Stories of Abdullah

Title: Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah)

Author: Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (Munsyi

Abdullah) (1797–1854)

Year published: 1849

Publisher: Mission Press (Singapore)

Language: Jawi

Type: Book; 443 pages

Call no.: RRARE Malay 959.503 ABD

Accession no.: B03014389F

Quite ironically, the most detailed account of Stamford Raffles’ momentous arrival in Singapore was captured by a man who was not even there. Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, better known as Munsyi Abdullah, gathered reports from those present to piece together a version of the events that occurred during Raffles’ first arrival to Singapore on 29 January 1819.1 This landmark narrative is included in his autobiography Hikayat Abdullah, or Stories of Abdullah, one of the most important records of the socio-political landscape in Singapore, Melaka and the southern Malay kingdoms of Johor and Riau-Lingga at the turn of the 19th century.

Written in Jawi – modified Arabic script used to write the Malay language – between 1840 and 1843 and published in 1849, the book is considered compulsory reading among scholars of Malay literature and culture and is the most renowned of Abdullah’s works.2 Until the 1970s, it was used as a textbook in every Malay school in Singapore.3

Born in Melaka in 1797, young Abdullah studied under the best Malay scholars in his hometown and read all the Malay manuscripts he could find. By the time he was 11, the child prodigy was already making money from writing Qur’anic texts and teaching religion to Indian soldiers stationed in Melaka. The soldiers called him “munsyi”, which means “teacher of language” – a title he would carry for the rest of his life. By 14, Abdullah had become an accomplished Malay scholar.4 He went on to teach Malay to some of the most eminent administrators, scholars and missionaries in the Straits of Melaka, including Raffles.5

As a scribe and interpreter for Raffles, and a Malay teacher to several English personages, Abdullah had a front-row seat to the political and cultural developments of the time. His perceptive insights, combined with a penchant for vivid descriptions, would give future readers of his book a rich picture of 19th-century life and personalities in Singapore and the region.6

Among other things, the Hikayat chronicles the three changes of the European guard in Melaka, the establishment of the British settlement in Singapore in 1819, Sultan Husain Shah’s brief rule during the early days of the settlement, and the eventual ceding of the island by the sultan and temenggung of Johor to the East India Company. The autobiography captures the breathless pace of Singapore’s development as a trading port under the British Empire, recounting the construction of new infrastructure, the boom in commerce, and the influx of immigrants that led to the island’s multi-racial population.7

Departing from the courtly tradition of Malay texts, Abdullah adopted a journalistic tenor that suited his forthright views. His passages are realistic and lively, incorporating many Malay idioms and proverbs.8 The unusually conversational tone was inspired by the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), a book about the history of the Melaka Sultanate in the 15th and early 16th centuries. Abdullah had edited a version of Sejarah Melayu while working for Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, a Protestant missionary and noted leader in Malay education and in printing.9

It was another missionary and printer, Alfred North, who encouraged Abdullah to write an account of the Malay people – including traditional Malay stories, customs, prejudices and superstitions – that would interest the Europeans.10 In this effort, Hikayat Abdullah succeeded splendidly – it became the best-known Malay literary work among Europeans.11

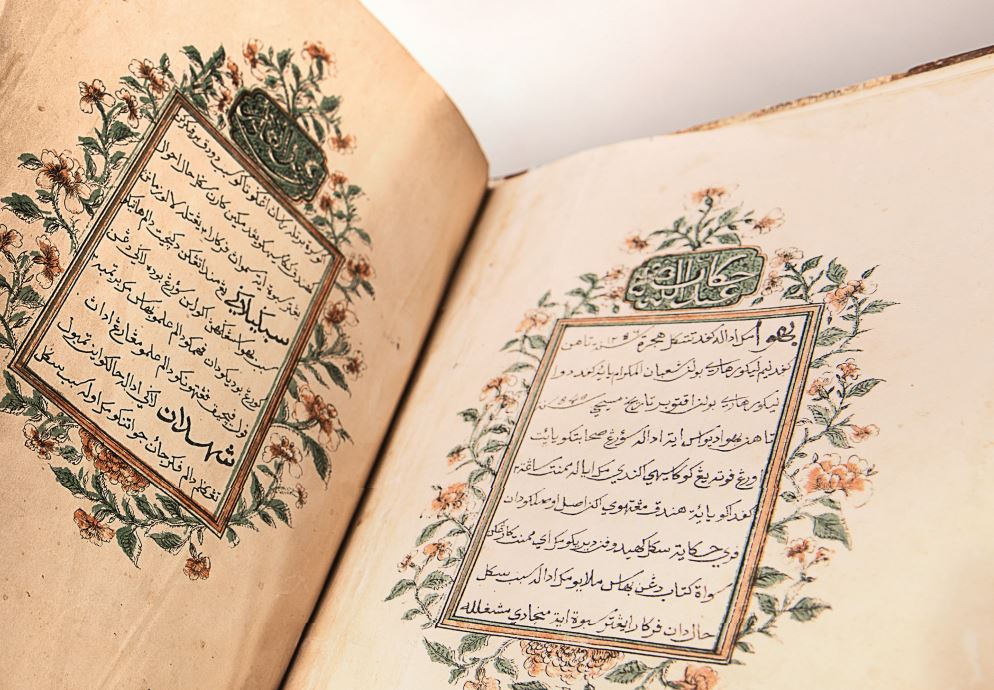

Abdullah was the first local to have his works published in Malay, earning him the reputation of the “father of modern Malay literature”.12 In recent times, however, Abdullah has also been called a stooge of the British for his pro-British views.13 Regardless, he certainly earned the epithet “father of Malay printing.” He and Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen introduced printing to Singapore when they arrived from Melaka in 1822. Abdullah’s works would have been beautiful editions even then – Hikayat’s fine calligraphy and beautifully coloured double frontispiece made it among the most impressive Malay works ever printed in the Straits Settlements.14

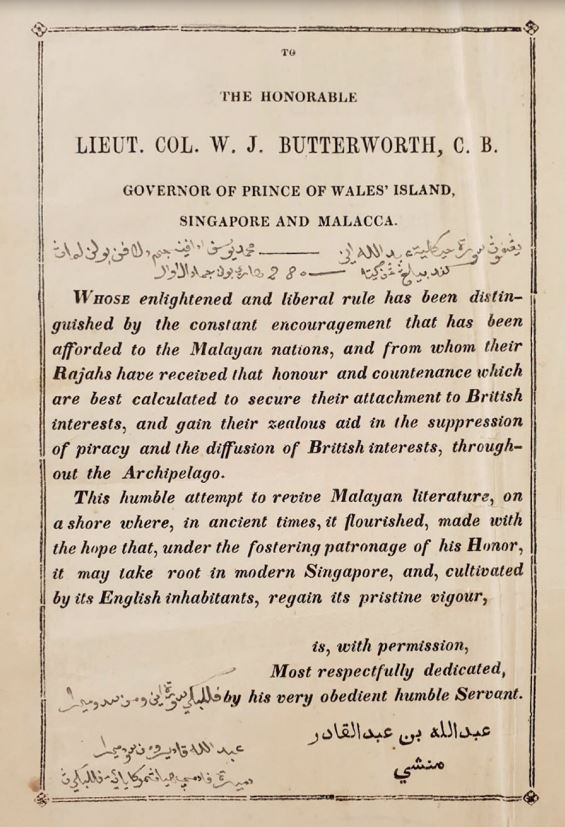

This copy of the Hikayat Abdullah, which carries a dedication in English to William J. Butterworth, governor of the Straits Settlements from 1843–55, was one of two artefacts the National Library submitted to the “Treasures from the World’s Great Libraries” exhibition held from 2001–02 at the National Library of Australia in Canberra.15

Munsyi Abdullah died in Mecca in 1854 while on pilgrimage.16 But his legacy is assured: Hikayat Abdullah is a lasting milestone in modern Malay literature.

– Written by Ang Seow Leng

NOTES

-

National Library of Australia (2001). Treasures from the world’s great libraries (p. 108). Canberra: National Library of Australia. Call no.: R q025.1 TRE-[LIB]. ↩

-

Reith, G. M. (1892). Handbook to Singapore, with map and a plan of the Botanical Gardens (pp. 132–133). Singapore: Straits Print. Office. Microfilm no.: NL 7522. ↩

-

Kennard, A. (1970, September 28). Some brilliant reporting on our history. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir Munshi. (2009). The Hikayat Abdullah; an annotated translation by A. H. Hill; with foreword by Cheah Boon Keng (pp. 8–9). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Call no.: RSEA 959.5 ABD. ↩

-

Gallop, A. T. (1990). Early Malay printing: An introduction to the British Library collections. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (1) (258), 98. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Anuar Othman. (1993, January 4). Historical Malay works in Chinese. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Traill, H. F. O’B. (1979). An Indian protagonist of the Malay language: Abdullah “Munshi”, his race and his mother-tongue. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 52 (2) (236), 81. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Azizah Sidek & Mazelan Anuar. (2008, January). Hikayat Abdullah. BiblioAsia, 3 (4), 35–36. ↩

-

Abdullah, 2009, pp. v, 22; National Library Board. (1998). Benjamin Keasberry written by Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; UNESCO Memory of the World. (n.d). Sejarah Melayu (The Malay Annals). Retrieved from UNESCO website. ↩

-

Che-Ross, R. (2002). Malay Manuscripts in New Zealand: The ‘lost’ manuscript of the “Hikayat Abdullah” and other Malay manuscripts in the Thomson collection. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 75 (2) (283), 18. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Reith, 1892, p. 132. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2001). Munshi Abdullah written by Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Sweeney, A (2006, November). Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munsyi: A man of bananas and thorns. Indonesia and the Malay Word, 34 (100), 223–245. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩

-

Gallop, 1990, pp. 96–97. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2001/2002). Annual report (p. 24). Singapore: National Library Board. Call no.: RCLOS q027.05957 SNLBAR-[AR]. ↩

-

Che-Ross, R. (2000, July). Munshi Abdullah’s voyage to Mecca: A preliminary introduction and annotated translation. Indonesia and the Malay World, 28 (81), 182. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩