About Babas and the Chinese

Title: The Manners and Customs of the

Chinese of the Straits Settlements

Author: Jonas Daniel Vaughan (1825–91)

Year published: 1879

Publisher: Mission Press (Singapore)

Language: English

Type: Book; 119 pages

Call no.: RRARE 390.0951 VAU

Accession no.: B03061460I

Donated by: Tan Yeok Seong

The Peranakan Museum in Armenian Street is probably the best place to go if you want to learn about the origins, history and culture of Singapore’s fascinating Straits Chinese or Peranakan community.

But there was no such museum or repository of information more than a century ago. And so for the most part, people looked to a book written in 1879 by Jonas Daniel Vaughan, in which the social customs, religious practices and recreational activities of the Straits-born Chinese in British Malaya are described. Titled The Manners and Customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements, the book is part of the Ya Yin Kwan Collection that was donated to the National Library in 1964.

At barely 120 pages long, Vaughan’s work cannot be described as exhaustive. In fact, his writings have been criticised as rambling and uneven, with an obvious ethnocentric bias typical of the expatriate writing of the time. Despite its limitations, however, the book offers a useful glimpse of Baba Chinese culture during British colonial rule in the 19th century.1 And, as a first-hand account of early Singapore, the book’s ethnographic data will likely interest students of the Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.2

Popularly referred to as Peranakan (or Peranakan Cina, the Malay term for Chinese Peranakan), the Babas trace their ancestry to early Southern Chinese traders who settled in Melaka in the 16th century and married Malay women, and subsequently also in Penang and Singapore, the three areas designated by the British as the Straits Settlements in 1826. Over time this hybrid community adopted and adapted local customs and practices as well as those of the Europeans, so that by the mid-19th century, the Peranakans had become distinct from the Chinese and other local communities.

The core of Vaughan’s book is based on an early paper he wrote in 1854 on “Notes on the Chinese of Pinang”, published in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago, volume VII.3 It was expanded in 1879 to include observations and hearsay accumulated during Vaughan’s 45 years of colonial service in Penang and Singapore.

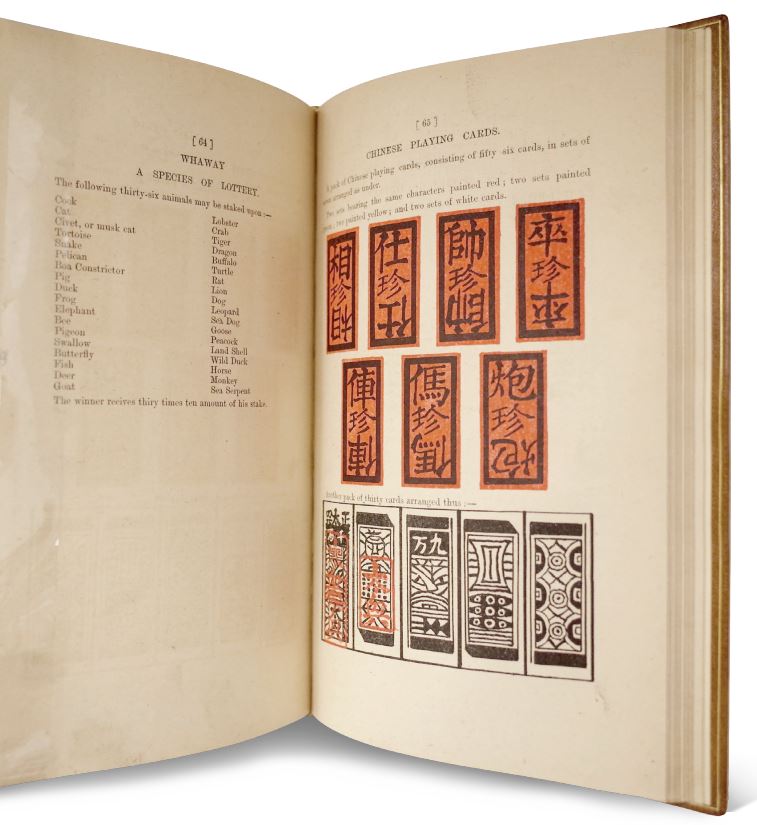

About a quarter of the book is devoted to descriptions of Peranakan ritual behavior, with short sections on topics such as the Chinese community’s domestic habits, drama, superstitions and secret societies. A section on gambling includes illustrations of Chinese playing cards and descriptions of the games, many of which are seldom seen today.

The concluding chapter on secret societies is by far the book’s most substantial contribution to our understanding of the Chinese community in general. Its value, in part, lies in the special position of the author, who as a police magistrate maintained a close relationship with the many factions of the Triad Society (Thian Ti Hui) and had insider knowledge of their activities. The chapter contains a comprehensive description of the society’s initiation rites and a list of rules that make up the charter of another formidable Chinese triad – the Ghee Hok Society.4

Overall, despite Vaughan’s ethnocentric approach and his tendency to overgeneralise and regard all Chinese as a homogeneous ethnic group, the book is significant for providing a baseline from which researchers can compare festivals, domestic habits and rites of passage with those practised by the Chinese in Malaya as well as other areas of Southeast Asia at the time.5 These keen observations have made the book a valuable resource and it was reprinted twice over a century later by Oxford University Press, in 1971 and 1974.

Born in 1825, Vaughan was a sailor who became a public official and later, a prominent lawyer in colonial Singapore. He joined the Bengal Marine in 18416 as a midshipman and stopped over in Singapore in 1842 while en route to China to fight the First Opium War (1839–42).7 After the war, he was posted to the Straits region and participated in the capture of Brunei and the destruction of pirate strongholds in Northwest Borneo.8 He was later appointed superintendent for Penang, Master Attendant of Singapore, a police magistrate, and finally, Assistant Resident Councillor before entering private service.9 In October 1891, Vaughan disappeared at sea while returning to Singapore from Perak and was presumed to have fallen overboard. Vaughan Road was named after him in 1934.10

– Written by Lee Meiyu

NOTES

-

Fortier, D. H. (1974, September). Review. American Anthropologist, 76 (3), 611. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Fortier, Sep 1974, p. 611; Blythe, W. (1971). Introduction. In J. D. Vaughan. (1971), The manners and customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements. Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 390.0951 VAU-[CUS]. ↩

-

Vaughan, J. D. (1879). The manners and customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements (p. 4). Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG; Blythe, 1971, Introduction. ↩

-

Kaufman, H. K. (1972, November). Review. The Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (1), 215–216. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

One Hundred Years of Singapore gives the date as 1842. See Makepeace, W., Brooke, G. E., & Braddell, R. St. J. (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 223). Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57ONE-[HIS] ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, C. A. (1960, May). The Master Attendants at Singapore, 1819–67. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 33 (1) (189), 57. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke & Braddell, 1991, p. 223. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, May 1960, pp. 58–62. ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke & Braddell, 1991, p. 224. ↩