A Scientific Adventure: The Life and Legacy of Dr Lee Kum Tatt

Dr Lee Kum Tatt was instrumental in the development of Singapore’s scientific and industrial landscape.

By Sharad Pandian

On 6 September 1959, eight children died, and 31 others from across Singapore were hospitalised. No one knew what caused the tragedy, and the Singapore government’s Department of Chemistry (then under the Ministry of Health) was tasked to investigate.

Hearing that three of the deceased children had had homemade barley drinks before their deaths, the department speculated that barley might be the culprit, prompting the government to issue a statement warning the public to avoid the grain. Dr Lee Kum Tatt, the toxicologist on the case, recalled, “Ridiculous and far-fetched as this suggestion might be, we had to make some kind of statement to calm the public.”1

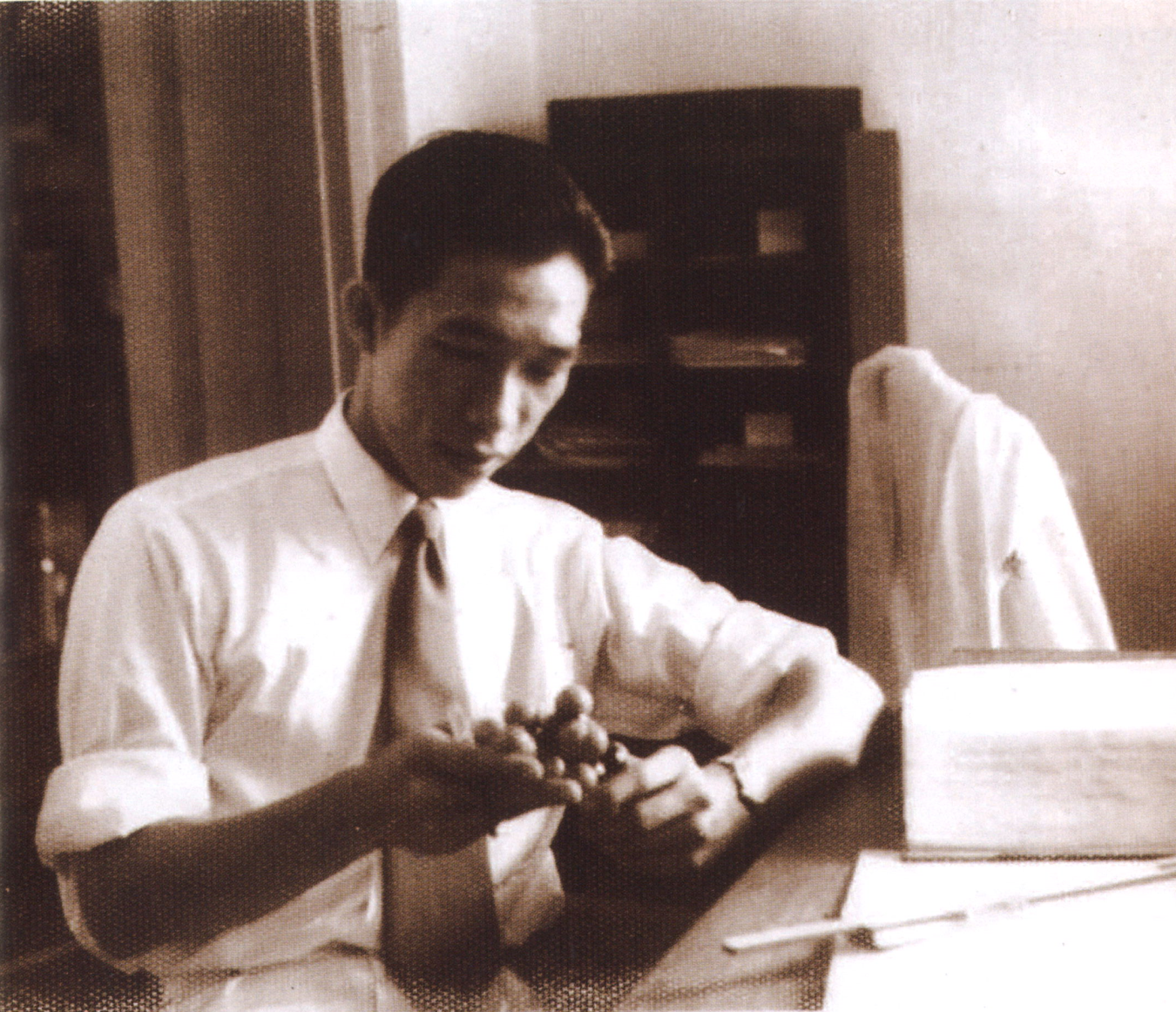

Dr Lee Kum Tatt at the research laboratory of the University of Malaya, 1953. Image reproduced from A Fabulous Journey (2012, Singapore: The Word Press). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 540.92 LEE)

Dr Lee Kum Tatt at the research laboratory of the University of Malaya, 1953. Image reproduced from A Fabulous Journey (2012, Singapore: The Word Press). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 540.92 LEE)It was a race against the clock to identify and isolate the source. Lee and his small team of two laboratory assistants and a chemist worked tirelessly to prevent further fatalities. Given that all the children had had barley drinks, Lee and his team collected 15 food samples from the victims’ homes, including barley. Mice were fed cheese injected with the samples, and the single mouse given the barley extract dropped dead. Further analysis showed the presence of Parathion, an insecticide banned in Singapore.2

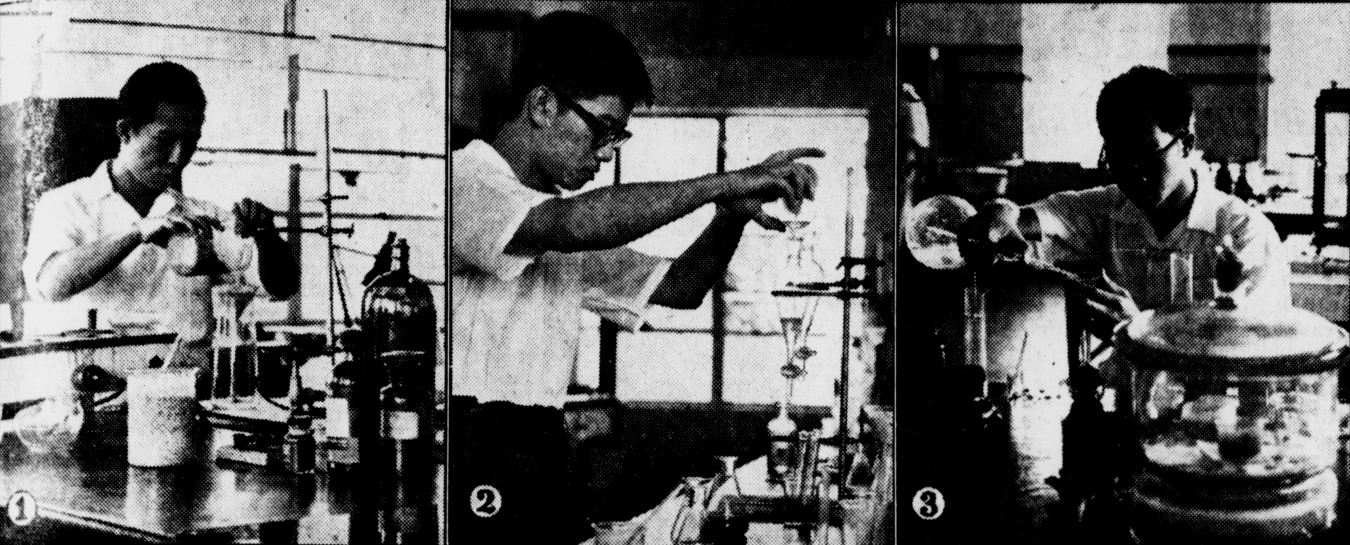

Dr Lee Kum Tatt (left) and his team, Theng Chye Yam (middle) and Ng Hon Wing (right), at work in the laboratory in search of the toxin that killed eight children in 1959. Image reproduced from “Barley Deaths: The Lab Boys Get to Work…,” Straits Budget, 16 September 1959, 13. (From NewspaperSG).

Dr Lee Kum Tatt (left) and his team, Theng Chye Yam (middle) and Ng Hon Wing (right), at work in the laboratory in search of the toxin that killed eight children in 1959. Image reproduced from “Barley Deaths: The Lab Boys Get to Work…,” Straits Budget, 16 September 1959, 13. (From NewspaperSG).The incident might have been the first time the public had heard of Lee, but over the years, he would go on to play a leading role in building scientific infrastructure in the country: this includes the Singapore government’s Department of Chemistry, the Science Council, Singapore Polytechnic, the Singapore Institute of Standards and Industrial Research (SISIR), and the Singapore Science Centre. These contributions are all the more impressive when set in their historical context – the dangerous, uncertain Malaya of the mid-20th century.

Early Years

While he described himself as “quite apolitical,”3 Lee was nonetheless swept up in the dramatic political currents of his time – from the Second World War and violent postwar nationalism, to the Malayan Emergency and Malayanisation of the civil service.

His frequent relocations testify to the comparatively porous world that existed then. Born in Medan, Indonesia, in 1927, Lee moved to Penang, Malaya, when he was six months old to live with his maternal grandparents. In 1940, he returned to his parents in Medan. Within a year, war broke out, and the island was occupied by the Japanese.

Lee described those years as “very traumatic”.4 He stopped school and undertook jobs like selling charcoal, black marketing and farming. And yet, at least retrospectively, he thought those years did him some good, ridding him of “ego and false pride” while teaching him to value honour and dignity instead.5

The end of the war saw clashes between Indonesian nationalists and the Dutch who were trying to reassert their colonial dominance. Lee was a volunteer with the International Red Cross as an interpreter for the British Army (sent to disarm the Japanese). When his family was targeted for associating with foreigners, Lee and his family were forced to flee to Penang. There, he was able to complete his schooling and gain admission into Raffles College in 1948 to study chemistry.6

Science students from the 1948 cohort at Raffles College, 1948. Raffles College Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Science students from the 1948 cohort at Raffles College, 1948. Raffles College Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Lee attained his Bachelor of Science three years later, in 1951. He graduated with honours under a Shell Scholarship the following year. Raffles College and the King Edward VII College of Medicine had merged to form the University of Malaya in 1949, which meant Lee was among the first cohorts to graduate from the new university.7

Unfortunately, Lee graduated during the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), the violent guerrilla war between the anti-colonial Communist Party of Malaya and the colonial government.8 When visiting the Rubber Research Institute in Kuala Lumpur for a prospective job, Lee was taken around in an armoured car for protection. That experience brought home the gravity of the situation: “That did it. I decided if I have to go up to work in Sungei Buloh with an armoured car, I’m not going to have it.”9

He turned down the job and returned to the University of Malaya to pursue his doctorate as a Shell Research Fellow. There, he worked with Dr Rayson L. Huang on the research project “Synthesis of Synthetic Female Sex Hormones”, which Lee recounted as “an exciting project which few young men could resist”.10 He graduated in 1955 as the university’s first PhD in Chemistry.

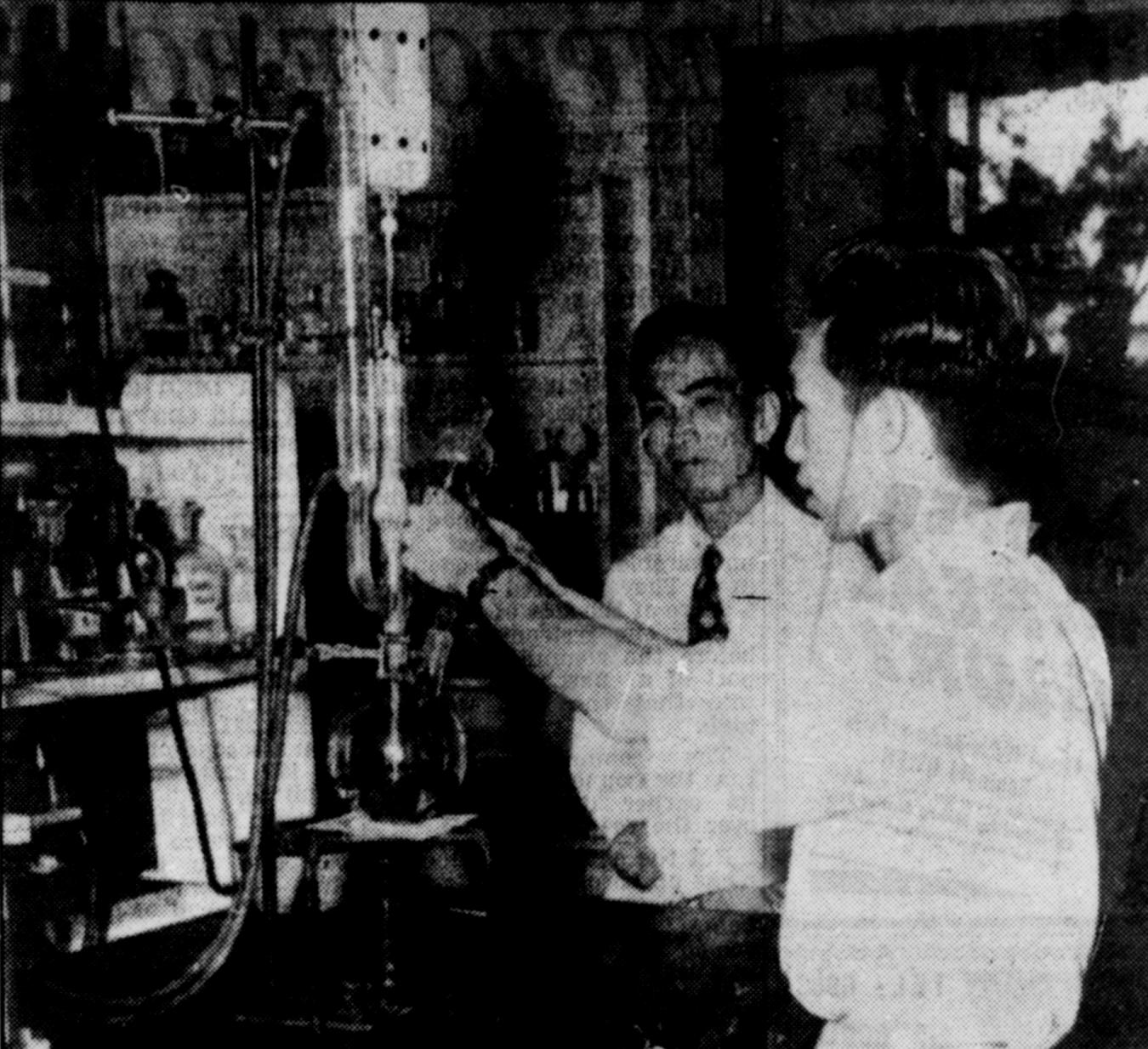

Lee Kum Tatt and Dr Rayson L. Huang working on their research project in the new laboratory at the University of Malaya, 1953. Source: The Straits Times, 14 October 1953 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Lee Kum Tatt and Dr Rayson L. Huang working on their research project in the new laboratory at the University of Malaya, 1953. Source: The Straits Times, 14 October 1953 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.Navigating Malayanisation

Lee turned down an offer from Shell to work in Brunei and went on to work in the government’s Department of Chemistry. There, he came face-to-face with a different type of politics: Malayanisation. Malayanisation was the policy of systematic replacement of expatriate staff in government by locals in the postwar years. It was a time of tension and mutual suspicion between the remaining expatriate staff and locals, which Lee experienced firsthand.

An early issue was differential treatment – Lee had been hired after completing his PhD. He was therefore appalled when an Australian woman with only a bachelor’s degree without honours was hired without going through the rigorous hiring process he had. She even commanded a higher salary than him. Lee confronted the expatriate department director and was told that his “PhD [was] not worth as much as the B.Sc. in Australia”. Lee raised the issue with the then Secretary of the Senior Officers’ Association and later Minister for Labour K.M. Byrne. The Australian woman left after a few days, ending the saga.11

Another instance was when Lee decided to try to simplify the long and tedious procedure used to analyse traces of lead and copper in wine. The chief chemist, another expatriate officer, was extremely dismissive of him, arguing that British chemists would have long discovered such a method were it viable. Lee nonetheless persisted, and the success of his new method spoke for itself, winning a newfound respect from the chief chemist.12

Lee quickly gained more administrative responsibilities, becoming a key builder of the nation’s scientific institutions. In 1959, when the People’s Action Party (PAP) came into power, Lee was appointed to the board of Singapore Polytechnic by Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye. Lee recalled his expatriate boss, the Director of Chemistry, being enraged at not having been consulted on Lee’s appointment. But Toh curtly responded that since Singapore had attained self-government, he no longer had to obtain anyone’s permission for appointments. The old colonial entitlements held increasingly little weight in the newly decolonising nation.13

Postcolonial Science

Singapore’s need to cultivate scientific talent only intensified in later years, particularly after its departure from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965. In 1967, Lee became the first chairman of the new Singapore Science Council, dedicated to improving the country’s R&D potential by cultivating both manpower and forging connections with foreign scientific bodies.14

Singapore became a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1967, and the Science Council hosted the IAEA’s first research coordination meeting in November that same year.15 As Science Council chairman, Lee opened the conference by announcing that the IAEA had agreed to provide technical assistance to set up a radio-isotope diagnostic laboratory and develop radiotherapy facilities, particularly in healthcare.16

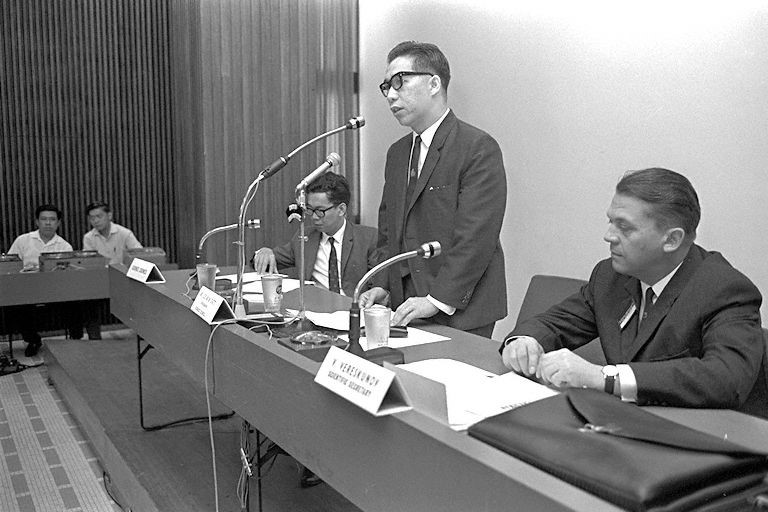

Dr Lee Kum Tatt at the International Atomic Energy Agency research coordination meeting at the Singapore Conference Hall in 1967. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Dr Lee Kum Tatt at the International Atomic Energy Agency research coordination meeting at the Singapore Conference Hall in 1967. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1969, the Science Council held the Science Ball, an event that sought to raise money for a proposed Science Endowment Fund. Nearly 500 scientists, industrialists and businessmen attended, with Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and his wife Kwa Geok Choo as the guests-of-honour. At the ball, the council awarded its inaugural gold medal to Dr T.G. Ling, an industrial chemist who had contributed to modern poultry and pig farming.17 From then on, the gold medal was presented annually to someone who had made significant contributions to science in the nation.

Lee Kuan Yew and his wife Kwa Geok Choo arriving at the Science Ball in 1969. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Lee Kuan Yew and his wife Kwa Geok Choo arriving at the Science Ball in 1969. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Promoting Standards and Research

As head of the Science Council, Lee felt there was an alarming lack of co-ordination of “national scientific efforts” between the government and private sector. As a result, he sponsored the National Conference on Scientific and Technical Co-operation between Industries and Governmental Bodies in October 1968.18 The recommendations of this conference led to the formation of SISIR in 1969. Lee served as its chairman for more than 15 years, until his retirement in 1985.19

Promoting industrial research was one of his responsibilities at SISIR – he recalled in his oral history interview that unlike the present where R&D brings researchers money, glory and social standing, in the early days of SISIR “[people] think you are mad if you do R&D”.20 To demonstrate that innovative research was possible, he helped design the famous RISIS series of gold-plated objects including orchids, eggs, walnuts, ferns, and animals from the Chinese Zodiac.21

RISIS’ products were highly popular in the 1970s and 80s. Image reproduced from “Page 28 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 18 December 1976, 28 (From NewspaperSG).

RISIS’ products were highly popular in the 1970s and 80s. Image reproduced from “Page 28 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 18 December 1976, 28 (From NewspaperSG). Dr Lee Kum Tatt with the Xu Beihong-inspired prancing horses he created, 1985. Source: The Straits Times, 19 November 1985 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Dr Lee Kum Tatt with the Xu Beihong-inspired prancing horses he created, 1985. Source: The Straits Times, 19 November 1985 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.He also led the charge to ensure that locally manufactured products met appropriate quality standards for international export, allowing Singaporean goods to be competitive abroad.22 He served as chairman of the Singapore Standards Council, the body responsible for approving new standards. In addition, as chairman of SISIR, he promoted the adoption of standards through a range of methods from training to formal certification. These methods included running national campaigns – for example, Lee was chairman of the organising committee of SISIR’s prominent “Prosperity Through Quality and Reliability” (PQR) campaign (1972–73), which aimed to promote quality-consciousness and pride among manufacturers and their employees.23

Minister Hon Sui Sen giving a speech at the closing ceremony of PQR campaign. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Minister Hon Sui Sen giving a speech at the closing ceremony of PQR campaign. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Science for the Masses

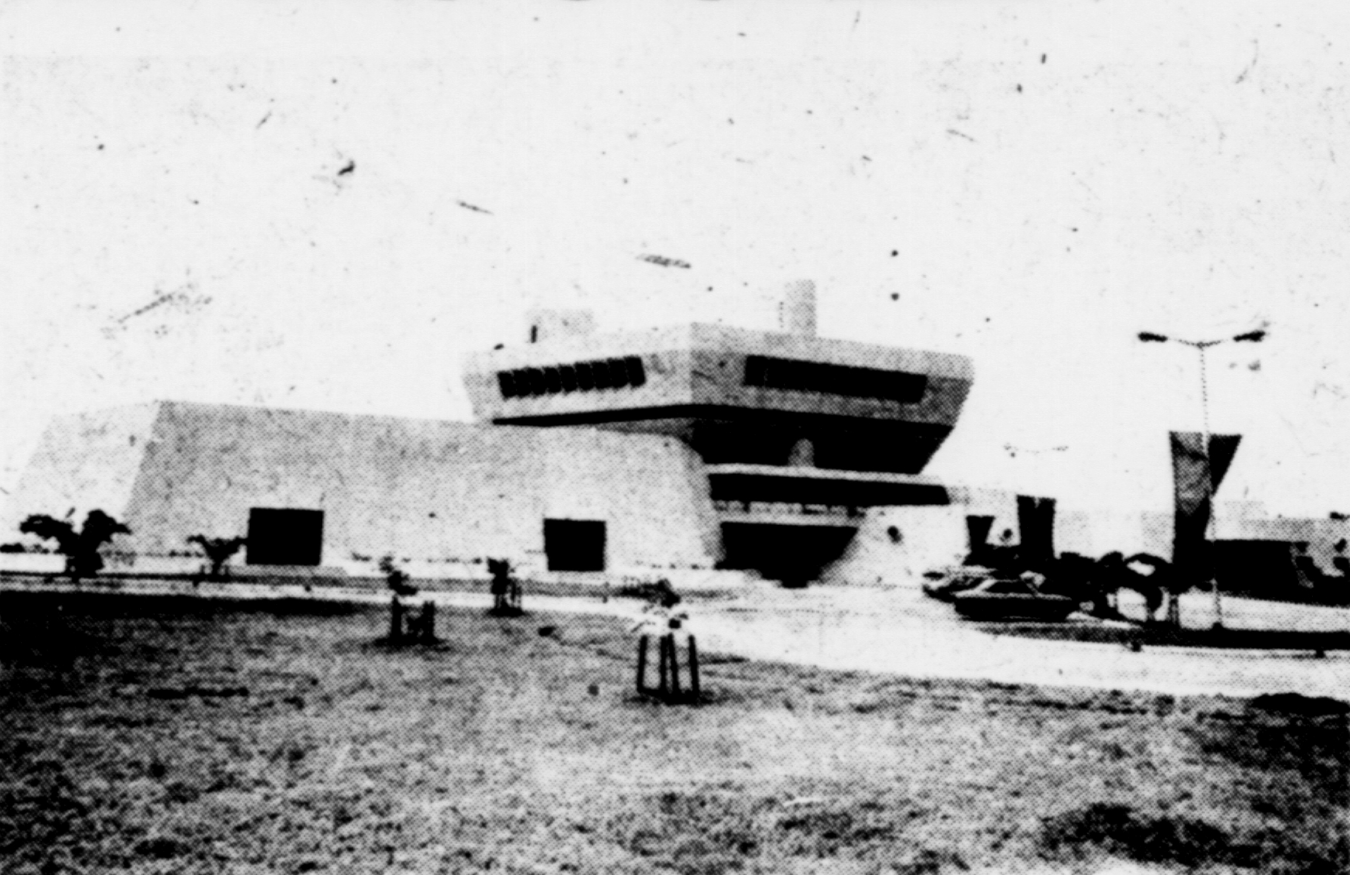

Lee was also committed to making science accessible to the broader public. When he found out that his university classmate, Rex Shelley, had been working on establishing a small Science Centre in a shophouse, Lee convinced him that it needed to be a government-funded project.24 In 1969, Lee secured UNESCO funding and personnel from the Science Museum in London to help draw up a proposal, which ultimately led to the official opening of the Singapore Science Centre in 1977.25

The Singapore Science Centre opened in 1977. Source: The Business Times, 10 December 1977 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

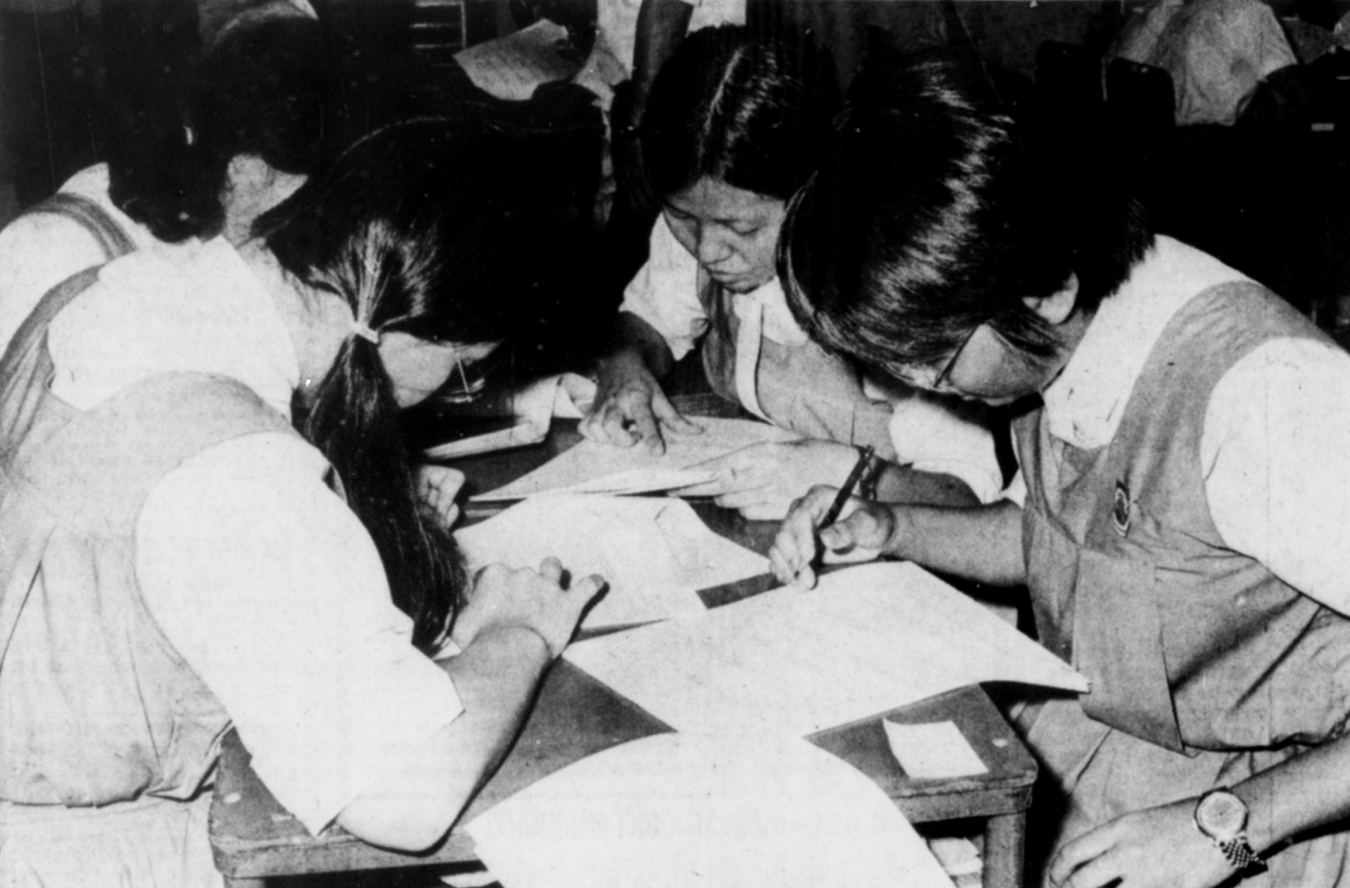

The Singapore Science Centre opened in 1977. Source: The Business Times, 10 December 1977 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.Another brainchild of Lee’s was the Science and Industry Quiz, a televised educational programme where secondary school students competed to answer general questions on Science. Teams from more than 50 schools across the country participated in the preliminary round, with the highest scoring 12 teams selected for the televised portion.26 While the contestants were students, the programme’s popularity resulted in entire families learning together and becoming more “science-minded.”27 Lee recalled one friend telling him: “[The quiz] is one show my grandfather, father and children all sat in front of the TV and watched. And all tried to answer.”28

Students from St Joseph’s Convent answering questions in the first round of the Science and Industry Quiz, 1973. Source: The Straits Times, 7 April 1973 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Students from St Joseph’s Convent answering questions in the first round of the Science and Industry Quiz, 1973. Source: The Straits Times, 7 April 1973 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.In 1979, the Science Council awarded Lee its gold medal to recognise his contributions to the “scientific, technological and industrial development of the Republic”.29 In 2005, he was awarded the Distinguished Alumni Award by the National University of Singapore’s Faculty of Science. In his foreword to Lee’s autobiography, A Fabulous Journey, Lee’s early mentor Professor Rayson Huang (then Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hong Kong) noted that Lee cherished this 2005 award above all others because “[Lee] Kum Tatt always regarded himself as a Scientist, and Chemistry held a special place in his heart”.30

Lee died in 2008, and his integral role in shaping science in Singapore has largely gone unknown and unacknowledged by the wider public. However, his dedication to creating a more scientific society has left behind a sprawling and indelible legacy through the range of institutions he built up, which continue to shape the nation today.

Sharad Pandian graduated from Nanyang Technological University with a degree in physics before pursuing a Master of Philosophy in history and philosophy of science at the University of Cambridge as a Gates-Cambridge Scholar. Sharad is interested in the history of science and standardisation in Asia. He is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library, Singapore (2022–23).

Sharad Pandian graduated from Nanyang Technological University with a degree in physics before pursuing a Master of Philosophy in history and philosophy of science at the University of Cambridge as a Gates-Cambridge Scholar. Sharad is interested in the history of science and standardisation in Asia. He is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library, Singapore (2022–23).Notes

-

Lee Kum Tatt, A Fabulous Journey (2012, Singapore: The Word Press), 145. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 540.92 LEE) ↩

-

“In Page Two: The Backroom Boys Isolate the Killer,” Straits Times, 9 September 1959, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kum Tatt, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 5 August 1993, transcript and audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000821), 22. ↩

-

Lee Kum Tatt, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 5 August 1993, transcript and audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000821), 5-6. ↩

-

“Varsity Exams to Begin Today,” The Straits Times, 30 May 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

P. Liviniyah P, “Malayan Emergency,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published May 2019. ↩

-

Lee, A Fabulous Journey, 110-111. ↩

-

Lee, A Fabulous Journey, 118-119. ↩

-

Lee Kum Tatt, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 5 August 1993, transcript and audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000821), 32. ↩

-

Science Council of Singapore, Annual Report of The Science Council of Singapore 1967 (Singapore: Science Council of Singapore), 4. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 506.15957 SCSAR). See also National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

“A-Agency Help for S’pore,” Straits Times, 7 November 1967, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Science Council of Singapore, Annual Report of The Science Council of Singapore 1969 (Singapore: Science Council of Singapore), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 506.15957 SCSAR 1969-70). See also National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Science Council of Singapore, Annual Report of The Science Council of Singapore 1968 (Singapore: Science Council of Singapore), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 506.15957 SCSAR). See also National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

“Lee Kum Tatt Resigns as Sisir Chairman,” Business Times, 14 November 1985, 1 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kum Tatt, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 5 August 1993, transcript and audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000821), 68. ↩

-

Sharad Pandian, “Singapore’s National Souvenir: The Gold-plated Past of RISIS,” BiblioAsia published June 2024, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/localicons/2024/6/risis-gold-orchid-tourism-souvenir/. ↩

-

“A ‘SISIR’ Stamp Means Quality Product,” Straits Times, 19 June 1969, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“PQR Shows What It Really Means To Think Quality In The Work You Do,” Straits Times, 17 May 1973, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Rex Anthony Shelley, oral history interview by Ghalpanah Thangaraju, 31 January 2002, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 12, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002602), 52-53. ↩

-

Lee, A Fabulous Journey, 97-98.; “When and How It All Began,” Straits Times, 10 December 1977, 41. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hard At It—Trying to Tackle 150 Queries in 30 Minutes,” Straits Times, 7 April 1973, 9 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee, A Fabulous Journey, 18-19 ↩

-

Lee Kum Tatt, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 5 August 1993, transcript and audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000821), 94. ↩

-

“The Gold Medal Winner,” Business Times, 19 May 1979, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee, A Fabulous Journey, v-vi. ↩