The First English and Malay Dictionary

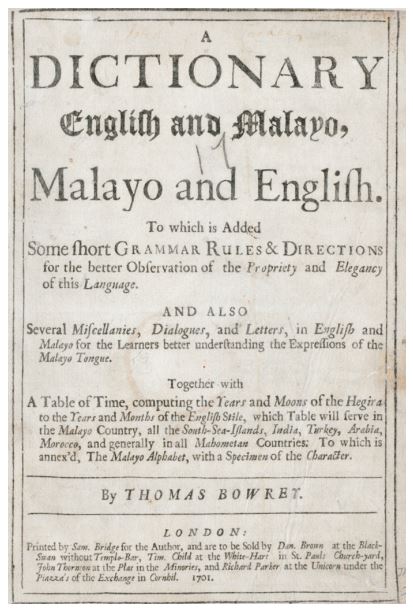

Title: A Dictionary: English and Malayo, Malayo and English

Author: Thomas Bowrey (1650–1713)

Year published: 1701

Publisher: Printed by Sam Bridge (London)

Language: Malay and English

Type: Book; 594 pages

Call no.: RRARE 499.3 BOW

Accession no.: B03061459F

The first-ever English and Malay dictionary was written by an unlikely swashbuckling British trader by the name of Thomas Bowrey.1 More interestingly, it was published in 1701, more than a century before Stamford Raffles even set foot in Singapore.

The hefty 594-page bi-directional dictionary – in English-Malay and Malay-English – includes 468 pages of words and definitions, a section on Malay rules of grammar as well as a compilation of miscellaneous phrases, sentences, dialogues and specimen letters.

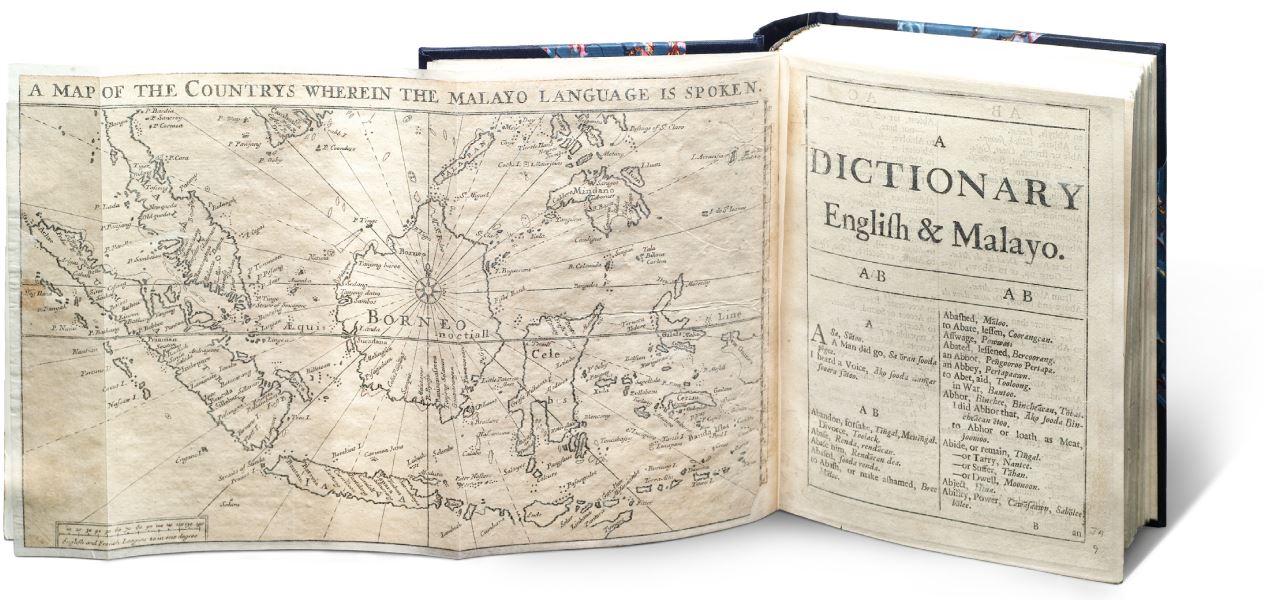

Both English and Malay words are listed in alphabetical order, a convention that is still used today. The dictionary also contains a double-page map titled “A Map of the Countrys wherein the Malayo Language is Spoken”, illustrating the geographical reach of the language in the 17th century.

Bowrey’s dictionary was a pioneering tool in the study of the Malay language. Not only was it the first dictionary of English and Malay published, it was also the first to use Roman letters instead of Jawi.2 This dictionary stood out as the only work of its kind until 1801, when James Howison published A Dictionary of the Malay Tongue as Spoken in the Peninsular of Malacca, the Islands of Sumatra, Jawa, Borneo, Pulau Pinang etc. in Two Parts, English and Malay, and Malay and English.3

Although the Dutch – who had a longer presence in the Malay Archipelago – had earlier published works on the Malay language that had been translated in the 17th century into English,4 these were not dictionaries. Bowrey’s work therefore bears the distinction of being the “first original independent publication by an English scholar in the Malay field”.5

Credit should be given to Bowrey for reproducing his practical experience with spoken Malay into a dictionary despite the relatively short intervals of time he spent in the Malay-speaking regions.6 Since Bowrey was likely not familiar with the written form, the Malay taught to him was not literary but idiomatic. The entries in his dictionary are therefore representative of the type of Malay used in conversations between British traders and local Malays at the time.7 To ensure the Malay words are pronounced correctly, Bowrey inserted accent marks above the vowels.8

The dictionary was probably useful in facilitating the already significant trade between British and local traders in the Malay world. In earlier decades, the Portuguese (1511) and later Dutch (1641) had invaded Melaka. Not only did trade thrive under the different colonial powers, the Malay language continued to be the lingua franca of trade in the East Indies.9

Bowrey, who spoke Malay fluently, made no bones about the fact that the pursuit of trade in the Malay-speaking countries was his biggest incentive for compiling the dictionary.10 John Leyden, a scholar of the Malay language, called the dictionary a work of “great merit and labour” a century after its publication,11 while Richard O. Winstedt in his book, Malaya (1923), said Bowrey’s grasp of working Malay was something “to be envied”. Stamford Raffles himself might have benefitted from Bowrey’s mastery. Winstedt wrote that when Raffles sought to bring himself up to speed in Malay during his long voyage to the East, he gleaned heartily from “some antediluvian book”. This book could very well be Bowrey’s dictionary.12

Bowrey, who left England in 1668 when he was barely 19 years old, likely compiled his dictionary during his return voyage home after trading in the Eastern Isles for almost 20 years. In 1688, Bowrey boarded the ship Bangala Merchant and with time on his hands during the long journey, likely scoured from his memory the vast working knowledge of Malay he had built up over the years from his travels.13 With no access to references, Bowrey’s corpus of Malay vocabulary was presumably culled from his interactions with the different people he had encountered in the region.

In publishing his dictionary, Bowrey had help from two eminent scholars who were well-versed in Malay: Thomas Hyde and Thomas Marshall.14 Hyde contributed a list of Malay words in the Jawi script to Bowrey’s dictionary.15 Bowrey completed a draft manuscript of his dictionary sometime in the late 17th century, and this draft was most probably the version he showed to the directors of the British East India Company, as he alludes to in the dedication of his work.16

Much of Bowrey’s private life was unknown until the discovery of his personal papers in a manor in Worcestershire, England, in 1913. Bowrey’s manuscripts and several hundred letters and business papers were later purchased by a Colonel Henry Howard, and part of it was presented to the Guildhall Library in London in 1931.17

– Written by Nor-Afidah Abdul Rahman

NOTES

-

Bowrey, T. (1927). The papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669–1713 (p. 38). R. C. Temple. (Ed.). London: Hakluyt Press. Call no.: RCLOS 910.8 HAK-[RFL] ↩

-

Bowrey, T. (1701). Preface. In A dictionary, English and Malayo, Malayo and English. (pp. 4–6). London: Printed by Sam Bridge. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Doshi, A. (1994). The development of the English/Malay Dictionary: A historical perspective (pp. 69–70). In B. & L. E. Newell. (Eds.), Papers from the First Asia International Lexicography Conference, Manila, Philippines, 1992. LSP Special Monograph Issue, 35. Retrieved from SIL International website; Howison, J. (1801). A dictionary of the Malay tongue as spoken in the Peninsular of Malacca, the islands of Sumatra, Jawa, Borneo, Pulau Pinang etc. in two parts, English and Malay, and Malay and English. London: Arabic and Persian Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Jones, R. (1984). Malay studies and the British. Archipel, 28, 120–121. Retrieved from Persee Revues Scientifiques website ↩

-

Jones, 1984, p. 127; Mee, R. (1929, September). An old Malay dictionary. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 7 (2) (107), 316. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Bialuschewski, A. (2007). Thomas Bowrey’s Madagascar manuscript of 1708. History in Africa, 34, 32–33. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Miller, G. (1991). Malay used by English country traders of the 18th century. Retrieved from Malay Concordance Project website. ↩

-

Doshi, 1994, p. 70. ↩

-

Liu, A. H. (2015). Standardizing diversity: The political economy of language regimes (p. 27). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Call no.: RSEA 306.44959 LIU ↩

-

Jones, 1984, p. 128. ↩

-

Mee, 1929, p. 316. ↩

-

Bowrey, 1927, pp. xvii, xxx; Rei, C. (2007, March 14). The organization of merchant empires: A case study of Portugal and England. Retrieved from Department of Economics, University of Boston website. ↩

-

Rost, R. (Ed.). (1886). Miscellaneous papers relating to Indo-China, (Vol. 1, p. 102). Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

Jones, 1984, p. 120. ↩

-

Mee, 1929, p. 316; Gallop, A. T. (2015, April 3). Early vocabularies of Malay. Retrieved from The British Library website. ↩

-

Bowrey, 1927; p. xxx; Bialuschewski, 2007, p. 31. ↩