Dr Carl Schoonover on Being SURE

In this exclusive interview, Dr Carl Schoonover shares how the brain processes information and the importance of Information Literacy and the S.U.R.E. ways in the corroboration of information and data.

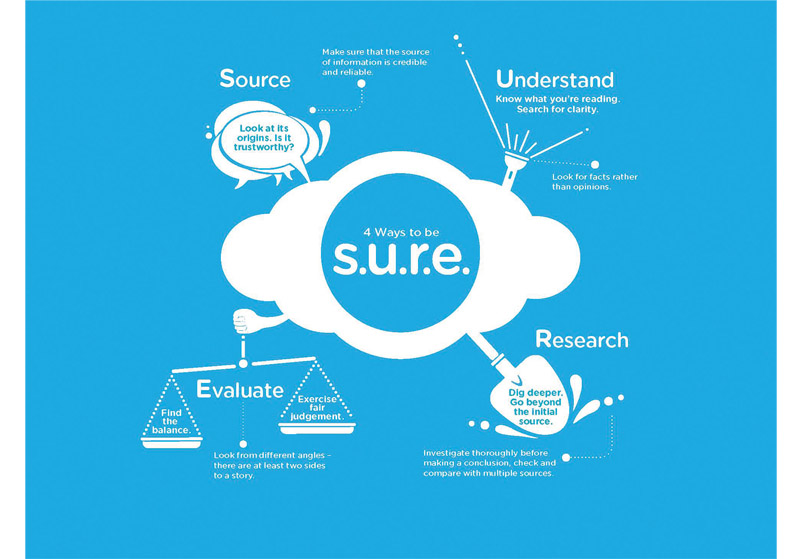

The National Information Literacy Programme promotes four simple steps – Source, Understand, Research and Evaluate – to assess information.

The National Information Literacy Programme promotes four simple steps – Source, Understand, Research and Evaluate – to assess information.Dr Carl Schoonover, a neuroscience postdoctoral fellow at the Axel Laboratory at Columbia University, was a keynote speaker at S.U.R.E. Day held on 14 November 2013 at the National Library as part of its National Information Literacy Programme (NILP). The NILP seeks to simplify and promote information literacy, emphasising the importance of evaluation and discernment of information sources.

In essence, S.U.R.E represents four simple steps to assess information: Source, Understand, Research and Evaluate. S.U.R.E encourages people to check if their sources are reliable, delve deeper into available alternative sources and materials, and evaluate the information based on their findings.

In this exclusive interview, Dr Schoonover shares how the brain processes information and the importance of Information Literacy and the S.U.R.E. ways in the corroboration of information and data.

You have a background in philosophy and then decided to pursue a PhD in neuroscience. That seems like a remarkable shift where you moved from a general and abstract study of the mind and knowledge to a very specific, scientific study of the nervous system. Why or what inspired you to pursue a doctorate in neuroscience?

Philosophy, of course, is interested in many other things than just the mind, but that was perhaps the most interesting thing to me as an undergraduate in college. I felt eventually, as I got to know the field a little bit better, that we were asking a lot of questions in philosophy that needed answers from science. And I grew increasingly dissatisfied with the inadequacy that philosophy, as a study, presented.

Philosophy was unable to offer empirical answers to explain the processes that define our consciousness and we can theorise about the state of the mind, the nature of consciousness, and how we decide, but what was lacking were facts about the machinery, about the process, and how these things happen in the nervous system. And so I grew frustrated with certain aspects of philosophy and decided to literally get my hands dirty and become an experimental research scientist.

Now, that is not to say that philosophy does not have anything to offer about how we look at the brain and how we look at the mind. And, certainly, I think the philosophers who are making the most progress today are the ones who are using information from neuroscience research and then drawing conclusions about philosophy or in philosophy from that information.

But for me personally, it felt more exciting, at this moment, at the beginning of the 21st century, to jump into what is ultimately a very young field, which is neuroscience, something that has only been around for a century – which in science, is nothing.

Information literacy is defined as the ability to know when there is a need for information and the ability to access, evaluate, use and create information in an effective and responsible manner. How do you see the process and application of information literacy as relevant to how the brain processes information?

The brain’s function, basically, everything that it does, is to process information. The brain is an extraordinarily complex structure where information overload is really the starting point. As neuroscientists, we are beginning to have a grasp on what exactly is going on when information is processed by our nervous system in everyday life.

The brain is the ultimate arbiter of our perceptions, our interpretations and our decisions, our moment-to-moment evaluation of the world around us. The brain, then, is in the business of processing information coming in and producing what it deems to be the right response to this information. And so one way of thinking about the brain, is that it is a structure in which information is constantly flowing, and this is very similar to the process and application of information literacy.

Our problem in life is to take information in from the world, make sense of it, and then behave in the best way possible given that information. And often, that information is very fuzzy and dirty; we are not getting the full picture and we need to make decisions based on very incomplete data.

And so the brain really, is designed – from the standpoint of evolution – to make sense of very fuzzy data sets and to try to understand the world as best as possible, and when things are missing, it will sometimes even fill them in for you. A simple example is optical illusions. When we see an illusion, we think something is there that is not actually there and that is the brain getting tricked into doing what it does. Normally, we are trying to extract meaning all the time from what is being presented to us. We can take this metaphor more broadly to how we access information. Very often, we are only getting a very limited perspective because there is only so much time to present it. So we create stories, about how to make sense of all this in our heads.

The process and application of information literacy is contiguous to what the brain does to help us evaluate and mediate information as best it can. The world is so uncertain, and there’s so much information coming in, some of it good and some of it bad, it has to solve this problem for us all the time.

NLB’s S.U.R.E. campaign is about bringing information literacy awareness to the man in the street, where we condense the information-searching process into four steps – Source, understand, Research and Evaluate. How would you explain the information searching behaviour and processes to the man in the street?

First of all, I think this campaign is very important and it is very exciting that it is happening because these are critical skills, especially today, where there is so much information coming from so many places: traditional media, the Internet and exploring the streets. It is very difficult to extract what is important, what is meaningful and what we are going to use to make decisions. Information literacy is a skill that in this current era ought to be promoted and I think it is very exciting that the S.U.R.E campaign is doing that today.

We need to Source, Understand, Research and Evaluate. These are all principles that scientists have also had to master in order to make sense of the complex objects that they study.

In scientific research, as in life, the information searching behaviour and processes are very similar. We should consider sources of our information, understand the data, research other avenues, obtain as many perspectives as we can and finally bring all of that information onto the table and try to make the best sense of it. And today as the world grows more and more complex, I think it is critical to improve our ability to deal with this growth of information that we encounter daily.

We are always concerned about whether the results of an experiment, which is the source of our information, are reliable. We need to understand what the context of that experiment is; what its strengths are and what its limitations are. Because we cannot see everything, our vision is always limited.

Scientific data is by its very nature a selective viewpoint and so to deal with this, we research other ways of looking into the same object and other experiments that will show other sides, other perspectives, other dimensions of the same problem. In order to see whether our perceptions match up, we need to evaluate the results. And this is the hardest part of experiments. To synthesise something, sometimes diverging results, contradictory findings, and make the best sense of our data.

I can speak about my own experience as a scientist, where basically we need to apply information literacy principles to our information searching behaviour and processes. We apply those same principles when we are looking at data and when we are looking at data from other laboratories. We always need to know where we are sourcing it from. We need to interpret the data and evaluate it. We need to place it in its broader context, understand what the biases are, and ultimately, try to make sense of it and synthesise all of these in our heads.

So, these are skills that translate back and forth between regular life on the street, life in the laboratory, life in the library and these are really critical skills that we need to develop. I think it’s very exciting that NLB has launched this initiative. And for me personally, also as a scientist, the approaches of S.U.R.E are important ways of making sense of an increasingly complicated world, both in life and science.

Would you say that the way that the brain processes information is similar to how we would apply the S.U.R.E. steps?

I would say that in some cases yes and some cases no. The brain takes shortcuts and the reason it takes shortcuts is because we cannot process everything. So, the nervous system, even at the very early levels – that of the purely sensory levels – is constantly filtering what is coming in and extracting the general shape of things without giving you all of the information. In some cases, this is very useful because this means we can react quickly to different situations, we can make decisions very quickly; but of course that leads us to errors sometimes.

With very few exceptions, the most elegant – and fruitful – neuroscience methods share a common principle: faced with the task of sorting out the daunting tangle of neurons and their incessant chattering, successful techniques tend to selectively restrict the vision of the scientist, rather than record everything under the sun. At any given moment we are aware of only a fraction of the details in our visual field: The brain excels at focusing on and extracting only the most meaningful signals flowing into the eye, providing us with only the information we need in order to react nimbly to events unfolding in the world around us.

And so, I would see something like what S.U.R.E. is doing as complementary because often the brain is right but sometimes it is wrong. When it goes wrong, it is when it fails to see different perspectives of the same things, fails to understand the sources and fails to understand biases of the information coming in. So I would say that by and large, the brain does a good job and then, every now and then, you really do need to go the extra step and fully analyse and source the situation that you are in.

Can you share with us more on how the brain functions – specifically how it controls our decision-making process?

We only know the very tip of the iceberg on this kind of problem and as I have already mentioned, neuroscience is still a very young field and we are just only going into these kinds of questions.

But it seems that decision-making happens at different levels: there are certain things that are purely instinctual, where you do not even think about what you are doing. Something comes in and you react to it automatically. For example, the simplest would be when you hear a loud bang and you immediately take cover or crouch. This is a decision – you are deciding to do that but you are not fully conscious of it.

And then there is an entire range of different levels of decision-making, things that can take anywhere from between 10 seconds to 10 hours and these are involving very different areas of the brain. And as it gets more and more complex, it is less and less understood. But what is clear is that all of these are happening at a physical level and we are beginning to see the correlation of these events.

Information relating to these kinds of decisions is encoded in the brain, essentially using electrical spikes of voltage. The basic idea is that all of these information, sensory and all that, ultimately gets represented physically and electrically in the brain. And as the brain filters all these information, there are different levels of decisions that can be made and there are very clear physical correlations of that as it is happening.

Conveniently, our brain automatically filters some information out, preventing confusion and helping you to solve the more pressing problem of saving your skin. Less information is far more useful, so long as it is good information. In one way or another, many of the most successful neuroscience techniques perform an analogous filtering. They enable the researcher to zero in on very specific features in nervous tissue, cutting out most of the overwhelming mess and preventing it from distracting you from focusing on the question you seek to answer. By imparting such a selective restriction of vision, the most ingenious methods have time and time again opened up formerly unsuspected universes.

The brain’s innate propensity to filter out information actually works to our advantage, cutting through the clutter of this age of information overload.

Currently an established neuroscience postdoctoral fellow in the Axel Laboratory at Columbia University, Dr Carl Schoonover is also the acclaimed author of Portraits of the Mind: Visualizing the Brain from Antiquity to the 21st Century (Abrams, November 2010), a book that chronicles the fascinating exploration of the brain through images. Watch his illuminating TED Presentation on this subject at: http://www.ted.com/talks/carl_schoonover_how_to_look_inside_the_brain.html

To view a full video of the exclusive interview with Dr Carl Schoonover, as well as highlights of S.U.R.E. Day, please visit: http://nlb.gov.sg/SURE