May Singapore Flourish! Revisiting the Municipal Coat of Arms

In April 1948, the municipality of Singapore received a coat of arms by royal warrant. Mark Wong reports on the significance of this document.

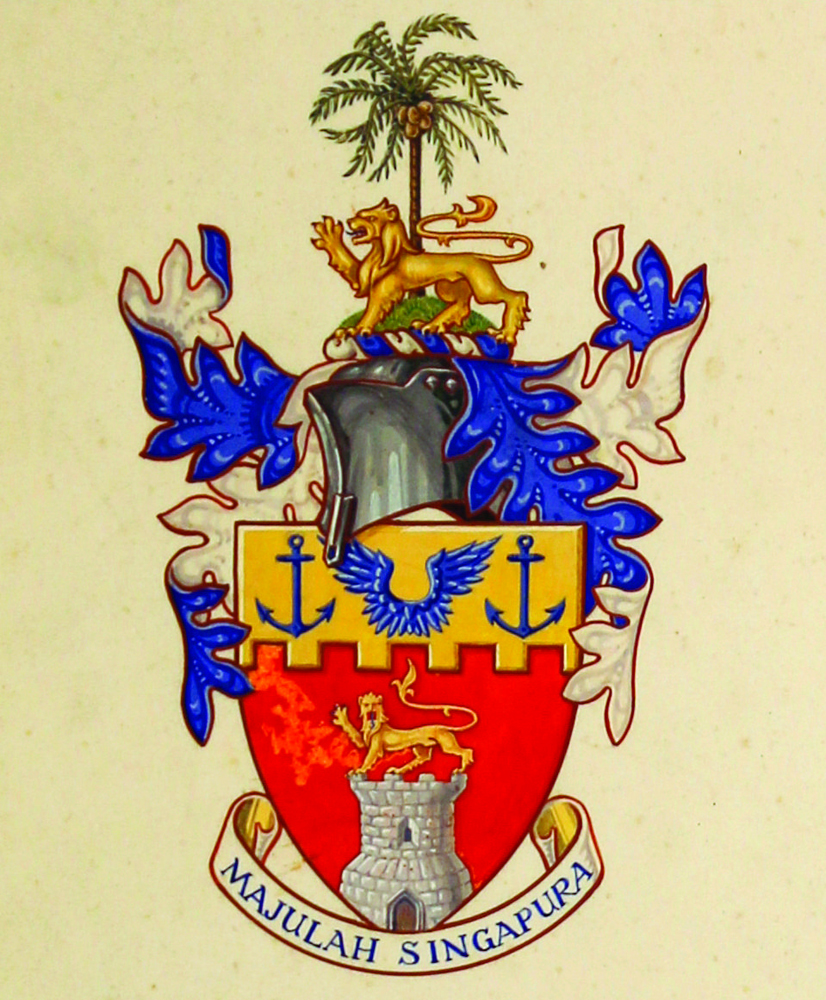

If you’ve ever been to Mount Emily Park1 and wondered about the colourful coat of arms mounted on the wall at the entrance, the answer to its identity lies in one of the documents on display at the exhibition, “Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents”.

The 1948 municipal coat of arms still features prominently today at the entrance of Mount Emily Park. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The 1948 municipal coat of arms still features prominently today at the entrance of Mount Emily Park. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Among the colonial-era documents at the exhibition held at the National Gallery Singapore is the Royal Warrant Assigning Armorial Ensigns for the City of Singapore – easily one of the most ornate of the items on display.

The Royal Warrant Assigning Armorial Ensigns for the City of Singapore, 9 April 1948. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Royal Warrant Assigning Armorial Ensigns for the City of Singapore, 9 April 1948. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Seen from the present perspective, the royal warrant – dated 9 April 1948 and almost 70 years old today – marks a transitional but significant period in Singapore’s history. A celebrated document in its day, the royal warrant represented a proud moment for a town that was still steeped in the hallowed symbols and practices of British colonial tradition, just three years after the end of the Japanese Occupation and resumption of British rule. But more importantly, the issue of the warrant also marked a watershed moment in Singapore’s eventful journey towards self-government and eventual independence.

The Royal Warrant

The royal warrant arrived in Singapore by ship in August 1948 “in a long red box, with G.R. VI embossed on it in gold”,2 a reference to King George VI, the British monarch who reigned from 1936 to 1952. The warrant was the result of an application made in July 1947 by the Singapore Municipal Commissioners to the College of Arms (College of Heralds), England, to register a coat of arms (armorial ensigns) for the Singapore Municipal Commission.3 The College of Arms and its functions still exist in the present day, and registering the design ensures that no other entity can use a similar design.

Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth as King and Queen of the United Kingdom, 12 May 1937. The royal warrant reached Singapore in August 1948 in a long red box bearing the initials of King George VI, the reigning British monarch. Sng Chong Hui Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth as King and Queen of the United Kingdom, 12 May 1937. The royal warrant reached Singapore in August 1948 in a long red box bearing the initials of King George VI, the reigning British monarch. Sng Chong Hui Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The warrant is written in fine copperplate calligraphy on parchment and measures 45 by 62 cm, inclusive of three elaborate seals attached at the base. The seals represent the three kings of arms, who are the senior officers of the College of Arms: specifically, the Garter King of Arms, Clarenceux King of Arms, and Norroy and Ulster King of Arms.

What is most visually striking about the warrant are the four coats of arms found on the top and left of the document. The three arms at the top represent the authorities granting the arms: in the centre lies the royal arms of the United Kingdom, flanked by the arms of the Earl Marshal of England (the Duke of Norfolk) on the left, and the arms of the College of Arms on the right.

The Municipal Coat of Arms

On the left of the document, significantly larger than the arms above it, is the new municipal coat of arms. A description of the arms can be found in the warrant, in the form of the official blazon:

“Gules a Tower issuant from the base proper on the battlements thereof a Lion passant guardant Or on a Chief embattled of the last a pair of Wings conjoined in base between two Anchors Azure And for the Crest On a Wreath Argent and Azure In front of a Palm tree fructed proper issuant from a Mount Vert a Lion passant Or.”

Written in the language of heraldry – an Anglicised version of Norman French – this translates into modern English as:

“A red shield, with a tower at the bottom. On the top of the tower, a golden lion walking, with one paw raised, looking to its left. Above the shield, with battlement effect, another panel of gold, with a pair of wings flanked by two blue anchors. The crest is a wreath of blue and silver leaves with another golden lion in front of a palm tree with coconuts on it, growing out of a green mound.”4

The images in the coat of arms are rich in symbolic meaning, some having been in public circulation for decades. The golden lion atop the tower previously represented Singapore on the coat of arms of the recently dissolved Straits Settlements.5 The pairs of wings and anchors highlight Singapore’s twin roles in international communications as seaport (since its founding in 1819) and as air hub (with the 1937 opening of Kallang Airport, one of the most modern in the world) at the time.

The crest of the Singapore municipality, consisting of a lion with a coconut palm behind it, appears at the top of the coat of arms. The municipal crest was well known to the people of Singapore as it was displayed in various locations around the town, including the pair of bronze plaques at Elgin Bridge, engraved by the Italian sculptor Rodolfo Nolli.

The Municipal Motto

What may surprise people are the words “Majulah Singapura” inscribed just below the shield. The Malay phrase is well known today as the title of Singapore’s national anthem and translated as “Onward Singapore”. The anthem was officially unveiled in December 1959 as one of three new state symbols in a newly self-governing Singapore. However, the appearance of the phrase on the 1948 royal warrant indicates a much longer history.

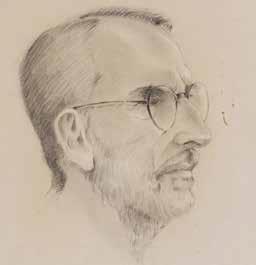

Portrait of Lazarus Rayman by William Haxworth. Rayman, as president of the Singapore Municipal Commission, was mentioned by name in the royal warrant. WRM Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Portrait of Lazarus Rayman by William Haxworth. Rayman, as president of the Singapore Municipal Commission, was mentioned by name in the royal warrant. WRM Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In fact, “Majulah Singapura” was the municipal motto of Singapore before World War II. According to an article in the 28 January 1940 edition of The Straits Times, the motto was originally written in English as “May Singapore Flourish”.

The English motto was translated into Malay as “Biar-lah Singapura Untong”, with the Malay version featuring on the official Municipal common seal. However, the words “biar-lah” (to let/allow) and “untong” (profit) were subsequently changed following a suggestion by the President of the Singapore Municipal Commissioners Lazarus Rayman, a Malay scholar. He felt that the word “untong” conveyed “mere commercial profit”, whereas “maju” expressed “the higher ideal of a continuous advancement commercially”. Besides, “maju” was “commonly used by Malay royalty whenever they pray for the prosperity of their country”.6

After World War II, “Majulah Singapura” grew in use and popularity. For example, the phrase was widely used in speeches and printed on decorative arches on City Day on 22 September 1951 in celebration of Singapore’s new status as a city of the British Commonwealth instead of a town. “Majulah Singapura” became a locus of budding patriotism amid a population that was becoming more politically conscious and emotionally attached to Singapore.

In 1952, Singapore City Councillor M.P.D. Nair even suggested that “instead of greeting each other with ‘hello,’ ‘good morning’ or good evening,’ people should say ‘Majulah Singapura’” instead. He felt that this would deepen their attachment to the city and “foster a new spirit”.7

Singapore’s use of a Malay motto provided inspiration to Penang, which similarly adopted an official motto in 1950. When the Penang Settlement Council had to decide between a Malay or English motto, council member K. Mohd. Ariff referred to Singapore’s choice of a Malay motto to sway the council: “It is Singapore’s motto that stimulated your committee to think, I hope, on right lines and at the same time pay a tribute to those far-sighted pioneers who coined ‘Majulah Singapura’ as the slogan for Singapore.”8 Penang eventually adopted the Malay motto “Bersatu dan Setia” (United and Loyal).

A HERALDIC GLOSSARY

Argent: Silver

Azure: Blue

Chief: Referring to the upper part of a heraldic device

Embattled: Having battlements

Fructed proper: Bearing correct fruit

Guardant: On guard

Gules: Red

Issuant: Coming from

Or: Gold

Passant: Passing or in motion

Mount vert: A green mount

The Singapore Municipal Commission

The royal warrant acknowledges the role of the Singapore Municipal Commission in applying for the new municipal coat of arms. The role and evolution of the Municipal Commission – created in 1887 to oversee local urban affairs such as water supply, electricity, gas, drains, roads and street lighting – was emblematic of Singapore’s journey towards self-governance. According to geographer Brenda Yeoh:

“The municipal authority was an integral part of the colonial power structure and served as an institution of control over the built environment of the colonial city. [The creation of the Municipal Commission] was both a response to the growing need for a more sophisticated machinery to run a burgeoning city as well as ‘a sort of compromise’ to satisfy local demands, largely articulated by the resident European population, for more control over local affairs.”9

While the composition and concerns of the Municipal Commission from the late 19th century tended to be European-centric and “hardly addressed the needs and aspirations of the Asian plebeian classes on their own terms”,10 this changed after World War II. “The British attached great importance on local government as a training ground for democracy and extended its scope in the post-war years.”11

In 1949, the Municipal Commission became the first public institution to be installed with a popularly elected majority when 18 out of the 27 commissioners were elected.12 This expanded local political participation in preparation for Singapore’s self-governance and subsequent independence. The Municipal Commission was renamed City Council in 1951 when Singapore attained city status.13

A COLONIAL TRADITION

Heraldry, which refers to the “system by which coats of arms and other armorial bearings are devised, described, and regulated”,14 has its origins in 12th-century Europe when designs on shields became a way by which medieval armies differentiated between friend and foe from a distance. Today, individuals, families, organisations, corporations and states can all apply for their own coat of arms. With its elaborate designs, symbols and meanings, the coat of arms is essentially a unique visual representation of one’s identity. Although a predominantly European practice, heraldic traditions are also found in Japan, where emblems or crests known as mon are used.15

Reflecting on an Unfamiliar Past

What is the significance of an obscure coat of arms from a bygone era in contemporary Singapore? The Royal Warrant Assigning Armorial Ensigns for the City of Singapore – with its archaic language, colonial symbols of authority and references to obsolete institutions such as the Singapore Municipal Commission – seems so distant from our lives today. By understanding its context and unpacking its meaning, however, we find in the royal warrant a record of a turning point in Singapore’s history.

Singapore in 1948 was poised to build its own self-determined future. But even as the first signs of political consciousness took root among the local populace, many of the foundations developed over a century of British rule remained – the rule of law, principles of urban planning, and the installation of certain forms of government and political institutions, among others. The social and political changes of the postwar years is best illustrated by the evolution in the meaning of the phrase Majulah Singapura – from the aspirational “May Singapore Flourish” of the municipal motto to the self-assured “Onward Singapore” of Singapore’s national anthem.

The royal warrant thus reveals Singapore in 1948 to be in a liminal zone, caught between the weight of colonial history and the promise of a new world.

The Royal Warrant Assigning Armorial Ensigns for the City of Singapore, along with other rare materials from the National Archives of Singapore and National Library, are on display at the permanent exhibition “Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents”. The exhibition takes place at the Chief Justice’s Chamber & Office, National Gallery Singapore.

Mark Wong is an Oral History Specialist at the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he conducts oral history interviews in areas such as education, the performing arts, the public service and the Japanese Occupation. He co-curated the exhibition, "Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents", now on at the National Gallery Singapore.

Mark Wong is an Oral History Specialist at the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he conducts oral history interviews in areas such as education, the performing arts, the public service and the Japanese Occupation. He co-curated the exhibition, "Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents", now on at the National Gallery Singapore.

NOTES

-

The park is the site of the former Mount Emily Swimming Complex, Singapore’s first public pool, which was converted from a service reservoir and opened in 1931. The reservoir was built in 1878 to supply the town with fresh water. ↩

-

The “R” in G. R. VI is an abbreviation of Rex (King). See New coat of arms arrives. (1948, August 15). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S’pore seeks coat of arms. (1947, July 30). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 15 Aug 1947, p. 5. ↩

-

The crest of the Straits Settlements arms came in four quadrants, each representing a constituent settlement – Singapore, Melaka, Penang and Labuan. The British dissolved the Straits Settlements on 1 April 1946, with Melaka and Penang joining the Malayan Union, and Singapore becoming a crown colony of its own. Labuan was incorporated into the crown colony of North Borneo on 15 July 1946. ↩

-

Word changed on Singapore’s common seal. (1940, January 28). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Say ‘Majulah Singapura’ he suggests. (1952, July 15). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Official motto for Penang adopted: ‘United and Loyal’. (1950, November 7). Singapore Standard, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeoh, B. S. A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment (p. 28). Singapore: University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO) ↩

-

Turnbull, C. M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (p. 269). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

McKerron, P. A. B. (1949). Colony of Singapore annual report, 1948 (p. 5). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SIN-[GBH]) ↩

-

The king sends congratulations. (1951, September 22). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oxford University Press. (2017). Heraldy. Retrieved from Oxford Dictionaries website. ↩

-

Slater. S. (2002). The complete book of heraldry: An international history of heraldry and its contemporary uses (p. 232). London: Lorenz. (Call no.: q929.6 SLA) ↩