A Chinese Classic in Baba Malay

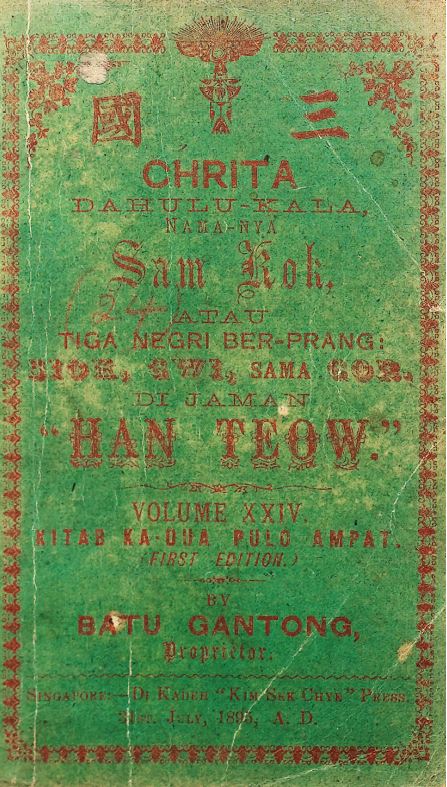

Title: Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam

Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok,

Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow”

(Ancient Story Entitled Sanguo or the Three

Kingdoms at War: Shu, Wei and Wu During

the Han Dynasty)

Author: Chan Kim Boon (1851–1920)

Year published: 1892–1896

Publisher: Kim Sek Chye Press (Singapore)

Language: Baba Malay

Type: Book (30 volumes); 4,622 pages in

total

Location: Call no.: RRARE 895.135 CHR

Accession no.: B00607851E (v.24)

Donated by: National Museum Singapore

Written in the 14th century and set during the last days of China’s Han dynasty and the tumultuous Three Kingdoms period (circa AD 220–280), the Romance of the Three Kingdoms is a well-known Chinese classic of epic proportions and a cast of thousands. In the late 1800s, a Baba Malay version of this classic was published in Singapore – making this popular tale more accessible to the Peranakan (Straits-born Chinese) community.1

Titled as Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow” (henceforth referred to as Sam Kok), the series consists of 30 volumes translated from Chinese to Baba Malay. The translation was done by Chan Kim Boon, an administrator at law firm Aitken & Rodyk,2 with the help of two other people, Chia Ann Siang and Tan Kheam Hock.3

Published between 1892 and 1896 by Kim Sek Chye Press, the entire series totalled some 4,622 pages, and a single volume was sold at a $1 each.4 Sam Kok is most likely the earliest complete Malay translation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms, ahead of Indonesian versions from Java published in 1910.5 The series was typical of Baba Malay materials in Malaya at the time, where epic stories were serialised into multi-volume publications. This facilitated a subscription-based model that spurred the growth of the fledgling Baba publishing industry in Singapore.6

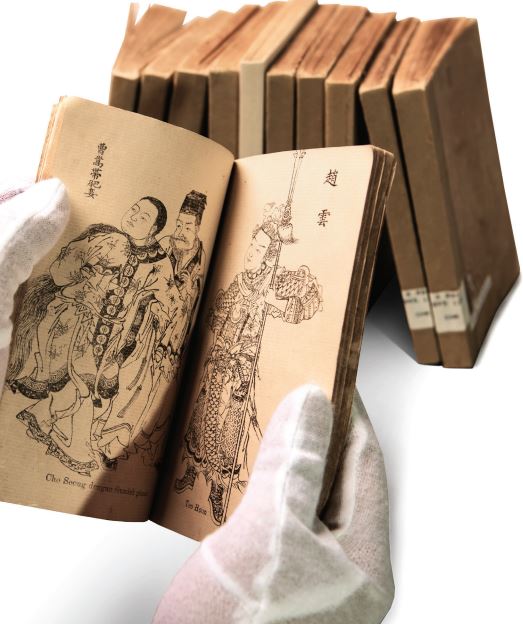

The majority of the translated Baba Malay literary works were heavily illustrated to complement the storyline and heighten the visual appeal of the publications. These drawings, rendered in the style of traditional Chinese woodcuts, usually featured main characters and events in the stories.7

Interestingly, Chan encouraged communication between himself and the readers and even among readers themselves by publishing letters in English, Chinese and Malay containing comments on previous volumes of the book. He also shared his trials and tribulations in producing the books as well as his financial woes, photographs of himself and his assistants and other private information.8

Such translations of Chinese historical novels into Baba Malay first took place in the 1880s in Batavia (now Jakarta). They were well-received by the Peranakan community there and soon made their way to Singapore.9 The earliest translations in Singapore were undertaken by businessman Tan Beng Teck, who left for Japan and discontinued his translation works. Chan then took over, and even revised Tan’s earlier works.10

Chan became a dominant influence in the small Baba Malay publishing industry, gaining prominence for his translation of three popular Chinese classics: apart from Sam Kok, he also translated two other Chinese classics, Song Kang (Water Margin) and Kou Chey Tian (Journey to the West).11 After his death in 1920, the translation of Chinese stories into Baba Malay declined,12 due in part to the Peranakan community’s increasing preference for English-language books.13

The son of a Penang trader, Chan was educated in English at the Penang Free School, and received private tuition in Chinese. He arrived in Singapore in March 1872, and built a career as an administrator at Aitken & Rodyk. The book-keeper and cashier, however, became better known for his translations of Chinese classics into Baba Malay, which he diligently worked on after office hours.14

It was Chan’s publication of Sam Kok that brought him fame, primarily because it was a massive work that was serialised over 30 volumes. The series also included Chan’s footnotes, which provided details of Chinese culture as well as notes on romanised Malay terms and names, to which Chinese text was added for clarification. Jokes and even a portrait of the author were included in the series.15

Chan was known by the pen-name Batu Gantong (literally “Hanging Rock”), which is the name of a cemetery in Penang. Some people believed that this was an allusion to his preference for his final resting place. Chan’s home at 75 Lebuh Muntri in Georgetown, Penang, has today become a tourist destination because of the fame that Chan had gained through his Baba Malay translations.16

– Written by Mazelan Anuar

NOTES

-

The term Peranakan generally refers to people of mixed Chinese and Malay/Indonesian heritage. Peranakan males are known as babas while the females are known as nonyas (or nyonyas). See National Library Board. (August 26, 2013). Peranakan (Straits Chinese) community written by Koh, Jaime. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). Chan Kim Boon written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Yoong, S. K., & Zainab, A. N. (2002, December). Chinese literary works translated into Baba Malay: A bibliometric study. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 7 (2), 21. Retrieved from University of Malaya website. ↩

-

Yoong & Zainab, Dec 2002, p. 21. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (pp. 25–26). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO-[LIB]. ↩

-

Proudfoot, 1993, p. 24; Yoong, S. K., & Zainab, A. N. (2004, December). The Straits Chinese contribution to Malaysian literary heritage: Focus on Chinese stories translated into Baba Malay. Journal of Educational Media & Library Sciences, 42 (2), 195. Retrieved from e-lis website. ↩

-

Yoong & Zainab, Dec 2004, p. 184; Salmon, C. (Ed.). (2013). Literary migrations: Traditional Chinese fiction in Asia (17th–20th centuries). Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. Cal no.: RSING 895.134809 LIT. ↩

-

Yoong & Zainab, Dec 2002, p. 7. ↩

-

Yoong & Zainab, Dec 2004, p. 186. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008; Discovering the streets of George Town. (n. d.). Retrieved from Vintage Malaya website. ↩