Raffles’ Letters of Intrigue

Title: Letters from Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles to Lord Lansdowne

Author: Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)

Year written: 15 April 1820; 19 January 1821; 1 March 1822; 20 January 1823

Language: English

Type: Manuscript; 25cm by 20cm

Call no.: Call no.: RRARE 959.5703 RAF

Accession nos.: B20072355B; B20072356C;

B20072357D; B20072358E

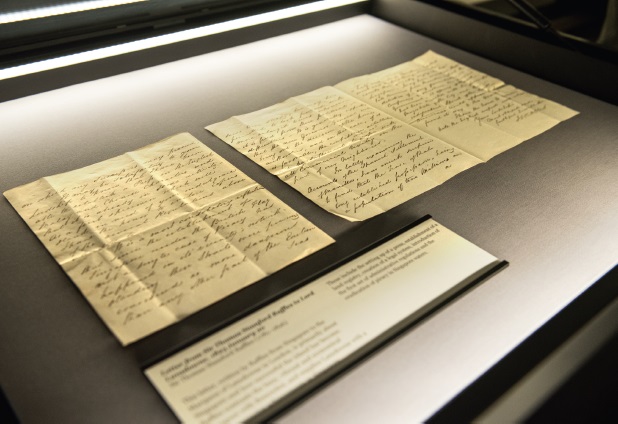

A letter from Stamford Raffles to Lord Lansdowne on display at the National Library’s Rare Collections Gallery on level 13 of the National Library Building. There are a total of 19 letters penned by Raffles in the possession of the National Library. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

A letter from Stamford Raffles to Lord Lansdowne on display at the National Library’s Rare Collections Gallery on level 13 of the National Library Building. There are a total of 19 letters penned by Raffles in the possession of the National Library. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Singapore was almost not founded by Stamford Raffles. Four letters that detail Raffles’ passionate defence to establish a British trading outpost on the island in 1819 offer insight into the objections he faced from the Dutch as well as his own British masters. Written between 1820 and 1823 to Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, the letters reveal the lengths that Raffles went to persuade his superiors at the British East India Company (EIC) of Singapore’s achievements and its growing importance as a regional trading hub.

The first letter (17 pages) was dated 15 April 1820; the second letter (15 pages) 19 January 1821; the third (12 pages) 1 March 1822; and the fourth (7 pages) 20 January 1823.

It was a precarious time for the newly established settlement. Even though Raffles had signed a treaty with Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor and Temenggung Abdul Rahman on 6 February 1819 to establish a trading post on the island, the move was opposed by the Dutch, who argued that Singapore, as part of Riau’s territories, was rightfully theirs. However, Raffles knew that acquiring a trading point south of Malacca was the only way to counter the rise of the Dutch and to maintain Britain’s position in the India and China trade route.1

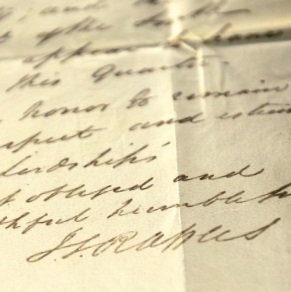

The signature of Stamford Raffles can be clearly seen at the bottom of this letter. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The signature of Stamford Raffles can be clearly seen at the bottom of this letter. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Even within the ranks of the EIC, Raffles’ decision was challenged. The political climate in London favoured reconciliation with the Dutch. Another formidable opponent of Raffles was Colonel John Alexander Bannerman, the Governor of Penang and Raffles’ immediate supervisor. Whether for personal reasons or fear of military confrontation with the Dutch, Bannerman vehemently opposed Raffles’ efforts to develop Singapore as a British settlement.2

It was against this hostile backdrop that Raffles wrote to Lord Lansdowne for his support. Lansdowne, who had been introduced to Raffles by Charlotte Seymour, Duchess of Somerset, in 1817, shared many common interests with Raffles, including succeeding the latter’s position as President of the Zoological Society of London between 1826 and 1831. Like Raffles, Lansdowne too wanted to keep Singapore under the British flag.3

Raffles first wrote to Lansdowne on 15 April 1820 about Singapore:

– When I hoisted the British flag the population scarcely amounted to 200 souls, in three months the number was not less than 3,000, and it now exceeds 10,000 principally Chinese – No less than 173 sail of vessels of different descriptions, principally Native, arrived & sailed in the course of the first two months, and it already has become a Commercial Port of importance –4

Raffles reiterated his vision for advancing British interests in the east, and complained about the difficulties he encountered from the Governor of Penang.5 In his second letter written on 19 January 1821, Raffles again emphasised Singapore’s success as a free port:

– Singapore which instead of a minor Station has turned out on experiment to be the most important in the Eastern Seas, naturally engages my chief attention – and I am happy to say our Establishment there has succeeded beyond all possibility of calculation – In point of Commercial importance it already rivals Batavia, and its whole charge scarcely exceeds £10,000 a year, ten times which amount might be collected were I to allow of the Collection of even moderate duties –6

Despite Singapore’s success, its fate rested in the hands of the political leaders in London.7 On 1 March 1822, Raffles again wrote to Lansdowne describing Singapore’s progress:

I have much satisfaction in reporting that my Settlement of Singapore still continues to advance, steadily but yet rapidly – The certainty of its permanent retention by us is alone wanting to ensure its prosperity – From the enclosed Abstract of Tonnage, your Lordship will be able to judge of the extent and nature of the Trade that is carried on –8

Raffles expressed in this third letter his wish to visit Singapore again. Fearing his poor health, he saw this as his last chance to do something for Singapore before retiring to England, and to address questions about its development, particularly with regard to land allocation and law and order.9

In September 1822, Raffles assumed direct responsibility for the administration of Singapore.10 On this last visit to Singapore, he wrote the fourth letter on 20 January 1823, in which he provided Lansdowne with a list of his achievements:

With the view of establishing a landed interest as far as the anticolonial principles of the Court of Directors will admit, I have open’d a Register for all land bought into Cultivation and provided for the Magistracy from the body of European Residents… It may be satisfactory to your Lordship to know that I have been able to establish a Press in the English[,] Malay and Chinese Characters and that it is already in some activity… It is a most consolatory reflection that since the establishment of Singapore under the British Flag not a single case of Piracy has happened in its vicinity;…11

However, Raffles remained anxious over whether Singapore would continue as a British settlement. This issue was not resolved until the following year, when the Dutch withdrew objections to the British occupation of Singapore with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty on 17 March 1824.12

In 2012, these four letters were part of an exhibition displaying 20 letters written by Raffles. The exhibition, “Raffles’ Letters: Intrigues Behind the Founding of Singapore”, was held at the National Library Gallery from 29 August 2012 to 28 February 2013. The letters, transcribed by Dr John Bastin, an eminent scholar and a leading authority on Raffles, were published in a book that Bastin authored called The Founding of Singapore 1819, produced by the National Library Board in conjunction with the exhibition. In 2014, the book was republished as Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore by NLB and Marshall Cavendish Editions.

– Written by Ong Eng Chuan

NOTES

-

Glendinning, V. (2012). Raffles and the golden opportunity 1781–1826 (p. 209). London: Profile Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 GLE-[HIS]); Turnbull, C.M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (p. 29). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

Glendinning, 2012, p. 207; Tan, K., & Chen, S. (2012). Raffles’ letters: Intrigues behind the founding of Singapore (p. 75). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 TAN-[HIS]) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2014). Raffles and Hastings: Private exchanges behind the founding of Singapore (pp. 210–211). Singapore: National Library Board Singapore [and] Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]); Tan & Chen, 2012, p. 19. ↩

-

Bastin, 2014, p. 158; Tan & Chen, 2012, p. 23. ↩