Snakes & Devil’s: A History of the Singapore Grand Prix 1961–1973

Before the first-ever night-time Formula 1 Grand Prix held in Singapore, there were the Malaysian Grand Prix (Singapore) from 1961 to 1965 and the Singapore International Grand Prix from 1966 to 1973.

Common myth has it that before the Sepang Formula 1 Grand Prix in Malaysia, there was nothing in Southeast Asia to call a proper race. The roulette player had the Macau casino, Suzie Wong was the girl in the next bar and A-go-go was the rage in music. Southeast Asia offered lovely sunsets, stengahs and last vestiges of colonial rule. Behind the corrugated iron though, there existed a whole different world of CastroI R mixed with acetone, color and noise, snakes and devils, and racing.

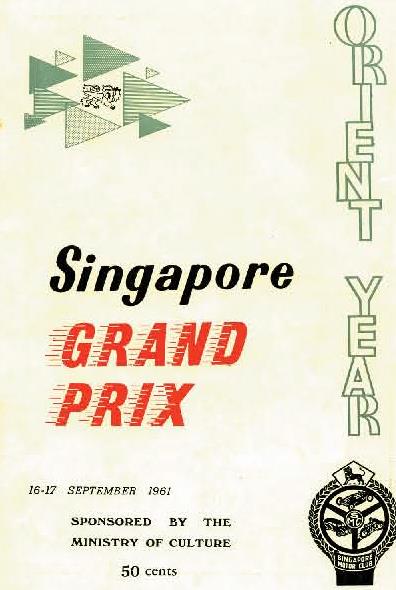

Motor racing in Singapore took off in a big way with the first Grand Prix in 1961. It was called the Orient Year Grand Prix and was held for the first time on a designated stretch of Upper Thomson Road. In 1962, the race was renamed the Malaysian Grand Prix and the Malaysian race called the Selangor Grand Prix (back when Singapore was part of Malaysia). When Singapore gained independence in 1965, the country ran its own Grand Prix in 1966 while Malaysian held two, one timed around the Singapore Grand Prix in March/April and another in September. They were known as the Malaysian Grand Prix and the Selangor Grand Prix respectively. With the onset of the European winter, and if budget permitted, the racing season in Asia would begin at Macau, move to Australia and New Zealand with the Tasman Series, and return to Southeast Asia with back-to-back Grand Prix races in Singapore, Johore, Selangor and Penang, followed by Japan.

The Malaysian Grand Prix (Singapore 1961 to 1965)

The inaugural Orient Year Grand Prix was held over the weekend of 15–17 September 1961 and an overenthusiastic crowd saw ticket sales halted by the police an hour after the races had begun. The main Grand Prix race of Sports and Racing Cars saw a mixed grid of everything from a Cooper monoposto to a Warrior Bristol (not quite the Cooper Jaguar it was listed as) - the race pitted strengths of a new streamlined Lola Climax with long range tanks; a 1955 Ferrari 500 Mondial Spider (chassis 0528 MD); a Lotus 15 with the ex-Jan Bussell Ferrari Mondial engine shoehorned into it); an Aston Martin DB3S (chassis 106); and a couple of Lotus, a Le Mans works car and a Climax. The race was run over 60 laps and was won by Ian Barnwell in the Aston Martin DB3S (which had also won in Macau in 1958). Saw Kim Thiat (who last raced in the 1953 Johore Grand Prix) had led for most ofthe race in the ex-Peter Heath Lotus 11 Climax 1100 but suffered from overheating problems. Saw however set FTD of 2:47 on lap 14, a lap time that would be bettered each year until it fell below the two-minute mark 10 years later.

The event was renamed the First Malaysian Grand Prix the following April. Motorbikes dominated the Grand Prix with 83 entries. 11 local riders had works rides from Moto Guzi and Ducati in Italy and Yamaha and Tohatsu in Japan. The track had also been widened by a few feet and completely resurfaced with “Barbergreen.”

While the organisers may have been looking forward to the event attaining international status, they were equally anxious to avoid commercialising the Grand Prix.

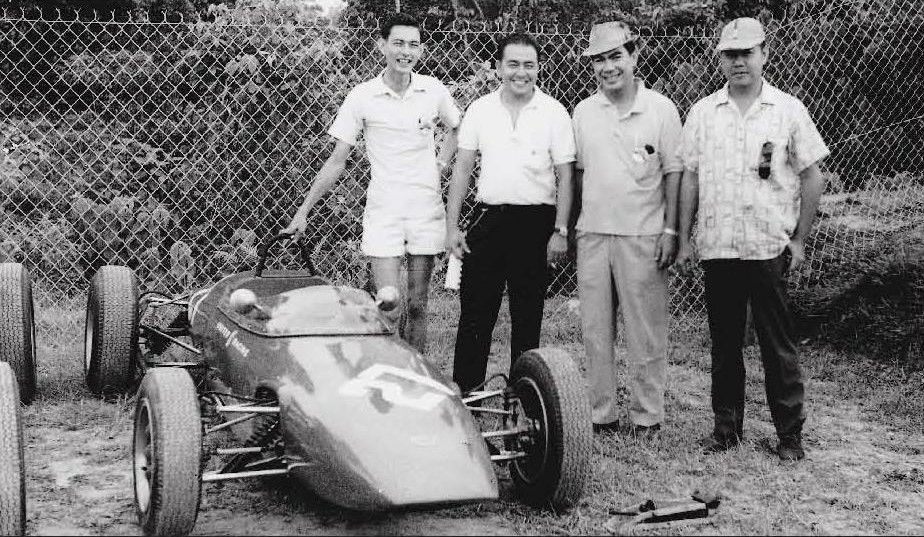

1962 also saw the appearance of the Formula Junior single-seater and the Jaguar E-Type sports car at the races. Chan Lye Choon’s Lotus 22 Formula Junior and Bill Wyllie’s DKWTojeiro received a lot of attention but it was the Jaguar E-Type that would dominate. Local boy Yong Nam Kee (known affectionately to friends as Fatso Yong) won in an E-Type while Peter Cowling’s Cooper Climax single-seater set FTD (Fastest Time of Day).

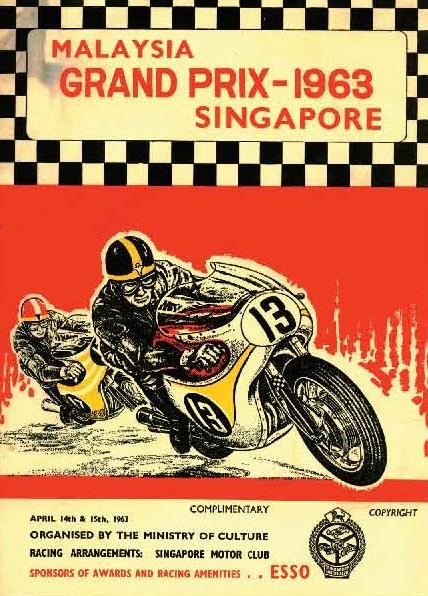

It was only from 1963 that the Grand Prix in Singapore featured in the World Motor Racing calendar. The motorcycle Grand Prix was run over the same weekend as the cars had star billing due to its international status, and notable names present included John Grace, Chris Conn, Fumio Ito and Soh Guan Bee.

The Jaguar’s dominance was being eroded by “Garagistas” and there were 12 Lotus compared to seven E-type Jaguars. While those battles raged all weekend, the Japanese quietly slipped into the country with their “works” entries - 10 600ce Mitsubishi cars for the Saloon and Tourer race.

Speeds were increasing and lap records were being bettered each qualifying session. Peter Cowling’s 1962 lap record was smashed in qualifying by Saw KimThiat, Chan Lye Choon and Angus-Clydesdale, but it was Hong Kong’s Albert Poon who won the event in his Lotus 23 with Yong Nam Kee second in his lightened Jaguar E-Type and Mike Cook, who seemed to wake up at half distance to realise that a race was on, was third in the ex-Cowling Cooper Climax. Poon, backed by Team Harper, was involved in a thrilling duel with Yong’s E-Type for over half the race. Arthur Owen, the British Hill Climb champion, had gearbox troubles yet still completed the race to finish fifth in his Cooper Climax 1960. The car was then advertised for sale at $7,000 Straits Dollars in the local club newsletter. Owen raced in a Brabham BTBA Climax 19BOcc (chassis BTB SC-1-64) for the 1964 event.

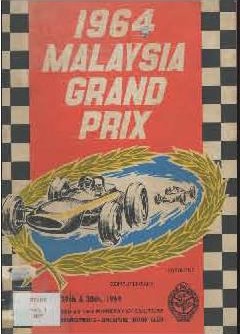

The third Malaysian Grand Prix of 1964 was rained out after seven laps. By the third lap, three of the fastest cars had been wrecked and a course marshal killed. This was also the year that saw the largest ever entry of foreign competitors in the East. More and more competitors would start to look at Asia as a stopover between the Australian and European racing seasons and the Formula Libre grid was increasingly becoming the domain of the single-seater.

In 1965 however, the only overseas competitors were Hong Kong drivers Albert Poon and Steve Holland, both racing under Richard Wong Wai Hong’s Racing Organization. The press speculated that the drop in foreign entries was due to the Singapore Government’s waning interest in holding such high publicity events in light of the Confrontation with Indonesia (which ended in 1966 after the overthrow of Sukarno).

Richard Wong had not just sponsored Albert Poon and Steve Holland with the latest Lotus 23 but had brought in some of the more exotic machinery ever seen in Asia, including the ex-Alan Hamilton Porsche 906 Carerra Spyder (which would also run in 1968). Poon, who referred to Wong as “The Wallet”, had also been planning to do the T.A.R. Circuit race in Selangor with Wong proposing that if Poon “… can make it, my team will import the latest Lotus - the VB 35 - for him to drive at KL.” The Lotus V8 never did materialise but Poon did race with his Lotus 23B.

1965 ended on a high note. Separation from Malaysia and the resulting independence of Singapore meant that big events in both Singapore and Malaysia would be competing for the same sponsorship money. The next few years would evolve to be exciting years.

The Singapore International Grand Prix 1966 to 1973

From 1966 to 1973, the renamed Singapore Grand Prix became the main motor racing event on the local calendar each Easter. The 3.023-mile street circuit was a challenge from the start. Its narrow 24ft width offered little run-off area in a sport that was increasingly seeing faster speeds.

Vern Schuppan and John Macdonald both loved it. Never one to mince his words, Macdonald describes the track: “Flowing? In places, but the 1 1/2 hairpins were not exactly ‘flowing’. Dangerous? In those days no more so than expected and certainly safer by far than Macau …. Monsoon drains, yes . … Bus stops, one after that lovely curve on the straight, and a few lamp posts. None of these things got in the way and I did not go looking for them!”

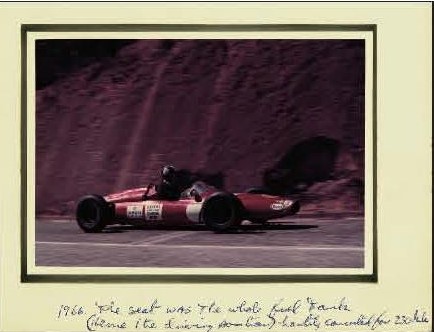

Singapore’s first International Grand Prix of 1966 saw Lee Han Seng back in the Lotus 22, Rodney Seow in an ex-1962 works Formula Junior Merlyn Mk7 fitted with a Cosworth 1500cc pushrod and four fuel tanks and a shark nose, and Hong Kong-based John MacDonald in the ex-Hegbourne Cooper-Ford Formula Junior (Cooper-Ford Mk3AI. Favourite to win was Australian Greg Cusack in a Brabham BT6 FJr (ex HenkWoelders Formula Junior chassis FJ-15-631 but the locals were ahead of the game with larger tanks for the 60-lap race, something Cusack had not prepared for.

Lee Han Seng won the main event in record time with Rodney Seow’s Merlyn Mk7 second and Tony Goodwin’s Lotus 20B third. Cusack set lap record but on lap 42, his Brabham spun into the embankment and was damaged. A total of eight track marshals aided Cusack in extricating the car out of the ditch at Long Loop and he managed to struggle on. Another competitor commented that Cusack “had turned up and just made a mince meat of absolutely everything, then lost it in the biggest way and went home.”

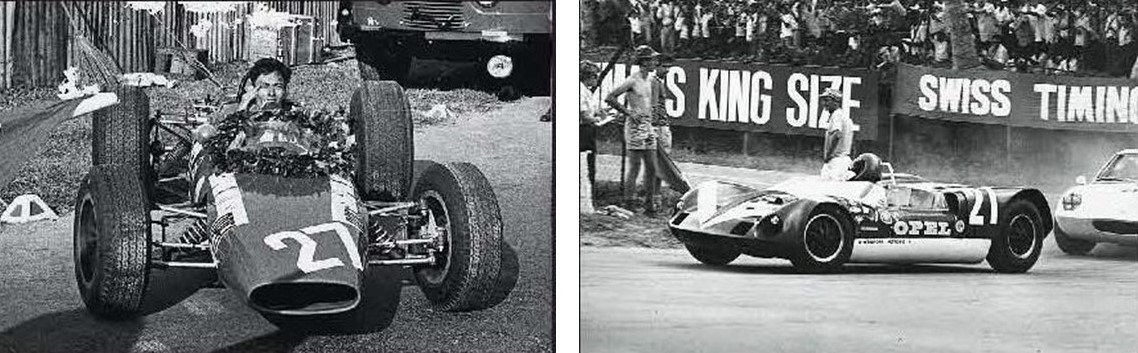

(Right) Rodney Seow in the Elva Mk7S being chased by Team Hong Kong's Steve Holland in the Lotus 47 at Range. Singapore Grand Prix 1968. Photographs by John Macdonald; LTC Ret. Bob Birrell, Rodney Seow; Stanley Leong; R.M. Arblaster.

The main Grand Prix event had graduated beyond Formula Junior and in 1967 Rodney Seow won in his new Merlyn Mk10 with a Cosworth 1600Twin Cam. Seow also made his mark by winning the Sports and GT race with an Elva BMW-Nerus (ex-Lanfranchi Goodwood lap record car).

It was not until 1968 that Australian manufacturers started to venture to the Far East. Garrie Cooper of Elfin Cars won the 1968 Singapore Grand Prix in his Elfin-Ford 600C with a FordTwin Cam. “Nobody had ever heard of Elfins; said Frank Matich. “I remember … his mechanics sent Ron Tauranac a telegram of the result. Ron sent a telegram back which read: “What’s an Elfin?”They sent another telegram saying: “A quick pixie”.

Garrie had also suggested that the Singapore Grand Prix be confined to Formula Junior and racing cars only. In addition, he proposed having qualifying times to limit the number of entrants and reduce the number of laps in the race from 60 to 50 laps. This suggestion was taken into consideration in the coming years but with a slight twist - two heats of 20 and 40 laps over different days.

Competitors were also beginning to find that import regulations for Asia somewhat cumbersome. That there had to be a prescribed number stamped on the chassis of race cars to be allowed into Singapore and Malaysia complicated matters by encouraging competitors to repeatedly use the same chassis numbers for races in subsequent years despite having different cars.

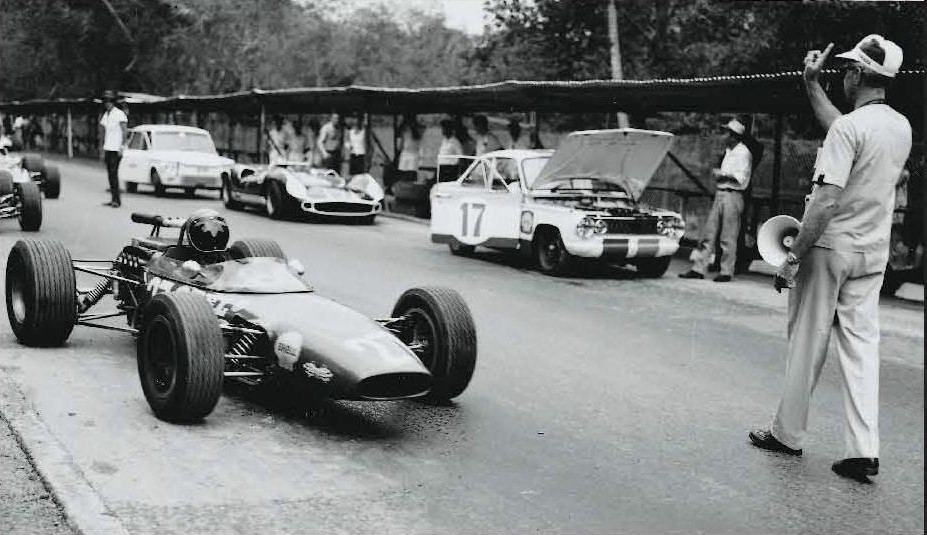

Local racers were increasingly sidelined by foreign competitors and the sponsorship they received from airlines and tobacco firms. 1967 would be the last year a local competitor would win the Grand Prix event. In 1969, Graeme lawrence won in his Mclaren M4A FVA amid some very powerful machinery on the grid. Garrie Cooper raced his BOAC Elfin 600C with a 2.5-litre Repco VB that the locals thought was a Formula 1 car, Roly Levis in his Brabham BT23C FVA, and John Macdonald in what was called a “new’ Brabham BT10 FVA (which he raced in Macau later that year). “New to everyone but built in 1964”, according to Macdonald, the BT10 was the ex-Mike Costin car that was used for the development of the Cosworth FVA engine.

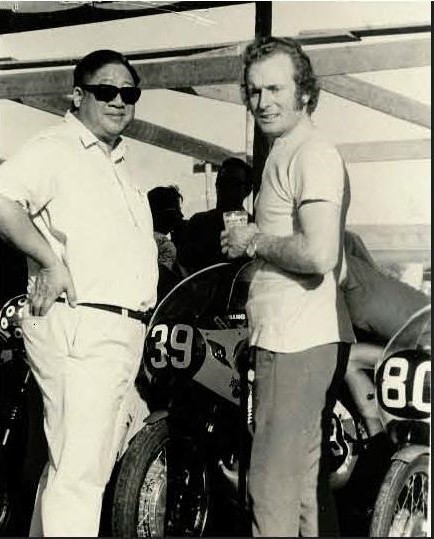

The Singapore Grand Prix marked its 10th anniversary in 1970 that saw a new sort of competitor - one that was starting to travel from farther afield - race series such as the L&M F5000 and the Can-Am in North America. Frank Matich arrived in Rothmans Team livery with his Mclaren M10Traco Chevy 4992cc F5000 car that had recently won the New Zealand Grand Prix and still was not competitive enough to make an impact or settle a score with Graeme lawrence over the Tasman Cup. The Alec Mildren juggernaut consisted of Kevin “Big Rev” Bartlett in the Yeliow Submarine Mildren with an Alfa VB (2.5-litre 1969 Macau winning car), Max Stewart with the 2-litre Rennmax-Mildren Waggott, and Malcolm Ramsay now with the ex-Gerrie Cooper Repco VB Elfin 600. Mildren was there to supervise, as was Merv Waggot, designer of the Waggott engine. Not to be outdone, Hong Kong’s Albert Poon had the ex-Piers Courage BT30 1,500cc FVA. While Matich wrecked his M10 in practice doing 160mph on the Thomson Straight, Lawrence went on to take his first win in Singapore in the ex-Amon Ferrari Dino 246T.

Lawrence made it two out of two the following year with his Brabham BT29 FVC against formidable competition in the form of the Rennmax-WaggottTwin Cam, a couple of Elfin 600s, a Brabham BT21 and a Lotus 69 (run by Ken Smith). The big change from 1970 was that the single-seaters had to follow Australian F2/Formula B rules with maximum capacity of 1600cc, and no four-valve FVAs or BDAs were permitted. This allowed Bob Birrell to run a Hawke DL2A Formula Ford that Birrell described as “understeered like a pig on wet grass, never using the same bit of grass twice”. The car finished seventh and Birrell was the first Singapore resident to finish.

With the new rules set, single-seater racing became the domain of the professional and semi-professional racer with sponsorship backing. Max Stewart arrived in the Mildren-Waggott in 1972 with the intention of selling the car after the event. For Stewart, it would be the first time he had finished a race in Asia and this would be his third try in Singapore. Winning the event and breaking Graeme Lawrence’s domination was very sweet indeed even though Lawrence had not attended the event because of a 155mph crash he had at the New Zealand Grand Prix at Pukekohe earlier.

There was a good cast for 1972 with likes of Kevin Bartlett, Max Stewart, Vern Schuppan and an underrated John Macdonald who had the ex-Graham Hill Brabham BT36-2 with a Rondel nose. There was also Sonny Rajah who “had struck up a partnership with the ex-Ronnie Peterson March 712-M” that he had recently acquired. Sonny was the local hero and looked the part with his long hair and Zapata moustache. To gain admittance into a country where long hair was associated with drugs, he had resorted to using a short-hair wig! A fellow competitor once remarked that “ … he had brilliant car control but someone … had to take him in handl Natural talent (and character to boot) … I followed Sonny for the first few laps of a Macau race and remember … that he made contact with much of Macau’s scenery; that’s a very difficult act of itself.”

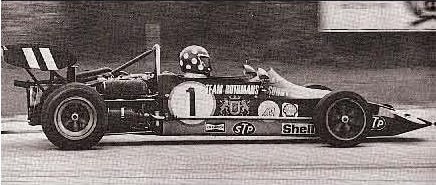

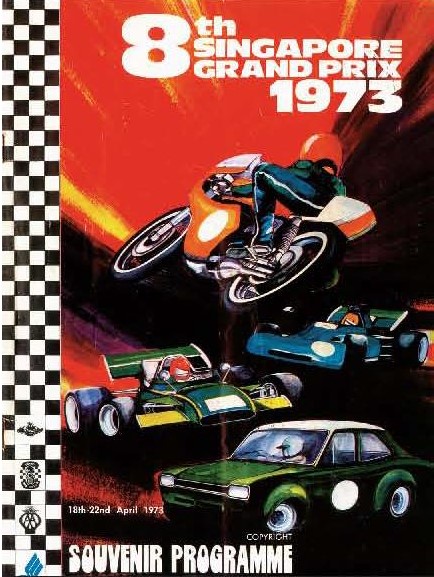

Singapore’s last Grand Prix was held in 1973 and was won by Vern Schuppan in a March-Ford 722. Schuppan vividly remembers the monsoon drains on the circuit. “lt was a fast flowing circuit - a lovely race track. No one talked about lack of run off area because we were so young then.” Of Schuppan, John Macdonald said “Vern, of course, got to the top but probably never reached the absolute top because he’s too darned straightforward, nice, honest, and all those other good things that come up all too rarely.” The March 722 was the same one Schuppan had driven in 1972 but with up-to-date modifications.

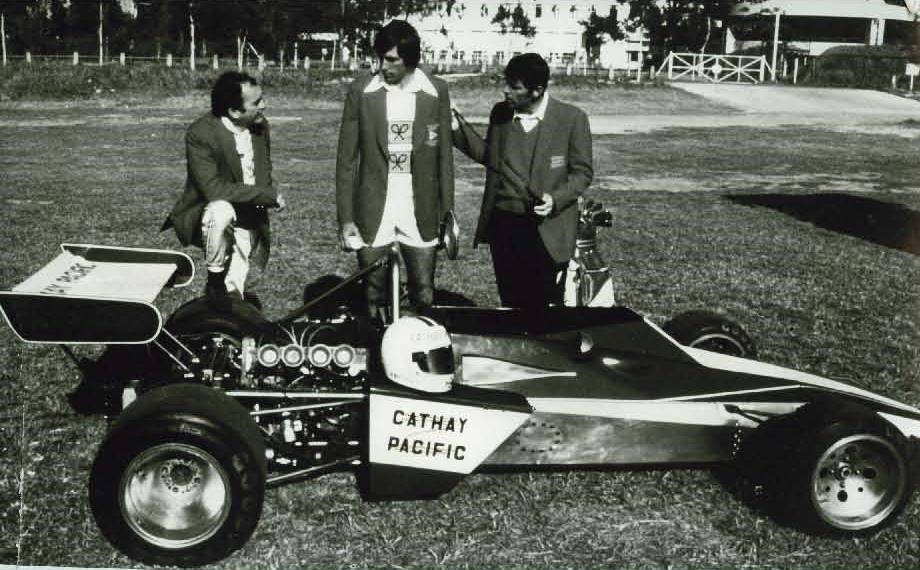

Cathay Pacific-backed John Macdonald was another favorite and had a brand new Brabham BT40 delivered to him in Singapore ahead of the race. Macdonald called the BT40 a “magic car with a big BUT”. The team had a terrible time of it with fuel pick-up problems. A letter to Bernie Ecclestone (who by that time owned Brabham) resulted in a PR reply to say how he was behind them all the way! Once sorted, the car was a profilic winner in Asia.

In the race, Vern Schuppan was leading Malcolm when Ramsey’s Birrana at one point when the March kicked up some rocks resulting in a punctured fuel tank for the Birrana. Angus Lamont, who assisted John MacDonald, remembers this incident (Ramsey) very soldiered well” …. on and until Malcolm the pain of the petrol burning [him] forced him to retire”. In reference to how lightweight the Birrana was built, Macdonald said that” … the car was full of holes … it was as if somebody had leveled a sub-machine gun against it.” Fittingly, Leo Geoghegan’s Birrana 273–007, the works car, set the final lap record for the circuit.

There are few street races that have survived around the world. The modern-day racetrack is a fenced edifice with so much run-off area you could build a shopping complex between track and stands. With her superb organization and hospitality the Singapore Grand Prix outdid everyone in the region, yet the the track itself had a reputation for oil trails left on the roads from the local diesel-run buses, monsoon drains, bus stops and lamp posts. Macau hade the South China Sea, Singapore had the more intimidating monsoon drains!

The track was 3.023 miles with a fast undulating one-mile stretch called the Thomson Mile (actually the start of what was then Nee Soon Road) and a series of esses on the back section linked by hairpins at either end (what is still Old Upper Thomson Road today). The start-finish line was laid on the main straight. On any given day, the two-lane blacktop would serve as one of the major trunk roads for heavy traffic. On the right of the main straight were fruit plantations and on the left were new housing estates and industrial parks sprouting up.

The bend halfway down the straight after the start-finish line was known as The Hump. This had a false apex as it sat on the turn-in that saw cars lift off the ground at high speed. The left side of the road cambered oddly which caught Australian Frank Matich off guard during practice in 1970 leading to an altercation with a bus stop which ruined his weekend and his Mclaren M10 Traco Chevy F5000. Immediately after The Hump came Sembawang Circus 1969 or The Hairpin, dangerous because cars approached flat out (chicaned till 1969 in an effort to preserved spectators and the Cabinet sitting on the VIP stands).

The esses were made up of a number of sections heading uphill towards Pierce Reservoir following Circus Hairpin. The first, Snakes, consisted of a series of four bends. This was followed by Devil's, a rounded-off V-bend impossible to pass yet offering a very good vantage for spectators. Devil's caught out everyone out at some point. After Devil's came the Long Loop, a right hander that would see fuel and oil surges in engines - particularly bad for Minis with poorly-designed oil sumps.

Peak Bend followed Long Loop headed where television and radio teams positioned themselves. The circuit then headed downhill right to Range Hairpin where one could see all that was taking place in the pits to good effect. This was followed by a hard right onto Thomson Mile past the pits known as Signal Pits. Pit entry was after Range Hairpin.

One would generally require around 24 gear changes per lap, or 1440 gear changes if you were doing the 60 lap main event (from 1970 it was split into two events of 20 and 40 laps over two days). In reference, a modern F3000 car on the Monaco circuit would require about 30–40 gear changes per lap.