Living it Up at the Capitol

Capitol Theatre was the premier venue for film and stage when it opened in 1930. Bonny Tan uses oral history recordings to piece together pre-war narratives of the theatre.

Capitol Theatre and the adjoining Namazie Mansions at the junction of Stamford Road and North Bridge Road, c.1950. By 1946, the new owners had replaced the sign “Namazie Mansions” with “Shaws Building”. In 1992, it was renamed Capitol Building. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Capitol Theatre and the adjoining Namazie Mansions at the junction of Stamford Road and North Bridge Road, c.1950. By 1946, the new owners had replaced the sign “Namazie Mansions” with “Shaws Building”. In 1992, it was renamed Capitol Building. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Capitol Theatre opened to much fanfare on 22 May 1930, marking the dawn of a new era in entertainment and lifestyle in Singapore. Although there were several existing cinemas, such as the Alhambra and Marlborough, the Capitol sought to be the epitome of the high life in the city by showcasing the best in both film and live performances. Completed at the outset of the Great Depression, the Capitol was instrumental in transforming Singapore’s entertainment landscape in more ways than one.

Dressed to the Nines

The idea of building a high-end theatre for both stage and screen was conceived by S.A.H. Shirazee, an Indian-Muslim merchant and community leader. The Capitol boasted the largest seating capacity for a theatre in the Far East at the time – with 1,100 seated on the ground floor and another 500 upstairs − and the very latest in technology and comfort. Adjoining it was a complex with high-end shops on the ground floor and 48 apartments occupying two upper floors.

The Capitol was commissioned and financed by Mirza Mohammed Ali Namazie, a well-known Persian businessman. Besides managing various business ventures, Namazie was himself a film buff, having been the distributor of UFA, a German film agency, since 1919.1

Capitol Theatre was commissioned and financed by Mirza Mohammed Ali Namazie, a well-known Persian businessman. He had moved to Singapore from Madras, India, in the 1910s to set up M.A. Namazie & Co. Courtesy of Mirza Mohammed Ali Namazie.

Capitol Theatre was commissioned and financed by Mirza Mohammed Ali Namazie, a well-known Persian businessman. He had moved to Singapore from Madras, India, in the 1910s to set up M.A. Namazie & Co. Courtesy of Mirza Mohammed Ali Namazie.Many people have mistaken the distinctive street-facing façade as the theatre, a perception created by the gigantic movie billboard hanging over the entrance to the building. In actual fact, what is visible at the corner of Stamford and North Bridge roads is the four-storey complex of apartments and shops known as Namazie Mansions. Early photos of the building show “Capitol Theatre” emblazoned above the billboard with “Namazie Mansions” in smaller typeface above it. The actual theatre, a rather nondescript-looking structure from the outside, is found at the rear of the building.

Namazie Mansions was built in November 1929, a few months before the theatre behind it was completed in February 1930. The total construction cost of the theatre and apartment complex amounted to 1.25 million Straits dollars. The theatre took up two-thirds of the cost as it incorporated the latest innovations in cinema and theatre technology.

Designed by British architects P.H. Keys and F. Dowdeswell and constructed by Messrs Brossard and Mopin, the architects drew inspiration from Roxy Theatre in New York. Capitol had the largest projection room in the world when it opened, extending the length of the building and housing the latest Simplex deluxe projectors. Located below the balcony was the projection room, built entirely of reinforced concrete, a newly introduced construction material.

The theatre also featured an innovative ventilation system in which purified, cooled air was blown into the auditorium without the aid of fans, while its domed roof could be opened to let in fresh air, except on rainy days. Most importantly, Capitol was the first cinema in Singapore to be purpose-built for talkies. It was installed with state-of-the-art soundproofing, acoustics and sound systems – constructed just as this new genre of film was becoming popular.2

The Capitol was dressed to the nines – as was expected of its patrons – with wider and more luxuriously upholstered seats, multi-hued lights that cast a magical glow on the silk drapings on stage, and even the latest in wall paint to allow easy cleaning. Changing rooms and organ chambers were also built into the theatre to facilitate stage productions.

Much of the external and interior design was influenced by Joe Fisher (see text box below), a South African who had been in the film industry for more than two decades. Fisher was instrumental in bringing in the latest Hollywood films and theatrical performances that helped cement Capitol as Singapore’s premier entertainment venue. Namazie, Shirazee and Fisher formed Capitol Theatres Ltd, which ran the business, with Namazie as the company chairman, Shirazee as director, and Fisher as managing director.

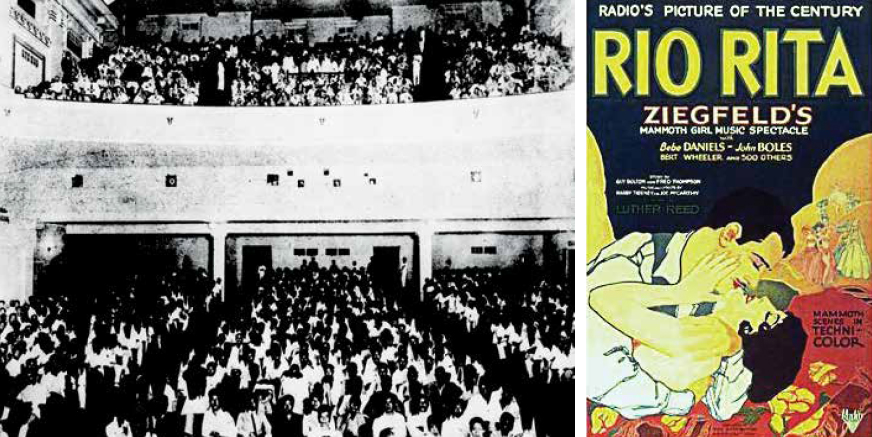

Crowds thronged to watch the musical comedy Rio Rita on opening night on 22 May 1930. The 1929 film, which starred American artistes Bebe Daniels and John Boles, was RKO Radio Pictures’ top-grossing box office hit of the time, featuring the latest in technicolour and sound. A journalist was so thrilled by the magnificence of the Capitol that he reported it as “almost too elaborate for a mere cinema” in the newspaper the next day.3

(Left) The crowd at the Capitol Theatre on opening night on 22 May 1930. The Europeans were formally dressed and seated on the balcony, while the locals mostly occupied the stalls. The photo also shows the projection room below the balcony. Malayan Saturday Post, 31 May 1930, p. 38.

(Left) The crowd at the Capitol Theatre on opening night on 22 May 1930. The Europeans were formally dressed and seated on the balcony, while the locals mostly occupied the stalls. The photo also shows the projection room below the balcony. Malayan Saturday Post, 31 May 1930, p. 38.(Right) Crowds thronged to watch the musical comedy, Rio Rita, at Capitol Theatre’s opening night on 22 May 1930. The 1929 film starred American artistes Bebe Daniels and John Boles, and was RKO Radio Pictures’ top-grossing box office hit, featuring the latest in technicolour and sound. The film was based on the 1927 stage musical produced by Florenz Ziegfeld. Image source: Wikipedia Commons.

Ticket bookings at the Capitol could be made by telephone. Subsequently, reservations for permanent seats each week for future screenings could also be booked in advance if requests were made in writing to the manager. Tickets were priced at $2 for circle seats and $1 for stalls; children were charged half price.

The European patrons, decked out in hats and jackets, would book the more expensive circle seats upstairs, while locals, who tended to dress less formally, would occupy the cheaper stalls.4 The theatre was touted by some as a place that allowed for the mingling of people, regardless of class and race, but in actual fact the haves and have-nots were separated physically by the price of a ticket.

Memories of the Capitol

Behind the grandeur and opulence, however, was back-breaking work. Wee Teck Guan, a former employee of Capitol Theatre, supplied cleaning services during the opening period. Supervising between 10 and 50 people on the job at any one time, Wee was responsible for making sure that the labour force was on site 24 hours a day.5

Wee continued working for the Capitol until the Japanese Occupation, when his job evolved into advertising. He employed rather unique approaches to publicise the screenings; for example, for the film The Jungle Princess, shown at the theatre in April 1937, Wee used a live model wearing a sarong in his publicity stunt.

Myra Cresson, a Singaporean of French-Portuguese descent who was a regular patron of the cinema in those early years, recalled that hats and tuxedos were the norm for the European community at Saturday evening shows, even with no air-conditioning in the theatre. After the show, the Europeans would invariably proceed to the original Satay Club at Hoi How Road, a narrow street just off Beach Road where the Alhambra cinema was located.6 According to Willis’s Singapore Guide, “After the cinema or when hotels are closed, it [was] not an uncommon sight to see European ladies and gentlemen in evening dress sitting around these ‘Satai’ stalls on the open road.”7

THE FILM-MAD FISHER BROTHERS

The South African brothers Joe and Julius Fisher were responsible for steering Capitol Theatre through its initial growth years. They had been mentored by their father, A.M. Fisher, a pioneer of early cinema in South Africa. The senior Fisher is credited for screening South Africa’s first film in 1898 (a feature of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession). He also made an early attempt at “air-conditioning” in 1906 by using a large fan blowing across ice in the show tent, and presenting South Africa’s first talkie by playing records simultaneously on a gramophone that was synchronised with the action on screen.8

The Fisher brothers first came to Singapore in 1918 as representatives of I.W. Schlesinger, an American immigrant to South Africa who became a prolific film producer as well as film distributor. The Fishers were not only involved in film but also handled “theatrical troupes for tours through Malaya and the Far East”.9 Joe Fisher later became general manager of Middle East Films before establishing Singapore First National Pictures Ltd in 1926.10

The Fishers were experienced in the film industry and well-connected with Hollywood producers by the time Capitol Theatre opened in 1930. They set up the Mickey Mouse Club and brought in the famed Marcus show to pull in the crowds to the Capitol. By 1940, after a decade with Capitol, the Fisher brothers finally took sole control of the theatre under their own company, Fishers Ltd.

The brothers financed a massive renovation programme of the Capitol in January 1940. This included installing air-conditioning as well as an electric substation to serve the needs of both theatre patrons and residents of Namazie Mansions, along with reupholstered seats that were laid in a staggered fashion, “thus obviating irritating head and body manoeuvres which were formerly necessary in order to gain a clear view of the screen”.11 The renovations were carried out by some 200 men who worked non-stop even when performances were underway.12

The theatre was such an attraction that people from the Malay Peninsula travelled south to see this marvel in engineering. Dr Maurice Baker, one of Singapore’s first-generation diplomats, was a student in Standard Seven in Ipoh when he was taken on his first visit to Singapore by his geography teacher. One of the highlights of his trip was to see the magnificent dome of the Capitol Theatre.13

Unfortunately, Capitol Theatres Ltd suffered a double whammy when Namazie died of a sudden heart attack at the age of 67 in July 1931, and the Great Depression and subsequent rubber slump of the 1930s took a toll on its business. The company underwent voluntary liquidation, and the management companies of the Capitol, Alhambra, Marlborough and Royal theatres merged to form Amalgamated Theatres by late 1939 with previous directors of the Capitol, including Joe Fisher, still part of the Board of Directors in the new company.14 Thankfully, Singapore was not completely devastated by the economic downturn15 and, defying all logic, saw a boom in the entertainment industry during this period.16

Live Performances at the Capitol

In the era of silent movies, music was key in creating atmosphere and portraying the emotions of the characters. The screening of a movie would be accompanied by a band playing live music. Even after talkies came on the scene, music was still integral to the storytelling.

Musician Paul Abisheganaden was entralled by the musical interludes played between the screening of movies. He quipped, “You went to the cinema not only to see the films but also to enjoy the music that took place at interval. And you would cut short your refreshments quickly to get back to your seat in order to be able to listen to… the musicians….”17 Before the days of jazz and pop, bands would play light orchestral pieces or salon music such as Albert W. Ketelbey’s In a Monastery Garden and In a Persian Market. The wages were so lucrative that many musicians from Goa and Manila came to Singapore to work.

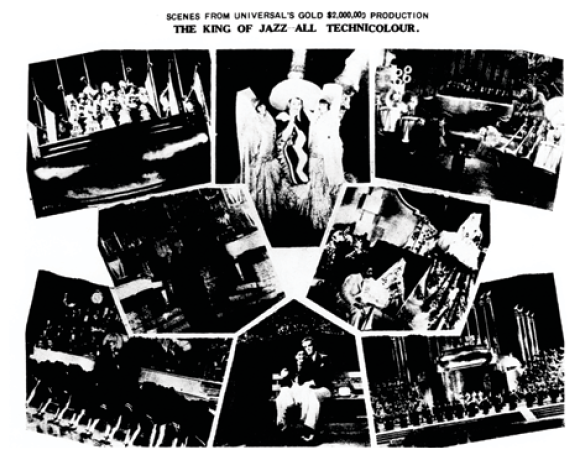

Scenes from Universal’s The King of Jazz production which was staged at Capitol Theatre. Malayan Saturday Post, 18 October 1930, p. 16.

Scenes from Universal’s The King of Jazz production which was staged at Capitol Theatre. Malayan Saturday Post, 18 October 1930, p. 16.Teo Moh Tet, whose father Teo Eng Hock was a well-known rubber planter, lived in a five-storey building beside Capitol’s huge carpark. She had the privilege of catching the A.B. Marcus Show when it was first staged at the Capitol Theatre in August 1934. The vaudeville production, which featured 45 skimpily clad girls on stage, had gained worldwide popularity when it first premiered in 1918. Although entertaining, it must not have been an appropriate show for a young girl.

Growing Up with the Capitol

Parents in the 1930s did not usually indulge their young children by taking them out to the cinema, especially if they were girls. A visit to the theatre was therefore an extraordinary affair to be remembered. Teo Moh Tet, who was about 10 or 11 in the 1930s, remembered being accompanied by her mother to the first colour film at the Capitol, likely Rio Rita, which was the opening night film when the theatre was launched on 22 May 1930.18 Interestingly, such early films were often productions of live stage performances.

As a girl growing up in Johor in the early 1930s, Hedwig Anuar, who became director of the National Library in 1965, recalled outings to cinemas as boisterous affairs: “There would be boys sitting in the row behind us kicking our seats… And all of us would be eating kachang puteh.”19 The atmosphere may have been more sedate at the glamorous Capitol but the film genres were the same. It was a time when musicals and dance were popular. Children learnt to sing the songs of the adorable child star Shirley Temple and were fascinated with the nimble dance moves of Hollywood greats like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

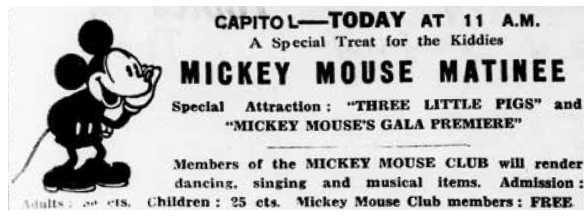

To attract the younger generation to the Capitol, Amalgamated Theatres established a branch of the Mickey Mouse Club in December 1932. The inaugural meeting attracted 200 members. The club, for children under 14, soon developed its own suite of programmes that included sports events, performances and charity work. The club elected its own Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse chiefs and by March 1933, had its own newspaper column, the Mickey Mouse Club Corner, in The Malaya Tribune.

Members of the Mickey Mouse Cub would meet on Saturday mornings before heading to the Capitol Theatre for the matinee screening of Mickey Mouse cartoons. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 Oct 1933, p. 7.

Members of the Mickey Mouse Cub would meet on Saturday mornings before heading to the Capitol Theatre for the matinee screening of Mickey Mouse cartoons. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 Oct 1933, p. 7.A monthly membership fee of 25 cents allowed two free shows a month at the Capitol, Alhambra or Pavilion cinemas20. Club members would meet on Saturday mornings before heading to the Capitol for the matinee screening of Mickey Mouse cartoons. Chan Keong Poh, who was about 14 years old then, recalled that Saturday morning meetings were held in the homes of the club organisers living at Namazie Mansions.21 Khatijun Nissa Siraj, who later became a women’s rights activist, noted that club members “all had Mickey Mouse badge[s]… Sometimes there were children’s functions after the movies… [which included] a mix of Europeans, Chinese, Indians who [belonged] to the club”.22

The area around the Capitol Theatre was home to more than a handful of English schools with teenagers hungry for new entertainment. Raffles Institution, Raffles Girls’ School, St Joseph’s Institution and Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus were just a few within a stone’s throw away.

The Capitol also appealed to the younger set as it featured more current, action-packed films. The 3.15pm matinee at the Capitol was especially popular with students as these afternoon screenings were cheaper than evening shows. Long queues for the matinees were not an uncommon sight. Lines would also form for the kachang puteh man hawking a variety of flavoured nuts along with vendors selling various snacks and candies, both before screenings and during interval time.23

In some schools, teachers occasionally rewarded students with cash for achieving good grades, and this was often used to purchase theatre tickets. Dr Tham Cheok Fai, later known as the father of neurosurgery in Singapore, recalled his math teacher challenging students with difficult arithmetic problems. Often, he would be the first to solve a question, and would use the 50-cent reward to catch a film at the Capitol. Tham said that 50 cents could purchase “two cinema shows in those days… [as] the seat in front… cost only 25 cents…”. This was normally a month’s worth of pocket money that would otherwise have been used for meals and transport.24

Blind activist and advocate for the disabled Ronald Chandran-Dudley recalled indulging in movie marathon weekends when he still had his sight as a teenager. He skipped Latin classes for the early morning show at the Alhambra, continued with the 11am show at Capitol, followed by the 1.30pm screening at Cathay and ended the marathon with the 4pm show before reaching home at 6pm.25

Residents of the Capitol

The apartments of Namazie Mansions fronting North Bridge Road commanded a panoramic view of St Andrew’s Cathedral and the Esplanade area. The residents included teachers of nearby schools as well as distinguished and well-heeled members of society.

Hilary Vivian Hogan, who was recognised for his contributions to Singapore’s cooperative movement, lived at the apartments when his family moved to Singapore around 1932, after his father had retired from working at Shell Petroleum in Samboe, Indonesia. As the Capitol was so ideally located, Hogan remembered walking everywhere: to his school, St Joseph’s Institution, to church, and in the evenings to the Esplanade to enjoy the breeze.26

Kartar Singh too had first-hand experience of growing up at the Capitol although he lived at the other end of the economic spectrum. His father had supplied girders for the construction of the theatre. When Kartar’s mother died suddenly, his father was unable to juggle work with the needs of his young family. Fortunately, his father found employment at the Capitol as the resident jaga, or night watchman, and moved the family into the theatre grounds.

The ticketing counter in the lobby of Capitol Theatre, 1982. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved, Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.

The ticketing counter in the lobby of Capitol Theatre, 1982. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved, Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.Kartar’s father was given a small room and a storage larder, but it was not a home by any means. The room could not accommodate the entire family of several siblings so once patrons cleared out of the theatre after the last show, they would pull out their charpoy (Indian roped beds) into the lobby to sleep. By 6 the next morning, these had to be packed away.

Kartar’s father set himself a strict timetable. He would wake up at 5am, get the cooking fire going, run to Hock Lam Street to buy groceries, then cook breakfast and pack lunch for the children as they got ready for school. He would then send them to school just before his work started at 9am. Kartar was then a student at nearby Raffles Institution. Due to his circumstances, he led an austere life at the Capitol, cooking by the roadside and studying under the street lamp.27

Occupied Capitol

During the Japanese Occupation, the building’s residents included Japanese military officers as well as Japanese proprietors of businesses that operated on the ground floor.

Kartar’s family continued to live at the Capitol during the Japanese invasion in February 1942. Films were still screened in the months before the fall of Singapore to raise the morale of the people, but eventually the British requisitioned the theatre and turned it into a food depot. The last film prior to Singapore’s fall was screened at 11pm on 19 December 1941.28 Kartar remembered that some seats were removed as sacks of flour were hauled in while the in-house restaurant, Blue Room, was converted into a canteen for the Air Raid Precaution Defence Forces.29

Maurice Baker recalled that when the Japanese invaded Singapore and took over the theatre, he and some friends had sneaked in knowing that it was stocked with food. “… [w]e just picked up a whole case of sardines. I carried it and we walked past the sentry. Normally, looters were shot and executed. We didn’t know we were looting. We just carried it past, grinned and bowed to the sentry and took it home… We lived on those sardines for quite a while.”30

During the Japanese Occupation, Capitol Theatre was renamed Kyoei Gekijo. Only films that had been vetted by the Japanese could be screened, along with theatrical performances. Patrick Hardie, a Eurasian interviewee, remembered that such performances included Japanese classical music performed by a Japanese orchestra as well as Japanese folk dances.31

In December 1944, towards the end of the Occupation, a loud explosion rocked the theatre. Kartar, who had by then married and moved to Henderson Road, heard the explosion as it resonated across town. Cycling to the Capitol as fast as he could, he witnessed the devastation: the theatre frontage had collapsed at the spot where his father would have been sleeping. He found his younger brother, his head in a pool of blood. His father and another brother had been taken to Raffles Girls’ school along with some others who were also injured.

In 2007, Capitol Theatre, Capitol Building, Capitol Centre and Stamford House were gazetted for conservation. Following redevelopment and refurbishment, Capitol Theatre officially reopened on 22 May 2015, exactly 85 years to the day when it first opened. Image source: VisitSingapore.com.

In 2007, Capitol Theatre, Capitol Building, Capitol Centre and Stamford House were gazetted for conservation. Following redevelopment and refurbishment, Capitol Theatre officially reopened on 22 May 2015, exactly 85 years to the day when it first opened. Image source: VisitSingapore.com.Kartar ran to the nearby Indian Tamil League Headquarters at Waterloo Street where his cousin was the secretary and one of the privileged few given a car by the Japanese. Using the borrowed vehicle, Kartar drove his family to the Kandang Kerbau Hospital, which then served as a civil hospital. His father was later detained by the Japanese, who suspected him of being involved in the sabotage and interrogated him for two hours. His father was eventually released as apparently some old films stored in an underground room had caught fire and ignited the gas tanks nearby, causing the explosion.32

When World War II ended in 1945, Shaw Organisation purchased Capitol Theatre and Namazie Mansions for $3.8 million, and renamed the latter Shaws Building, ushering in a new era for theatre and cinema in Singapore. After several decades as an iconic cinema in postcolonial Singapore, the theatre reopened in 2015, fully refurbished to reflect its former glory. It remains the only pre-war cinema in Singapore still in operation today.33

The author would like to thank Raphaël Millet, who reviewed this article before publication.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

NOTES

-

Choo, H. (Interviewer). (1982, June 30). Oral history interview with Haji Mohamed Javad Namazie [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000189/11/3, p. 22]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The Alhambra and Tivoli screened talkies prior to the Capitol but had to undergo some renovations to incorporate sound technology. See Talkie invasion. (1929, December 17). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Capitol Theatre. (1930, May 23). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Opening of Malaya’s premier picture palace The Capitol Theatre. Singapore. (1930, May 31). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 38. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, A.L.I. (Interviewer). (1986, November 6). Oral history interview with Wee Teck Guan [MP3 recording no. 000719/4/2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chiang, C. (Interviewer). (1985, August 20). Oral history interview with Myra Isabelle Cresson [MP3 recording no. 000594/12/2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Willis, A.C. (1936). Willis’s Singapore guide (p. 147). Singapore: Alfred Charles Willis. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Joe & Julius Fisher – Pioneers of Singapore entertainment. (1940, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 15; Streeter, L. (1940, January 28). From eye-killing flickers to modern marvels. The Sunday Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 31 Jan 1940, p. 15; Sundstrom, C. (2010, February). Almost 100 years old and still rolling! The history of SA cinema Part 2. Retrieved from Gauteng Film Commission South Africa website. ↩

-

Local and personal. (1922, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 8; S’pore cinema pioneer dies of heart attack in U.S. (1960, July 27). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Air-conditioned Capitol has 1,000 new seats. (1940, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Under your very nose a new theatre is built. (1940, January 21). The Sunday Tribune, p. 2; Capitol theatre to be air-conditioned. (1940, January 11). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1993, April 14). Oral history interview with Maurice Baker [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000095/6/1, p. 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Cinema merger details. (1932, November 29). Singapore Daily News, p. 1; Merger of local cinemas. (1932, November 29). The Straits Times, p. 12 ↩

-

With reference to Huff’s article that showed how Singapore managed to ride out the Depression. See Huff, W.G. (2001, May). Entitlements, destitution and emigration in the 1930s Singapore Great Depression. The Economic History Review, 54 (2), 290–323, pp. 290–291, 318–321; Loh, K.S. (2006, March). Beyond rubber prices: Negotiating the Great Depression in Singapore. South East Asia Research, 14 (1), 5–31, pp. 5-7, 30-31. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Van der Putten, J. (2010, February). Negotiating the Great Depression: The rise of popular culture and consumerism in early 1930s Malaya. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 41 (1), 21–45, pp. 21–23. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website ↩

-

Chua, C.H.J. (Interviewer). (1996, February 9). Oral history interview with Paul Abisheganaden [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001415/48/39, p, 468], Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1992, December 23). Oral history interview with Goh Heng Chong [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001392/2/2, pp. 13–14] Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, C.H.J. (Interviewer). (1998, July 21). Oral history interview with Hedwig Anuar Aroozo [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002036/44/2, p. 24]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

‘Shanghai Lass’. (1934, September 29). Mickey Mouse Club. The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeo, G.L. (Interviewer). (1987, July 27). Oral history interview with Chan Keong Poh [MP3 recording no. 000802/9/2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ruzita Zaki. (Interviewer). (1995, August 24. Oral history interview with Khatijun Nissan Siraj [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001663/36/5, p. 70]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Sng, S. (Interviewer). (2005, March 28). Oral history interview with Benjamin Khoo Beng Chuan [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002911/26/6, p. 127]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, L.C. (Interviewer). (1996, July 30). Oral history interview with Tham Cheok Fai [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001751/19/19, p. 2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Oral history interview with Benjamin Khoo Beng Chuan, 28 Mar 2005, p. 126. ↩

-

Low, M. (Interviewer). (2006, January 10). Oral history interview with Ronald Chandran Dudley [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003012/22/2, pp. 48–49]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, A. L. (Interviewer). (1997, February 26). Oral history interview with Hilary Vivian Hogan [MP3 recording no. 001778/33/1]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2002, July 19). Oral history interview with Kartar Singh [MP3 recording no. 002335/34/13]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

No more shows at Capitol Theatre. (1941, December 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Kartar Singh, 19 Jul 2002. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1993, April 14). Oral history interview with Maurice Baker [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000095/6/2, p. 19]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Tan, B. L. (Interviewer). (1985, April 17). Oral history interview with Patrick Hardie [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000545/9/5, p. 63]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2002, July 19). Oral history interview with Kartar Singh [MP3 recording no. 002335/34/6]; Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2002, July 26). Oral history interview with Kartar Singh [MP3 recording no. 002335/34/7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Tan, C. (2015, February 11). Singapura: The Musical to open at newly-refurbished Capitol Theatre in May. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website; Back in the spotlight. (2015, May 23). The Straits Times, p. 1; Khew, C., & Zaccheus, M. (2015, May 23). Nostalgia takes centre stage at iconic theatre. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩