Crawfurd on Southeast Asia

Title: A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries

Author: John Crawfurd (1783–1868)

Year published: 1856

Publisher: Bradbury & Evans (London)

Language: English

Type: Book; 459 pages

Call nos.: RRARE/RDYTS 959.8 CR

Accession nos.: B03013481I; B02966867K

Copies donated by: Mrs Loke Yew and Tan Yeok Seong

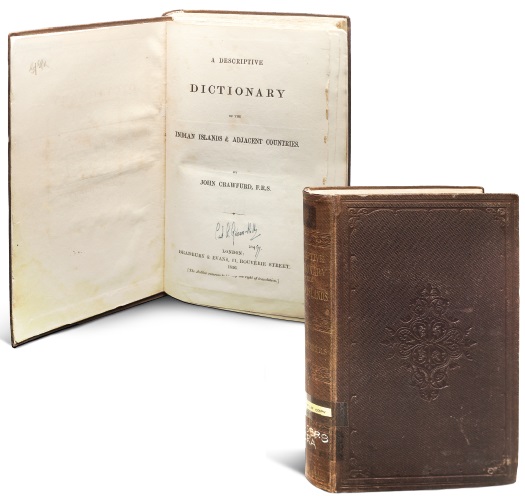

The title page of A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries bears the signature of Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, a noted scholar and naturalist as well as the last British director of the Raffles Museum. This copy was donated to the National Library in June 1956 as part of the Gibson-Hill Collection by Mrs Loke Yew on behalf of her late son, Loke Wan Tho, first chairman of the National Library Board. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The title page of A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries bears the signature of Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, a noted scholar and naturalist as well as the last British director of the Raffles Museum. This copy was donated to the National Library in June 1956 as part of the Gibson-Hill Collection by Mrs Loke Yew on behalf of her late son, Loke Wan Tho, first chairman of the National Library Board. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.British colonial administrator John Crawfurd once wrote that the Chinese in 19th-century Southeast Asia have a “propensity to form secret societies [that] has sometimes proved inconvenient”. But on the whole “they are peaceable subjects”, he added, and in the event of a foreign invasion, “their cooperation might certainly be relied on by a British government”.1

This and other nuggets of information about colonial Southeast Asia are recorded in A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries, Crawfurd’s last scholarly publication before his death in 1868. Crawfurd, who was first posted to Penang in 1808 and served as Singapore’s second British Resident from 1823 to 1826, was one of a small school of colonial officials who industriously studied the local languages and cultures of the areas they governed and then published their observations.

Their efforts provided the earliest reliable documentations of the region, laying the foundation for modern Southeast Asian studies. During Crawfurd’s 20 years of service in the Far East, he made careful notes of the places he visited: India, Penang, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and Burma. These findings were published in books such as History of the Indian Archipelago (1820) and Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China (1828) – classic texts that historians still refer to today.

Crawfurd originally envisioned A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries as a second edition of History of the Indian Archipelago, his definitive work on the East Indies. However, he decided to rewrite material from History and add new content, using an alphabetical format that would facilitate easy referencing on this vast subject. The keyword index he used in A Descriptive Dictionary proved particularly useful for readers, grouping information under broad headings like “language”, “arms”, “dress” and “weights and measures”. While the book’s focus is on Java, where Crawfurd spent five years, it also offers rich information on the Malay Peninsula, the Philippines and mainland Southeast Asia – areas Crawfurd had become familiar with through his diplomatic missions and intellectual inquiry.

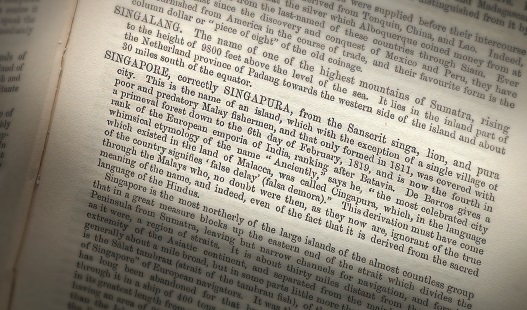

The dictionary’s entry on Singapore, for instance, spans eight pages and covers the origin of the island’s name, as well as its geological formation, climate, plants, zoology, agriculture, industry, trade, population, government, revenue and history. As one of the earliest accounts of Singapore, it set a model for later writers and provided a helpful reference for terms related to 19th-century Singapore, such as Bugis (under the entry on People), sago (Production), opium (Trade), kati (Weights and Measures) and pantun (Literature).

The entry on Singapore is found on pages 395 to 403 of the book. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The entry on Singapore is found on pages 395 to 403 of the book. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.In the introduction of the 1971 reprint, eminent historian of Indonesia Merle C. Ricklefs praised the volume for its enduring value well over a century after it was first printed. He described it as “a mine of statistical and descriptive information, made available in a readily accessible form which was unusual for its time”. Although Southeast Asia had changed greatly in the interim, “the volume is of interest not only as an illustration of how much has changed, but perhaps also of how much still remains the same”, he added.2

One caveat is that the A Descriptive Dictionary is largely based on Crawfurd’s personal observations, which were not always objective, as Ricklefs has noted. Among other things, Crawfurd describes opium as a harmless stimulant,3 dismisses Javanese literature as “inferior to the literature of the Hindus”,4 and assesses Stamford Raffles as “an original thinker, but [one who] readily adopted the notions of others – not always with adequate discrimination”.5

Still, the book’s extensive facts and figures reflect Crawfurd’s wide scholarly interests. Its inclusion of information dated as late as 1850 also hints at his dedication to Southeast Asia even after he returned to England for good in 1828. Crawfurd, who was born in Scotland in 1783 and started working for the British East India Company at the age of 20, began work on A Descriptive Dictionary in 18546 and published it in London in 1856. The book served as the standard reference on the Indian Archipelago for almost 40 years until Nicholas Belfield Dennys’ Descriptive Dictionary of British Malaysia was published in 1894.7

The National Library holds four copies of the first edition published in 1856. One is from the Ya Yin Kwan Collection, donated in July 1964 by Penang-born merchant and scholar Tan Yeok Seong. Another copy was donated in June 1965 as part of the Gibson-Hill Collection by Mrs Loke Yew on behalf of her late son Loke Wan Tho, the first chairman of the National Library Board and the owner of the Cathay chain of cinemas. The third copy comes from the John Bastin Collection.

– Written by Gracie Lee

NOTES

-

Crawfurd, J. (1856). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries (p. 98). London: Bradbury & Evans. Microfilm nos.: NL 6554, NL 25418. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1971). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries. Kuala Lumpur, New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.8 CRA) ↩

-

Singapore. (1854, June 1). The Courier (Hobart, Tas: 1840–1859) (p. 2). Retrieved from Trove website. ↩

-

Descriptive dictionary of British Malaya. (1894, June 2). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩