A Dictionary That Bridged Two Races

Title: Hua yi tong yu (华夷通语)

Author: Lin Hengnan 林衡南 (also known as

Lim Kong Chuan 林光铨)

Year published: 1883

Publisher: Koh Yew Hean Press 古友轩(Singapore)

Language: Chinese (Southern Min dialect)

Type: Book; 252 pages

Call no.: RRARE Chinese 499.23824151 LHN

Accession no.: B03018482D

Donated by: Tan Yeok Seong

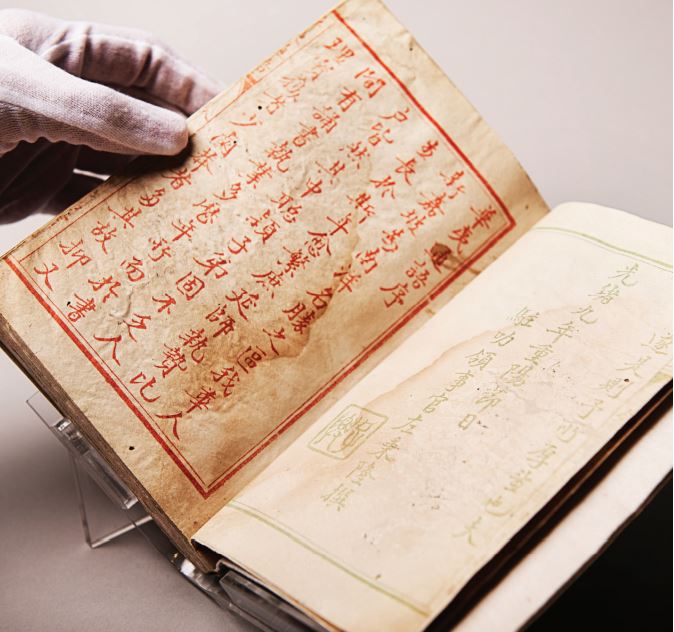

Right-hand page: Zuo Binglong (左秉隆), the first Chinese Consul to Singapore appointed by the Qing Imperial Court in China, signed off the foreword, which was written during the Double Ninth Festival in 1883. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.

Soon after Singapore gained independence in 1965, the government announced that English would be the lingua franca that would unite the linguistically diverse population. But attempts to forge a common language in Singapore had begun as early as the 19th century, when Chinese migrants to Singapore – the majority of whom spoke Southern Min dialects (闽南语) such as Hokkien1 – tried to communicate with the Malay-speaking indigenous population. Several Chinese-Malay dictionaries – listing Malay words with their equivalent terms in Chinese – were produced in the 19th century.2 One of the earliest was Hua yi tong yu (华夷通语), published in 1883.

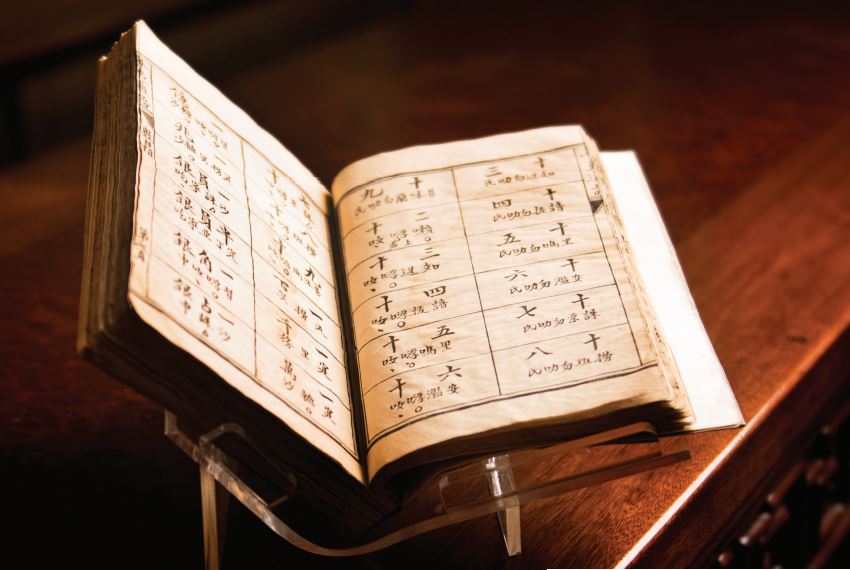

This earliest known Singapore-published Chinese-Malay dictionary in the National Library’s collection contains more than 2,800 entries in 25 categories. The entries include terms used in disciplines such as cosmology and geography to mathematics as well as common business terms. The second section categorises the entries according to the number of Chinese characters contained in each term, while the third and final section lists verbs and adjectives that could not be categorised in the preceding two sections.3

In the preface penned by Zuo Binglong (左秉隆), the first Chinese Consul to Singapore appointed by the Qing Imperial Court, the writer explains that the dictionary was necessary because large numbers of Chinese migrants had settled in Nanyang (南洋 or the “South Seas”) to trade with the Malays in the region. Since the migrants – mainly from the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou regions of Fujian province and Chaozhou in Guangdong province – could not conduct their business effectively due to their inability to speak Malay, a dictionary was needed.

The author, Lin Hengnan (林衡南), came up with an ingenious solution by devising a system that uses native Southern Min dialects to phoneticise Malay words. The dictionary teaches users how to pronounce Malay words by using Chinese characters that sound similar when said in the Southern Min dialects.4 For example, to learn the Malay word satu, which means “one”, Lin used the Chinese characters “沙诛” – pronounced sha zhu in Mandarin but sa tu in Hokkien. Tiga, or “three”, is “知迓” – pronounced zhi ya in Mandarin but ti ga in Hokkien.5

To render the phoneticisation more accurate, Lin indicated the tone of the Chinese character to be used when pronounced using Southern Min dialects. He also switched between the tones of the Zhangzhou, Quanzhou and Chaozhou dialects as needed to ensure that the words were pronounced correctly in Malay.6

The first edition of the dictionary was published as Tong yi xin yu (通夷新语) in 18777 (unfortunately the National Library does not own a copy of this). Lin wrote in his introduction that he had originally compiled the dictionary for his newly arrived fellow countrymen in Singapore. It was only through the encouragement of a friend, Chen Fengren (陈凤人) from Chaozhou, that he decided to publish the dictionary.8 For modern-day readers, Hua yi tong yu serves as a historical record of words in the Southern Min dialects that are either obsolete or rarely used today.

An in-depth study of the text reveals that many expressions and sentence constructions – a mix of written vernacular Chinese (bai hua;白话), classical Chinese (wen yan;文言), Mandarin (guan hua;官话) and dialect (tu hua;土话) – that were unique to that era – are no longer commonly used today. Linguists who have studied Hua yi tong yu agree that the dictionary helps to track the evolution of borrowed Malay words in the Southern Min dialects and vice versa, a phenomena spurred by prolonged interactions between the migrants and locals.9

Linguistic insights aside, the dictionary also provides an anthropological snapshot of the lives of these new Chinese residents. The entries include shipping terms and the names of different parts of a ship and the tools used onboard – reflecting the importance of trade in their lives – as well as the names of various types of food and fruits, illnesses, herbs and household items.10

The dictionary was edited by Li Qinghui (李清辉) and published by Lin’s own publishing house, Gu You Xuan (古友轩), also known as Koh Yew Hean Press, established in the 1860s on Telok Ayer Street.11

Lin wrote other books, and in 1890, founded the Chinese newspaper called Xing bao (星报).12 After Lin died, the newspaper was taken over by his son who eventually sold it to Lim Boon Keng. The latter renamed it Ri xin bao (日新报) in 1899.13

– Written by Lee Meiyu

NOTES

-

Straits Settlements Department of Statistics. (1883). Blue Book (p. P6). Singapore: Government Printing Office. Microfilm no.: NL 30780 ↩

-

张嘉星. (2002). 印尼、新、马闽南方言文献述要. 漳州师范学院学报(哲学社会科学版), 3, 73–74. Retrieved from CNKI. ↩

-

李如龙. (1998). 华夷通语研究. 方言, 2, 105–106. Retrieved from CNKI. ↩

-

林衡南. (1883). 华夷通语序. 华夷通语. 新加坡: 古月轩. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

李如龙, 1998, pp. 106, 108–122. ↩

-

李如龙, 1998, pp. 106, 108–122. ↩

-

李如龙, 1998, pp. 106, 108–122. ↩

-

李如龙, 1998, pp. 105-106. ↩

-

林衡南, 1883, 华夷通语序; 郑文辉 [Zheng, Wenhui]. (1973). 新加坡华文报业史: 1881–1972 [Xinjiapo Hua wen bao ye shi: 1881–1972] (pp. 25–26). 新加坡: 新马出版印刷公司 [Xinjiapo: Xin ma chu ban yin shua]. Call no.: RCLOS 079.5957 CWH-[AKS] ↩

-

叶观仕编著 (1999). 马新华人录 (1806 – 2000) (pp. 27–28). 吉隆坡: 名人出版社. Call no.: RSING q070.922595 WHO ↩