Women on a Mission

Female missionaries in colonial Singapore have made their mark in areas such as education, welfare and health services. Jaime Koh looks at some of these intrepid trailblazers.

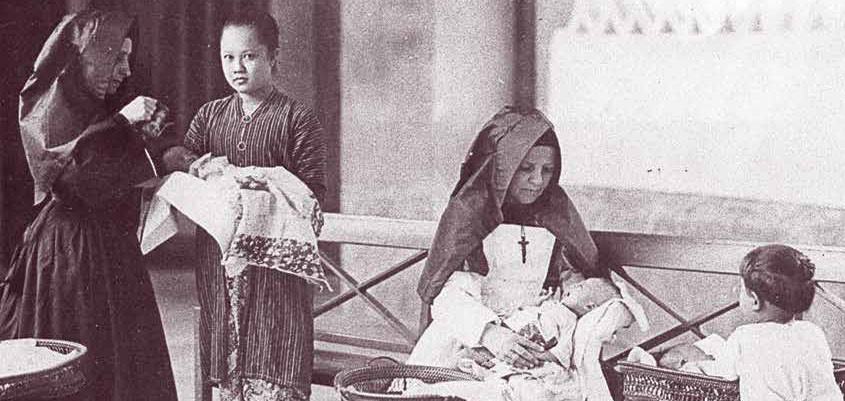

The Catholic sisters of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus with some orphans and their Malay nanny in 1924. In addition to a school, the convent also ran an orphanage that accepted and cared for orphans and abandoned babies. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Catholic sisters of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus with some orphans and their Malay nanny in 1924. In addition to a school, the convent also ran an orphanage that accepted and cared for orphans and abandoned babies. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Nineteenth-century Singapore was a thriving centre of commerce that held much promise. Soon after the British established a trading post in 1819, Singapore’s status as a free port and great emporium grew, attracting many who were drawn to the economic opportunities the island offered. Besides workers and merchants, the settlement also attracted Christian missionaries from the West who saw an opportunity to spread their message “among heathen and other unenlightened nations”1 in Asia.

As early as 1820, missionary societies of various denominations began to dispatch their representatives to sow the seeds of the Christian faith in Singapore. The Protestants were among the earliest to arrive, establishing churches and printing presses, and evangelising through preaching on the streets and home visits. Over time, the Protestant missionaries started schools and provided medical and social services for the poor and the displaced. Catholic missionaries followed, and similarly established churches and schools in Singapore.

Most of the early missionaries who came were men. In the early 19th century, the few women who ventured to Asia were the wives, sisters or relatives of Protestant missionaries who supported the men in their work abroad.2

Male missionaries were encouraged to bring their wives with them for several reasons. The first was the perception that missionaries who came with their families were better received in foreign lands as they gave the impression of coming with “peaceful intent”. The second was that missionary wives were seen as models of solicitous female behavior, thus demonstrating the virtues of good Christian families.3

Conversely, mission groups were initially reluctant to send unmarried female missionaries abroad. It was feared that they would either get married, or, being of weaker disposition, would not be able to cope with the rigours of living in a strange land and liable to suffer a nervous breakdown. The belief at the time was that women were “more emotional and less controlled, more anxious minded, more easily ‘worried’, more given to overtax their strength… more depressed by heathenism”.4

Things began to change from the 1850s onwards when missionary societies started to actively recruit and send unmarried female missionaries overseas. This was a result of a growing need for specialised services in education and medical work as well as increasing calls in Western society and within the church there to give women a more prominent role in mission work.5

Singapore in the 19th century was clearly a male-dominated society, with men outnumbering women by as many as four to one.6 There is no known data on the number of children before 1871 when the first of a series of regular census was taken. The population censuses of 1871, 1881 and 1891 put the number of children (under the age of 15) as 18.1 percent, 16.4 percent and 14.3 percent of the total population respectively.7

There was little public demand for education and the Bengal government in Calcutta – the capital of British territory in India until 1911 – was unwilling or unable to channel any money into developing education, much less education for girls, in Singapore. Most people in Singapore at the time did not even think that girls needed to be educated. Likewise, social welfare services were very basic. In fact, social welfare and education provisions in 19th-century Singapore were considered “below even the rudimentary standards” expected of governments at the time.8

The first female missionaries sent to Singapore from the West were well positioned to fill these gaps, and many went on to make tremendous contributions to society. In several cases, their legacies persist to the present day in the form of schools and institutions they founded.

The London Missionary Society

The earliest female missionaries in Singapore were the wives of missionaries from the London Missionary Society (LMS), a Protestant society founded in London in 1795. One of the LMS’s most important contributions in Singapore, apart from the introduction of the printing press, was setting up schools.

Bessie Osborne, wife of a London Missionary Society (LMS) missionary William D. Osborne, who worked with the Indian leper community in Trivandrum, India, c. 1900−1910. LMS, founded in 1795 in London, is one of the earliest Christian missionary groups that went out to Asia to proselytise. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bessie Osborne, wife of a London Missionary Society (LMS) missionary William D. Osborne, who worked with the Indian leper community in Trivandrum, India, c. 1900−1910. LMS, founded in 1795 in London, is one of the earliest Christian missionary groups that went out to Asia to proselytise. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.Mrs Claudius Henry Thomsen, who accompanied her LMS missionary husband, Claudius Henry Thomsen, to Singapore, is credited for starting the first school for girls in 1822. Known as Malay Female School, it was designed chiefly as a day school for girls “of any class or denomination” where they were taught needlework, catechism, hymns and prayers, reading and writing in Malay, and arithmetic. Although the school had only six students, its establishment marked the beginning of formal education for girls in Singapore.9

The LMS missionaries went on to start several other schools here. In 1830, there was reportedly a school for Chinese girls under the care of a Miss Martin. Nine years later, in 1839, a boarding school for “girls of European fathers and Malay mothers” was established. It was run by Mrs A. Stronach and Mrs J. Stronach, wives of the Stronach brothers, Alexander and John, who were both LMS missionaries. The subjects taught included English and Malay languages, and hygiene. There are few surviving records of these schools beyond the dates when they were established. They were likely short-lived too and closed down when the LMS withdrew from Singapore in 1847.10

But one school started by the wife of an LMS missionary has survived until today. This was the Chinese Female Boarding School, established in 1842 by Mrs Maria Dyer (nee Tarn), wife of LMS missionary Reverend Samuel Dyer. Mrs Dyer had been in charge of several girls’ schools in Penang and Melaka in the 1820s and 1830s when the Dyers were posted there for missionary work. Mrs Dyer was prompted to start the school in Singapore when she moved here and encountered young girls being sold as slaves on the streets.11 The Chinese Female Boarding School began with 19 girls in a rented house in North Bridge Road, where they were given a basic education in English and homemaking skills.

Mrs Dyer’s association with the school ended in 1844 when she left Singapore after the death of her husband. The school was placed in the care of Miss A. Grant, a missionary from the Society for the Promotion of Female Education in the East (SPFEE; see text box below) who took over the running of the school.

Under Miss Grant, the school, which had been renamed Chinese Girls’ School, operated as an orphanage for unwanted girls as well as a boarding school.12 One of Miss Grant’s students was Yeo Choon Neo, the first wife of Song Hoot Kiam, the noted Peranakan community leader after whom Hoot Kiam Road is named.13

Sophia Cooke

After Miss Grant left Singapore in 1853, the SPFEE sent another missionary, Sophia Cooke, to run the school. Miss Cooke would manage the school for the next 42 years, and her name became synonymous with the institution − “Miss Cooke’s School”, as people would come to call it.14 By this time, the school had moved several times, from North Bridge Road to Beach Road, before settling down at 134 Sophia Road in 1861.

An undated portrait of Miss Sophia Cooke, a missionary from the Society for the Promotion of Female Education in the East (SPFEE). In 1853, Miss Cooke took over the management of Chinese Girls’ School – initially established as the Chinese Female Boarding School in 1842 – and would run it for the next 42 years. Her name became synonymous with the institution and came to be called “Miss Cooke’s School”. Image source: Walker, E. A. (1899). Sophia Cooke, or, Forty-Two Years’ Work in Singapore (frontispiece). London: E. Stock. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B29032405C; Microfilm no.: NL 11273).

An undated portrait of Miss Sophia Cooke, a missionary from the Society for the Promotion of Female Education in the East (SPFEE). In 1853, Miss Cooke took over the management of Chinese Girls’ School – initially established as the Chinese Female Boarding School in 1842 – and would run it for the next 42 years. Her name became synonymous with the institution and came to be called “Miss Cooke’s School”. Image source: Walker, E. A. (1899). Sophia Cooke, or, Forty-Two Years’ Work in Singapore (frontispiece). London: E. Stock. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B29032405C; Microfilm no.: NL 11273).In addition to running the girls’ school, Miss Cooke also started a Chinese “ragged school”15− a charitable establishment providing free education for poor children − that took in children as well as their mothers. Inspired by similar schools in London, the ragged school opened on 6 March 1865.16 Buoyed by its success, Miss Cook started a second such school but there are no records of what happened to these two ragged schools.

In 1900, the SPFEE was dissolved and the Chinese Girls’ School was taken over by the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society (CEZMS) and became known as the CEZMS School. In 1949, the school was renamed St Margaret’s School (after Queen Margaret of Scotland), and is today the oldest girls’ school in Singapore in existence.17

Students from the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society School or the CEZMS School playing netball at its premises in Sophia Road, c. early 1900. The school has changed names and moved locations several times since its founding in 1842 as the Chinese Female Boarding School. In 1949 it was renamed St Margaret’s School, after Queen Margaret of Scotland. Courtesy of St Margaret’s Secondary School.

Students from the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society School or the CEZMS School playing netball at its premises in Sophia Road, c. early 1900. The school has changed names and moved locations several times since its founding in 1842 as the Chinese Female Boarding School. In 1949 it was renamed St Margaret’s School, after Queen Margaret of Scotland. Courtesy of St Margaret’s Secondary School.A MATCH MADE IN SCHOOL

Over time, the Chinese Girls’ School gained a reputation for cultivating good Christian wives with practical domestic skills. Chinese men from China, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) who converted to Christianity would approach the school in search of a suitable bride. The girls were married off from as early as 13 or 14 years old; most of these arranged marriages were said to be successful as the suitors were carefully screened by the school. The arranged marriages took place so frequently that its founder Sophia Cooke was said to have bought a wedding dress to be kept as school property for loan to girls who were getting married. The school continued to play the role of matchmaker right up to the 1930s.18

Besides education, the indefatigable Miss Cooke also helped improve the welfare of women, sailors, policemen, soldiers and the sick. She visited women in their homes and hosted regular meetings for young girls and mothers as part of a social support group. During these meetings, the girls would pray and listen to Christian messages from young women missionaries, whom locals called the Bible women. In turn, the local women were taught English and skills such as sewing and cooking.19 By 1897, these meetings developed into a formal organisation that became known as the Singapore branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

Another group Miss Cooke worked with were police, sailors and soldiers. She held Bible classes for them as well as attended to the needs of destitute and sick sailors. In 1882, together with a Brethren missionary Mr Hocquard, Miss Cooke started the Sailors’ Rest to provide shelter and food for homeless sailors. The Sailors’ Rest became the Boustead Institute in 1892 – named after the English businessman and philanthropist Edward Boustead – and continued to look after the welfare of destitute sailors in Singapore.20

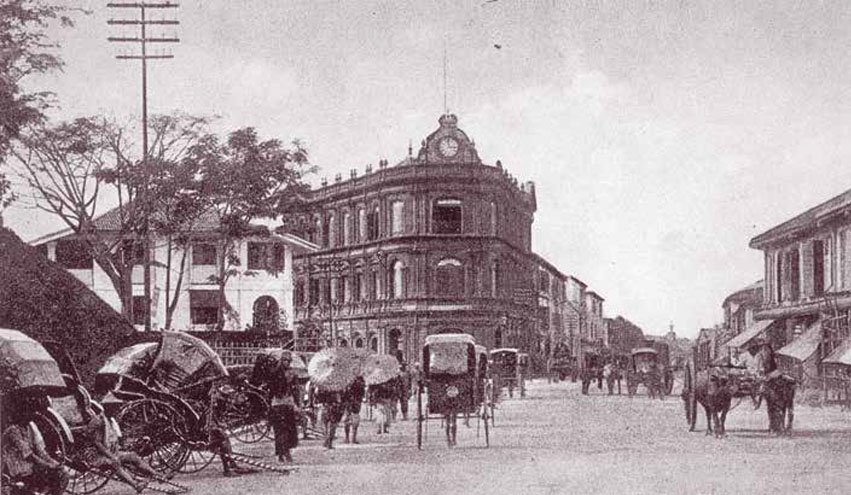

The Boustead Institute, at the junction of Anson Road and Tanjong Pagar Road, succeeded the Sailor’s Rest started in 1882 by a missionary named Miss Sophia Cooke to provide shelter and food for homeless sailors. The Boustead Institute, named after the English philanthropist Edward Boustead, continued to look after the welfare of destitute sailors. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Boustead Institute, at the junction of Anson Road and Tanjong Pagar Road, succeeded the Sailor’s Rest started in 1882 by a missionary named Miss Sophia Cooke to provide shelter and food for homeless sailors. The Boustead Institute, named after the English philanthropist Edward Boustead, continued to look after the welfare of destitute sailors. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Sophia Blackmore

Another missionary society that left a deep impact on Singapore was the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS; see text box below) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America. More familiar is the name Sophia Blackmore, its most well-known missionary in Singapore.

Miss Sophia Blackmore (seated, middle), a missionary of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America, posing with students of Methodist Girls’ School in this photo taken in 1915. She started the Tamil Girls’ School in 1887, which later accepted girls of other nationalities. By the 1890s, the school had been renamed the Methodist Girls’ School. Lee Brothers Studio

Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Miss Sophia Blackmore (seated, middle), a missionary of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America, posing with students of Methodist Girls’ School in this photo taken in 1915. She started the Tamil Girls’ School in 1887, which later accepted girls of other nationalities. By the 1890s, the school had been renamed the Methodist Girls’ School. Lee Brothers Studio

Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1887, the Minneapolis branch of the WFMS sent Miss Blackmore, who was Australian by birth, to Singapore. This was in response to a call from Reverend William Oldham for a woman missionary to work with the mothers Anglo-Chinese School (ACS) that he had started in 1886. Miss Blackmore was a true pioneer in that she was the first unmarried female Methodist missionary sent to Singapore.21

SOCIETY FOR THE PROMOTION OF FEMALE EDUCATION IN THE EAST

The Society for the Promotion of Female Education in the East (SPFEE) was founded in 1834 in London in response to an appeal by Reverend David Abeel for female missionaries to work among women in India and China. Also known as “the Society for Promoting Female Education in China, India and the East” and “the Female Education Society”, it was the first women’s missionary society ever to be formed.22

As an interdenominational society, the primary objective of the SPFEE was to establish schools in China, India and elsewhere in the East. Between 1834 and 1899, the SPFEE sent missionaries to Melaka, Singapore, India, China and Japan, as well as to the Middle East – specifically Palestine and Syria – for this purpose. In 1899, the society was dissolved following the death of its secretary and its work was taken over by other missionary societies. Besides Miss A. Grant and Miss Sophia Cooke, other SPFEE missionaries sent to Singapore included Miss Gage-Brown, who took over the Chinese Girls’ School following the death of Miss Cooke, and Miss Elizabeth Ryan, who worked with Miss Cooke at the Chinese Girls’ School and the Young Women’s Christian Association.23

In August 1887, Miss Blackmore started the Tamil Girls’ School in a shophouse at 33 Short Street.24 Over time, the school took in girls of other nationalities. It relocated several times, first to the Christian Institute on Middle Road, then back to a purpose-built building in Short Street. By the 1890s, the school had been renamed Methodist Girls’ School.25 In the 1920s, the school relocated to Mount Sophia and remained there for the next seven decades.26

Not one to rest on her laurels, just a year later, in August 1888, Miss Blackmore started a school for Chinese girls in the home of businessman Tan Keong Siak – known as Telok Ayer Chinese Girls’ School. In 1912, the school moved from Cross Street to Neil Road and was renamed Fairfield Girls’ School in honour of a donor named Mr Fairfield.27

Fairfield Girls’ School at its Neil Road premises. c.1920. Miss Sophia Blackmore started the school in 1888 for Chinese girls and called it Telok Ayer Chinese Girls’ School. When the school moved from Cross Street to Neil Road in 1912, it was renamed Fairfield Girls’ School. The school was renamed Fairfield Methodist Girls’ School in 1958. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Fairfield Girls’ School at its Neil Road premises. c.1920. Miss Sophia Blackmore started the school in 1888 for Chinese girls and called it Telok Ayer Chinese Girls’ School. When the school moved from Cross Street to Neil Road in 1912, it was renamed Fairfield Girls’ School. The school was renamed Fairfield Methodist Girls’ School in 1958. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.It was one thing to set up schools, but it was another to convince parents to send their girls to be educated. At the time many parents thought it was pointless for girls to go to school. Not to be defeated, Miss Blackmore went from house to house (particularly in the Telok Ayer and Neil Road areas) both to proselytise and to convince parents of the value of education and to send their daughters to school.28

The work was exhausting, but the women were motivated by a higher calling. One of the teachers in the school, a WFMS missionary, wrote:

“It was not easy work. It has meant patient working and praying. It has meant going to the homes and bringing them to school by love and sometimes almost by force. Day after day we have had to go to each home for the girls. It has meant outside work and assistance in trying to keep dull ones up to the level of the others. Many times I have left my classroom alone and gone to a home to get back a girl. Sometimes, after getting her part of the way, she would run home again and leave me, but I have never gone back to school under such circumstances without taking her back in a gentle, loving way.”29

Between 1887 and 1892, Miss Blackmore was the sole representative of the WFMS in Singapore although she was helped by local Eurasian ladies. In 1892, the WFMS sent out two more female missionaries – Miss Emma Ferris and Miss Sue Harrington – to Singapore to assist Miss Blackmore.30

In 1890, Miss Blackmore established the Deaconess Home as a base for WFMS work in Singapore. The home served as a residence for female missionaries (known as deaconesses) and also took in abandoned babies, orphans and young girls sold into slavery (known as mui tsai in Cantonese). In 1912, the home was renamed Nind Home after Mrs Mary C. Nind, the secretary of the Minneapolis branch of the WFMS.31

WOMAN’S FOREIGN MISSIONARY SOCIETY

The Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America was founded in Boston by Mrs William Butler and Mrs Edwin Parker, both wives of missionaries, in 1869. Both saw the need for female missionaries to work with women in India as teachers, doctors and even preachers. Thus, they established the WFMS with the aim of “engaging and uniting the efforts of the women of the church in sending out and supporting female missionaries, native Christian teachers and Bible women in foreign lands”.32

The WFMS was critical to the success of Methodist Girls’ School (MGS) and Fairfield Methodist School, especially in the period before World War II. The society provided both the funds and personnel to keep the schools running. All the principals of MGS and Fairfield in the pre-war period were WFMS missionaries, and most of them were unmarried. Several of its principals and teachers worked at both schools, either concurrently or at different points in time.33 Besides the school in Singapore, WFMS missionaries also managed Methodist schools in Malaya, such as those in Taiping (Perak), Ipoh (Perak) and Kuala Lumpur.34

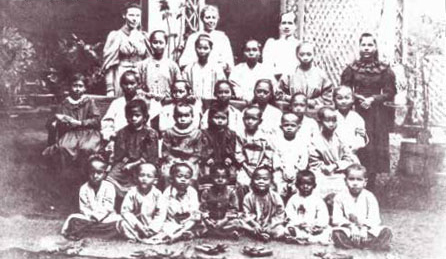

Miss Sophia Blackmore (back row, middle) with fellow missionaries from the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America and charges at the Deaconess Home, 1890s. She had established Deaconess Home as a base for WFMS work in Singapore in 1890. Morgan Betty Bassett Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Miss Sophia Blackmore (back row, middle) with fellow missionaries from the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church of America and charges at the Deaconess Home, 1890s. She had established Deaconess Home as a base for WFMS work in Singapore in 1890. Morgan Betty Bassett Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In addition to their work in schools, WFMS missionaries were active evangelists.35 Miss Sophia Blackmore, for instance, helped Methodist pastor Reverend William Shellabear set up the Baba Church (later known as Middle Road Church) in Middle Road.

One little known accomplishment of the WFMS was the establishment of the Rescue Home for “fallen” women in 1894. Two years earlier, WFMS missionary Miss Josephine Hebinger had been sent to Singapore to rescue Chinese and Japanese girls sold into prostitution. Miss Hebinger was released from her work in 1894 when she announced her plans to get married.36 It is not known what happened to the rescue home.

Sisters of the Holy Infant Jesus (IJ)

Besides the Protestant missionaries, Catholic nuns were also among the pioneers who provided education for girls. In February 1854, four nuns from the Institute of the Charitable Schools of the Holy Infant Jesus of St Maur in France arrived in Singapore. Reverend Mother St Mathilde, Sister St Appollinaire, Sister St Gaetan and Sister St Gregoire formed the core team that ran the school that came to be known as the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. The convent was the idea of Reverend Father Jean-Marie Beurel of the Missions Étrangères de Paris, who had started St Joseph’s Institution for the education of boys in 1852. He wanted the convent to be a safe place that would house a school for girls, an orphanage and an asylum for destitute widows.37

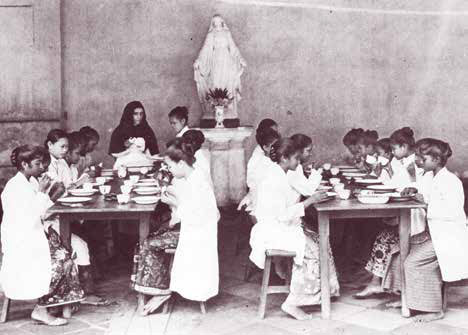

Orphans having a meal at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus in 1924. In addition to a school, the convent also ran an orphanage that accepted and cared for orphans and abandoned babies. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Orphans having a meal at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus in 1924. In addition to a school, the convent also ran an orphanage that accepted and cared for orphans and abandoned babies. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Established in 1854, the convent, known as Town Convent due to its location on Victoria Street in the city area, was the first Catholic mission school for girls in Singapore. In addition to running a day school, it also had an orphanage that accepted and cared for orphans and unwanted babies. Many of these babies were found on the doorsteps of the convent wrapped in rags or newspapers, abandoned by their mothers who could not care for them. The babies were often disabled, deformed or weak, and were usually girls.38

The IJ Sisters, as they came to be known, provided moral and domestic education for their charges, including classes in sewing, knitting and cooking as well as simple reading, writing and arithmetic. Gradually, the Sisters went on to establish several more convent schools throughout Singapore.39

The IJ Sisters were also actively involved in medical work. In his 1885 report, the Resident Surgeon of the General Hospital outlined in his report the Sisters’ work as nurses in the hospital:

“I am glad to report that, during this year, the introduction of Female Nurses has become an accomplished fact. The Nurses are Sisters from the Convent in Singapore, and they entered on their duties on August 1st. They have shewn [sic], and are shewing [sic], great interest in their work, and are very careful, and quick to learn. The improvement in the appearance of the hospital wards since the Nurses came is very marked, and the relief given to the Surgeon, and the Apothecaries in their attendance on bad cases is already great, and will in time be greater.”40

Up to that point, nursing work at the General Hospital was mainly carried out by apothecaries, dressers, ward stewards, servants and even convicts.41 The Sisters, although not professionally trained, became the first group of dedicated nurses in Singapore, and their services helped ease much of the staff’s workload. As part of their duties, the IJ Sisters attended to the patients, received hospital rations and looked after the servants.42

Nonetheless, the IJ Sisters’ involvement in nursing was short-lived. In May 1900, the Convent withdrew the Sisters’ services following a disagreement with the government. Trained nurses from the Colonial Institute in England replaced the Sisters.43

CATHOLIC SCHOOLS FOR GIRLS

Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) on Victoria Street – also known as Town Convent – founded in 1854 was the first of the CHIJ schools to be established in Singapore for girls.

In the 20th century, the Catholic order of the Holy Infant Jesus Sisters from France established eight more CHIJ schools: CHIJ Katong Convent (1930), CHIJ St Nicholas Girls’ School (1933), CHIJ St Theresa’s Convent (1933), CHIJ St Joseph’s Convent (1938), CHIJ (Bukit Timah) (1955), CHIJ Our Lady of the Nativity (1957), CHIJ Our Lady of Good Counsel (1960) and CHIJ Kellock (Primary) (1964).44

In 1964, the Town Convent was separated into primary and secondary schools and, in 1983, moved from its Victoria Street premises to Toa Payoh, where it remains today.

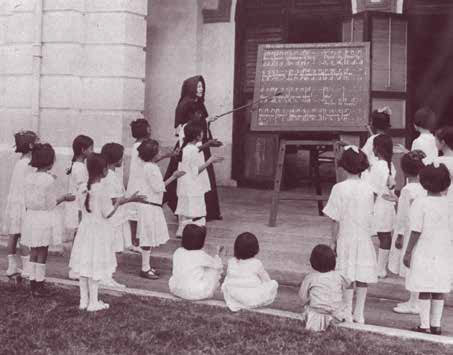

A music class in session at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus in 1924. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A music class in session at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus in 1924. Sisters of the Infant Jesus Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Dr Jaime Koh is founding director of The History Workroom LLP and adjunct professor at the Culinary Institute of America (Singapore) where she teaches History and Cultures of Asia. She has authored several books and various articles on Singapore’s history.

Dr Jaime Koh is founding director of The History Workroom LLP and adjunct professor at the Culinary Institute of America (Singapore) where she teaches History and Cultures of Asia. She has authored several books and various articles on Singapore’s history.

NOTES

-

Home, C.S. (1908). The story of the L.M.S., with an appendix bringing the story up to year 1904 (p. 10). Blackfrairs: London Missionary Society. Retrieved from Missiology website. ↩

-

Kirkwood, D. (1993). Protestant missionary women: Wives and spinsters (pp. 23–42). In F. Bowie, D. Kirkwood & S. Ardener (Eds.), Women and missions: Past and present: Anthropological and historical perceptions (p. 25). Oxford: Berg Publishers. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Kirkwood, 1993, p. 26. ↩

-

Kirkwood, 1993, p. 34. ↩

-

Kirkwood, 1993, p. 32; Williams, P. (1993). The missing link: The recruitment of women missionaries in some English evangelical missionary societies in the nineteenth century (pp. 43–69). In F. Bowie, D. Kirkwood & S. Ardener (Eds.), Women and missions: Past and present: Anthropological and historical perceptions (p. 56). Oxford: Berg Publishers. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Saw, S.H. (2012). The population of Singapore (pp. 31–32). Singapore: ISEAS. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW) ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, pp. 155, 353). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819–1988 (pp. 59–64). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]); Kiong, B.H. (1953). Educational progress in Singapore, 1870–1902 (p. 4). (Unpublished academic exercise, University of Malaya).; Blackmore, S. (n.d.). A pioneer in Malaya. Singapore: MGS Heritage Centre. (Unpublished manuscript) ↩

-

O’Sullivan, R.L. (1990). A history of the London Missionary Society in the Straits Settlements (c 1815–1847) (pp. 132–133) (PhD thesis). London: University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies. (Call no.: RCLOS 266.0234105957 OSU); Buckley. C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 77). Singapore: Fraser & Neave. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC-[HIS]) ↩

-

William E. (1844). A history of the London Missionary Society (Vol. 1) (pp. 569–570). London: John Snow. (Not available in NLB holdings); O’Sullivan, 1986, pp. 99, 133–134; Turnbull, 1989, p. 60. ↩

-

Lee, Y. M. (2002). Great is thy faithfulness: The story of St Margaret’s School in Singapore (pp. 27, 28, 30). Singapore: St Margaret’s School. (Call no.: RSING q373.5957 SAI) ↩

-

Lee, 2002, pp. 30–31; O’Sullivan, 1986, p. 134; Sng, B.E.K. (2003). In His good time: The story of the church in Singapore, 1819–2002 (p. 62, 63, 78, 86). Singapore: Bible Society of Singapore: Graduates’ Christian Fellowship. (Call no.: RSING 280.4095957 SNG) ↩

-

Song O.S. (2020). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. (p. 78). Singapore: National Library Board Singapore. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Walker, E.A. (1899). Sophia Cooke, or, forty-two years’ work in Singapore (pp. 5, 28-29). London: E. Stock. [Call no.: RRARE 287.10924 WAL; Microfilm no.: NL 11273]; Sng, 2003, pp. 65–66; Makepeace, Brooke & Braddell, 1991, p. 462. ↩

-

Ragged schools referred to the independently run charity schools the United Kingdom in the 19th century. These provided free education, food and lodging for the destitute. See Ragged University. (n. d.). Education history: A brief history of Ragged Schools. Retrieved from Ragged University website. ↩

-

Tiedemann, R.G. (2009). Reference guide to Christian missionary societies in China: From the sixteenth to the twentieth century (p. 213). Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. (Call no.: R 266.0095103 TIE); Seton, R. E. (2013). Western daughters in Eastern lands: British missionary women in Asia (p. 95). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. (Call no.: R 266.0234105082 SET); Lee, 2002, p. 70. ↩

-

National Library Board (2014, December 16). St Margaret’s School written by Fiona Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Walker, 1899, p. 37; Young Women’s Christian Association. (1995). Young Women’s Christian Association: 1875–1995 (p. 16). Singapore: Young Women’s Christian Association, (Call no.: RSING 267.59597 YOU); Young women’s association. (1898, January 3). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Walker, 1899, pp. 73, 83; Doraisamy, T.R. (Ed.). (1987). Sophia Blackmore in Singapore: Educational and missionary pioneer 1887–1927 (p. 17). Singapore: General Conference Women’s Society of Christian Service, Methodist Church of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 266.70924 SOP); The Sailor’s Rest. (1883, November 17). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 13; Tyers, R. (1973, May 4). Our heritage. New Nation, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Sng, 2003, pp. 66–67 ↩

-

Lau, E. (2008). From mission to church: The evolution of the Methodist Church in Singapore and Malaysia: 1885–1976 (pp. 7, 12, 15). Singapore: Genesis Books. (Call no: RSING 287.095957 LAU) ↩

-

Seton, R.E. (2013). Western daughters in Eastern lands: British missionary women in Asia (pp. 13–14). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. (Call no.: R 266.0234105082 SET); University College London. (2011, April 13). UCL Bloomsbury Project: Society for Promoting Female Education in China, India, and the East. Retrieved from UCL Bloomsbury Project website. ↩

-

Untitled. (1897, November 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 312; Death of Miss E. Ryan. (1923, December 17). The Straits Times, p. 8; C. E. Z. M. S. work. (1928, July 10). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Voke, R. (1920, August). History of the MGS, Singapore. The Malaysia Message, 29 (11), 82. Singapore: The Methodist Church Archives. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The Malaysia Message, Jan 1893, p. 38. ↩

-

Methodist Girls’ School. (1957). Methodist Girls’ School Singapore: Seventieth anniversary souvenir magazine: 1887–1957 (p. 30). Singapore: Methodist Girls’ School. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 MET); Blackmore, S. (n.d.). A record of 40 years of woman’s work in Malaya 1887–1927 (p. 3). Singapore: The Methodist Church Archives. (Not available in NLB holdings.); Methodist Girls’ School. (1900, February 27). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: In 1992, Methodist Girls’ School moved to its current premises in Bukit Timah, specifically Blackmore Drive, which is named after its founder Miss Sophia Blackmore.] ↩

-

Sng, 2003, pp. 113–114; Fairfield Methodist School (Secondary). (2015). School history. Retrieved from FMSS website. [Note: Over the years, Fairfield Girls’ School has changed its name several times: Fairfield Methodist Girls’ School in 1958; Fairfield Methodist Primary School and Fairfield Methodist Secondary School in 1983 when it moved to Dover Road and became co-educational; and finally, Fairfield Methodist School (Primary) and Fairfield Methodist School (Secondary) in 2009.] ↩

-

Miss Hemingway writing in 1899. Quoted in Sng, 2003, pp. 114–115. ↩

-

Blackmore, n.d. ↩

-

Lau, 2008, p. 16; Blackmore, S. (1928). A record of forty years of women’s work in Malaya, 1885–1925 (p. 1). (Unpublished manuscript); Lim, L.U.W. (1987). Memories, gems and sentiments: 100 years of Methodist Girls’ School (p. 5). Singapore: Methodist Girls School. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Blackmore, n.d; See various issues of The Malaysia Message from 1890 to 1941. Singapore: The Methodist Church Archives. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

See for example the report on WFMS evangelistic work in Minutes of the Malaysia Mission Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. (1895, February 14–20) (pp. 32–35). Retrieved from Images library website; Lau, 2008, pp. 27, 46. ↩

-

Doraisamy, 1987, p. 56; Lau, 2008, p. 16; The Malaysia Message, Jun 1894, p. 88; Minutes of the Malaysia Mission Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, 14–20 Feb 1895, pp. 15.,17. ↩

-

Kong, L., Low, S.A., & Yip, J. (1994). Convent chronicles: History of a pioneer mission school for girls in Singapore (p. 56). Singapore: Armour Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 373.5957 KON); Meyers, E. (2004). Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus: 150 years in Singapore (p. 62). Penang, Malaysia: The Lady Superior of Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus. (Call no.: RSING q371.07125957 MEY) ↩

-

Kong, Low & Yip, 1994, p. 56; CHIJ Secondary. (2017). IJ communities and schools. Retrieved from CHIJ Secondary website. ↩

-

Annual medical report on the civil hospitals in the Straits Settlements for the year 1885. See Straits Settlements. Legislative Council. (1886). Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements (with appendices) for the year 1886. Singapore: Government Printing Office. [Microfilm no.: NL 1107] ↩

-

Khoo, H. H. (1955). Medical services in the Straits Settlements, 1867–1905 (p. 55) (Unpublished thesis). Singapore: University of Malaya. (Not available in NLB holdings); Viji Mudeliar, V., Nair, C.R.S., & Norris, R.P. (1983). Development of hospital care and nursing in Singapore (p. 18). Singapore: Ministry of Health. Retrieved from PublicationSG. ↩

-

Annual medical report on the civil hospitals of the Straits Settlements for the year 1893. See Straits Settlements Legislative Council. (1893). Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements (with appendices) for the year 1893. Singapore: Government Printing Office. [Microfilm no.: NL 1107] ↩

-

Untitled. (1900, May 14). The Straits Times, p. 2; Legislative Council. (1990, February 28). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

CHIJ Secondary. (2017). IJ communities and schools. Retrieved from CHIJ Secondary website. ↩