A Bona Fide History Book

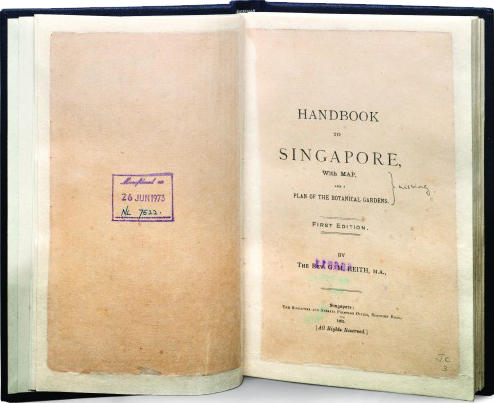

Title: Handbook to Singapore, with Map and a Plan of the Botanical Gardens

Author: George Murray Reith (1863–1948)

Year published: 1892

Publisher: The Singapore and Straits Printing Office (Singapore)

Language: English

Type: Book; 135 pages

Location: Call no.: RRARE 959.57 REI; Microfilm no.: NL7522

The title page of Handbook to Singapore, one of the first travel guidebooks to the city. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.

The title page of Handbook to Singapore, one of the first travel guidebooks to the city. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.Travel guides are more than just books that tell you about interesting sights in a destination, or where to eat, and how to get from one place to another. As a guidebook becomes worn and dated over time, it turns into a bona fide history book, providing valuable insights into the past. This is exactly what Handbook to Singapore has become: a history book of sorts documenting life in the colony in the late 19th century.

As travel became increasingly popular towards the end of the 1900s, guidebooks were published to fill a gap in the market. Sensing the need for one, Reverend George Murray Reith, resident minister of the Presbyterian Church in Singapore wrote a handy guide for visitors to the island.

Printed in 1892, Reith’s Handbook is one of the earliest tourist guides to Singapore. Although by no means the first guide about the island to be published, it was certainly the best of its kind at the time; earlier guidebooks such as The Stranger’s Guide to Singapore (1890) by B. E. D’Aranjo and Picturesque and Busy Singapore (1887) by T. J. Keaughran were described as “limited in… scope” or “too general to be of practical value” respectively.1 Handbook, however, provided enough information to be relevant to tourists even up to a century after it was first published. As a testament to its enduring relevance and value, the book was reprinted in 19072 and 1985.3

Handbook is divided into 15 chapters. The reader is given a brief overview of the history of Singapore, starting from Stamford Raffles’ landing on the island in 1819. Reith then sets the scene for the rest of the book, with sections on Singapore town and its environs, walking tours and drives, and descriptions of buildings, landmarks and places of worship.

Reith manages to include vivid imagery of life in turn-of-the-century Singapore in his book. In Chapter 4, interspersed with tour directions to the Botanical Gardens, Mount Faber and other attractions, he brings Singapore to life by detailing the leisurely lifestyle of expatriates alongside the menial labour work performed by natives.

View of Battery Road and the Tan Kim Seng fountain, early 1900s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

View of Battery Road and the Tan Kim Seng fountain, early 1900s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Also included in the book are useful listings of banks, consulates, religious buildings and hospitals as well as rates for hiring private and public carriages. Other sections on population, geography, wildlife and weather have become standard inclusions in modern guidebooks.

Reith’s appreciation for the Malay language was evident in Handbook. Malay colloquial place names (and pronunciation tips) were included in the book. A listing of Malay place names and their English counterparts are given in Chapter 9, revealing how locals viewed some of these colonial landmarks. For example, the Masonic Hall was known as “Rumah Hantu” or “Haunted House” and the Methodist Episcopal Church beside it was known as “Greja dekat Rumah Hantu” or the “Church near the Haunted House”.4

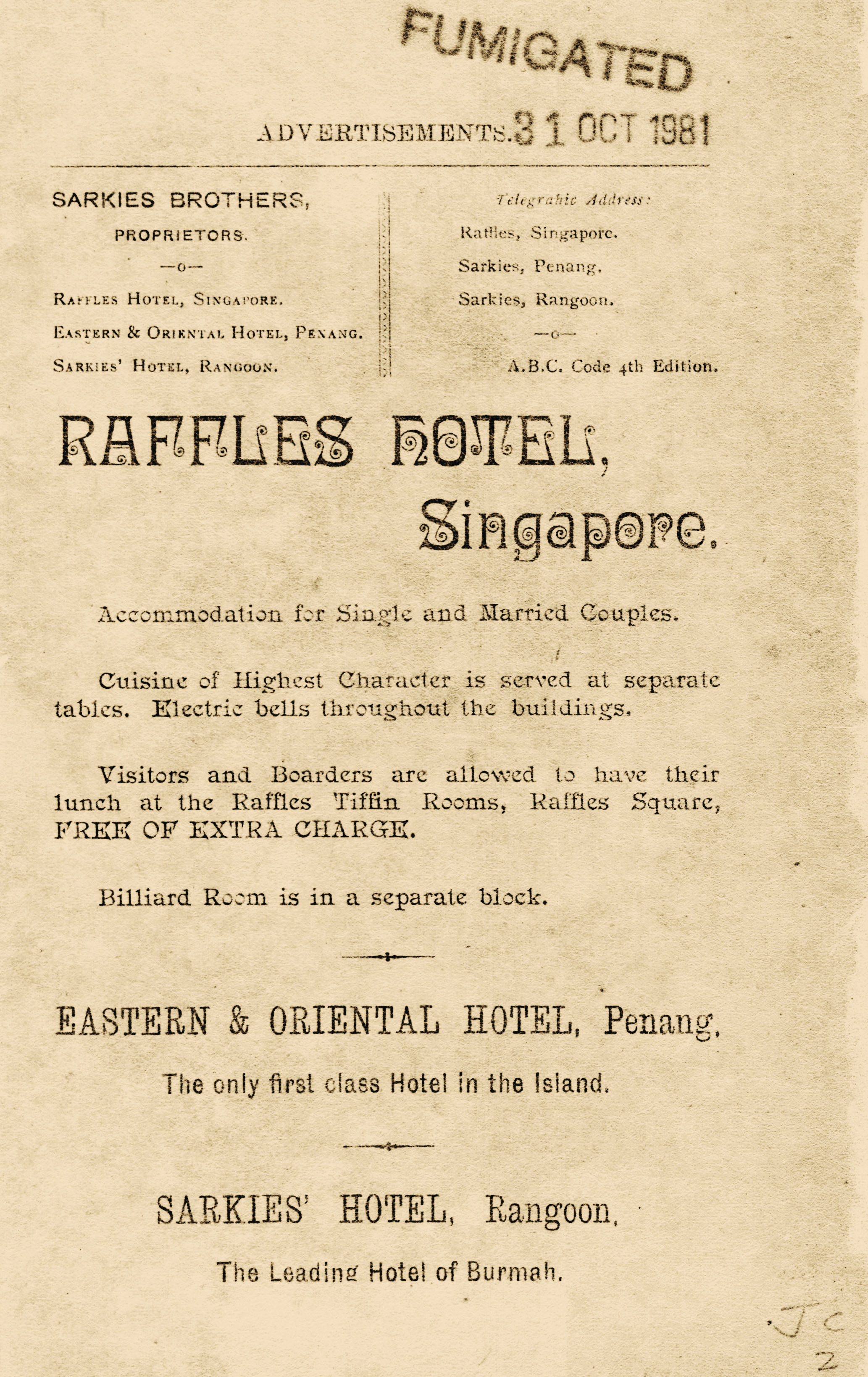

Although there are no photographs or illustrations, there is a map of Singapore with an accompanying index and a plan of the Botanical Gardens. Unfortunately, the map and plan are missing from the National Library’s copy of the book. Eleven pages of text-based advertisements round off the guide.

One of the advertisements in the book promoting the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, the Eastern & Oriental Hotel in Penang and the Sarkies’ Hotel in Rangoon. All three were owned by the famous Sarkies brothers. All rights reserved, Reith, G. M. (1892). Handbook to Singapore, with Map and Plan of the Botanical Gardens. Singapore: The Singapore and Straits Printing Office.

One of the advertisements in the book promoting the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, the Eastern & Oriental Hotel in Penang and the Sarkies’ Hotel in Rangoon. All three were owned by the famous Sarkies brothers. All rights reserved, Reith, G. M. (1892). Handbook to Singapore, with Map and Plan of the Botanical Gardens. Singapore: The Singapore and Straits Printing Office.In 1907, Walter Makepeace, a journalist and editor of The Singapore Free Press, published a new edition of the guide with updated information, a new chapter on the Federated Malay States and photographic plates of landmarks and sights in Singapore by G. R. Lambert & Co., besides providing the most current statistical data for 1907.5

As informative as Handbook might be, some historians have noted that it catered to the tastes of the Western expatriate. Paul Kratoska, in his introduction to the 1985 reprint of the book, wrote: “the attraction was not Asia but European activities and accomplishments in Asia.”6 Historian Constance Mary Turnbull in her review commented that Handbook was “heavily slanted towards the expatriate minority”, but said it was “more informative than modern counterparts” and “enterprising for its day in recommending strolls through the ‘native quarters’ and shopping forays into Rochor ‘Thieves Market’”.7

Born in 1863 in Scotland, Reith studied at Aberdeen University and New College, Edinburgh.8 He arrived in Singapore in 1889, and became minister of the Presbyterian Church here between 2 July 1889 and February 1896.9 Active in the Singapore community, Reith was the first secretary-treasurer of the Straits Philosophical Society.10 He was a frequent contributor to The Singapore Free Press, and published Padre in Partibus in 1897, a collection of writings about his travels in Java and Siam. Reith passed away in Edinburgh on 27 February 1948.11

– Written by Bonny Tan

NOTES

-

Reith, G. M. (1892). Handbook to Singapore, with map and a plan of the Botanical Gardens (p. iii). Singapore: Singapore and Straits Print. Office. Microfilm no.: NL 7522 ↩

-

Reith, G. M., & Makepeace, W. (1907). Handbook to Singapore with map. Singapore: Fraser and Neave. Microfilm nos.: NL 24341 and NL 30196 ↩

-

Reith, G. M., & Makepeace, W. (1985). Handbook to Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57 REI-[HIS] ↩

-

Reith & Makepeace, 1985, pp. v–vi. ↩

-

Turnbull, C. M. (1988, June). Reviewed work: 1907 Handbook to Singapore by G. M. Reith. The China Quarterly, 114, 301–302. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

National Library of Scotland. (n.d). Inventory Acc 3564 – Papers of the Rev George M. Reith. Retrieved from National Library of Scotland website. ↩

-

Johnson, A. (1988). The burning bush (p. 29). Singapore: Dawn Publications. Call no.: RSING 285.25957 JOH ↩

-

The Rev. G. M. Reith. (1896, February 28). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library of Scotland, n.d. ↩