Legends of the Malay Kings

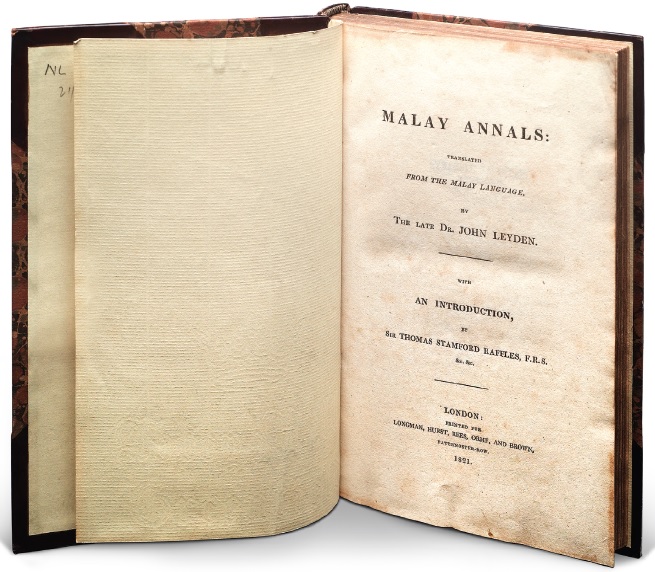

Title: Malay Annals (Sejarah Melayu)

Author: John Leyden (1775–1811), with an introduction by Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)

Year published: 1821

Publisher: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown (London)

Language: English

Type: Book; 361 pages

Location: Call no.: RRARE959.503 MAL

Accession no.: B02633069G

Title: Sejarah Malayu (Malay Annals)

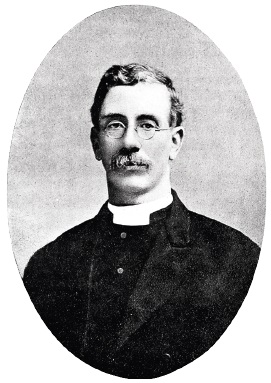

Author: William Girdlestone Shellabear (1862–1948)

Year published: 1898

Publisher: American Mission Press (Singapore)

Language: Romanised Malay

Type: Book; 190 pages

Call no.: RRARE 959.5 SEJ

Accession no.: B20025340E

Sejarah Melayu includes an introduction by Stamford Raffles and was used as a study aid to groom British scholar administrators in the colonial service. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

Sejarah Melayu includes an introduction by Stamford Raffles and was used as a study aid to groom British scholar administrators in the colonial service. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.The Sejarah Melayu is considered by scholars as an important literary work on the history and genealogy of the Malay kings of the Melaka Sultanate (1400–1511). Partially composed in the 17th century in Jawi – the modified Arabic script used to express the Malay language – the title is derived from its original Arabic name, Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings).1 But few are aware that its first English translation in the early 19th century, the Malay Annals, was actually undertaken by a Scotsman.

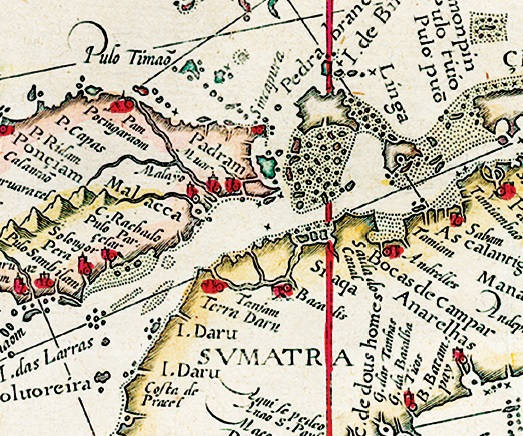

The close-up of the 1596 hand-coloured map Exacta & Accurata Delineatio cum Orarum Maritimdrum tum etjam locorum terrestrium quae in Regionibus China, Cauchinchina, Camboja sive Champa, Syao, Melaka, Arracan & Pegu… showing the location of Melaka – the heart of the Melaka Sultanate between 1400 and 1511. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The close-up of the 1596 hand-coloured map Exacta & Accurata Delineatio cum Orarum Maritimdrum tum etjam locorum terrestrium quae in Regionibus China, Cauchinchina, Camboja sive Champa, Syao, Melaka, Arracan & Pegu… showing the location of Melaka – the heart of the Melaka Sultanate between 1400 and 1511. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.His name was John Leyden, a close friend of the founder of modern Singapore, Stamford Raffles, and a prominent figure of the Scottish Enlightenment movement of the late 18th century.2 The book, published in 1821, is the earliest English translation of the epic work, and opened up the world of Malay history and literature to 19th century colonial scholars. In some ways, the book was so revolutionary that it overshadowed the handwritten Jawi manuscript, as well as the printed Jawi version by the learned scholar Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (also known as Munshi Abdullah), published 20 years later.3 In fact, the popular use of the translated title “Malay Annals” and the original “Sejarah Melayu” may be attributed to Leyden as both were likely coined in his translation.4

John Leyden (1775–1811) translated the Jawi text of the Sejarah Melayu into English in 1821. This is the earliest English translation of the epic work. All rights reserved, Bastin, J. (2002). Olivia Mariamne Raffles. Singapore: Landmark Books.

John Leyden (1775–1811) translated the Jawi text of the Sejarah Melayu into English in 1821. This is the earliest English translation of the epic work. All rights reserved, Bastin, J. (2002). Olivia Mariamne Raffles. Singapore: Landmark Books.Comprising 361 pages, the book includes an introduction by Raffles. It was considered important reading for potential British scholar-administrators well into the 20th century. A newer English translation by Charles Cuthbert Brown would only be published in 1953.5

Despite its significance today, early responses to the book were not all favourable. Part of it had to do with the content itself, which touched on the legends of the Malay kings as told from the perspective of the ruling class and based on memory.6

A review by Gentleman’s Magazine in January 1822 commented on the mix of “wild and unpolished” legends and events in the book even though it was given weight by Raffles’ introduction.7

In 1823, The Eclectic Review magazine called the work “a strange jumble of preposterous fiction”… “much heavier than the worst nonsense that has ever issued from the press”.8

A Straits Times review dated 5 April 1953 noted that although Leyden’s work was valuable in some aspects, it was “largely a paraphrase rather than a translation, and it was based on an incomplete manuscript”.9

Still, there is little doubt among scholars and historians of the importance of Leyden’s work, and that it was created through the dedication and hard work of its eccentric author. Born in Scotland to a poor shepherd, Leyden was a priest in the Church of Scotland before going to India to take up the post of Assistant Surgeon with the British East India Company (EIC) after undergoing a crash course in medicine.10

Leyden became well-known as an Orientalist who impressed with his linguistic prowess, confessing to have mastered over 20 languages.11 His initial encounter with the Malay language was in 1804 and a year later, he sailed to Penang, where he met the newly arrived Raffles and his wife Olivia. Raffles shared Leyden’s enthusiasm for the Malay language and the latter soon became Raffles’ inspiration in his Malay studies.12

Leyden’s confidence in Malay and other Southeast Asian languages led to his book, A Comparative Vocabulary of the Burma, Malayu and Thai Languages, which was printed in 1810.13 It is believed that he started on the translation of the Sejarah Melayu around the same time that A Comparative Vocabulary was released, and that he completed it by the time he sailed with Lord Minto – the Governor-General of India – from Calcutta to Melaka in April 1811.14

Leyden was assisted by a Malay scribe, whom he had met in Penang. “Ibrahim, son of Candu [Kandu]” was said to have made a copy of the epic work in Melaka, and brought it with him to Calcutta in 1810. There, Ibrahim read and explained the Jawi text to Leyden, who wrote down what he thought was “worthy of notice”.15 When Ibrahim left with Raffles for Penang at the end of October 1810, it was assumed that by then, Leyden had completed the translation, and was planning to improve it.16

Unfortunately, Leyden died the following year on 28 August. His books, private papers, manuscripts and translations were shipped to Calcutta by his executors. However, Raffles kept many of Leyden’s materials, including the Malay Annals, until he left Java for London in 1816 and likely handed the translation to Leyden’s cousin, Reverend James Morton. Raffles provided Morton with information on Leyden’s life and agreed to write an introduction to the Malay Annals, which he completed in 1817.17

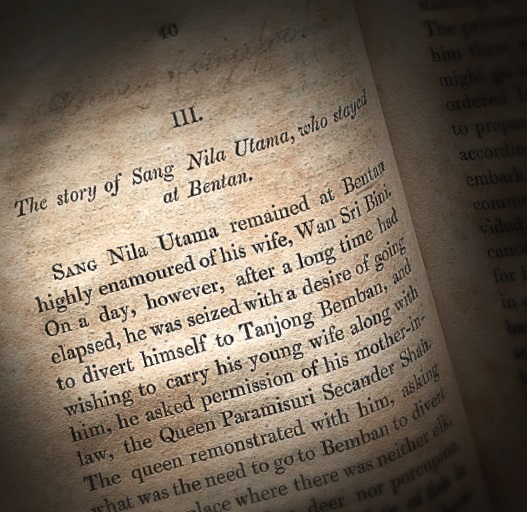

The legend of Sang Nila Utama, a prince from Srivijaya who supposedly founded Singapura (Singapore), is one of the stories featured in the Sejarah Melayu. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The legend of Sang Nila Utama, a prince from Srivijaya who supposedly founded Singapura (Singapore), is one of the stories featured in the Sejarah Melayu. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.W. G. Shellabear’s Version

Also part of the National Library’s collection is the 1898 romanised Malay version of the Sejarah Melayu translated by William Girdlestone Shellabear, who had come to Singapore in 1886 as a soldier, but later found amity with the Malay soldiers he led as a result of his Christian faith. After learning the Malay language and joining the Methodist Mission in Singapore as a missionary, Shellabear produced several texts to reach out to the Malay community, mainly Christian works translated into Malay that would be used as a means of attracting Malays to the Methodist Church.

William G. Shellabear (1862–1947) translated his own Jawi version of the Sejarah Melayu into romanised Malay in 1898. All rights reserved, Makepeace, W., Brooke, G. E., & Braddell, R. St. J. (1921). One Hundred Years of Singapore (Vol. II). London: John Murray. W. G. Shellabear’s Version.

William G. Shellabear (1862–1947) translated his own Jawi version of the Sejarah Melayu into romanised Malay in 1898. All rights reserved, Makepeace, W., Brooke, G. E., & Braddell, R. St. J. (1921). One Hundred Years of Singapore (Vol. II). London: John Murray. W. G. Shellabear’s Version.Shellabear’s interest in the Sejarah Melayu and other Malay classical works that he subsequently published was motivated by his plan to provide refined Malay literature for training missionaries in Malay language and culture.18

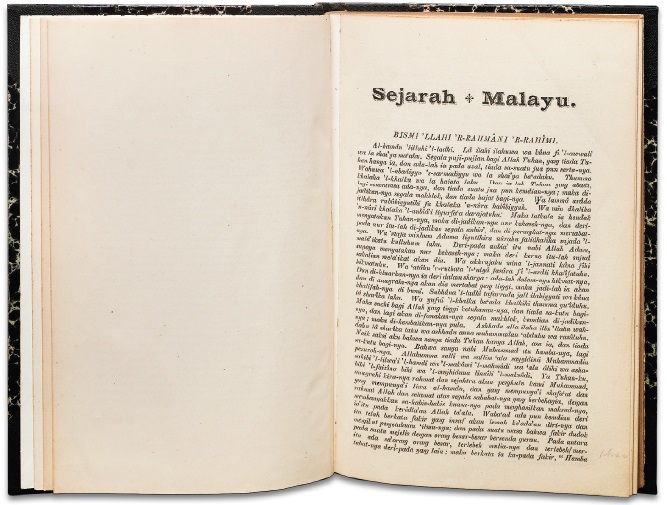

An inside page of the romanised Malay version of the Sejarah Melayu, translated by William G. Shellabear. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

An inside page of the romanised Malay version of the Sejarah Melayu, translated by William G. Shellabear. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Published in Singapore by the American Mission Press, Shellabear’s romanised Malay edition was based on his own Jawi version published two years earlier. The romanised edition was deemed useful for the vernacular schools,19 and was followed by a second edition in 1910,20 released as a literature textbook that became widely used in schools. The existence of other editions in several languages, including French and German, testifies to the enduring popularity of the Sejarah Melayu.21

– Written by Nor-Afidah Abdul Rahman

NOTES

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. (2015). Sejarah Melayu. Retrieved from Encyclopaedia Britannica website; The British Library Board. (2013, September 13). Sejarah Melayu: A Malay masterpiece. Retrieved from British Library website. ↩

-

Van der Putten, J. (2007, February). Review: Between iron formalism and playful relativism: Five recent studies in Malay writing. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 38 (1), 147–163, p. 159. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Van der Putten, Feb 2007, p. 158; Ibrahim bin Ismail. (1986, September). The printing of Munshi Abdullah’s edition of the Sejarah Melayu in Singapore. Kekal Abadi, 5 (3), 17. Retrieved from University of Malaya Library website. ↩

-

Van der Putten, Feb 2007, p. 160. ↩

-

Shepard, M.C. (1953, March 30). Candid saga of Malaya’s past. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hooker, V.M. (1998, September 30). Malaysia as history: The tenth James C. Jackson memorial lecture. Retrieved from Australian National University website. ↩

-

Malay Annals, translated from the Malay language, by the late Dr John Leyden, with an introduction by Sir Stamford raffles, F.R.S. (1822, January–June). The Gentleman’s Magazine, 92 (1), 45–46. Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language. (1823, July–December). The Eclectic Review, 18 , 285. Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

A Malay classic – in English now. (1953, April 5). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hannigan, T. (2012). Raffles and the British invasion of Java (p. 51). Singapore: Monsoon Books. (Call no.: RSEA 959.82 HAN) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2002). John Leyden and the publication of the “Malay Annals”. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 75 (2) (283), 99–115, p. 103. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Hannigan, 2012, p. 55. ↩

-

Bastin, 2002, p. 106. ↩

-

Bastin, 2002, p. 107. ↩

-

Bastin, 2002, p. 107. ↩

-

Van der Putten, Feb 2007, p. 159; Bastin, 2002, pp. 107–108. ↩

-

Bastin, 2002, p. 110–112. ↩

-

Hunt, R. A. (2002, January). The legacy of William Shellabear. International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 26 (1), 29–30. Retrieved from International Bulletin Organisation website. ↩

-

Malay Annals. (1898, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (p. 465). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO) ↩

-

Ibrahim bin Ismail, Sep 1986, p. 1. ↩