The French Can: Pineapples, Sardines and the Gallic Connection

The Ayam brand of canned sardines was the brainchild of Frenchman Alfred Clouët. Timothy Pwee reveals its history and that of the pineapple canning industry in Singapore.

The French are linked to Singapore in many curious ways. Few people are aware that the French Revolution (1787–99) and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars (1803–15) were responsible for setting off the chain of events that not only led to Stamford Raffles founding an East India Company outpost in Singapore, but also the establishment of the canning industry on the island.

The introduction of tinned foods in Singapore is a French legacy that dates back to 1875, starting first with pineapples and then sardines. The pineapple industry has since shifted base to other Southeast Asian countries but one trademark, the Ayam brand of canned sardines, has endured over the years.

The history of the Ayam brand is intriguing because it was founded in Singapore around 1892. A. Clouët & Co (which was bought by the Denis Frères Company in 1954) is now an international business still based in Singapore with production centres in Asia and distribution centres the world over. The product range today includes canned sardines and tuna, baked beans, coconut milk and a variety of Asian sauces and condiments.

The Allure of Pineapples

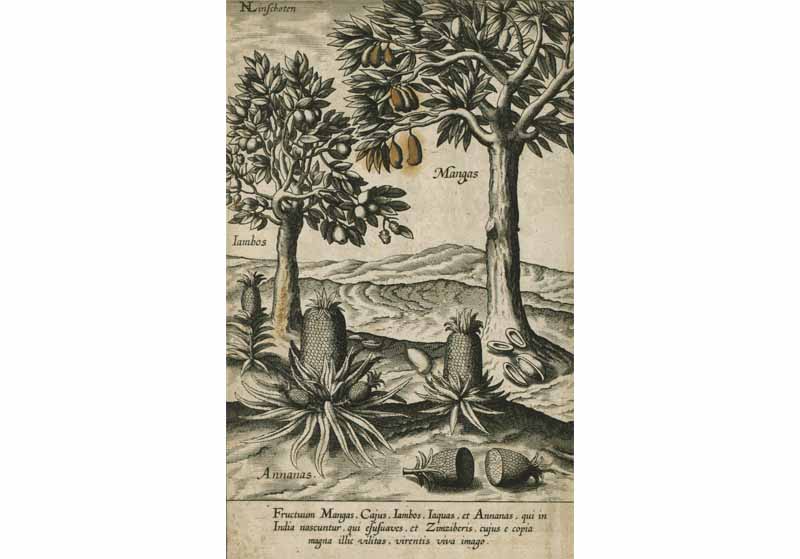

The plant species Ananas comosus, commonly known as the pineapple, is a fruit of the New World. It was discovered in Guadeloupe by Christopher Columbus on 4 November 14931 and brought back to Europe. The fruit proved popular and was transplanted by the Portuguese and Spanish in their explorations around the globe. Isaac Henry Burkill2 noted that the Portuguese learnt to call the pineapple “nana” from the Tupí natives of Brazil, and the word eventually evolved into “nanas” in the lands where the plant was introduced by the Portuguese. The Spanish, however, called it “piña” due to its resemblance to the pine cone, and the communities whom they introduced it to also used the Spanish name. The English name “pineapple” is in fact derived from the Spanish word “piña”. The Malays also call the pineapple “nanas”, while the Bugis refer to it as “pandang” because it resembles the fruit of the pandan plant (Pandanus amaryllifolius and related species).3

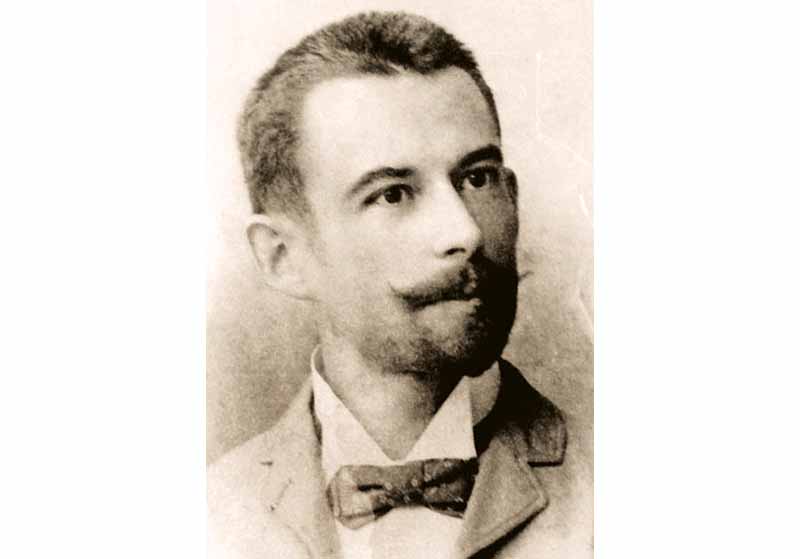

Alfred Clouët, the Frenchman who introduced the Ayam brand of canned sardines to Singapore in 1892. Courtesy of Denis Frères Company.

Alfred Clouët, the Frenchman who introduced the Ayam brand of canned sardines to Singapore in 1892. Courtesy of Denis Frères Company.

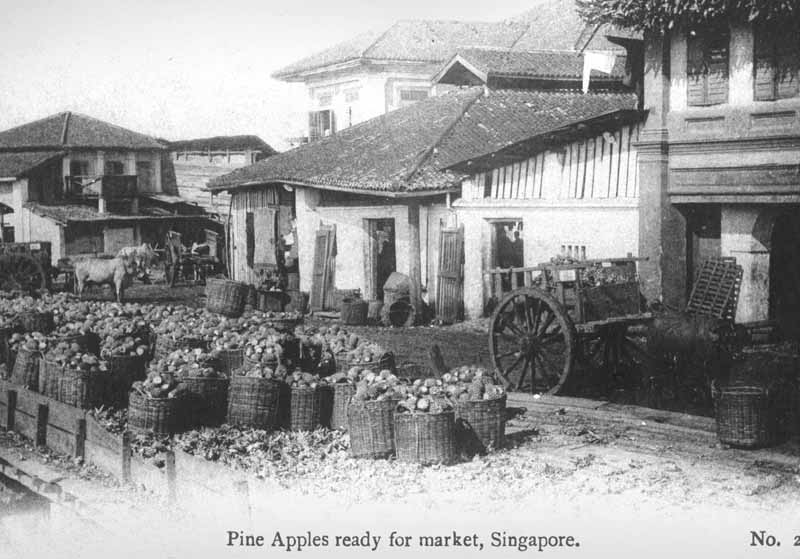

By the mid-1800s, the pineapple fruit was commonly available in Singapore. A pineapple market located by the Singapore River (likely in the Boat Quay area) had become a problem as early as 1844 when a letter in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser complained about the failure to remove “the Pine Apple Mart from the Riverside”.4 In 1848, a jury reporting to the court on Singapore’s affairs gave a very eloquent description of the market’s condition: “Indeed so great is the pineapple portion of the nuisance that the Jurors found one of the landing places so obstructed that to have descended the stairs would have been attended with the risk of a fractured Limb”.5 A letter written two years later called it a place where “obnoxious miasms are in constant process of manufacture”.6

Where did the pineapples come from? An 1861 article in The Straits Times describes pineapples that were sold for one cent each in Raffles Place: “Originally purchased from the Bugis planter at the rate of 16 for a cent, it was sold by the Chinese who bought it from the Bugis at the rate of 12 for a cent, sold again to the fruiter in the bazaar at the rate of six for a cent; it is now sold by the street hawker at 16 times more than its cost price”.7

In the mid-19th century, before the discoveries of Frenchman Louis Pasteur, diseases like malaria were thought to be caused by miasmatic vapours, or bad air, giving a more sinister tone to the 1850 letter of complaint about “obnoxious miasms”. This theory of miasmas had existed since the time of the ancient Greeks. In order to identify which miasmas were poisonous, a British doctor in Singapore, Robert Little Esquire, observed the population, their state of health and the surroundings. In 1848, Little reported his findings in Singapore’s first scholarly journal, The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, often referred to as Logan’s Journal after its editor James Richardson Logan.8 As Blákán Mátí (now known as Sentosa) was notorious for malarial fevers, Little and Logan surveyed Blákán Mátí and the surrounding islands. He described the hills on these islands as covered in pineapples, with Blákán Mátí having at least 200 acres of the fruit, mainly cultivated by the Bugis community.

Drawing of two pineapples from the 1598 book, John Hvighen van Linschoten, His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies: Devided into foure books. All Rights Reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2008.

Drawing of two pineapples from the 1598 book, John Hvighen van Linschoten, His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies: Devided into foure books. All Rights Reserved, National Library Board Singapore, 2008.

Pineapples ready for the market in Singapore, early 1900s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Pineapples ready for the market in Singapore, early 1900s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The First Attempts at Canning

The Singapore Directory for the Straits Settlements 1879 9 reports that a Frenchman named Laurent was the first in Singapore to produce preserved pineapples “some four years ago” (i.e. around 1875), but “his undertaking collapsed after a brief period.” Exactly why Laurent’s venture collapsed is unknown but financial difficulties are likely to have figured in his failure: an indignant letter published in 1877 by Victor Charles Valtriny, partner of C. Poisson & Co., complained against a court ruling favouring Laurent. The dispute was over money owed to Valtriny for a consignment of Laurent’s tinned pineapples that the former had shipped to Paris for sale.10 This Laurent is believed to be the same Jules Antoine Laurent who took over the Clarendon Hotel on Beach Road from the owner Charles Emmerson in 1874.11

It was another Frenchman who had some measure of success in the canning business. Joseph Pierre Bastiani was a seaman with French shipping company Messageries Maritimes, who arrived in Singapore in 1874.12 His 1925 obituary described him as a veteran of “the disasterous [sic] war… between France and Germany”, referring to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. Although Bastiani was not significant enough to be listed as a merchant in the 1879 Straits Settlements directory, there is, nonetheless, mention of Bastiani’s manufacture and export of canned pineapple “to the great marts of France and Italy”, calling it “an industry yet but in a partial state of development, but… one that may be looked forward as likely to provide a large amount of employment for the industrial and agricultural classes of the colony”.13

Besides Europe, Bastiani also looked to Australia as another market for his canned pineapples. The following year in 1880, Bastiani exhibited four products at the Melbourne International Exhibition:14 “preserved mangosteens, pine apples in own juice, pine apples preserved in syrup [and] pine apple syrup”.

In the 1881 edition of the Straits Settlements directory, Bastiani advertised himself as “Fruit Preserver, No, 8, 9, High Street, Singapore, and also at Sydney, Who was the first to introduce [about 7 years ago] the Manufacture of Preserves from Fruits grown in this Colony, obtained Medals at the Paris and Sydney Exhibitions for the excellence of quality, &c., of his goods”.15 The fact that he first called himself a pioneer in fruit preserves around 1875 strongly suggests that he may have been involved in the aforementioned Laurent’s venture. However, no evidence has been found to prove this.

Bastiani did not depend on just preserving fruit. In 1883, he started advertising his imported French products – cheeses, pâté, sardines, tomatoes, etc – in The Straits Times.16 By 1900, he had thought of returning home to Nice and apparently did so in 1902 when his residence and pineapple machinery at High Street were advertised for rent and sale respectively.17 At the time of his retirement, Singapore’s pineapple canning industry looked rosy, with demand outstripping supply. Bastiani’s cannery was then one of five major factories in Singapore – the others being Landau, Ghin Giap, Tan Twa Hee and Tan Lian Swee.

The logo of A. Clouët & Co Ltd bears the trademark cockerel, an unofficial symbol of France, 1892. Courtesy of Denis Frères Company.

The logo of A. Clouët & Co Ltd bears the trademark cockerel, an unofficial symbol of France, 1892. Courtesy of Denis Frères Company.

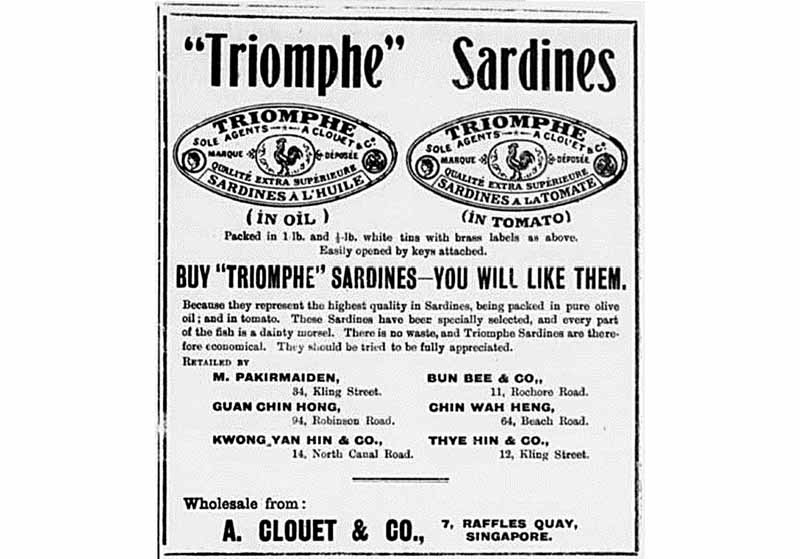

The combined Ayam-Triomphe brand of sardines was first advertised in The Straits Times on 23 March 1917 (p. 6). © The Straits Times.

The combined Ayam-Triomphe brand of sardines was first advertised in The Straits Times on 23 March 1917 (p. 6). © The Straits Times.

A 1915 US Department of Commerce report found that although pineapple production was concentrated in Singapore, it was planted as a catch crop18 by rubber plantations while waiting for rubber trees to mature. This meant that Singapore’s pineapple canneries did not have an assured supply of pineapple. Even so, Singapore was then still the leading exporter of canned pineapple in the world with 580,065 cases shipped in 1912. The bulk went to the United Kingdom (345,771 cases) and its colonies (105,141 cases). Included in the statistics is the output from Siam’s few pineapple factories; these were largely Singapore offshoots that sent their goods to Singapore for re-export.19

Why did Bastiani succeed where Laurent failed? It is of course only too easy to point to Laurent’s financial difficulties and his mounting debts. Like many other entrepreneurs, he was ambitious and experienced cash flow problems that swamped him. But there was one thing Bastiani did which Laurent failed to do: he exhibited his products at potential markets like Paris, Sydney and Melbourne, and even had an office in Sydney. This allowed him to make direct contact with the retailers in these foreign cities and take orders for his goods. Laurent on the other hand only sold his products to an agent in Singapore, who then exported them to Paris on consignment. This left Laurent dependent on a middleman who had no real stake in the success of his venture.

With Singapore’s expansion as a trading centre, agriculture and other low-value manufacturing was pushed out to the surrounding countries. A 2005 report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations stated that Thailand, Philippines and Indonesia account for “nearly 80 percent of the canned pineapple supply in the world market”.20

Alfred Clouët’s Ayam Brand

In 1892, Frenchman Alfred Clouët was already importing French wine (including Bordeaux and Claret), brandy and chocolates21 into Singapore. He also imported a French perfume that was branded with his trademark cockerel, which is an unofficial symbol of France. The cockerel belongs to the genus Gallus which in Latin means rooster as well as Gaul, the people of France. As Malay was the language of the marketplace at the time, the trademark became known as Chop Ayam (Chicken Brand).22 So while most Singaporeans think of the Ayam brand as being something very local, it is in reality a very foreign and colonial symbol.

Clouët’s fragrance “Ayer Wangi, Chop Ayam” (literally Ayam Brand Perfumed Water) had been selling for five years and became so well known that M. A. Gaffoor imitated Clouët’s packaging and adopted a similar trademark of two fighting cockerels (Chop Dua Ayam). Clouët was so incensed that he applied to the Supreme Court for an injunction against Gaffoor in February 1904 and won. Interestingly, Clouët published in The Straits Times a notice announcing his injunction against Gaffoor in October 1904 and had it reprinted again in April 1910.23 It seemed that he still had problems with Gaffoor six years later. The next case in December 1909 was against a Chiong Fye Wan for “applying a false trade mark to bottles of scent”. The scent bore a label with an image of a rooster, some English words and the words Messrs. Clouët & Co. in Malay. The accused was fined $25 and his goods confiscated.24

Like others in the trade, Clouët imported canned foods and sold them through retailers. His advertisement for French “Triomphe” canned sardines made its first appearance in the 15 March 1916 edition of The Straits Times and continued until 1918. However, along the way, the Chop Ayam trademark and the Clouët company name merged with the Triomphe name and appeared in the branding for the sardines. This combined branding first appeared in a 23 March 1917 advertisement.25 In December 1916, an advertisement offering 100 limited Christmas hampers for sale at $10 per hamper, each comprising 36 tins of “Ayam” Triomphe sardines, “Ayam” green peas and “Ayam” Alaska salmon was placed in The Straits Times. Interestingly, only the sardines carried the combined branding. It was only from 1934 onwards that sardines bearing solely the Ayam brand trademark were advertised.26

The Ayam brand represents the growth of one of Singapore’s first homegrown products in what is today known as the FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) sector. Although products sold under the Ayam brand were originally manufactured by others and brought in by Clouët, it was the brand name that became successful – a name painstakingly built up over the years. In 1922, an article in The Straits Times mentions that the A. Clouët & Co. stall in the local Malaya-Borneo exhibition and its “Ayam” brand had drawn many visitors.27 But the best testament to the strength of a brand is, ironically, the imitators it attracts and the consequent need of the brand owner to defend his trademark.

Although it has been claimed that Ayam brand sardines were canned in Singapore, there is no record of a fish cannery ever existing here or in the Malay Peninsula during the early 20th century. Although the colonial government’s Fisheries Department actively promoted the idea of a fish cannery in Malaya at the time, it never took off – but not from want of trying. In 1925, the director of fisheries complained, “No Malayan fish is tinned. Yet canned fish find a ready market even in Malayan fishing villages. Few sundry goods shops in such villages are without those large oval tins of large sardines imported from California. This canned fish is cheap even to the fisherman…” It was a decade later in 1936 that the Fisheries Department opened an experimental fish cannery in Kuantan – the first in Malaya.28 However, a cannery can only process fish when there is a ready and plentiful supply of fresh fish close at hand. According to Tom Burdon in his book, The Fishing Industry of Singapore, published by Donald Moore in 1955, canneries develop in association with fishing fleets but the waters around Malaya were not productive enough to support trawlers with the technology of that era.29

In 1954, the Denis Frères Company, run by the sons of a French mariner who settled in Saigon,30 bought the Clouët business from the son of one of Alfred Clouët’s partners, Ned Clumeck. They grew it into the firm you see today. Clouët Trading is now the dominant player in Singapore’s canned and preserved goods sector, holding 20 percent of the market share as at 2013.31 It is also a worldwide player under the name Ayam SARL, and one of 13 companies analysed by Research and Markets in their report for the global canned food market.32

CANNING AND THE FRENCH CONNECTION

The canning industry can be traced to the French Revolution of 1789–99 when France conscripted hundreds of thousands of men as soldiers. As it was impossible to feed that many men in the field – imagine the amount of fresh meat and vegetables to be sourced and transported daily – in 1795, a prize was put up by the Société d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale (Society for the Encouragement of National Industry) in Paris for anyone who could find a new and economical way to preserve food that was more nutritious than traditional salting, smoking and pickling.

Portrait of Nicolas Appert, inventor of food canning in 1795, tiré de Les Artisans illustres de Foucaud, anonymous woodcut, circa 1841. Les Artisans illustres 1841, collection Jean-Paul Barbier, Musée des Beaux Arts Châlons en Champagne. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Nicolas Appert, inventor of food canning in 1795, tiré de Les Artisans illustres de Foucaud, anonymous woodcut, circa 1841. Les Artisans illustres 1841, collection Jean-Paul Barbier, Musée des Beaux Arts Châlons en Champagne. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The man who claimed that prize 15 years later in January 1810 was Nicolas Appert, a chef who had set up a confectionery in Paris.33 Appert’s rudimentary method involved glass bottles sealed with cork and wire but the basic process he designed to seal food in containers and then heating the containers to kill bacteria and spores is still used today.

It was another patent registered in London by the British inventor Peter Durand that introduced the idea of using handmade wrought iron canisters, the precursor to the can as we know it. Intriguingly, Durand, who was of French origin, filed his patent in August 1810, just three months after Appert published the details of his process in Paris.34 This has led some to suggest that Durand stole Appert’s idea. However, retired Reading University food science lecturer Norman Cowell’s research has found evidence in a diary that names a Frenchman, Philippe de Girard, as having communicated the idea to Durand.35 That Girard’s name does not appear in the patent and only exists in an eyewitness account is not surprising given that Britain had been fighting with France since 1793, and hostilities would continue until Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815. Canning was an important advance in military logistics and it would have been ill-advised for a Frenchman like de Girard to openly advertise this transfer of technology to the British. Indeed, Durand later sold the patent to the British food company Donkin, Hall and Gamble who set up a canning factory and by 1812, the firm had begun to supply tinned food to the British army.36

Tin can used at the first canning factory in England, Bryan Donkin and Co., London, England, 1812. Bryan Donkin Archive Trust.

Tin can used at the first canning factory in England, Bryan Donkin and Co., London, England, 1812. Bryan Donkin Archive Trust.

Appert’s rudimentary method of preserving food using glass bottles sealed with cork and wire, collection Jean-Paul Barbier, Musée Châlons en Champagne salle Appert. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Appert’s rudimentary method of preserving food using glass bottles sealed with cork and wire, collection Jean-Paul Barbier, Musée Châlons en Champagne salle Appert. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Reference Librarian who handles the National Library’s Singapore collection. In a previous incarnation, he worked in a small business education outfit that gave him passing familiarity with the business world and the travails of small start-ups.

NOTES

-

Shephard, S. (2006). Pickled, potted and canned: The story of food preserving (pp. 221–227). London: Headline. (Call no.: 664.02809 SHE) ↩

-

Cowell, N.D. (2007, May). More light on the dawn of canning. Food Technology, 61 (5), 40–46. ↩

-

Shephard, 2006, p. 230; Busch, J. (1981). An introduction to the tin can. Historical Archaeology, 15 (1), 95–104. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Collins, J.L. (1949, October–December). History, taxonomy and culture of the pineapple. Economic Botany, 3 (4), 335–359. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Burkill, I.H. (1935). A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula (Vol. 1; p. 149). London: Governments of the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States. (Call no.: RCLOS 634.909595 BUR) ↩

-

A vocabulary of the English, Bugis, and Malay languages: Containing about 2000 words. (1833). Singapore: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 499.288.B8 VOC; Microfilm no.: NL5730); Burkill, 1935, vol. 1, p. 149. ↩

-

An Observer. (1844, December 5). Correspondence. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Purvis, J. (1848, May 13). Presentment. to the Hon’ble Her Majesty’s Court of Judicature of Prince of Wales Island, Singapore and Malacca. The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce, 2. ↩

-

Local. (1850, April 12). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled: Singapore by day and night, No. II. (1861, January 19). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Little, R. (1848, September). An essay on coral reefs as the cause of Blákán Mátí fever, and of the fevers in various parts of the East: Part II. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 2 (9), 571–602. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Keaughran, T.J. (1879). The Singapore directory for the Straits Settlements 1879 (p. 3). Singapore: Printed by Straits Times Off. Retrieved from BookSG. (Microfilm no.: NL1175) ↩

-

Valtriny, V.C. (1877, February 8). Commercial securities. The Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 3 Advertisements Column 3: Notice. (1874, March 28). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death of Mr. J. Bastiani. (1925, January 5). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An illustrated history (1819–today) (p. 86). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 305.84105957 PIL) ↩

-

Refers to a quick-growing crop grown between successive plantings of a main crop. ↩

-

Shriver, J.A. (1915). Pineapple-canning industry of the world (pp. 29–30). Washington: Department of Commerce. Retrieved from Archive Organisation website. ↩

-

J.de la C. M., & García, H.S. (2005, November 13). Pineapple: Post-harvest operations (p. 15). Retrieved from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations website. ↩

-

Page 3 Advertisements Column 4: A. Clouet. (1893, May 25). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pilon & Weiler, 2011, p. 88. ↩

-

Singapore trademark action. (1904, February 20). The Straits Times, p. 5; Page 8 Advertisements Column 3: Trade mark. (1904, October 10). The Straits Times, p. 8; Page 8 Advertisements Column 2: A. Clouet. (1910, April 15). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Scent for the Crown. (1909, December 23). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 6 Advertisements Column 2: “Triomphe” Sardines. (1917, March 23). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrievd from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 6 Advertisements Column 2: 100 Xmas hampers. (1916, December 6). The Straits Times, p. 6; Page 6 Advertisements Column 2: For those who want the best. (1934, January 24). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malaya-Borneo: Arts and crafts section of exhibition. (1922, April 5). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaprSG. ↩

-

Fisheries Department. (1925, May 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7; Untitled. (1936, October 10) The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Burdon, T.W. (1955). The fishing industry of Singapore (p. 23). Singapore: D. Moore. (RCLOS 639.2095957 BUR) ↩

-

Pilon & Weiler, 2011, p. 163. ↩

-

Euromonitor International Ltd. (2015, April 1). Euromonitor sector capsule: Canned/preserved food in Singapore. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

GlobeNewswire Inc. (2013, October 21). Canned food – A global market overview. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

From the Daily Times, 1st July: Melbourne International Exhibition 1880. (1880, July 3). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore and Straits Directory for 1881 (p. 6). (1881). Singapore: Printed by Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 382.09595 STR; Microfilm no.: NL1176) ↩

-

Page 5 Advertisements Column 3: Notice. (1883, January 9). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 3: Notice. (1900, June 9). The Straits Times, p. 2; Page 3 Advertisements Column 4: To be let. (1902, April 3). The Straits Times, p. 3; Page 3 Advertisements Column 3: Powell & Co. (1902, April 9). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩