A Kampong for the "Grand Old Man of Singapore"

Due to development and urbanisation, Lim Boon Keng’s last home at Paterson Hill no longer exists today.

By Patricia Lin

Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957) was undoubtedly one of the most iconic figures in the history of Singapore and a prominent member of the Straits Chinese community. From his youth in the 1880s until the end of World War II, his fame as a scholar, physician, social reformer and legislator had earned him a place in history as the “Grand Old Man of Singapore”, or on other occasions, “Sage of Singapore”.1

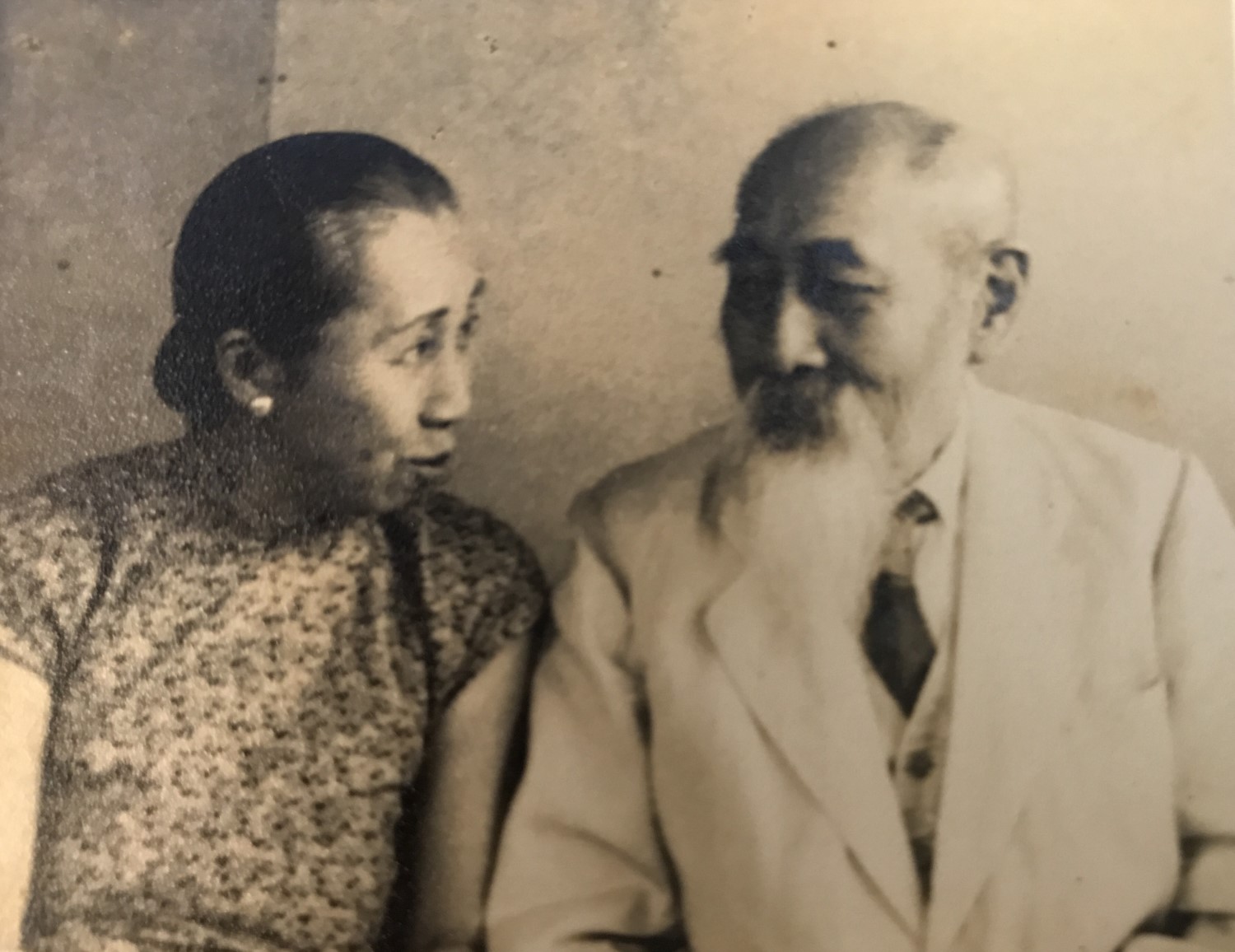

Lim Boon Keng and his wife Grace Yin Pek Ha, 1950s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng and his wife Grace Yin Pek Ha, 1950s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Much has been studied and written about Lim’s contributions in the diverse fields he was involved in and mainly served in a leadership position. He was a Chinese member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council (1895–1903; 1915–21) and a municipal commissioner (1905–06). He also co-founded the Straits Chinese Magazine (1897), Singapore Chinese Girls’ School (1899), Straits Chinese British Association (1900) and Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (1906) as well as a number of banks.2

However, the remaining years of Lim’s life between 1946 and his death in 1957 are essentially a blank. Curiously, for an individual with so much in the way of experience in legislative affairs, social organisation and public education, Lim was virtually invisible during Singapore’s birth travails toward independence and nationhood.

What has become known recently from close members of his family, however, is that in his last years, Lim assumed an unexpected role that reflected his key philosophies on humanity and social order. Between 1937 and his death in 1957, Lim lived in an antiquated, 19th-century home and became quite accidentally the head of his own “kampong”.3 This kampong, or village, stood right in the midst of the hustle and bustle of the city, an island in itself untouched by Singapore’s emergence into a new era.4

Lim Boon Keng’s mansion with the attap roof. This is a still from a home movie by Lim Kok Lian, 1972. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng’s mansion with the attap roof. This is a still from a home movie by Lim Kok Lian, 1972. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.An Attap-roofed Mansion

Lim’s kampong was located in an area that is today considered as one of the most expensive in the world. The identification of Lim’s old mansion at 1 Paterson Hill and how it evolved into a kampong is one of the hidden chapters of Singapore’s history.

The departments of Chinese Studies and Geography at the National University of Singapore have identified and mapped over 200 kampongs once found all over Singapore.5 However, the kampong with nearly a hundred men, women and children that was formerly at 1 Paterson Hill has neither been recognised nor accounted for. With the introduction of public housing in the form of high-rise flats, Lim’s kampong, like other clusters of wooden and attap thatched houses across the island, disappeared from the local landscape. As kampongs made way for concrete buildings, so too went what was known as “kampong spirit”, or gotong royong (”mutual aid”), based on a sense of community and social cohesion.

Central to what eventually morphed into Lim’s village between 1946 and 1975 was a mansion-sized house situated on a triangular lot bordered by Paterson Hill, Paterson Road and Grange Road. The huge, rambling wooden bungalow with an attap roof was a curious two-storied, 7,000 sq ft (about 650 sq m) building standing on a five-acre (20,234 sq m) compound.6

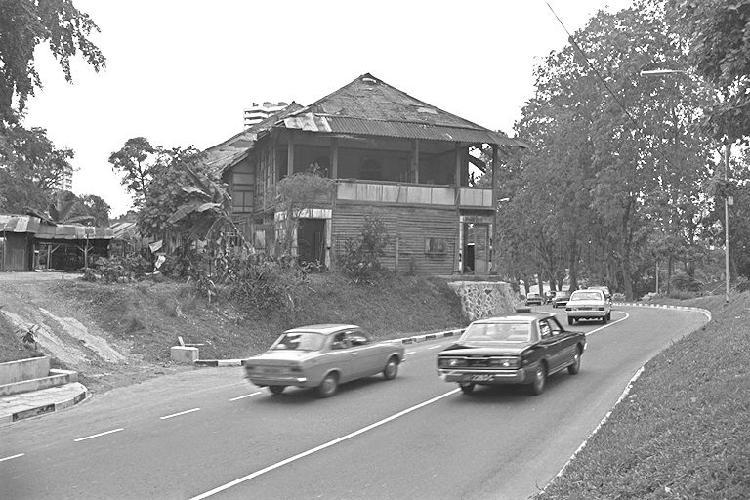

Lim Boon Keng’s mansion at 1 Paterson Hill, 1970. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng’s mansion at 1 Paterson Hill, 1970. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Chong Joo Beng, whose family was Lim’s tenant, was born in an annexed portion of the main house in 1947. According to Chong, there were some smaller houses, mostly wooden and of random design, built within the compound and sited closer to the Paterson Road side. Some of the houses were shack-like with corrugated zinc roofs”.7

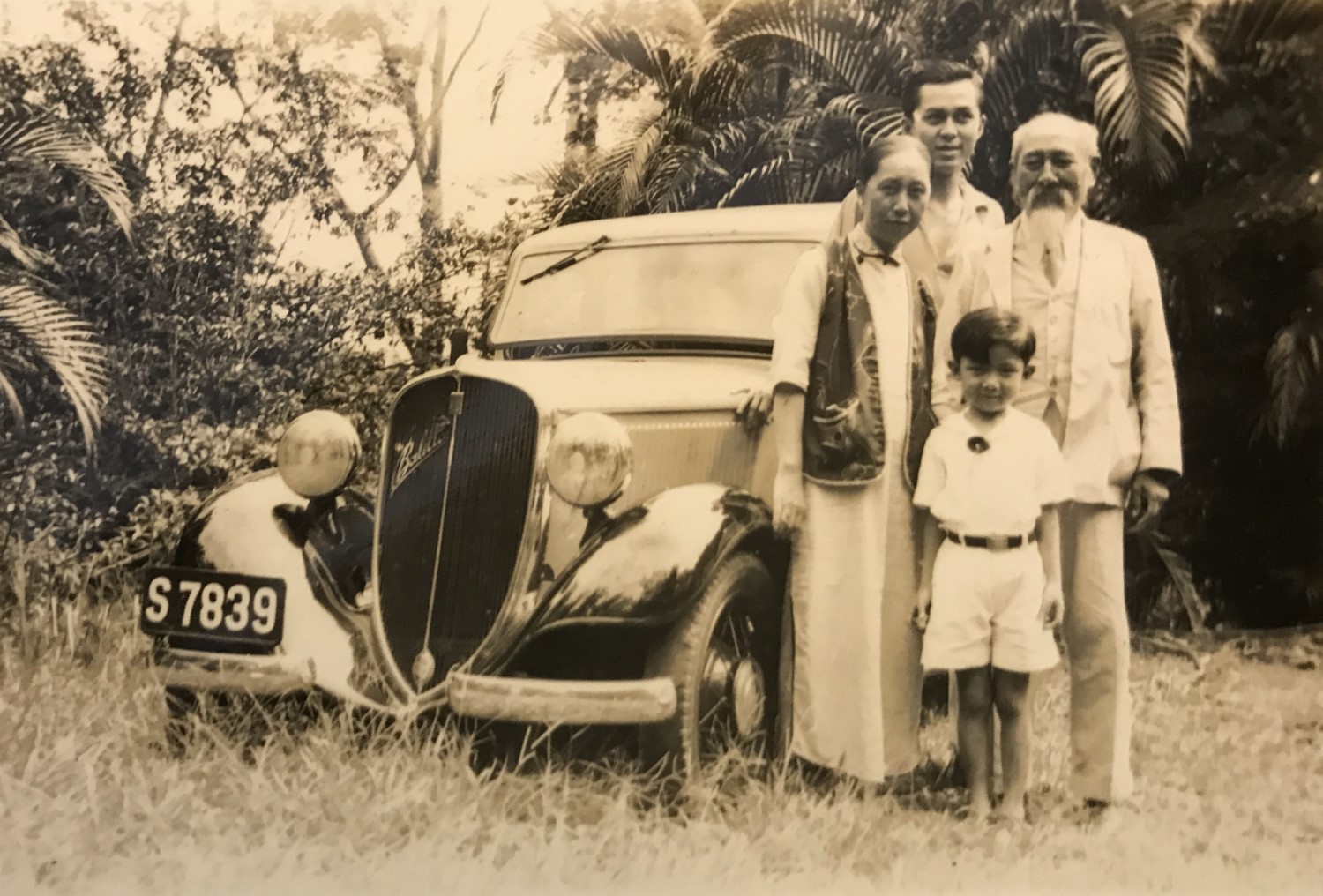

Lim Boon Keng and family in an upstairs porch of the house with the attap roof, 1935. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng and family in an upstairs porch of the house with the attap roof, 1935. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Both Chong and Lim’s grandson, Lim Kok Lian, who spent a great deal of his childhood years in the Paterson Hill mansion, recall that there were several long-term Chinese families as well as Punjabi, Malay and Eurasian families living in huts on the compound and in the mansion itself. Members of the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy also rented rooms in the main house from Mrs Lim Boon Keng née Grace Yin Pek Ha. In residence too were Lim Kok Lian’s father, the legendary auto racer Lim Peng Han, his mother and his two siblings.8

Lim Boon Keng and his wife with their son Lim Peng Han and grandson Lim Kok Lian, 1930s–40s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng and his wife with their son Lim Peng Han and grandson Lim Kok Lian, 1930s–40s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Chong and Lim Kok Lian remember that the sprawling compound had a front garden that “was reasonably maintained”, although “the hedges on the perimeter of the compound facing Paterson Hill were hardly ever trimmed”. Chong also remembers that around the area of the mansion occupied by Lim Peng Han and his family, “disemboweled motor car bodies and engine parts were everywhere to be seen”. The grounds were covered with duck and chicken droppings; the latter being the by-product of the fighting cocks that the ace race car driver bred along with the exotic Siamese fighting fish he kept in rows of earthenware and glass jars.9

Lim Kok Lian was a racing car enthusiast and also kept fighting cocks, 1953. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Kok Lian was a racing car enthusiast and also kept fighting cocks, 1953. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Surrounded by newer stately mansions with manicured lawns and a stone’s throw from the glitzy businesses along Orchard Road, Lim’s property leaned precariously into the category of an urban slum. Incidentally, one of the newer and elegant properties across from Lim’s compound, at 2 Paterson Hill, would be featured decades later in the Hollywood movie, Crazy Rich Asians.

Previous Owners

Paterson Hill itself was probably developed around 1866 and named for William R. Paterson, co-founder of Paterson, Simons & Co., a trading house. As it was common practice in those early days for roads to be named after the persons whose homes stood along the said roads, it is highly possible that Lim’s mansion was once owned by Paterson himself, just as Thomas Oxley’s home stood on Oxley Road, and Coleman Street was where George D. Coleman built his home.10

The property changed hands several times between the end of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. Previous owners included the Little brothers, John and Matthew, who established John Little & Co. department store. By the end of World War II, it had passed on to Tan Chay Yan, the rubber magnate with whom Lim had pioneered large-scale rubber planting.11

In 1937, after serving as president of Amoy University (now Xiamen University) for 16 years, Lim returned to Singapore to face another chapter in his life. Despite his connections with the banking establishment and pioneering role in the rubber industry, the worldwide Great Depression (1929–39) had left him, as it did many of his contemporaries, in deep financial difficulties.12

According to his grandson Lim Kok Lian, his grandmother once told him that the house on 1 Paterson Hill had been managed since the 1930s by Tan Hoon Siang, son of Tan Chay Yan. In recognition of the close friendship between his father and Lim, Tan Hoon Siang had “given” the attap-roofed mansion to Lim when he returned to Singapore and found himself depleted of financial resources.13

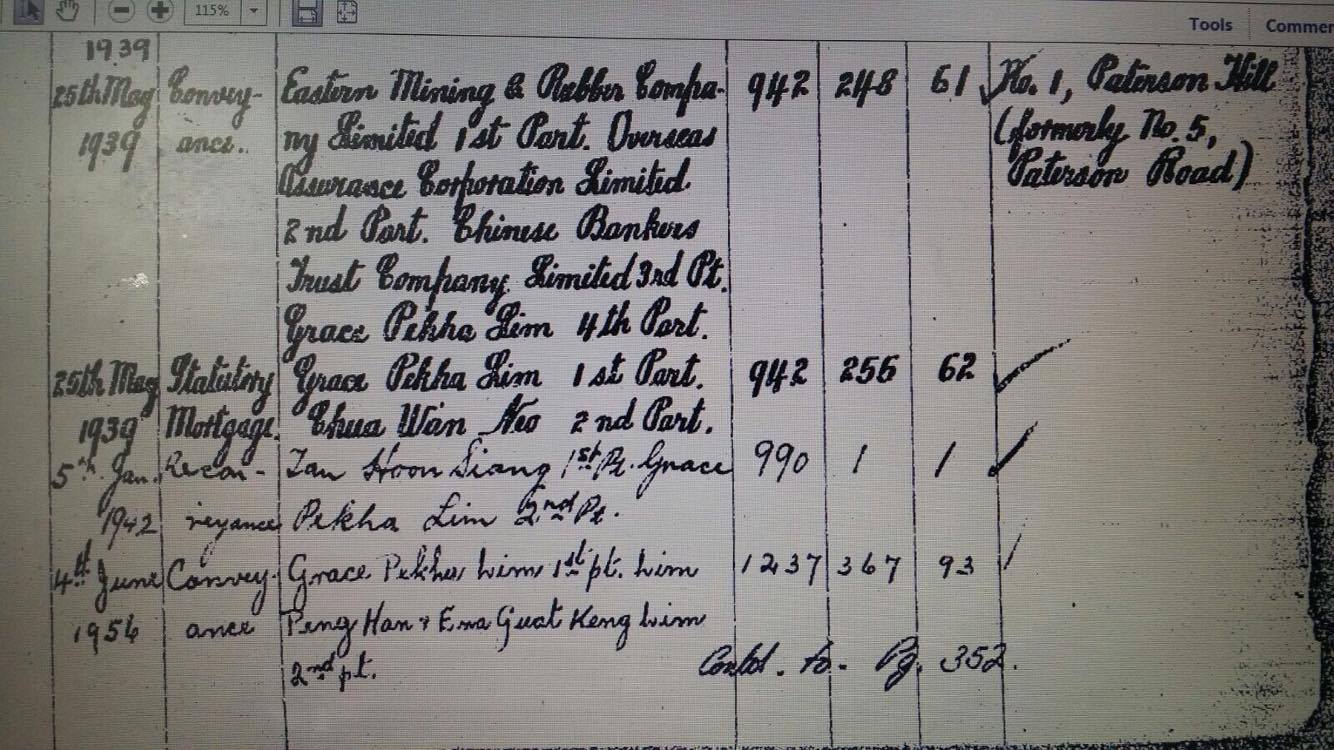

In all likelihood, the “gift” had been made by Tan Chay Yan’s wife, Chua Wan Neo, as the property was at the time listed under her name (Tan Chay Yan died in 1916). Chua was a woman well-known for her business acumen, not only in the management of the rubber plantations left to her upon her husband’s demise, but also for her real estate holdings. Later, official records reveal the official sale of the property by Chua to Mrs Lim Boon Keng in 1939.14

Deed showing sale of 1 Paterson Hill by Mrs Tan Chay Yan to Mrs Lim Boon Keng, 1939. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Deed showing sale of 1 Paterson Hill by Mrs Tan Chay Yan to Mrs Lim Boon Keng, 1939. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Matriarch of the Mansion

Aside from a period in 1942 when Lim and his wife were interned in a concentration camp on Arab Street during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), the man who came to be known as “the Grand Old Man”, or “the Sage of Singapore”, would spend the remaining years of his life in the mansion with the attap roof surrounded by his kampong as its “Sen-si kung” (“venerable sage”).15

Despite the reverence and respect accorded to him, family and former residents of the mansion and surrounding kampong recall that it was Mrs Lim Boon Keng who quietly presided over the often chaotic and unorthodox household. Over the years, 1 Paterson Hill became something of a halfway house for various progenies or relatives in need of temporary lodgings before they moved to more permanent places of domicile.16

Lim, as his grandson Lim Kok Lian recalls, lived the life not unlike any other retiree. On any given day, residents nearby would be greeted by the sight of a small, elderly man with a wispy goatee taking his walk along Paterson Hill. Immaculately attired in his tropical whites, he would often make the somewhat precarious crossing across the road to visit his friend and fellow physician Hu Tsai Kuen who resided in the Crazy Rich Asians mansion. Conversations between the two doctors were purportedly extended over more beers than probably what Mrs Lim would have permitted above the daily swig of Johnny Walker that the old man prescribed for himself.17

Lim Boon Keng with his friend and colleague Hu Tsai Kuen, 1948. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng with his friend and colleague Hu Tsai Kuen, 1948. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.Several times during the week, and accompanied by his grandson, Lim would be driven in his Humpback Dodge by a Malay chauffeur to the City Club on Cecil Street. His grandson’s role was to help him in and out of the car, and ride the antiquated lift up to the second floor of the club where he would spend the day reading the daily papers and various periodicals, meet with old friends over lunch and then nap before being taken home.18

With her husband at the City Club, which served as his daycare centre, Mrs Lim had free reign to oversee the running of the mansion and kampong residents as well as engage in the numerous charities and organisations to which she belonged. She supervised the collection of rents, and managed the wages and chores of the various servants, gardeners and handymen. She not only oversaw the health and well-being of her immediate family members, but also that of the children and families who were part of the kampong, going as far as to ensure that their schooling needs were met and arranging for jobs and suitable marriages as they grew up. In effect, Mrs Lim was the kampong’s affectionately remembered châtelaine (mistress of a large household).19

Lim Boon Keng’s wife Grace Yin Pek Ha, 1950s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng’s wife Grace Yin Pek Ha, 1950s. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.A Chapter Closes

Over time, the old building with its labyrinth of dark corridors and numerous rooms began to show signs of deterioration. Built on a gradient, the mansion had a split-level section nearer the lower end of the incline.

“The walls on the upper floor were of wood whilst those on the ground floor were of concrete,” said Chong Joo Beng. Over the years, the concrete walls of the ground floor that were painted with a limestone-based whitewash had become cracked, flaky and peeling. Likewise, the putty-like paint used to coat and weather-proof the wooden doors, windows and support beams suffered the same fate due to exposure to the elements and age. The upper-storey wood structures were painted brown, while the lower parts were white-washed.”20

As sections of the attap roof disintegrated, the holes were patched haphazardly with corrugated zinc sheets. The whole property was edged by expanses of waist-high lalang, and huge trees partially obscured the house from the street.21 Nevertheless, it was home for Lim in his last years where his clan came to celebrate his birthdays and pay their respects during the Lunar New Year.

Lim Boon Keng and his wife with their large and extended family in this picture taken at the garden of 1 Paterson Hill, 1938–39. In the background is 2 Paterson Hill, home of Dr Hu Tsai Kuen whose home was featured in the movie Crazy Rich Asians. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng and his wife with their large and extended family in this picture taken at the garden of 1 Paterson Hill, 1938–39. In the background is 2 Paterson Hill, home of Dr Hu Tsai Kuen whose home was featured in the movie Crazy Rich Asians. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.In the main dining room upstairs, Lim occupied pride of place at dinners and family gatherings. When he died on 1 January 1957, his body was laid in the reception room on the ground floor of the mansion where hundreds came to pay their last respects.22

Lim Boon Keng’s family celebrating his birthday, 1952. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.

Lim Boon Keng’s family celebrating his birthday, 1952. Courtesy of Lim Kok Lian.The old man and the mansion were products of the same era, and with his death, the mansion fell into further disrepair. The ground floor was successively partitioned, and leased to a florist and veterinary clinic.23 An extension to the main building became a rented workshop.24 Various renters cycled in and out of the premises. When the last family members and tenants moved out at around 1976, the property was sold and the venerable wooden building with the attap roof demolished.25 The site is presently occupied by a number of condominium projects.

Today, no markers identify the site as the final home of one of Singapore’s greatest citizens. Oddly enough, when the decision was made to honour him with a place name, a street and a Mass Rapid Transit station in an area with no known direct association with him were named instead.26

Dr Patricia Lin has a PhD in Comparative Literature and Critical Theory from the University of Southern California. She is retired Professor Emeritus in the Department of Gender, Ethnicity, and Multicultural Studies at California State Polytechnic University.

Dr Patricia Lin has a PhD in Comparative Literature and Critical Theory from the University of Southern California. She is retired Professor Emeritus in the Department of Gender, Ethnicity, and Multicultural Studies at California State Polytechnic University.Notes

-

Lloyd Morgan, “Singapore’s Grand Old Man (88 Tomorrow) Calls for Tolerance in This Age of Change,” Straits Times, 17 October 1956, 2; Roy Ferroa, “The Sage of Singapore,” Straits Times, 22 October 1948, 4; “Tribute by Governor as Dr. Lim Is Buried,” Straits Budget, 10 January 1957, 12. (From NewspaperSG). Lim Boon Keng was referred to as “The Sage of Singapore” as far back as the 1920s. In the recollections of Avery Mckenzie, a resident of Gulangyu, an island in Xiamen, when Lim was president of Amoy University (now Xiamen University). It was Lim’s erudition in both Western and Chinese cultures that earned him the sobriquet. ↩

-

Ang Seow Leng, “Of Towchangs and the ‘Republic Beard’: Dr Lim Boon Keng’s Life and Achievements,” BiblioAsia 2, no. 4 (January 2007): 4–9; Ang Seow Leng and Fiona Lim, “Lim Boon Keng,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 31 December 2015. ↩

-

Christine Diemer, “The ‘Grand Old Lady’ Of S’pore,” Singapore Standard, 16 August 1953, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In a blog on Singapore rock groups, Chong Yoke Lin posted her memories growing up in Lim Boon Keng’s “kampong”. She correctly identified the area as a kampong. See Chong Yoke Lin, “Dr Lim Boon Keng’s Kampong @ Paterson Hill,” Singapore 60s: Andy’s Pop Music Influence, 22 July 2015, https://singapore60smusic.blogspot.com/2015/07/dr-lim-boon-kengs-kampong-paterson-hill.html. Her brother Chong Joo Seng, in an interview with me in 2019, further described the community’s spirit of “gotong royong” that existed as spirit of mutuality as people game together toward a common good. ↩

-

De Xuan Xiong and Iain A. Brownlee, “Memories of Traditional Food Culture in the Kampong Setting in Singapore,” Journal of Ethnic Foods 5, no. 2 (June 2018): 133–39, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352618117302123. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019; Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng and Lim Kok Lian, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore, Map of the Town and Environs of Singapore, 1836, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. TM000037); “Mr. Paterson and Col. Collyer,” Singapore Free Press, 18 January 1898, 37. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Duncan Sutherland, “Tan Chay Yan,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published August 2023. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Tan Kok Guan, Chong Joo Beng and Lim Kok Lian, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Lim Kok Lian, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019. ↩

-

Tan Kok Guan, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Lim, private memoir on Lim Boon Keng and his family, 2019; “Tribute by Governor as Dr. Lim Is Buried.” ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Chong Joo Beng, interview, 2019. ↩

-

Chong, “Dr Lim Boon Keng’s Kampong @ Paterson Hill.” ↩

-

In 1920, Lim Boon Keng applied for access to an approach road to his property in “Ayer Jerneh” in the Woodleigh area. Family members cannot recall a residence at this location or whether Lim ever lived there. By the 1950s, toward the end of his life, the only property the family owned from derived rentals were in Woodlands and Pasir Panjang. ↩