Survey by G.D. Coleman, 1839, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP006292) ↩

-

“Shortage of Rice,” Malaya Tribune, 23 April 1919, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Home Gardens in Malaya,” Malaya Tribune, 21 November 1931, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Fine Vegetables From Governor’s Gardens,” Straits Times, 8 October 1940, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Good Use Now Being Made of Singapore’s Refuse,” Malaya Tribune, 15 November 1940, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“This Means You,” Morning Tribune, 10 August 1940, 2; “‘Grow More Food’ Campaign,” Straits Times, 3 November 1940, 5. (From Newspaper SG) ↩

-

“Vegetable Growing To be Increased,” Malaya Tribune, 12 October 1939, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mehervan Singh, oral history interview by Pitt Kuan Wah. 17 May 1985, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 16 of 67, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000553) ↩

-

Tse-Kwang Hsu, “Children’s Paradise in Farrer Park” The Rafflesian 21, no. 2 (November 1947): 18–20. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 373.5957 R) ↩

-

Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack, War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press), 207. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.53595 BLA) ↩

-

Bernard Fong Fook Chak, oral history interview by Verena Tay Siew Hin, 19 February 1993, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 8, 28, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001406), 28. ↩

-

Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2009), 307. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 FRO) ↩

-

Ismail bin Zain, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 5 September 1985, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000601), 46. ↩

-

Ismail bin Zain, interview, 5 September 1985, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, 44–47. ↩

-

Paul H. Kratoska, “The Post-1945 Food Shortage in British Malaya,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 19, no. 1 (March 1988): 32–33. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Spectre of Famine,” Malaya Tribune, 21 February 1946, 2–3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Grow More Food,” Straits Times, 14 December 1945, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Measures to Relax Moratorium Being Examined,” Sunday Tribune (Singapore), 25 November 1945, 4; “Government Aid to Grow More Food,” Indian Daily Mail, 9 March 1946, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“S’pore ‘Grow More Food’ Exhibition,” Malaya Tribune, 8 August 1946, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See “Found—Way to Grow More Food,” Straits Times, 28 May 1961, 5. (From Newspaper SG) ↩

-

Raymond Ho Chee John, interview by Joseph C. Pereira, 1 June 2007, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, National Archives of Singapore, (accession no. 003163), 1–2. ↩

-

Raymond Ho Chee John, interview, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, 12–13. ↩

-

Joginder Singh, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 7 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 11, National Archives of Singapore, (accession no. 000365), 93–94. ↩

-

National Library Board, Singapore and National Parks Board, Singapore, Community in Bloom: My Community, My Gardens (Singapore: National Library Board and National Parks Board, 2014), 11. (From BookSG) ↩

-

“Community Gardens,” National Parks Board, last updated 24 April 2023, https://www.nparks.gov.sg/gardening/community-gardens. ↩

-

“New National Masterplan to Encourage More to Garden,” National Parks Board, 2 November 2017, https://www.nparks.gov.sg/news/2017/11/new-national-masterplan-to-encourage-more-to-garden. ↩

-

Ng Cheow Kheng, oral history interview by Kiang-Koh Lai Lin, 17 June 2014, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 10, National Archives of Singapore, (accession no. 003879), 86. ↩

-

Marc Lalonde, “Vaughan, Canada, Undertakes Study to Assess the Benefits of Public Green Spaces,” in Global Models of Urban Planning: Best Practices Outside of the United States, ed. Roger L. Kemp and Carl J. Stephani (Jefferson:McFarland & Company, 2014), 195–97. ↩

-

Richard Benfield, Garden Tourism (Oxofordshire: CABI, 2013), 132. (From Naitonal Library, Singapore, call no. 338.4791 BEN); See also “About Us,” Communities in Bloom, 2023, https://www.communitiesinbloom.ca/program/about-us/. ↩

-

Benfield, Garden Tourism, 132–33. ↩

-

Thomas Bassett, “Reaping on the Margins: A Century of Community Gardening in America,” Landscape 25 (January 1981): 1–8, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279907300_Reaping_on_the_margins_A_century_of_community_gardening_in_America. ↩

-

Siau Ming En, “The Big Read: Far From People’s Minds, but Food Security a Looming Issue,” Today Online, 26 May 2017, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/big-read-far-peoples-minds-food-security-looming-issue. ↩