When Tigers Used to Roam: Nature & Environment in Singapore

Urban development has destroyed much of the original landscape, as Goh Lee Kim tells us. But Singapore has taken great strides in conserving its natural heritage.

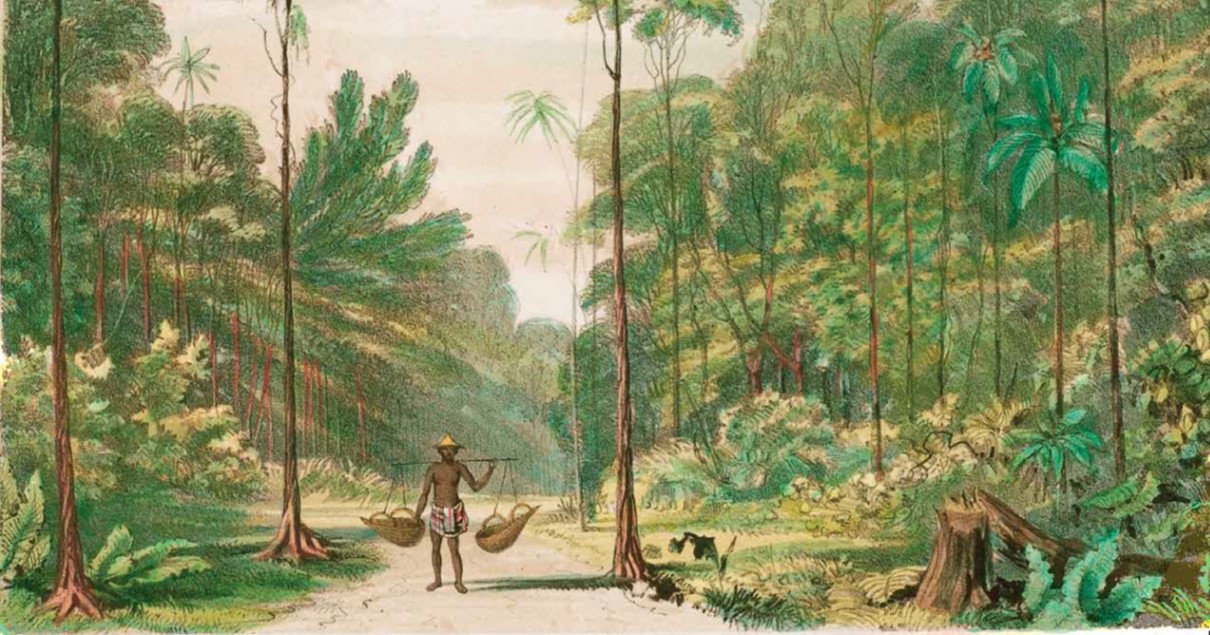

“View in the jungle, Singapore”, c.1845. A lithograph print showing a recently cleared stretch of jungle with a wide path cut through it. By the late 19th century, much of the primary forest in Singapore had been cleared for plantations and a growing migrant population. This print was originally published in Charles Ramsey Drinkwater Bethune’s View in the Eastern Archipelago: Borneo, Sarawak, Labuan, &c. &c. &c. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

“View in the jungle, Singapore”, c.1845. A lithograph print showing a recently cleared stretch of jungle with a wide path cut through it. By the late 19th century, much of the primary forest in Singapore had been cleared for plantations and a growing migrant population. This print was originally published in Charles Ramsey Drinkwater Bethune’s View in the Eastern Archipelago: Borneo, Sarawak, Labuan, &c. &c. &c. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Singapore was blanketed in lush green vegetation for centuries before Stamford Raffles arrived on the island in 1819. Primary tropical forest grew abundantly, interspersed with pockets of mangrove and freshwater swamps.1 The forest contained “an immense number” of species of trees, many of them scaling great heights.

The tropical vegetation enveloping the island likely supported a rich plethora of fauna, including tigers, although larger mammals commonly found in neighbouring lands, such as the elephant, rhinoceros and tapir, were not native to Singapore. A few hills dotted the island, with the highest, Bukit Timah, at the centre.2

Relatively untouched for centuries, the island’s landscape began to transform dramatically only after Singapore’s founding by Raffles. The Singapore River became the economic lifeline of the settlement following the establishment of the port and commercial centre along its banks. Development took place rapidly, and the population grew as it attracted immigrants from the Malay Archipelago, China, India, the Middle East, and even further afield from Europe and the Americas.

Destruction and Deforestation

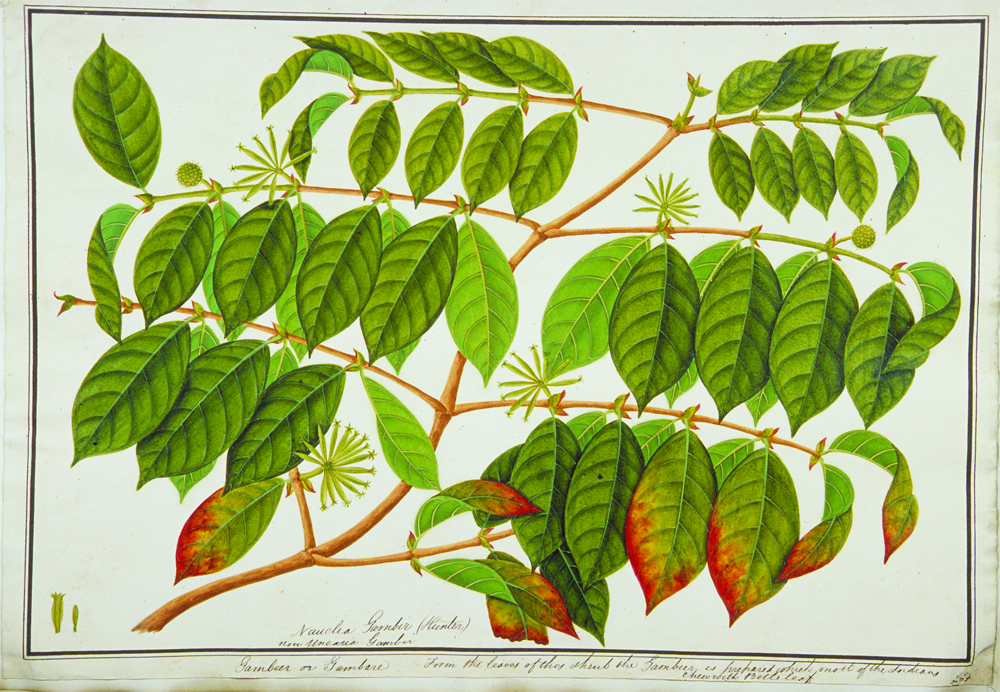

Along with the boom in trade, cultivation of cash crops for export also took off, spurred by the British who saw it as a means of raising capital. Gambier and pepper, which were usually planted together, proved to be the most economically viable crops in early 19th-century Singapore. Although gambier and pepper plantations had existed before the British arrived, their cultivation flourished only after 1836 due to an increasing demand for gambier by the dyeing and tanning industries. By the late 1840s, there were some 400 gambier and pepper plantations in Singapore.

Gambier (Nauclea gambir, Uncaria gambir) from the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings at the National Museum of Singapore. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Melaka. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Gambier (Nauclea gambir, Uncaria gambir) from the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings at the National Museum of Singapore. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Melaka. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Unfortunately, gambier cultivation had a detrimental effect on the primary forest. To obtain land for the plantations, the farmers, who were mostly Chinese, cleared large swathes of forest. To make matters worse, gambier plantations could only survive for 20 years at most as gambier rapidly exhausted the soil and rendered the land infertile for further cultivation. This resulted in further deforestation when the farmers abandoned the plantations and cleared new land to grow the crop.

The farmers also cut down large numbers of trees and used the wood as fuel to boil and process the harvested gambier. It was estimated that for every plot of land taken up by gambier plants, an equal area was logged for its processing.

At the same time, forests were cleared to make way for development and trees felled to provide residents with timber, fuel and charcoal. By the late 19th century, much of the primary forest was lost to indiscriminate deforestation. Once removed, primary vegetation is lost forever as it cannot regenerate on cleared land. Over time, much of the cleared land became overgrown with lalang, a weed that was very difficult to rid of. Already by 1859, it was reported that some 45,000 acres of land in Singapore had been abandoned.3

There was no attempt to control the rate of deforestation until the late 1870s, when the Colonial Secretary, Cecil Clementi Smith, tasked the Colonial Engineer and Surveyor-General, John F.A. McNair, to conduct a survey on the state of the timber forests in the Straits Settlements. McNair’s 1879 report described the dismal scene in Singapore: diminishing timber trees, indiscriminate deforestation, and an absence of legislation for forest protection.4 Despite McNair’s report, the colonial government did not take any action to protect the forest from further encroachment.

This situation remained until 1883 when a forest report commissioned by Governor Frederick A. Weld and put together by Nathaniel Cantley, Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens, again reported the “extensive deforestation” in Singapore and pointed out that “no sufficient attempts have been made to conserve the Government forest lands”.5 This time the government paid heed: based on Cantley’s recommendations, eight forest reserves, totalling about 8,000 acres, were carved up.

By 1886, most of Cantley’s recommendations had been implemented. A total of 12 reserves, comprising 11,554 acres, were demarcated: Blukang, Murai, Kranji, Selitar, Ang Mo Kio, Changi, Bukit Panjang, Military, Chan Chu Kang, Mandai, Sambawang, Bukit Timah, Pandan and Jurong.6 A Forest Department, managed by the Botanic Gardens, was established to take charge of the reserves and a Forest Police Force was hired. In a bid to reforest the reserves with economically valuable trees, nurseries were set up to grow saplings.

By the 1890s, however, the government decided to scale back its support for the forest reserves. The budget for the maintenance of forest reserves was trimmed as timber growth in the reserves was slow and failed to generate any substantial revenue. In January 1895, the control of the reserves was transferred from the Botanic Gardens to the Land Office, which neglected the reserves even further as they were deemed unprofitable.

Even with their protected status, the reserves suffered from further deforestation in the following decades. In 1901, for instance, part of the Bukit Timah reserve was cleared for water catchment, granite quarries and railway lines. The Forest Ordinance enacted in 1909 which made it an offence to “trespass, pasture cattle and cut, collect or remove any forest produce” from a reserve was not effective in preventing further exploitation.7

In 1914, land was cleared from Sembawang and Mandai reserves for military purposes, and in 1927, land from the Seletar, Changi, Pandan and Bukit Timah reserves were used for the cultivation of vegetables. Part of the Changi reserve was also sacrificed for the construction of a naval base.

The majority of the reserves did not survive this onslaught. The status of Bukit Timah as a forest reserve was revoked and reconstituted in 1930 so that it comprised only about 70 hectares of forested land for the purposes of “scenic beauty and botanical interests”. By 1936, Bukit Timah had become Singapore’s only forest reserve when the government decided to revoke all the other forest reserves, citing the afforestation efforts as “unjustifiable”.8

The outlook of forest reserves in Singapore improved in 1938 when control of the Bukit Timah reserve was given back to the Botanic Gardens to ensure its conservation. In the following year, mangrove forests at Kranji and Pandan were gazetted as forest reserves. All three were placed under the charge of the Director of the Botanic Gardens, who was designated as Conservator of Forests.

Unfortunately, Bukit Timah reserve suffered severe damage during the Japanese invasion of Singapore in February 1942. After landing in Singapore, the Japanese targeted the Bukit Timah area. The ensuing battle between invading Japanese forces and Allied troops left its toll on the reserve: trenches and caves were excavated, trees were felled, and mortar shells were strewn all over.

When the Japanese Occupation ended in 1945, Bukit Timah reserve became a concern once again as granite quarries in the area began encroaching on the reserve. In April 1950, the government appointed a Select Committee on Granite Quarries and Nature Reserves to study the impact that the quarries had on the reserve. Following the recommendations of the committee, the Nature Reserves Ordinance was passed by the Singapore Legislative Council in January 1951, gazetting Bukit Timah, Kranji, Pandan, Labrador and the Central Catchment area as nature reserves as well as prohibiting activities such as quarrying and the destruction of flora and fauna.9 Today, all national parks and nature reserves in Singapore are protected under the Parks and Trees Act.

The Protection of Fauna

Generations of human activity on the island have also wreaked disastrous consequences on the fauna. Continued deforestation ravaged the natural habitats of native fauna and threatened their survival. Hunting, both for sport and consumption, as well as the rampant animal trade in Singapore exacerbated the situation. As a result, species such as the tiger and clouded leopard vanished from Singapore, while others, such as the sambar deer and barking deer, dwindled in numbers.

Three European men on a hunting trip in the jungle posing with an object that could possibly be tiger skin, 1890s. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved, Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.

Three European men on a hunting trip in the jungle posing with an object that could possibly be tiger skin, 1890s. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved, Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.Wildlife protection gained a foothold in Singapore with the enactment of the first legislation for the protection of wild fauna in 1884 – the Wild Birds Protection Ordinance – which prohibited the unlawful killing and capture of selected species of wild birds as well as the possession and sale of their skins and plumage.10 This ordinance was enacted to curb the excessive hunting and capture of wild birds for sport and the bird trade.

In 1904, the Wild Birds Protection Ordinance was repealed and replaced by the Wild Animals and Birds Protection Ordinance. Apart from the continued protection of birds, the new legislation prohibited the killing and capture of wild animals.11 The legislation continued to be amended and updated with revised editions, and is known at present as the Wild Animals and Birds Act.

Hunters posing with their catch during an elephant hunt in Singapore in the 1900s. Sport hunting and the wildlife trade were factors that caused the rapid depletion of fauna in Singapore. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Hunters posing with their catch during an elephant hunt in Singapore in the 1900s. Sport hunting and the wildlife trade were factors that caused the rapid depletion of fauna in Singapore. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.TIGER HUNTS

The proliferation of gambier and pepper plantations in the 1830s was linked to a rise in tiger sightings and attacks. Having lost their natural source of prey and the protection of thick forest cover, tigers ventured into the plantations and attacked workers. The earliest mention of a tiger attack in local news appeared in the 8 September 1831 edition of the Singapore Chronicle, which reported that “tigers are beginning to infest the vicinity of the town, to such a degree as to require serious attention on the part of the local authorities”.12

The remains of a Chinese woodcutter, who had been missing for days, were discovered near the town centre by his friends. The tiger’s paw prints were still clearly visible around the area. Another person had been killed since the report, but in a different location.

Members of the Straits hunting party with the tiger they shot at Choa Chu Kang Village in October 1930. From left: Tan Tian Quee, Ong Kim Hong (the shooter) and Low Peng Hoe. Tan Tuan Khoon Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Members of the Straits hunting party with the tiger they shot at Choa Chu Kang Village in October 1930. From left: Tan Tian Quee, Ong Kim Hong (the shooter) and Low Peng Hoe. Tan Tuan Khoon Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Tiger attacks became more rampant in the mid-19th century, when gambier plantations, followed by rubber, rapidly expanded in Singapore. In response, the government offered rewards for the capture of tigers, which encouraged many to attempt to hunt and trap the predator. Tiger sightings had dropped drastically by the time the last wild tiger was shot in Singapore in 1930 in Choa Chu Kang Village; besides the success of hunts, the tiger population had shrunk because much of the land had become deforested and was overgrown with lalang.13

Water and Public Health

The Singapore River was critical to the growth and development of the island as a centre of trade and commerce for more than 150 years. From the onset of Singapore’s founding, the river bustled with activity as vessels transported cargo and goods to and from the docks. Godowns, shipyards, factories and living quarters occupied the banks of the river and its environs. The combination of heavy water traffic and rapid urban development along its banks soon led to the pollution of the river.

An ink and sepia drawing titled “The River from Monkey Bridge” (1842–43) by Scotsman Charles Andrew Dyce who lived in Singapore in the 1840s. This is a scene of the Singapore River at Boat Quay from Monkey Bridge (where Elgin Bridge stands today). It shows the godowns along the river, coolies loading and unloading goods from the clipper ships. National University of Singapore Museum Collection, courtesy of NUS Museum.

An ink and sepia drawing titled “The River from Monkey Bridge” (1842–43) by Scotsman Charles Andrew Dyce who lived in Singapore in the 1840s. This is a scene of the Singapore River at Boat Quay from Monkey Bridge (where Elgin Bridge stands today). It shows the godowns along the river, coolies loading and unloading goods from the clipper ships. National University of Singapore Museum Collection, courtesy of NUS Museum.As early as 1822, a committee established by Raffles reported that a large amount of silt had built up around the mouth of the Singapore River due to the construction of jetties. This had caused navigation in the already shallow channel to become more difficult. When John Crawfurd was appointed as Resident in 1823, he highlighted the river’s significance to Singapore but pointed out that some form of dredging was “indispensable”.14

Several attempts were made by the government to dredge the river, but none succeeded in thoroughly clearing the sedimentation that continued to accumulate as development continued. The situation was not unique to the Singapore River; there were also reports of blockages at other waterways on the island, such as the Brass Bassa (Bras Basah) Canal.

By the 1840s, there was rising concern that the increasingly obstructed mouth of the Singapore River might cause disruptions to trade. The issue was highlighted by the Grand Jury to the Court in May 1848, recommending the removal of the obstruction because it threatened to become “seriously detrimental to the trade of the Port”.15 In April 1849, the Grand Jury revisited the issue once again, and pointed out that no action had been taken by the government. Although a dredge was eventually built in the mid-1850s, it could not function properly and was decommissioned in 1861.

Silt was not the only pollutant in the Singapore River. Garbage, industrial waste and sewage ended up in the river along with oil from the vessels plying the waters. The river swiftly deteriorated into a cesspool and constantly emitted a foul stench.

Interestingly, the waterways were so contaminated that they became a natural deterrant against malaria, a common disease in Singapore back then. The surgeon Dr Robert Little noticed that people living along Rochor Canal did not contract malaria despite the unhygienic living conditions. After examining the canal’s waters in 1847, he concluded that the sulphuretted hydrogen gas, from which the foul smell of the polluted waters originated, was responsible for killing malarial germs in the area.16

Notwithstanding Dr Little’s theory, the polluted waters of Singapore River and other waterways became a source of infectious diseases and a threat to public health. In his 1886 report, Dr Gilmore Ellis, the Acting Health Officer, linked the prevalence of diarrhoea and cholera to “excremental filth poisoning”17 arising from the lack of a catchment system in the settlement and the ensuing accumulation and putrefaction of sewage in the river. He stressed the importance of having a sewerage system to properly dispose of waste matter. In 1892, the Municipal Health Officer, Dr C.E. Dumbleton, recommended that strong measures be taken to curb the pollution of the river.

Over the next decades, various committees, such as the Singapore River Commission in 1898 and the Singapore River Working Party in 1954, were formed to look into the pollution of the Singapore River, and each made recommendations on how the river could be cleaned up. However, most of the recommendations were never implemented due to the high costs of the work required. Dredging continued and was done regularly, but it was not effective since it could not prevent silting nor act as a deterrent to the dumping of waste into the water. Pollution continued to plague the river right up to the mid-20th century.

Post-independence Initiatives

Between the 1960s and 80s, Singapore became rapidly industrialised, with numerous factories and manufacturing plants opening across the island. This gave rise to another environmental challenge: air pollution. The situation was especially dire in Jurong where the large concentration of factories there emitted pollutants such as dust, soot, carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide into the air.

To tackle the problem, the government formed the Anti-Pollution Unit in 1970. Tracking centres were set up across the island to monitor the amount of pollutants in the air, and efforts were made to relocate pollutive industries, such as sawmills and plywood factories, away from residential areas. New industries also needed permission from the Anti-Pollution Unit before they could open factories in Singapore. In 1971, the Clean Air Act came into force to control and regulate emissions from trade and industrial premises.

The government also implemented various initiatives and programmes to improve the environment and the standard of living. One of the first was the Garden City plan in 1967, which aimed to transform Singapore into a clean and green city. In subsequent years, thousands of trees and shrubs were planted throughout the island, including in built-up areas and along roads. In 1972, the Ministry of Environment was formed for the express task of creating a clean environment for the people. Singapore was one of the first few countries at the time with a ministry dedicated to environmental matters.

In 1977, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew ordered a clean-up of all rivers in Singapore. It was a massive programme, beginning with the removal of sources of pollution from the Singapore River and Kallang Basin. Squatters were resettled, industries, businesses and street hawkers were relocated, and pig and duck farms were phased out. Within 10 years, the Singapore River was transformed from a toxic river devoid of marine life to a clean body of water that was capable of supporting fish and prawns.

A relatively pristine Singapore River in 1983 with shophouses in the distance and the odd sampan traversing its length. Unbridled boat traffic and squatter colonies along its banks had led to heavy pollution of the river until 1977 when then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew ordered a major clean-up of all rivers in Singapore. All rights reserved, Kouo Shang-Wei Collection, National Library Board, Singapore.

A relatively pristine Singapore River in 1983 with shophouses in the distance and the odd sampan traversing its length. Unbridled boat traffic and squatter colonies along its banks had led to heavy pollution of the river until 1977 when then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew ordered a major clean-up of all rivers in Singapore. All rights reserved, Kouo Shang-Wei Collection, National Library Board, Singapore.In subsequent decades, the government continued with its efforts to ensure the protection and sustainability of Singapore’s environment and biodiversity. On the environmental front, the Singapore Green Plan – a blueprint to turn Singapore into a green city by 2000 – was presented at the Earth Summit in Brazil in 1992. It was updated in 2002 with the Singapore Green Plan 2012 and eventually replaced by the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015, which mapped out future plans and strategies to create a more sustainable environment.

To conserve biodiversity, Singapore became a signatory of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) treaty in 1986, pledging to regulate the trade in endangered wildlife and wildlife products. In 1992, Singapore signed the Convention on Biological Diversity along with 152 other countries to reaffirm its stand on the protection of animal and plant life.

Pulau Ubin, with the clouds reflected in its abandoned quarry, is a scene that is rare in urban Singapore today. Photo by Richard W.J. Koh.

Pulau Ubin, with the clouds reflected in its abandoned quarry, is a scene that is rare in urban Singapore today. Photo by Richard W.J. Koh.Biodiversity conservation was strengthened in 2009 with the National Park Board’s Conserving our Biodiversity strategy and action plan. In 2015, the Nature Conservation Masterplan was launched, charting the course of Singapore’s biodiversity conservation plans for the next five years.

These moves may seem like a little too late given that Singapore has already lost nearly 73 percent of its plant and animal species over the last 200 years. Being an island with precious few resources, Singapore has always struggled to balance the need for development with conservation. What is lost forever in terms of biodiversity cannot be replaced, but Singapore has at least taken concrete steps towards the creation of a sustainable nature and environment for our future generations. Hopefully more will be done in the years ahead.

Goh Lee Kim is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the library’s business, and science and technology collections, developing content, and providing reference and research services.

Goh Lee Kim is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the library’s business, and science and technology collections, developing content, and providing reference and research services.

REFERENCES

Barnard, T.P. (Ed.). (2014). Nature contained: Environmental histories of Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 304.2095957 NAT)

Barnard, T.P. (2016). Conservation and forests. In Nature’s colony: Empire, nation and environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 580.735957 BAR)

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC)

Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore River: A social history, 1819–2002. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOB-[HIS])

Fewer timber thefts at Bukit Timah reserve. (1939, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Local. (1850, March 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Prof Koh: Earth Summit was a breakthrough. (1992, June 20). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

River pollution in Singapore. (1896, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sharp, I., & Lum, S. (Eds.). (1996). Where tigers roamed. In A view from the summit: The story of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University and the National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 333.78095957 VIE)

Singapore forests: Gradual invasion of the reserves. (1928, July 19). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore. Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources and Ministry of National Development. (2014). Our home, our environment, our future: Sustainable Singapore blueprint 2015. Retrieved from Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources website.

Singapore. National Parks Board. (2009). Conserving our biodiversity: Singapore’s national biodiversity strategy and action plan. Retrieved from National Parks Board website.

S’pore to become beautiful, clean city within three years. (1967, May 12). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Smog law plea to Lee. (1970, August 1). The Singapore Herald, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

S. S. forest administration. (1916, November 25). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, A. (2015, June 28). New blueprint to conserve S’pore’s marine heritage. The Straits Times, pp. 2-3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, Y.S., Lee, T.J., & Tan, K. (2009). Clean, green and blue: Singapore’ journey towards environmental and water sustainability. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 363.70095957 TAN)

Tan, S.T.L., et al. (2011). Battle for Singapore: Fall of the impregnable fortress (p. 236). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 940.5425957 TAN)

Tortajada, C., Joshi, Y.K., & Biswas, A.K. (2013). The Singapore water story: Sustainable development in an urban city-state. New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 363.61095957 TOR)

Turnbull, C. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.97 TUR)]

NOTES

-

Yee, A.T.K., et al. (2011). The vegetation of Singapore – an updated map. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore, 63 (1 & 2), 205–212, p. 205. Retrieved from Singapore Botanic Gardens website. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1971). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian Islands and adjacent countries (pp. 395–403). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, New York. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.8 CRA) ↩

-

The timber trees of the Straits Settlements. (1881, April 18). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

McNair, J.F.A. (1879, October 3). Report by the Colonial Engineer on the timber forests in the Malayan Peninsula. In Straits Settlements Government Gazette (pp. 893–903). Singapore: Mission Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SCG; Microfilm no.: NL 1008) ↩

-

Cantley, N. (1885). Report on the forests of the Straits Settlements. In Annual report on the Botanic Gardens, Singapore, for the year 1879–1890. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Cantley, N. (1887, April 7). Annual report on the Forest Department, Straits Settlements, for the year 1886. In Straits Settlements Government Gazette (pp. 512–518). Singapore: Mission Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SCG; Microfilm no.: NL1017) ↩

-

Straits Settlement. The Laws of the Straits Settlements, Vol III, 1908–1912. (1926, Rev. ed.). Forest Ordinance (1909, October 1). (No. 108, section 25, p. 24). Retrieved from the National University of Singapore website. ↩

-

Forest reserves to go. (1937, April 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nature reserves for Singapore. (1951, January 12). Singapore Standard, p. 2; Indigenous Singapore. (1951, February 3). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1884, June 13). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (pp. 695–696). Singapore: Mission Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SCG; Microfilm no.: NL1013) ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1904, November 18). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (pp. 2565–2567). Singapore: Mission Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SCG; Microfilm no.: NL 1054) ↩

-

Untitled. (1831, September 8). The Singapore Chronicle, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A tiger visits Singapore. (1930, November 8). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 38. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2, p. 39). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Untitled. (1848, May 13). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Rochore canal smell killed malaria – he found in 1847. (1959, October 31). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Insanitary Singapore. (1889, December 17). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩