Singapore’s First School

Title: Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823

Author: Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)

Year published: 1823

Publisher: Mission Press (Malacca)

Language: English

Type: Book; 110 pages

Call no.: RARE 373.5957 FOR

Accession no.: B20025196C

The cover and title page of the Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823. The Singapore Institution was eventually renamed the Raffles Institution around 1868. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The cover and title page of the Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823. The Singapore Institution was eventually renamed the Raffles Institution around 1868. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.The founding of Raffles Institution (originally known as Singapore Institution) was fraught with difficulties and delays from the very beginning. It all started with this document – a 110-page record of a meeting held on 1 April 1823, in which Stamford Raffles laid down his plans to establish a school for Asians. First published in 1819 as On the Advantage of Affording the Means of Education to the Inhabitants of the Further East,1 the document reveals Raffles’ vision of Singapore as a hub not only in trade but also in learning. This was forward thinking at a time when even basic education was still not formally implemented in England.2

With the exception of Quranic instruction3 and a few Chinese schools in Penang and Melaka, formal education was sorely lacking in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula.4 In this document, purchased by the National Library in 2006, Raffles puts forth his rationale for starting an institution of learning dedicated to the education of the Malay elites as well as employees of the British East India Company.5

The proposal pertaining to its founding can be read from pages 34 to 42, which document the history of the Anglo-Chinese College in Melaka. On pages 53–59 is the detailed proposal by its founder, the missionary Robert Morrison, to relocate the college to Singapore and incorporate it with the planned Singapore Institution.6 The proposed incorporation of Anglo-Chinese College led to plans for two separate colleges within the institution: one for Chinese and another for Malay, Thai and other local cultures. A third scientific college would be set up later.

Robert Morrison, the missionary who started the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca, was one of the founding fathers of the Singapore Institution. Painting by John Richard Wildman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Robert Morrison, the missionary who started the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca, was one of the founding fathers of the Singapore Institution. Painting by John Richard Wildman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.The rest of the document concerns details on how the proposed institution would function, including regulations governing student admissions; the administration of the library, museum and printing press; as well as staffing and appointment of patrons and trustees. The last three pages (108–110) list the names of subscribers and donors, and the amounts pledged to start the school. The total sum donated amounted to 17,495 Spanish dollars, including pledges of 1,000 Spanish dollars each by Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman, members of the Johor empire that ruled Singapore.

William Farquhar, the first British Resident of Singapore, supported Raffles’ plan. He donated 1,000 Spanish dollars towards the project,7 and was originally slated to run the school. Ironically, Raffles replaced Farquhar with John Crawfurd as the second Resident on 9 June 1823, who opposed using East India Company funds for the school and withheld the 4,000 Spanish dollars that Raffles had committed.8 Instead, Crawfurd proposed setting up elementary schools.9 The death of Raffles three years later in 1826 ended the proposed partnership with the Anglo-Chinese College.10

Fortunately, a memorial fund came to the rescue in 1832, providing funds to start the Singapore Free School in 1833 with John Henry Moor as headmaster. In 1837, the school moved into its new premises along the seafront Bras Basah Road (where Raffles City today stands) and became known as the Singapore Institution Free School.11

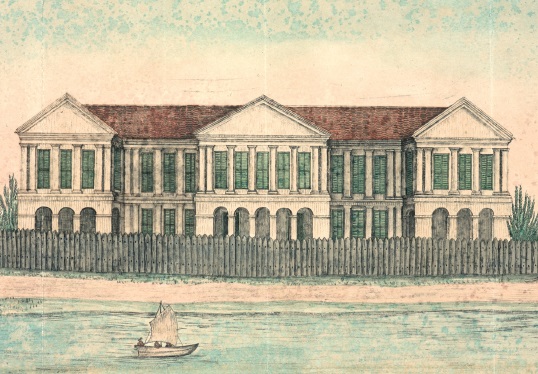

An 1841 watercolour painting of the since demolished Singapore Institution along the seafront at Bras Basah Road by J. A. Marsh. © The British Library Board, WD 2969.

An 1841 watercolour painting of the since demolished Singapore Institution along the seafront at Bras Basah Road by J. A. Marsh. © The British Library Board, WD 2969.Thus was Singapore’s first school founded, not as a higher education institution as Raffles and Morrison had envisioned, but to provide more foundational basic education.12 In 1856, it was renamed Singapore Institution, and remained so for at least a decade until the school’s annual report for 1868 referred to it as the Raffles Institution.13

Raffles’ views on education, gambling, slavery and other such issues of his time mirrored the views of what is today seen as the progressive reformers of early 19th-century British society. Such views were in contrast to more conservative sectors of British society who were not in favour of promoting education beyond the elite.

Today, the school that has been renamed Raffles Institution has churned out some of the nation’s brightest minds, and ironically viewed by some, fairly or unfairly, as an institution for the elite.

– Written by Timothy Pwee

NOTES

-

Bastin, J.S. (1999). The first printing of Sir Stamford Raffles’s minute on the establishment of a Malay college at Singapore (p. 2). Eastbourne: J. Bastin. (Call no.: RCLOS 370.9598 RAF-[JSB]) ↩

-

Hind, R.J. (1984, Summer). Elementary schools in nineteenth-century England: Their social and historiographical contexts. Historical Reflections/ Réflexions Historiques, 11 (2), 189–205. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Harrison, B. (1979). Waiting for China: The Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca, 1818–1843, and early nineteenth-century missions (pp. 132–133). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 207.595141 HAR) ↩

-

Lee, T.H. (2011). Chinese schools in Peninsular Malaysia: The struggle for survival (p. 3). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSEA 371.8299510595 LEE) ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1823). Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823 (pp. 5–38). Malacca: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Wijeysingha, E. (1989). The eagle breeds a gryphon: The story of the Raffles Institution 1823–1985 (pp. 33–44, 335–338). Singapore: Pioneer Book Centre. (Call no.: RSING 373.5957 WIJ) ↩

-

Wijeysingha, 1989, pp. 33–44. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, pp. 431–432). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]); Singapore Institution Free School. (1862). Report (Singapore Institution Free School), 1834–62 (p. 3). Singapore: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Wijeysingha, 1989, pp. 57–64. ↩

-

Buckley, C. B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (p. 139). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]) ↩