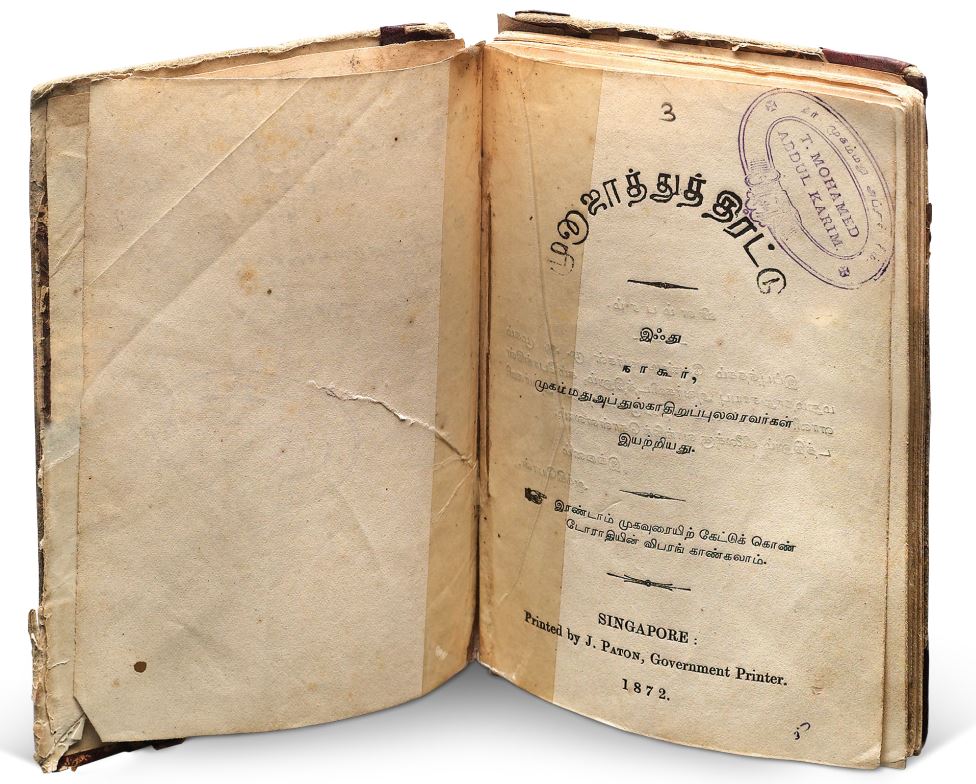

Indian Muslim Devotional Poems

Title: Munajathu Thirattu (முனாஜாத்துத்

திரட்டு)

Author: Muhammad Abdul Kadir Pulavar

(முகம்மதுஅப்துல்காதிறு, நாகூர், புலவர்)

Year published: 1872

Publisher: J. Paton, Government Printer (Singapore)

Language: Tamil

Type: Book; 105 pages

Call no.: RRARE 894.81114 MUH

Accession no.: B18835673H

The early Indian Muslims who settled in Singapore in the 1800s brought with them a varied heritage: their skills as shopkeepers and office workers, their unique customs and beliefs, and a tradition of devout poetry.1 Indeed, their religious faith was a key source of solace for these transplanted Muslims from the southern part of India, who often expressed their piety in the form of verse. One particularly notable poet among them was Muhammad Abdul Kadir Pulavar, whose Islamic religious poetry collection, Munajathu Thirattu, is the oldest Tamil book held by the National Library.

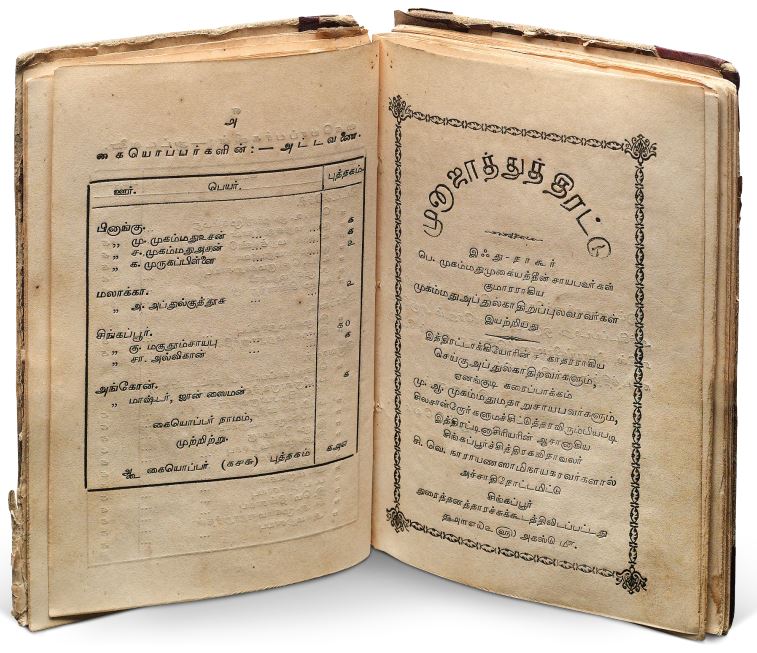

Published by J. Paton, Government Printer, in 1872, the book comprises a total of 55 poems and songs in praise of Muslim saints and the Prophet Muhammad. The verses are written in simple Tamil, richly overlaid with Persian and Arabic words, and are appended with tunes and rhythms. They are divided into six genres: introductory poems in praise of the author (four poems); Munajathu Pathikam (four songs); Thanippaakkal (12 poems); Thanippathangal (30 songs); Sindhu, a lyrical form of Tamil (two poems); and Chitirak Kavi, graphical poems in which the letters are drawn in such a way that they resemble the shape of snakes, chariots and other pictographs (three poems).

The collection takes its name from the Arabic word munajat – meaning a private and intimate talk with Allah – which is derived from the terms yunaji or najawa, meaning “talking in secret”. The word najawa in turn has its roots in najah, which means “deliverance” or “salvation”. Hence, the book’s title conveys the meaning of “supplication for the repentance of sins”. Its poems glorify God and offer humble prayers in the form of simple but expressive verses.2

Among them is a song written in praise of Sikkandar Sahib Oli, better known as Sultan Iskandar Shah, who is believed to be the last of five kings to rule over 14th-century Singapore. A descendent of Sang Nila Utama (the legendary founder of Singapore who predates Stamford Raffles), Iskandar Shah is supposedly buried in a terrace on the northern side of Fort Canning, a spot which has since become a holy place of worship.3

Munajathu Thirattu is also noteworthy as evidence of the island’s tolerant multiracial character from as early as the 1800s. Although this is an Islamic religious poetry collection, we see a beautiful introductory poem by the well-known Hindu poet C. V. Narayanasamy Nayagar, who was also the teacher of the book’s author Muhammad Abdul Kadir.

Tamil and Malay journalism in Malaya owe their origins to “locally born Indian Muslims in Singapore, or to be more exact, the community known as “Jawi Peranakan” according to Southeast Asian scholar William Roff.4 The Jawi Peranakan group in Singapore owned a few presses and published Tamil newspapers and books.5

Also among the Jawi Peranakan community was philanthropist Makathum (also spelled as Makhdum) Sahib bin Ghulam Mukhyuddin Sahib, who together with Muhammad Abdul Kadir, founded a newspaper in 1875.6 The paper, Singai Vardhamani – also called Singavartamaney or Singapore Commercial News – earned a place in history as the earliest known Tamil newspaper in Singapore. According to a description in the Straits Times Overland Journal, the tiny foolscap paper-sized newspaper was neatly printed in clear type and included fine content selections, short editorials and listings of weekly prices and bank exchange rates.7 Makathum Sahib, who owned the Denodaya Venthira Press, also ran another newspaper called Singai Nesan in the late 1880s. He encouraged writers in their work and published their creative efforts himself.8

Not much else is known about Muhammad Abdul Kadir, save that he was the son of P. Muhammad Muhayatheen Sahib from Nagore, in Tamil Nadu, India, and that he studied under the aforementioned C. V. Narayanasamy Nayagar. According to a brief note in the publication Malasiya Tamil Kavitaik Kalanjiam,9 Narayanasamy was known as “Cingapur Chithira Kavi”, which implies he was famous for writing graphical poems.

The National Librar y’s copy of Munajathu Thirattu was purchased in 2005 from Jaffar Mohideen, an Islamic scholar, writer, poet and journalist, who also came from the same Indian hometown of Nagore as Muhammad Abdul Kadir.

– Written by Sundari Balasubramaniam

NOTES

-

National Heritage Board. (2015, July 2). Former Nagore Dargah. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Mumtaz Ali Tajddin S. Ali (2002, August 5). Introduction of the munajat (Ya Ali Khub Majalis). Retrieved from Ismaili Net website. ↩

-

Forbidden Hill of beauty. (1984, March 7). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Roff, W. R. (1967). The origins of Malay nationalism (p. 48). Singapore: University of Malaya Press. Call no: RCLOS 320.54 ROF-[SEA] ↩

-

Feener, R. M., & Sevea, T. (Eds.). (2009). Islamic connections: Muslim societies in South and Southeast Asia (pp. 93–94). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Call no: RSING 297.0954 ISL ↩

-

Bala, Baskaran. (2010, December 18). சி வீ குப்புசாமியும், வாழ்க்கை வரலாறும், 1967ஆம் ஆண்டு மலாயாத் தமிழ் எழுத்தாளர் சங்க ஆண்டு விழா உரையும். Retrieved from Balabaskaran blogpspot. ↩

-

Friday 9th June. (1876, June 10). Straits Times Overland Journal, p 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

இலங்கைத் தமிழ்மணி மானாமக்கீன் (2013, Mar). இஸ்லாமியத் தமிழ் இலக்கியத்தின் இணையம் இன்றல்ல. Retrieved from Mudukulathur website. ↩

-

நெடுமாறன், முரசு [Muracu. Neṭumār̲an̲]. (1997). மலேசியத் தமிழ்க் கவிதைக் களஞ்சியம்: 1887–1987 [Malēciyat Tamil̲k kavitaik kaḷañciyam: 1887–1987] (pp.581–582). சிலாங்கூர்: அருள்மதியம் பதிப்பகம் [Cilāṅkūr: Aruḷmatiyam Patippakam]. Call no: R 894.8111 MAL. ↩