Mohamed Eunos Abdullah: The Father of Malay Journalism

The Eunos area in the east of Singapore is named after the pioneer, Mohamed Eunos Abdullah. Mazelan Anuar traces his legacy.

Possibly the only extant image of Mohamed Eunos Abdullah. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Possibly the only extant image of Mohamed Eunos Abdullah. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

There is a popular Malay proverb that says: When a tiger dies, it leaves behind its stripes. When a man dies, he leaves behind his name.

Have you ever wondered about the origin of the name Eunos while travelling in the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) train between Kembangan and Paya Lebar stations along the East West line?

Heritage buffs may be interested to know that Jalan Eunos, Eunos Avenue, Eunos Crescent, Eunos Link, Eunos Road and Eunos Terrace are all named after the prominent Malay pioneer, Mohamed Eunos bin Abdullah.1

Regarded as the “Father of Malay journalism” by the community, Eunos Abdullah was the first Malay representative on the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements, and was also the co-founder and first president of Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (Singapore Malay Union), the first Malay political party in Singapore.

Not much is known about Eunos Abdullah’s early life. The popular narrative suggests that he was born to a well-to-do family in 1876. It cannot be ascertained if he was born in Singapore or Sumatra in Indonesia.2 In any case, his father was a wealthy Minangkabau merchant from Sumatra who could afford to send him to school in Singapore. Eunos Abdullah grew up in Kampong Glam and received his early education at a Malay school there. He then attended the elite Raffles Institution along Bras Basah Road, which had opened in 1837, where the medium of instruction was English. Schooled in both languages and effectively bilingual, this later served him well in his journalistic and political careers.

Eunos Abdullah completed his education between 1893 and 1894 and joined the office of the Master Attendant of Singapore Harbour. He was later appointed as harbour master at Muar by the Johor government. He held this appointment for five years before returning to Singapore.3

In 1907, Eunos Abdullah was invited to be the editor of the Utusan Melayu (Malay Herald), the Malay edition of the Singapore Free Press (the predecessor of The Straits Times) by its British owner, Walter Makepeace. Utusan Melayu was the only Malay newspaper in circulation at the time and it soon became Eunos Abdullah’s main vehicle to champion the Malay cause and to highlight pertinent issues important to the community. In 1914, he left Utusan Melayu to assume editorship of Lembaga Melayu (Malay Institution), the Malay edition of the newly launched English newspaper Malaya Tribune. Like Utusan Melayu, Lembaga Melayu became the voice of moderate, progressive Malay opinion.4

“Father of Malay Journalism”

Eunos Abdullah began his career in newspapers at a time when the prestigious Jawi Peranakkan, the first Malay newspaper in Singapore, ceased publication in 1896. Its successor, Chahaya Pulau Pinang, had also lapsed after a successful run from 1900 to 1906. Utusan Melayu became the first major national Malay newspaper to be circulated throughout the Straits Settlements and the Malay States. It was first published on 7 November 1907 with the objective of providing the Malay community with an intelligent and impartial view of the world’s news, as well as news and current affairs of Malaya.5 The paper’s strong didactic tone reflected Eunos Abdullah’s desire to reform the Malays and his concern for them to catch up with the other races. The newspaper was also used as a teaching tool in Malay vernacular schools.

When Eunos Abdullah was appointed editor of Lembaga Melayu in 1914, he did not sway from his goal of improving the socio-economic position of the Malay community. Lembaga Melayu’s policy and tone mirrored that of Utusan Melayu’s; it toed the official line, but could be openly critical when Malay interests were not addressed by the colonial government.

Through his editorials in both newspapers, Eunos Abdullah espoused nationalist ideals; he frequently discussed the idea of Malay bangsa (race), defined “Malayness” and Malay identity, invoked the concept of bumiputra (original “sons of the soil”) and hinted at the need for self-government.6 These ideals later became part of the Malay political vocabulary and influenced Malaya’s political development as it fought for independence after World War II.

The Malay press in Singapore flourished for a quarter of a century under the tutelage of Eunos Abdullah and as a testimony of his contributions, he has been aptly recognised as the “Father of Malay journalism”.7

Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (KMS)

Through his writings in the newspapers and service to the Mohamedhan Advisory Board – established in 1915 to advise the colonial government on Muslim religious matters and customs – Eunos Abdullah gained considerable influence within the Malay community.

As recognition of his exalted position among the Malays, Eunos Abdullah was first appointed as a justice of peace, and subsequently in 1922, became the first Malay to be appointed as a member of the Municipal Commission in Singapore – the governing body overseeing local urban affairs at the time. In 1924, the colonial government decided to increase the Asian representation in the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements, and appointed Eunos Abdullah as its first Malay legislative councillor.8

Initially, Eunos Abdullah tried to push for reforms to elevate the socio-economic position of the Malay community through the Persekutuan Islam Singapura (PIS) or Singapore Islamic Association. However, he and other like-minded educated Malay elites grew frustrated with the leaders of the non-Malay Muslims of PIS for their inability to elevate the socio-economic conditions of the Malays. In 1921, they formed the breakaway Muslim Institute to compete with the PIS.

When the British government appointed Eunos Abdullah as its first Malay legislative councillor in 1924 instead of a representative from the PIS, his supporters realised that strong organisational support was required to bolster Eunos Abdullah’s position and that the Muslim Institute was inadequate in meeting this need.

Against this backdrop, the Singapore Malay Union, or Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (KMS), emerged in 1926 in a contest between an older Muslim elite of Arab and Indian descent and a newer emerging group of Malay elites. Apart from Eunos Abdullah, these English-educated Malay elites included Abdul Samad, the first Malay doctor, and Tengku Kadir, a lineal descendant of Sultan Ali of Johor. They were critical of the PIS – which were dominated by Muslims of Arab descent – for being elitist and called it “a rich man’s club”.9

The KMS was in effect the first quasi-political Malay organisation in Singapore, and Eunos Abdullah served as its first president. The organisation established Kampong Melayu in the eastern part of Sinapore, a Malay settlement that was later renamed Kampong Eunos. More importantly, the KMS was a forerunner of the various Malay political parties that later emerged in the post-war period, including the now dominant United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in Malaysia.10

Formally established on 14 May 1926 at Istana Kampong Glam, Eunos Abdullah became the first president of the KMS. Its objectives were: to encourage its members to play a greater role in public and government affairs; to sponsor Malay progress and interest in politics and education; to represent the Malay community in all matters concerning the rights and freedom of the Malays; and to foster higher and technical education for Malay children.11

Members of the KMS were mostly made up of English-educated Malay journalists, government officials, merchants, and people of traditional, secular and religious standing who advocated and strived for the socio-economic progress of the Malays. They recognised the importance of education and, through Eunos Abdullah in the Legislative Council, were successful in lobbying for the opening of a trade school for Malays in 1929.12

The birth of KMS marked a turning point in the political attitudes of the Malays. It signalled the beginning of efforts by the community to actively promote their rights and interests. Soon, other Malay unions modelled on the KMS were established in other parts of Malaya, with the similar expressed aim of representing Malay socio-economic and political interests.

As the community’s attention shifted from self-help to self-governance, Malay political organisations, including the KMS, evolved into political parties. However, the KMS did not push for independence during its initial years. In fact, it pledged to obey the laws of the colony and, in return, received support from the colonial government. Its earliest success of establishing Kampong Melayu was achieved with a government grant of $700,000.

Kampong Melayu

Inspired by the Malay settlement of Kampung Bahru in Kuala Lumpur, the KMS put up a proposal to the colonial government to set aside land for exclusive and undisturbed use as a Malay kampong (“village” in Malay).

Public opinion among the Malay community and various Malay clubs and societies towards the proposal was favourable.13 In early 1927, Eunos Abdullah, as president of the KMS and Malay member of the Legislative Council, lobbied successfully for government support. With the grant received, a 240-hectare plot of land was acquired in 1928 in the eastern part of Singapore. The site was given the name Kampong Melayu, and was later renamed Kampong Eunos.

The Kampong Melayu Malay Settlement faced many teething problems in its fledgling years. The residents of the settlement had to clear the land themselves in order to construct their new homes. The high land rental rates coupled with the high construction costs of houses deterred many eligible Malays from applying for allotments in Kampong Melayu. By 1931, only 50 to 60 houses had been built and occupied.14

In 1933, then chairman of the Rural Board W. S. Ebden commented that the Malay settlement was a failure because its inland location was inconvenient for Malays whose livelihoods depended on fishing and required easy access to the sea. The settlement’s remote location away from bus centres also posed problems for its residents.15

The Malay leaders closely associated with the Malay settlement project rejected Ebden’s view, but appealed to the government to reduce land rent so that more Malays could afford to move to Kampong Melayu. The development of the Malay settlement intensified when the residents from Kallang village were resettled there in order to make way for the construction of Kallang Airport. In 1960, the Malay settlement was extended to include the Kaki Bukit area. The register of settlers was closed in 1965 when it had some 1,300 houses.16

Eunos Abdullah and his peers believed that an authentic Malay life was best experienced in an exclusively Malay community. Kampong Melayu was imagined as a privileged site of a yet to be fulfilled “Malay nation” (bangsa Melayu), the material expression of KMS’ vision of the Malay bangsa and creation of a Malay identity. Only applicants who could demonstrate their “Malayness” were given temporary occupation licences for house plots in the settlement. Among other criteria, applicants had to be male, of Malay parentage, habitually spoke the Malay language, professed the Muslim religion and conformed to Malay customs. Provision of its own mosques, schools, a youth club and a village cooperative ensured that Kampong Melayu was self-sufficient.17 This ideal as envisioned by Eunos Abdullah remained until the Malay settlement was de-gazetted in 1981 to make way for the construction of the Pan Island Expressway.

Following his retirement in 1931 Eunos Abdullah suffered from poor health and passed away at the age of 57 on 12 December 1933 at his home on Desker Road. His body was laid to rest at Bidadari Cemetery.18

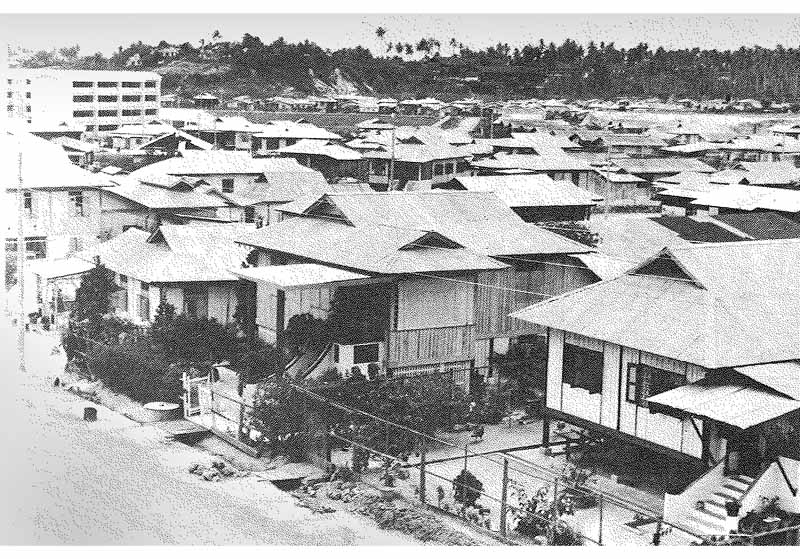

Bungalow-type dwellings made of wood and zinc in Kampong Melayu. All rights reserved, Singapore Ministry of Culture. (1963). Democratic socialism in action, June 1959 to April 1963 (p. 21). Singapore: Ministry of Culture.

Bungalow-type dwellings made of wood and zinc in Kampong Melayu. All rights reserved, Singapore Ministry of Culture. (1963). Democratic socialism in action, June 1959 to April 1963 (p. 21). Singapore: Ministry of Culture.

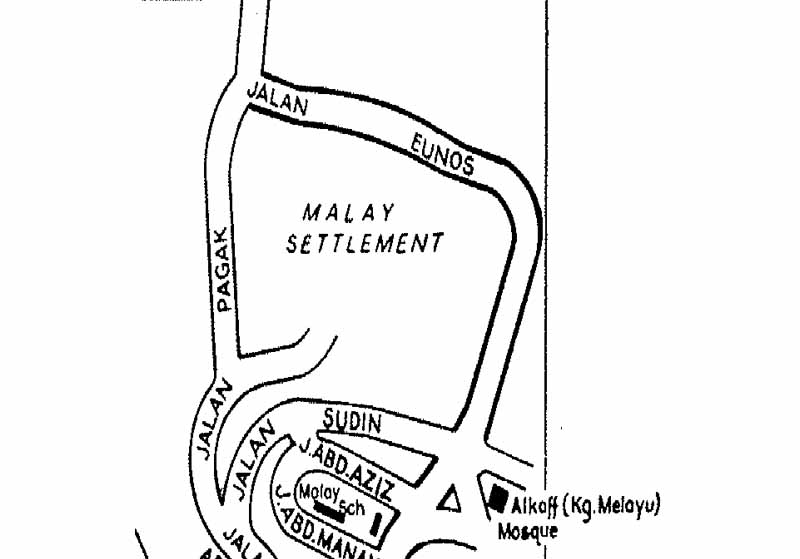

1956 street directory indicating the location of Jalan Eunos and the Malay Settlement. All rights reserved, Singapore Survey Department. (1950–75). Singapore street directory and sectional maps (Map no. 60). Singapore: Survey Department.

1956 street directory indicating the location of Jalan Eunos and the Malay Settlement. All rights reserved, Singapore Survey Department. (1950–75). Singapore street directory and sectional maps (Map no. 60). Singapore: Survey Department.

RISE AND FALL OF UTUSAN MELAYU

Utusan Melayu, which Eunos Abdullah edited, was initially published three times a week on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. It was converted into a daily in 1915 to meet the demand for news of World War I. In 1921, the newspaper was sued by Raja Shariman and Che Tak, assistant commissioners of police of the Federated Malay States, for damages over an alleged libel. At the time of the libel, the newspaper’s circulation had dipped below 280 copies.19 The heavy damages awarded against Utusan Melayu turned out to be financially crippling and it ceased operations as a result.

Perhaps as a tribute to Eunos Abdullah, his successor, Ambo Sooloh, along with other Kesatuan Melayu Singapura leaders and members such as Yusof Ishak (later the first president of Singapore) and Abdul Rahim Kajai, started another newspaper in 1939. They called it Utusan Melayu but unlike the first version of Utusan Melayu, this reincarnation was fully owned, financed and managed by Malays.20 In 1958, the newspaper relocated its operations to Kuala Lumpur.

KMS AND THE UMNO CONNECTION

After World War II, the Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (KMS), together with more than 40 other Malay unions from different Malay states, presented a united front to protest against the Malayan Union proposal by the British to reduce the status and role of Malay kings and leaders, and to separate Singapore from Malaya. The Malayan Union was eventually replaced by the Federation of Malaya in 1948.21 Under the leadership of Dato’ Onn Ja’afar, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) had emerged as the leading political party in Malaya. In 1953, KMS merged with UMNO to form the Singapore branch of UMNO. Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the Singapore branch was officially renamed Pertubuhan Kebangsaan Melayu Singapura (PKMS) in 1967 to comply with government regulations that prohibited local parties from affiliating with foreign organisations.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He has been involved in exhibition projects such as “Aksara: The Passage of Malay Scripts” and “Rihlah: Arabs in Southeast Asia”, and is part of the library’s NewspaperSG team, an online archive of Singapore newspapers dating back to 1831.

REFERENCES

Adlina Maulod. (2010). Mohamed Eunos bin Abdullah. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Chia, Y.J., & Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman. (2016). Utusan Melayu. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Cornelius-Takaham, V. (2016). Jalan Eunos. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore.

Death of Inche Eunos bin Abdullah. (1933, December 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y. (2009). Singapore: A biography. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO)

Inche Eunos. (1933, December 14). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kahn, J.S. (2006). Other Malays: Nationalism and cosmopolitanism in the modern Malay world. Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Singapore University Press and NIAS Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76209595 KAH)

Kesatuan Melayu Singapura. (1999). Ensiklopedia sejarah dan kebudayaan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia. (Call no.: Malay R 959.003 ENS)

Matters of Muslim interest. (1931, September 22). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Milner, A.C. (2002). The invention of politics in colonial Malaya. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5 MIL)

National Archives (Singapore). (1986). Geylang Serai: Down memory lane: Kenangan abadi. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 779.995957 GEY)

National Library Board. (2014). Singapore Malay Union is formed. Retrieved from HistorySG website.

National Library Board. (2014). First issue of Utusan Malayu (1907–1921) is published. Retrieved from HistorySG website.

National Library Board. (2015, March). Mohd Eunos bin Abdullah is appointed Municipal Commissioner. Retrieved from HistorySG website.

Roff, W.R. (1994). The origins of Malay nationalism. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 320.54 ROF)

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Settlement a failure. (1933, May 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, H.Y. (1997, September 12). Eunos upgrading programme gets a marine flavour. The Straits Times, p. 55. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819–1988. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR)

Utusan Malayu. (1907, November 9). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (p. 120). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV) ↩

-

Adlina Maulod. (2010). Mohamed Eunos bin Abdullah. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Death of Inche Eunos bin Abdullah. (1933, December 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Roff, W.R. (1994). The origins of Malay nationalism (pp. 159, 161). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 320.54 ROF) ↩

-

Utusan Malayu. (1907, November 9). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Milner, A.C. (2002). The invention of politics in colonial Malaya (pp. 98–107). New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5 MIL); Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y. (2009). Singapore: A biography (pp. 195–198). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2015, March). Mohd Eunos bin Abdullah is appointed Municipal Commissioner. Retrieved from HistorySG website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014). Singapore Malay Union is formed. Retrieved from HistorySG website. ↩

-

Matters of Muslim interest. (1931, September 22). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Settlement a failure. (1933, May 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cornelius-Takaham, V. (2016). Jalan Eunos. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Kahn, J.S. (2006). Other Malays: Nationalism and cosmopolitanism in the modern Malay world (pp. 10–14). Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Singapore University Press and NIAS Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76209595 KAH) ↩

-

Inche Eunos. (1933, December 14). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014). First issue of Utusan Malayu (1907–1921) is published. Retrieved from HistorySG website. ↩

-

Chia, Y.J., & Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman. (2016). Utusan Melayu. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore. ↩

-

Kesatuan Melayu Singapura. (1999). Ensiklopedia sejarah dan kebudayaan Melayu (p. 1186). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia. (Call no.: Malay R 959.003 ENS) ↩