Raffles' Political Manoeuvres

Title: Letter from Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles to John Tayler

Author: Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)

Year written: 9 June 1819

Language: English

Type: Manuscript; 4 pages; 26cm by 21cm

Call no.: RRARE 959.5703 RAF

Accession no.: B18835716F

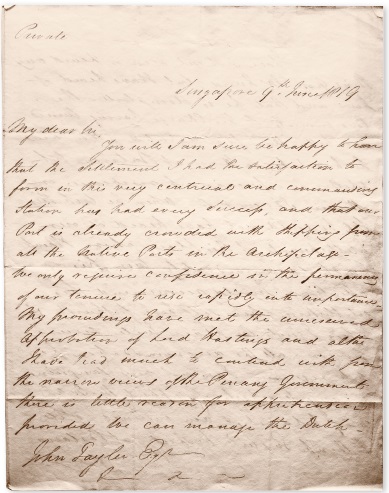

This is the first letter by Stamford Raffles acquired by the National Library in 1987. Dated 9 June 1819, the letter was addressed to John Tayler, his business agent and friend. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.

This is the first letter by Stamford Raffles acquired by the National Library in 1987. Dated 9 June 1819, the letter was addressed to John Tayler, his business agent and friend. Image source: National Library Board, Singapore.Among the 19 letters held in the Rare Materials Collection of the National Library is one from Stamford Raffles to his business agent and friend, John Tayler, a London-based East India merchant. Interesting, this is also the first letter by Raffles that the National Library acquired in 1987.

This handwritten letter is slightly unusual in the sense that it reveals Raffles’ private thoughts to a confidant and friend, and offers his first-hand insights into the rivalry between the British and the Dutch in the Malay Archipelago.

In the letter, Raffles expresses his frustration at being undermined by his supervisor, Colonel John Alexander Bannerman, the Governor of Penang, who was determined to keep Penang’s leadership within his fold at all costs. Raffles’ grievances confirmed the stiff competition between the two British trading posts of Singapore and Penang.1 By holding on to Penang, Bannerman effectively robbed Raffles of his ambition to advance his career in the Far East.

The letter was written during Raffles’ second visit to Singapore from May to June 1819,2 a few months after he had successfully signed a treaty with Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor and Temenggong Abdul Rahman on 6 February 1819 to set up a British outpost in Singapore.

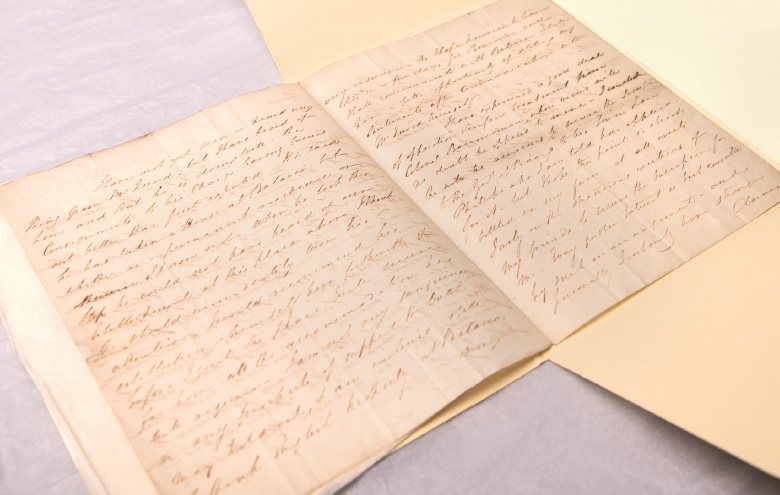

The letter was written during Stamford Raffles’ second visit to Singapore from May to June 1819. Raffles confides in his friend and business agent, John Tayler, and expresses his frustration at being undermined by his supervisor, Colonel John Alexander Bannerman. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The letter was written during Stamford Raffles’ second visit to Singapore from May to June 1819. Raffles confides in his friend and business agent, John Tayler, and expresses his frustration at being undermined by his supervisor, Colonel John Alexander Bannerman. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Those early days were tumultuous times for Singapore, and the letter testifies to the island’s precarious situation. Four months after the treaty was signed with the Malay chiefs, Singapore’s status as a British trading post was still disputed by the Dutch. The news of Singapore’s founding soon reached London in August 1819, and the “paper war”3 that ensued served to remind both the British and Dutch of the inconclusive settlement of the 1814 London Convention in mediating Anglo-Dutch relations in the East. However, Raffles did not waver even in the face of Dutch anger.4 His “confidence in the permanency of our tenure” was noted in his letter, which eventually led to a more permanent truce in the Malay Archipelago with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty on 17 March 1824.

Raffles continued to face opposition from his own side as he tried to establish a foothold in the Far East. A strong opponent to his political manoeuvres was his superior, Colonel Bannerman. The Penang authorities had fought bitterly against the founding of Singapore, which they knew would pose a serious threat to the trade in Penang. At the peak of his resistance, Bannerman refused to send military reinforcements to Singapore when it faced possible Dutch expulsion, and the rift between the two deepened when Raffles’ bid for Bannerman’s post in Penang conflicted with the latter’s plans to pass the baton to his son-in-law, William E. Phillips.

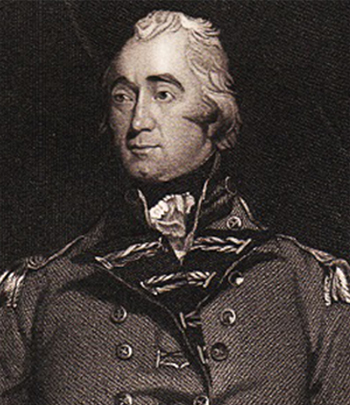

Colonel John Alexander Bannerman (1759–1819), Governor of Penang from 1817–19. All rights reserved, Cartwright, A., & Cartwright, H. A. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (p. 23). London: lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, Ltd.

Colonel John Alexander Bannerman (1759–1819), Governor of Penang from 1817–19. All rights reserved, Cartwright, A., & Cartwright, H. A. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (p. 23). London: lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, Ltd.The loss of Java to Holland in 1816 had divested Raffles of a position of high status and power, as he was previously the Lieutenant-Governor of Java,5 and the rivalry for the Penang post was alluded to in Raffles’ letter, where he justified his “stronger claims” over Bannerman’s familial stake in the governorship.6

When Bannerman died on 8 August 1819, Phillips was sworn in as acting governor. Raffles, when informed of Bannerman’s death two months later, immediately sailed to Calcutta to pitch for the Penang governorship. But his optimism slowly faded with the Governor-General of India Lord Hastings’ wait-and-see approach on London’s verdict regarding Singapore. The Penang succession was eventually settled in favour of Bannerman’s son-in-law,7 and a dejected Raffles retreated into a quiet life in Bencoolen. He resigned from the British East India Company in 1822 due to poor health.

Portrait of Francis Rawdon-Hastings, First Marquess of Hastings (1754–1826). This is an 1829 engraving by Roger Griffith and R. J. Beevor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Francis Rawdon-Hastings, First Marquess of Hastings (1754–1826). This is an 1829 engraving by Roger Griffith and R. J. Beevor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.In 2001, this letter was displayed in Canberra at the National Library of Australia’s “Treasures from the World’s Great Libraries” exhibition from December 2001 to February 2002.8 It was one of two treasures on loan by the National Library, the other being the 1849 edition of the Hikayat Abdullah.9 By that time, almost 15 years after its purchase, the value of the letter had doubled.

In 2012, the letter was transcribed by Dr John Bastin, an eminent scholar and a leading authority on Raffles. The transcript was published in a book by Bastin titled The Founding of Singapore, 1819, published by the National Library Board (NLB) in conjunction with the exhibition, “Raffles’ Letters: Intrigues Behind the Founding of Singapore” held at the National Library Gallery from 29 August 2012 to 28 February 2013.10 In 2014, the book was republished as Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore by NLB and Marshall Cavendish Editions.

– Written by Nor-Afidah Abdul Rahman

NOTES

-

Turnbull, C.M. (2002). Penang’s changing role in the Straits Settlements, 1826–1946 (p. 4). The Penang Story – International Conference 2002. Retrieved from Taman Sri Nibong RA Log website. ↩

-

Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore River: A social history, 1819–2002 (p. 7). Singapore: Singapore University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOB-[HIS] ↩

-

Glendinning, V. (2012). Raffles and the golden opportunity 1781–1826 (p. 234). London: Profile Books. Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 GLE-[HIS] ↩

-

Webster, A. (1998). Gentlemen capitalists: British imperialism in South East Asia, 1770–1890 (pp. 88–100) London; New York: Tauris Academic Studies. Call no.: RSING 959 WEB ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2012). The founding of Singapore 1819 (pp. 128–129). Singapore: National Library Board. Call no.: RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS] ↩

-

Glendinning, 2012, pp. 228–231. ↩

-

National Library of Australia. (2001). Treasures from the world’s great libraries. Retrieved from National Library of Australia website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2002). Annual report 2001/2002 (p. 24). Singapore: National Library Board. Call no.: RCLOS 027.05957 SNLBAR-[AR] ↩