Standing Firm: Stories of Ubin

Apart from being an escape from the hubbub of city life, Pulau Ubin is home to a small but dwindling number of Singaporeans. Ang Seow Leng sheds some light on life on the island.

Sunset at Pulau Ubin jetty. Courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.com

Sunset at Pulau Ubin jetty. Courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.comOffshore islands such as Pulau Ubin have been largely spared the development that has taken place on mainland Singapore. However, recent land use plans have impacted Pulau Ubin’s landscape, its islanders and their rustic way of life.

Pulau Ubin is located northeast of Singapore, a mere 10-minute boat ride from Changi. The Malays once referred to the island as Pulau Batu Jubin, meaning “granite stone island”. At one time, the granite mined in Ubin was used to make floor tiles known as jubin, later shortened to ubin.1 The Chinese called the island chieo suar (石山), meaning “stone hill”.2 Originally, the 1,020-hectare island comprised a cluster of five smaller islands separated by tidal rivers, but over the years bunds erected for prawn farming unified the tiny isles into a single curved island that resembles a boomerang.3 Today, Pulau Ubin is Singapore’s second largest offshore island.4

Pulau Ubin was first visited by the Second Resident, John Crawfurd, on 4 August 1825 when he made his way around Singapore on his ship, the Malabar, to take formal possession of Singapore. The Union Jack was hoisted, followed by the firing of a 21-gun salute.5 Later, James Richardson Logan, who was responsible for the first scientific scholarly journal in Singapore – the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia – published a book on a study of the rocks and geological features of the island during his visit to Pulau Ubin in the early 19th century.

In the 1840s, Chinese stone cutters, and later convicts were deployed to quarry the granite in Pulau Ubin, which was later transported to Pedra Branca to build the Horsburgh Lighthouse in 1851.6 Granite from Pulau Ubin was also used to build the Raffles Lighthouse in 18557 and the Causeway in 1923.89 Pearl’s Hill Reservoir, Fort Canning, Fort Canning Reservoir, the expansion of Fort Fullerton and the Singapore Harbour were also built using granite from Ubin.10 A block of granite was even reportedly sent to build the extension of Portsmouth Cathedral in the south of England.11

The People of Ubin

The earliest inhabitants on Pulau Ubin were the Orang Laut and indigenous Malay of Bugis and Javanese origins. Subsequently, Chinese quarry workers settled on the island – mostly Hakkas, followed by the Hokkiens and later Teochews.12 In the 1880s, large numbers of inhabitants from the Kallang River area moved to Pulau Ubin. Migration spiked again prior to the Japanese invasion in 1942 when the mainland residents fled to Pulau Ubin for its perceived safety.13 Apart from quarrying granite, the main industry from the 1800s to 1999,14 other economic activities in the early days included rearing poultry and the cultivation of rubber and cash crops such as coffee, nutmeg, pineapple, coconut, durian and tobacco, as well as prawn farming and fishing.15

The 1970 Singapore population census indicated that there were 2,028 residents living on Pulau Ubin at the time.16 This number was halved by 1987 due to resettlement and the closure of the granite quarries. Even then, Ubin was the most populous island compared with Pulau Sakeng’s 250 residents, St John’s Island’s 10 residents and Kusu Island’s solitary temple keeper.17 By 2002, however, the number of residents on Ubin was down to just 100;18 today, fewer than 100 people live on the island.19 During a speech made on 15 March 2014, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong highlighted Pulau Ubin as one of the last two kampungs left in Singapore, the other being Kampong Buangkok.20

The rapid urbanisation of mainland Singapore has impacted Pulau Ubin in more ways than one. In the late 1960s and early 70s, Singapore embarked on a labour-intensive industrial programme, setting up factories and hiring as many workers as possible. At the same time, a public housing scheme was launched, which proved so effective that by 1985, some 80 percent of Singapore’s resident population was living in subsidised public flats.21 These flats on the mainland came with facilities that were sorely lacking in Pulau Ubin, such as piped water and electricity. Not surprisingly, Ubin’s more educated younger residents started moving to the mainland to seek jobs and a better life.

One prominent island resident was the late Lim Chye Joo, a Teochew migrant who was instrumental in the development of Pulau Ubin. He arrived in Singapore from China in 193622 and lived on Ubin all his life.23 Lim was the headman of the island for more than 30 years and was also the former chairman of the Pulau Ubin Community Centre. He helped set up Bin Kiang School on the island and was often involved in fund-raising activities,24 simultaneously rearing pigs and chickens, and running a provision shop. Until he was 90, Lim was still very active, walking at least 4 kilometres everyday to check on his vegetable and prawn farms.25 He passed away at the age of 101 in 2006.26

Housing, Land Use and Changes

Resettlement from Pulau Ubin to mainland Singapore began in the 1970s and picked up pace in the 1990s. The 1991 Concept Plan by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) proposed that while Pulau Ubin would be marked for leisure and recreation for as long as possible, once the population on the mainland exceeded 4 million, a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) and a major road would be constructed to link the mainland to Ubin. In addition, plans were unveiled for high density housing and industrial development on Ubin.27 Chek Jawa (at the southeastern tip) was also earmarked for land reclamation in 1992.

However, the proposed development did not take place and reclamation works on Chek Jawa were halted. In 1997, the URA proposed that Pulau Ubin would remain as a place for sports and recreation. Half of the land area would be set aside as a reserve site while a third of the land area would remain as open space. Two sites were proposed for the development of a holiday and outdoor recreation activity centre, in addition to the existing National Police Cadet Corps campsite and the Outward Bound School.28

An Island in Transition

The island has seen a sharp decline in population within just four generations, with many residents moving to the mainland in pursuit of better opportunities or to be with family. The closure of the last granite quarry in 1999 spelt the end of that means of livelihood for most of the islanders. Most jobs these days are geared towards meeting the needs of tourists who visit on the weekends. When provision shop owner Madam Tan was interviewed in 2000, she commented that there were five provision shops on the island vying for business from a small number of residents.29 In 2013, a resident observed that, “after a while, you see the same person pacing the town centre. It’s most likely the same villager you saw in the morning, rather than a fresh face from the mainland.”30

The island’s only primary school, Bin Kiang School, closed in 1985,31 the only clinic closed in 1987,32 and the Pulau Ubin Community Centre closed in 2003,33 all victims of the dwindling population. Places of worship, instrumental in binding the community together, have also moved to the mainland, leaving mostly the old and the retired behind. Furthermore, with the government acquiring the land in Pulau Ubin, residents now have to pay rent for the land they occupy. 34 One villager said, “Those who don’t live here think we have a relaxed time. Try it, and you’ll see how difficult it can be”; another shared that they had been surviving on the compensation given by the government after their fruit plantation had been acquired and were worried about how long they could survive without proper work.35

Making the move to the mainland has not been easy. A newspaper report in 2001 tells of Fadila Noor, aged 39, who packed up her belongings, left her cats behind, and moved into a one-room flat in Singapore, describing her flat as “barely larger than the kitchen in her house on the island”.36 Another, Madam Hamidah, shared that life in Ubin was “more peaceful, more calm… In Singapore, the moment you step out of your lift, you spend money. When you wake up and open your eyes, the first thing you think of is how to earn more money.”37

Communal Spaces in Pulau Ubin

There are some significant buildings in Pulau Ubin that bring people together and stand as markers of the island’s history. Bin Kiang School was the first and only primary school on the island. Set up in 1952, it had over 400 students at its peak until it closed in 1985 and was demolished in 2000.38

Pulau Ubin Community Centre was once a hive of activity and a key landmark on the island as Singapore’s only waterfront community centre. Built in 1961, the building was originally a community hall that was converted into a community centre in 1966.39 In the 1970s and 1980s, the centre offered residents a wide array of activities, from soccer and sepak takraw to dragon boat racing and traditional Malay sports such as miniature sailboats (jong) races and spinning tops (gasing) competitions.40 The community centre also followed the fate of the school, closing down in 2003.

In Chinese folklore, the Goddess of the Sea, or Mazu (妈祖), is an important celestial guardian who ensures the safe passage of fishermen and seafarers in rough seas. Worshipping Mazu is a practice that is mostly prevalent among Southeast Asian Chinese, and temples dedicated to Mazu are often situated along coastal areas. The Ma Zu Temple at Pulau Ubin was originally sea-facing but when the land it sat on was acquired to make way for the Outward Bound School Camp 2 site in 2001, the temple was moved to Sengkang on the mainland.41

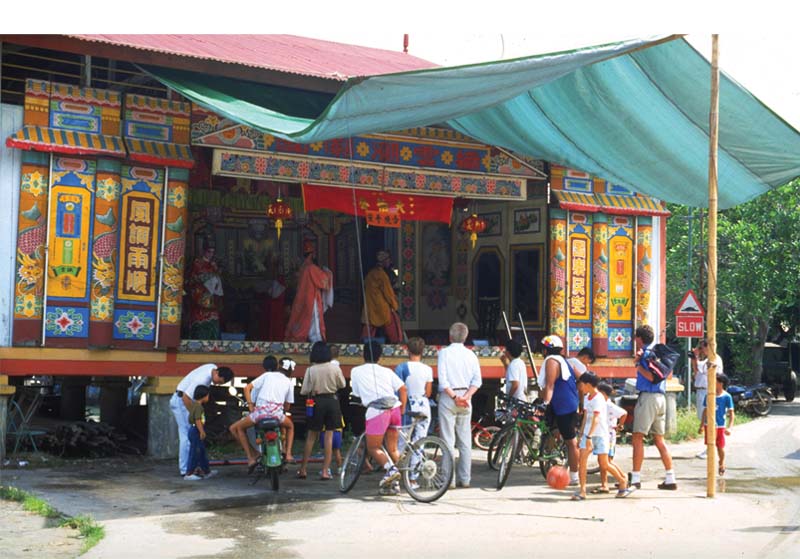

However, not all of Ubin’s buildings face closure or demolition. The Pulau Ubin Fo Shan Teng Tua Pek Kong Temple pre-dates 1869 according to the date inscribed on the temple’s renovation stele. The temple is located near the jetty and is one of the rare Chinese temples in Singapore that has a permanent stage for wayang (Chinese opera).42 The temple and its stage come alive twice a year, during the fourth and seventh months of the Chinese lunar calendar. Chinese operas and contemporary getai performances are staged in honour of Tua Pek Kong and to mark the Hungry Ghost Festival. This is a far cry from the 1950s when weekly wayang shows were put up to entertain the villagers.43

A crowd watching a Chinese opera performance on Pulau Ubin in 1992. The wayang (opera) stage still stands on the island. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A crowd watching a Chinese opera performance on Pulau Ubin in 1992. The wayang (opera) stage still stands on the island. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.House No.1, situated at the eastern end of the island near Chek Jawa, was built in the 1930s by the British Chief Surveyor, Landon Williams, as a holiday or weekend retreat.44 It is a significant landmark with commanding views of Changi Point and the Straits of Singapore. The structure is believed to be Singapore’s only remaining authentic Tudor-style house with a fireplace.45 A Lianhe Zaobao article reported that the building used to house the managers of the island’s rubber plantations.46 Rubber tapping activities ceased during the 1980s due to increasing costs of production.47 The house gradually fell into neglect but was given a new lease of life when it was restored and turned into the Chek Jawa visitor centre, and was given conservation status by the URA in 2007.48

People and places tell the story of the island, and unless there is a new “wave” of migration from the mainland, Pulau Ubin may become a fragment of a distant past that will slowly be replaced by new memories from transient visitors. In the meantime, there are plenty of enthusiasts in Singapore who try and keep Ubin alive and relevant. The island is thronged by mountain biking enthusiasts and nature buffs every weekend and the blog Pulau Ubin Stories was started in 1995 to collect news and stories about the island. In May 2014, a dedicated Facebook page provided another avenue for enthusiasts to share information and photos on Ubin.

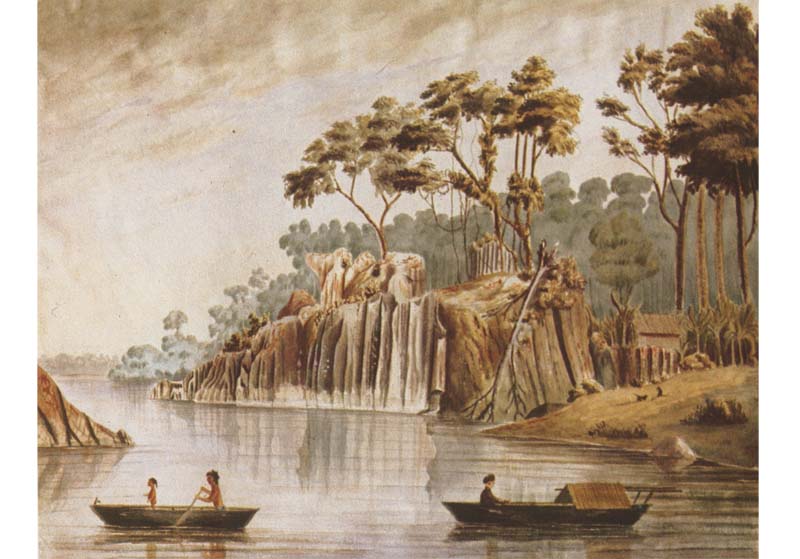

Author Dr Chua Ee Kiam located a similar rock that resembles the one captured in a striking painting done more than 150 years ago by John Turnbull Thomson – Grooved Stones at Pulo Ubin near Singapore. Hopefully, in spite of the island’s evolution and the encroachments made by man, that rock will still be around for another 100 years.

Painting of Pulau Ubin by John Turnbull Thomson. “Grooved stones on Pulo Ubin near Singapore, 1850”. Used with permission from the Hall-Jones family.

Painting of Pulau Ubin by John Turnbull Thomson. “Grooved stones on Pulo Ubin near Singapore, 1850”. Used with permission from the Hall-Jones family. Rock facade similar to that in the 1850 painting by John Turnbull Thomson, photographed by Dr Chua Ee Kiam. Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam.

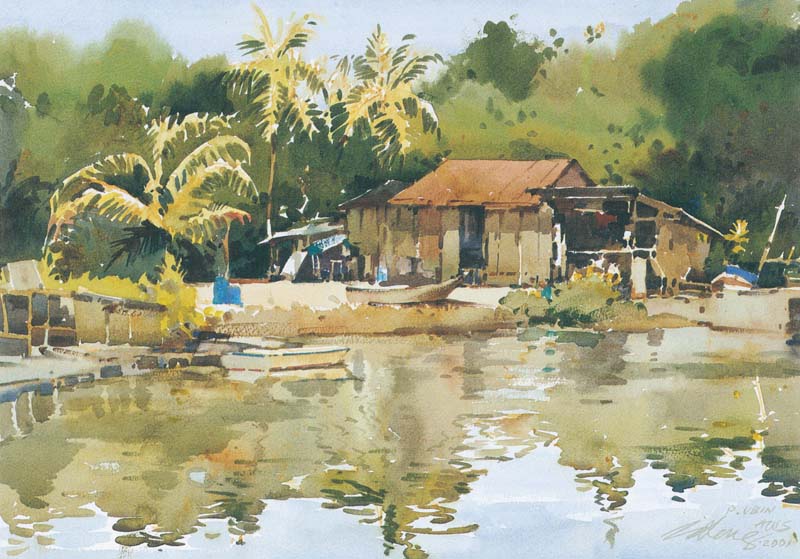

Rock facade similar to that in the 1850 painting by John Turnbull Thomson, photographed by Dr Chua Ee Kiam. Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam. Painting of prawn ponds on Ubin by Cultural Medallion winner Ong Kim Seng. Ong spent eight months painting on the island and his paintings were showcased in 2001 at “Charms of Ubin”, an exhibition held at the People’s Association headquarters, organised by the Outward Bound School to raise funds to develop an adventure park for children. Ong’s time on Ubin reminded him of his kampung days. Courtesy of Ong Kim Seng.

Painting of prawn ponds on Ubin by Cultural Medallion winner Ong Kim Seng. Ong spent eight months painting on the island and his paintings were showcased in 2001 at “Charms of Ubin”, an exhibition held at the People’s Association headquarters, organised by the Outward Bound School to raise funds to develop an adventure park for children. Ong’s time on Ubin reminded him of his kampung days. Courtesy of Ong Kim Seng.

UBIN’S FLORA AND FAUNA

In his book, Pulau Ubin: Ours to Treasure (2000), wildlife enthusiast Dr Chua Ee Kiam wrote about the natural areas in Pulau Ubin that were “a little wild, relatively undisturbed and support a large variety of indigenous flora and fauna”.49 He recorded a total of 179 species of birds, 382 species of vascular plants and 19 animal species on the island despite the fact that Ubin’s original rainforest was destroyed during the 1950s and early 1960s when entire hills were blasted for the extraction of granite.50 Ubin is still home to a relatively large number of rare animals, birds and plants. A National Parks Board (NParks) website on Ubin provides detailed records on the flora and fauna of the island.51 As of January 2014, the island is home to 603 species of plants, 207 species of birds, 153 species of butterflies and 39 species of reptiles.52

The oriental whip snake is also known as the green vine snake and can grow up to 2 metres long.

The oriental whip snake is also known as the green vine snake and can grow up to 2 metres long.

The nipah palm can be found in the mangrove swamps of Pulau Ubin. The leaves can be used as thatch for roofs and its sap, when fermented, is drunk as an alcoholic drink called “toddy”. Images courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.com

The nipah palm can be found in the mangrove swamps of Pulau Ubin. The leaves can be used as thatch for roofs and its sap, when fermented, is drunk as an alcoholic drink called “toddy”. Images courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.com

SAVING CHEK JAWA

Kampong Chek Jawa, on the southeastern tip of Pulau Ubin, was probably named after the Javanese who first settled there. The villagers who used to live there were mostly fishermen and rubber tappers.53 Chek Jawa has six different ecosystems within its 1 sq km area: mangroves, coastal hill forest, sandy ecosystems, rocky shore, seagrass lagoon and coral rubble.54 This rich diversity makes it a veritable haven for scientific studies and nature lovers.

In December 2000, Nature Society (Singapore) members made an accidental discovery of the rich marine life thriving at Chek Jawa.55 A newspaper article two years later reported that a biodiversity survey made at Pulau Ubin discovered several rare coastal plants, many of which were recorded for the first time in Singapore.56 News of Chek Jawa’s land reclamation and the imminent destruction of its ecosystem sparked off a deluge of visitors to the area. Numerous letters were sent to the press to appeal to the authorities to halt the land reclamation plans.57

On 14 January 2002, the Ministry of National Development announced that land reclamation work at Chek Jawa would be postponed indefinitely. In addition, NParks formed a committee with representatives from the Nature Society, Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research and other experts to study how Chek Jawa’s unique and fragile ecosystem could be maintained.58

High tide at the Chek Jawa boardwalk. Courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.com

High tide at the Chek Jawa boardwalk. Courtesy of Ria Tan, www.wildsingapore.com

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Reference Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing and developing content, as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

REFERENCES

Arumaintathan, P. (1973). Report on the census of population 1970, Singapore (Vol. 2). Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN)

Atoll’s history retold as myth. (2009, June 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

BoeKeng. (n.d.). Pulau Ubin Fo Shan Teng Tua Pek Kong Temple. Retrieved from Beokeng website.

Chandradas, G. (2001, July 8). Chek out this hidden Eden. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chua, E.K. (2000). Pulau Ubin: Ours to treasure. Singapore: Simply Green. (Call no.: RSING 333.78095957 CHU)

Chua, E.K. (2002). Chek Jawa: Discovering Singapore’s biodiversity. Singapore: Simply Green. (Call no.: RSING 333.91716 CHU)

Chua, E.K. (2001, July 28). Destruction of Chek Jawa will be a loss for all. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

D’Rozario, v. (2001, December 28). Chek Jawa an ideal outdoor classroom. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Geh, M. (2001, July 16). Chek Jawa’s natural beach should be preserved. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hall-Jones, J., & Hooi, C. (1979). An early surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore, 1841–1853. Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 526.90924 THO)

Helmi, Yusof. (2003, October 16). Farewell Ubin CC. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Heng, L., & Kang, A. (2013, April 13). This is our ONLY HOME. The New Paper, pp. 2–3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ho, B. (2005, April 27). He does it by… keeping life simple. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ho, M. (2001, November 4). The folks who live in paradise. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Leong, K.P. (2001, December 24). Chek Jawa has unique ecosystem. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lim, L. (2002, January 15). Reprieve for rustic Ubin. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Low, Y.L (1994, July). Isle be seeing you. Singapore Tatler.

Ministry of National Development. (2014, March 10). 2014 – Speech by MOS Desmond Lee “Working together to build a liveable and green Singapore” [Press release]. Singapore: Ministry of National Development. Retrieved from Ministry of National Development website.

Murphy, C. (2003, July 3). Destination Singapore – Pulau Ubin abode for Thai monk. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

National Heritage Board. (2013, March 14). Pulau Ubin. Singapore: National Heritage Board. Retrieved from Roots.sg website.

Chua, A. (2009). The Causeway. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Chew, V. (2009). Housing and Development Board. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Cornelius-Takahama, V. (2018, July). Raffles Lighthouse. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

National Parks Board. (2013, May 19). Pulau Ubin. Singapore: National Parks Board. Retrieved from National Parks Board website.

Neo, H.M. (2002, August 24). A kampong without village people. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Prime Minister’s Office Singapore. (2014, March 15). Transcript of speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at National Residents’ Committee Convention. Retrieved from Prime Minister’s Office Singapore website.

Pulau Ubin clinic to close from Tuesday. (1987, November 26). The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Pulau Ubin headman 101 dies. (2006, October 7). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Saifulbahri Ismail. (2013, April 17). Pulau Ubin residents to start paying rent for first year. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Singapore. Oral History Department. (1990). Recollections: People and places. Singapore: Oral History Dept. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 REC)

Stone from Malaya to help build English Cathedral. (1939, July 23). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, C. (1987, November 10). MPs take a boat ride to remote parts of their wards. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, H.Y. (1996, August 2). Take me to the headman’s house. The Straits Times, p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, T. (2000, December 4). Island living The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tay, S.C. (2007, October 6). Chek Jawa Visitor Centre. The Straits Times, p. 109. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (1991). Living the next lap: Towards a tropical city of excellence. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.36095957 LIV)

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (1997). Central water catchment, Lim Chu Kang, north-eastern islands, Tengah, western islands, western water catchment planning areas: Planning report 1997. Singapore: The Authority. (Call no.: RSING 711.4095957 SIN)

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (2007). Architectural Heritage Awards – No. 1 Pulau Ubin. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website.

Visitors’ centre for Chek Jawa? (2001, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

White, T. (2001, February 12). Leaving Ubin for life on mainland. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Zaccheus, M., & Ee, D. (2013, October 4). Pulau Ubin: Rustic or just rustling away? The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

叶孝忠 . (2001, July 14). 乌敏岛另类风情. 联合早报,第 35页 陈鸣鸾 (访员) (1987年11月4日) 林再有先生访谈文稿. National Archives of Singapore. Retrieved from http:// archivesonline.nas.sg/

NOTES

-

Atoll’s history retold as myth. (2009, June 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2013, March 14). Pulau Ubin. Singapore: National Heritage Board. Retrieved from Roots.sg website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2013, May 19). Pulau Ubin. Singapore: National Parks Board. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 14 Mar 2013. ↩

-

Hall-Jones, J., & Hooi, C. (1979). An early surveyor in Singapore: John Turnbull Thomson in Singapore, 1841–1853 (p. 96). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 526.90924 THO) ↩

-

Hall-Jones & Hooi, 1979, p. 103. ↩

-

Cornelius-Takahama, V. (2018, July). Raffles Lighthouse. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Chua, A. (2009). The Causeway. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Ministry of National Development. (2014, March 10). COS 2014 – Speech by MOS Desmond Lee “Working together to build a liveable and green Singapore” [Press release]. Singapore: Ministry of National Development. Retrieved from Ministry of National Development website ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 14 Mar 2013. ↩

-

Stone from Malaya to help build English Cathedral. (1939, July 23). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Oral History Department. (1990). Recollections: People and places (p. 60). Singapore: Oral History Dept. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 REC) ↩

-

Low, Y.L (1994, July). Isle be seeing you. Singapore Tatler, 78. ↩

-

Surana, S. (2014, January 5). Where the concrete hasn’t reached. The New York Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 14 Mar 2013. ↩

-

Arumaintathan, P. (1973). Report on the census of population 1970, Singapore (Vol. 2; p. 263). Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN) ↩

-

Tan, C. (1987, November 10). MPs take a boat ride to remote parts of their wards. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Neo, H.M. (2002, August 24). A kampong without village people. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of National Development, 10 Mar 2014. ↩

-

Prime Minister’s Office Singapore. (2014, March 15). Transcript of speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at National Residents’ Committee Convention. Retrieved from Prime Minister’s Office Singapore website. ↩

-

Chew, V. (2009). Housing and Development Board. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

陈鸣鸾 (访员)(1987年11月4日) 林再有先生访谈文稿. Retrieved March 27, 2014, from Archives Online. http://archivesonline.nas.sg/ ↩

-

Tan, H.Y. (1996, August 2). Take me to the headman’s house. The Straits Times, p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pulau Ubin headman 101 dies. (2006, October 7). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ho, B. (2005, April 27). He does it by… keeping life simple. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 7 Oct 2006, p. 2. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1991). Living the next lap: Towards a tropical city of excellence (p. 16). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.36095957 LIV) ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1997). Central water catchment, Lim Chu Kang, north-eastern islands, Tengah, western islands, western water catchment planning areas: Planning report 1997 (p. 14). Singapore: The Authority. (Call no.: RSING 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Tan, T. (2000, December 4). Island living. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M., & Ee, D. (2013, October 4). Pulau Ubin: Rustic or just rustling away? The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Murphy, C. (2003, July 3). Destination Singapore – Pulau Ubin abode for Thai monk. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Pulau Ubin clinic to close from Tuesday. (1987, November 26). The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Helmi Yusof. (2003, October 16). Farewell Ubin CC. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pulau Ubin residents to start paying rent for first year. (2013, April 17). Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Aug 2002, p. 8. ↩

-

White, T. (2001, February 12). Leaving Ubin for life on mainland. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Heng, L., & Kang, A. (2013, April 13). This is our ONLY HOME. The New Paper, pp. 2–3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Oct 2003, p. 2. ↩

-

叶孝忠 . (2001, July 14). 乌敏岛另类风情. 联合早报, 第 35页. ↩

-

BoeKeng. (n.d.). Pulau Ubin Fo Shan Teng Tua Pek Kong Temple. Retrieved from Boekeng website. ↩

-

Ho, M. (2001, November 4). The folks who live in paradise. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (2007). Architectural Heritage Awards – No. 1 Pulau Ubin. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Tay, S.C. (2007, October 6). Chek Jawa Visitor Centre. The Straits Times, p. 109. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Visitors’ centre for Chek Jawa? (2001, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore), 2007. ↩

-

Chua, E.K. (2000). Pulau Ubin: Ours to treasure (p. 13). Singapore: Simply Green. (Call no.: RSING 333.91716 CHU) ↩

-

The lists can be found in this National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Surana, 5 Jan 2014. ↩

-

Chua, E.K. (2002). Chek Jawa: Discovering Singapore’s biodiversity (p. 25). Singapore: Simply Green. (Call no.: RSING 333.91716 CHU) ↩

-

Chandradas, G. (2001, July 8). Chek out this hidden Eden. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Leong, K.P. (2001, December 24). Chek Jawa has unique ecosystem. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The letters included those written by prominent personalities in Nature Society. The Straits Times, 16 Jul 2001, p. 14; The Straits Times, 28 Jul 2001, p. 25; The Straits Times, 24 Dec 2001, p. 14; The Straits Times, 28 Dec 2001, p. 18. ↩

-

Lim, L, (2002, January 15). Reprieve for rustic Ubin. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩