Heat and Rain in the Poetry of Khoo Seok Wan

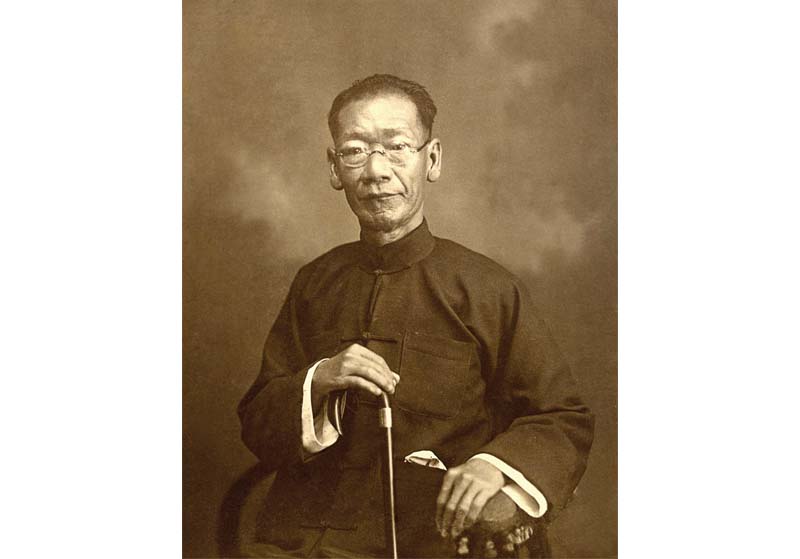

Khoo Seok Wan in his later years. All Rights Reserved, the late Khoo Seok Wan Collections, National Library Board, Singapore 2013. Courtesy of Ong Family, descendents of Khoo Seok Wan.

Khoo Seok Wan in his later years. All Rights Reserved, the late Khoo Seok Wan Collections, National Library Board, Singapore 2013. Courtesy of Ong Family, descendents of Khoo Seok Wan.Khoo Seok Wan (1874–1941), the multi-talented Chinese scholar and poet is considered by many to be one of Singapore’s best and most prolific literary pioneers. Khoo was a man of many hats: a practical Confucianist, staunch Buddhist, passionate newspaperman and an ardent reformist, who at the same time was known for his chivalry and reputation for living life to the fullest.

Born in Haicheng in Fujian Province, China, Khoo settled in Singapore with his parents when he was eight years old. His father, Khoo Cheng Tiong, who was in his twenties when he arrived in Singapore, was a successful rice merchant and a prominent community leader.

Educated in the Confucian tradition, Khoo Seok Wan returned to his hometown in China when he was 15 to prepare for the all-important Chinese imperial examinations. In 1894, he passed the provincial level of the examinations and attained the level of juren (举人), which meant that he qualified to sit for the next level conducted by the central government in Beijing the following year. However, Khoo was unsuccessful in his attempt, and in 1896 he returned to Singapore somewhat disheartened.

Khoo and his siblings came into their inheritance after their father’s death and Khoo stayed in Singapore for good. Like most Chinese literati of the day, Khoo led an extravagant lifestyle during his early years, enjoying life’s many pleasures. Besides managing the family business, he advocated the promotion of culture and education, founding poetic societies such as Lize and Huiyin, and establishing the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School with prominent contemporaries such as Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang. He even edited Thousand Character Classics: A New Version (《新出千字文》), probably the earliest existing original Chinese preschool text in Singapore.

As a newspaperman and journalist, he founded the newspaper Thien Nan Shin Pao (《天南新报》) in 1898, became chief editor for Cheng Nam Jit Poh (《振南日报》) in 1912, and was appointed editor for the literary supplement of Sin Chew Jit Poh (《星洲日报》) in 1929. Politically, Khoo supported the reformists, in particular, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, contributing financially and helping out where he could.

As a result of his extravagant ways Khoo went bankrupt when he was 34; this was a major turning point in his life and led him to live the rest of his life frugally. As the Chinese poetry pioneer of Nanyang, Khoo had written more than a thousand poems in the traditional form. His works include Notes of Khoo Seok Wan《菽园赘谈》, Collected Poems of Xiao Hong Sheng《啸虹生诗钞》, Five Hundred Stones: A Collection of Literary Criticism《五百石洞天 挥麈》, including his poetry collection Collected Poems of Khoo Seok Wan《丘菽园居士诗集》 edited by his family.

Tropical Heat

Singapore, known as “Sin Chew” or “Xingzhou” (星洲) in Khoo’s day, is the same tropical island it is today, experiencing uniform temperatures throughout the year, with high humidity and abundant rainfall.1 Records from the 19th century reveal the weather to be quite unexciting: “hot and no chill”, “sunny at times, rainy otherwise”, “rain at times but no downpour. The sun rises [at] 5am, starts setting from 5pm, consistent through the year. Hot in the day, cool at night, the same through the seasons”, “sun and rain are well regulated, sunny three days in five, rain in the other two, never long draught nor prolonged rain”.2 All rather prosaic and humdrum, but when reinterpreted poetically by Khoo, readers are able to experience the tropical climate in vivid detail and in ways hitherto unknown. The unconventional descriptions in Khoo’s poems depict the multifariousness of the weather accurately and at the same time open up a window to the poet’s innermost thoughts and feelings.

The intense heat was, of course, a notable feature of Sin Chew‘s tropical climate, and Singapore was thus given the moniker “Yanzhou” (炎洲), meaning “hot island”. The heat was unbearable, especially in the absence of rain and modern conveniences such as electric fans and air-conditioning that we enjoy today. The Westerners living in Singapore felt the oppression of the weather, as did Khoo.3 He felt trapped and helpless as expressed in his poems, “nowhere to hide in the flaming heat”,4 using hyperboles such as the “boiling sea”, “scorching moon” and “burning river” to bring his experience to life:

Bitterly hot for consecutive nights

The heat evaporates all water in every corner

Clear ripples shining the jade-green Nymphoides

The bright moon scorching red pearls

苦热连宵甚,炎蒸遍水隅。

清波明翠,月灼红珠。5

It seems like the summer has not ended

The awe of the heat still accumulated within the island

Half the river seems burning in red

Thousands of trees enveloped in green

犹未销残暑,炎威积岛中。

半江红似烧,万树绿交笼。6

This helplessness resulting from an inescapable situation made the poet lose hope in the gods (老天) – “useless deity in heaven stimulating poetry” (天公无用把诗催) – the only consolation from the deity was probably the material that Khoo was able to use in his writing and poetry.7

Tropical Rain

Apart from the heat, “wetness” also features prominently in Khoo’s poems. Let’s take a look at his description of the wet season:

In the midst of the rainy season

The hot island is experiencing a spike in chill

Seeing the starving rat jumping around the stove

The freezing fly seeking refuge through the curtain

殊方当雨季,炎岛陡寒增。

窥灶腾饥鼠,穿避冻蝇。8

The wet season comes along with the winter moon

A sudden change in weather in the hot island

The swallows in the roof move seeking refuge

The croaking frogs in the trees know the rain

湿季随冬月,炎洲候忽差。

移巢避燕,知雨树鸣蛙。9

Both poems are written in similar styles, highlighting the scale of the tropical downpours and their sudden onset, causing the usually hot island to experience a sharp drop in temperature. The reader is left with an acute sense of how uncomfortable this is and animals, which as the sensitive and observant poet shares, are not spared either – the rats, flies, swallows and frogs are described as hungry and freezing, dodging and croaking.

In other poems, we see “winter in the hot island experiences rain for consecutive days” (炎洲冬序雨连朝),10 “long days of continuous rain” (长日连番雨)11, “in the beginning of winter, the rain never stops” (冬首雨连绵), “among the clouds in the hills, the screen is suspected to be heavy” (山 云疑幕重)12 – all pointing to the prolonged rain in Sin Chew and how thick and weighty the clouds could get.

Khoo also recorded some fascinating and peculiar climactic occurrences, for instance, “on the island, there is always this unusual phenomena that the sun and rain, dry and wet, are separated at one place at the same time”. Many Singaporeans will be familiar with this experience, particularly while travelling along an expressway in the pouring rain, and then suddenly transiting into dry and sunny weather, a distinct veil of rain separating the two as it were. Khoo materialised this observation with two poems titled “Inspired by the Sunny Rain” (《晴雨即事》): “the front hall receives heat while the back is cool/ the cloudy and sunny are separated in half without a wall” (前堂迎燠后堂凉,分半阴晴不隔墙), “the occasional rain blocks the southern travel out of the sudden/ splitting the north and south in a sunny day/ it has always seemed borderless by a glance/ but suddenly, it feels like it has been halved with boundaries” (时雨南行忽阻前,截将 南北昼晴天。由来一望原无界,陡觉中分自有边), (何须寒暖随朝暮,燥湿同时感自然).13

This also occurred in mountainous areas as is described in in another poem “Description at the Sight of the Sunny Rain, Requesting a Poem in Reply from Ven Chi Chan” (《晴雨同时, 触目述怀,索痴禅开士和》): “Rain in the southern mountains but not in the north” does not seem as intriguing.14

In fact, Khoo’s poems about the weather are at their best when he writes about scenes when the rain has just stopped. He wrote, “A rain in the morning brings the chill from the sea” (一雨朝来海 气凉),15 “the rain just past and summer feels cool” (一雨才过觉夏凉),16 “the roof turns green after the rain, where the doves play in the sun/ the little courtyard starts to feel the chill” (雨馀 绿闹晴 鸠,一味凉生小院幽)17, “the accumulated rain sends cold flood in the wind” (积雨通寒汛飘风).18

The following two poems offer a more holistic post-rain view of Sin Chew:

Winter in the hot island experiences rain for consecutive days

When the fog sets apart the vegetation stands tall

Under the dancing moon the jade-green coconut trees kept in close order

The rainbow drinking from the stream leans over the long bridge

Entering the smog without having the straw raincoat prepared

Ploughing together by the side of the field

I can plough barefooted

Shall meet companions in times of flooding

炎洲冬序雨连朝,宿雾开时草木骄。

舞月翠椰排密阵,饮溪红霓卧长桥。

渔蓑未办烟中入,耘杖相期陇畔招。

脱足耕吾尚可,倘容沮溺遇同侨。19

The rain shows compassion after the prolonged heat

Feeling the shower in front of the window

Within the winding dock a lonely flower stands bright

Through the cold smog a heron flies

久热雨相怜,临窗一洒然。

孤花明曲坞,只破寒烟。20

And amidst all this chill during and after the rain, it is alcohol that keeps the poet warm. He says, “How best to defend from the chill?/ Little sips of strong wine” (敌寒何物最?小酌有醇醪).21

Other Influences

In the “rain” poems, other aspects of the poet are revealed, such as his Buddhist and Zen beliefs, both of which are common themes in his writing. These influences are also reflected in his work, for instance, while admiring lotus and bamboo in the garden after the rain he felt “this celebrated scene qualifies to be presented to Buddha”.22

Some “rainy” poems relate to his life in his later years. Khoo’s poetry during this period are mainly scenic descriptions, written in a relaxed tone. For instance, in “After the rain on a Summer’s Day” (《夏日雨霁》) the poet felt that the birds spoke “in a happy tone” (含乐意), the clouds “played with sunlight” (逗晴光), and “the senior villagers without any headdress are sitting at the moment/ using flowers and banana leaves as clothes calling it their attire” (此时野老科 头坐,卉带蕉衫称野装).23 Other examples include “Discussing agriculture with the island farmers during free time/ plowing through the green field quick and deep” (闲与岛农谈圃学,扶犁绿野快深 耕)24, “seeing rain after prolonged heat” (久热得 雨), and “lying in bed listening to the noisy magpies/ one can be accommodated for being free and relaxed” (高卧绳床听鹊噪,世容无事作闲人).25

Among these later works, we can sometimes sense his loneliness, such as in “Scene in the Rain” (《雨中即景》) where he celebrates having the company of poems in old age and sees himself as “[f]ortunate to have poems to expend the everlasting days/ not feeling the aged loneliness though retired and idle”.26

Khoo’s poetry transcends time and space and vividly brings the weather conditions of late 19th- and early 20th-century Sin Chew to life. His tactile and realistic descriptions go beyond the visual, encompassing elements of sound, sight and touch. The beauty of traditional Chinese poetry shines through in Khoo’s works: the monotonous climate of the tropics is painted in glorious brushstrokes of colour and brought to life, exciting our senses, reminding us to be more sensitive to our surroundings and to engage nature in more visceral ways.

All English translations for the poems and their titles were provided by the author.

Ho Yi Kai is a Senior Editor with World Scientific Publishing Co, Manager and Assistant Editor-in-Chief of World Century Publishing Corp, and the Assistant Director of Pioneers’ Memorial Hall. He obtained his BA from Peking University, and MA and PhD from Nanjing University. He was a researcher for the recent “Khoo Seok Wan: Poet and Reformist” exhibition organised by the National Library.

REFERENCES

丘菽园居士诗集》. Call Number: Chinese C811.07 CS 饶宗颐编 [Rao, Z.Y.B.]. (1994). 新加坡古事记. 香港 : 中文大学出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.57 JTI)

Wise, M. (2008). Travellers’ tales of old Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Available via PublicationSG)

National Environment Agency. (n.d). Weather/Climate information. Retrieved from National Environment Agency website.

National Library Board. (2021, March 22). Qiu Shuyuan biography. Retrieved from Web Archives Singapore.

NOTES

-

National Environment Agency. (n.d). Weather/Climate information. Retrieved from National Environment Agency website. ↩

-

《新嘉坡风土记》, 见饶宗颐编《新加坡古事记》,香港:中文大学出版社,1994年,页167。 ↩

-

… it is the moist heat which makes it unpleasant (p. 125). (2008). In M. Wise, Travellers’ tales of old Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Available via PublicationSG) ↩

-

《二月七日早,枕上闻雨》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页3。 ↩

-

《二月十六夜,东滨苦热》, 同上。 ↩

-

《八月苦热》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页26。 ↩

-

《苦热不雨,戏为俳体》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页19–20。 ↩

-

《岛上雨季》其一 , 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷六, 页11。 ↩

-

《湿季》其一 , 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页46。 ↩

-

《岛上雨后,极目写怀》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷六, 页14。 ↩

-

《连番雨》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页57。 ↩

-

《冬首雨》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷六, 页16。 ↩

-

《晴雨即事》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页22。 ↩

-

《晴雨同时, 触目述怀,索痴禅开士和》, 同上, 页23。 ↩

-

《雨后极目》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷二, 页18。 ↩

-

《夏日雨霁》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页7–8。 ↩

-

《雨过即事》(自注:在禧街振南社作), 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷四, 页4–5。 ↩

-

《积雨》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷二, 页11。 ↩

-

《岛上雨后,极目写怀》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷六, 页14。 ↩

-

《雨后感咏》其一, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页42。 ↩

-

《敌寒》, 同上,页57。 ↩

-

《小园雨过,起视荷竹,生趣盎然,漫赋一首》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》初编卷二, 页11。 ↩

-

见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页7–8。 ↩

-

《对雨作》, 同上, 页52。 ↩

-

《久热得雨》, 见《丘菽园居士诗集》二编, 页3–4。 ↩

-

同上, 页15。 ↩