Hunting Down the Malayan Mata Hari

Ronnie Tan pieces together the fascinating story of Lee Meng, the Malayan Communist Party female agent who headed its courier network for a brief period in 1952.

On 16 June 1948, three European planters were brutally murdered by communist guerillas in the Sungei Siput area in Perak state, in what was then known as Malaya.1 Two days later, Britain declared a state of Emergency in Malaya, with Singapore following suit on 24 June 1948. The battle for control of Malaya and Singapore between the British and the Malayan Communist Party (MCP; also known as the Communist Party of Malaya) had begun, and it would not end until 31 July 1960.

During the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), the MCP carried out labour strikes, assassinations and other acts of violence aimed at bringing about social and industrial disruption in Malaya and Singapore.

In Singapore, the MCP tried to overthrow the British authorities “by means of subversion and terror”.2 Specific sections of society were targeted, including “students, factory workers, government servants, intellectuals, politicians, newspapermen, transport workers and dockhands”.3 The wealthy were not spared either − the murder of pineapple and rubber merchant Lim Teck Kin being a case in point.

To carry out its nefarious activities, the MCP’s Central Committee needed to communicate effectively with its rank-and-file members scattered throughout Malaya and Singapore. But as the MCP cadres had no access to wireless communications technology back then, they had to rely on “open and fragile jungle couriers”.4

As it turned out, communications – or the lack of, rather − was the MCP’s Achilles heel. To cite an example, communications between local branches of the Min Yuen (Mass People’s Movement) in Pahang, comprising MCP sympathisers, was so bad that one branch was not aware of the other’s activities even when the physical distance was small. Chin Peng, Secretary-General of the MCP then, himself admitted that the Sungei Siput killings “were the work of local cadres acting without an order from the Central Committee – even without its knowledge”.5

Chin Peng needed someone who was street smart and capable of managing its communications courier system in north and central Malaya, and decided that the best person for the job as MCP’s “head courier” was a young lady named Lee Ten Tai (alias Lee Meng). Lee was leader of the Kepayang Gang6 which operated in Ipoh, the state capital of Perak.

Lee Meng: Malayan Mata Hari

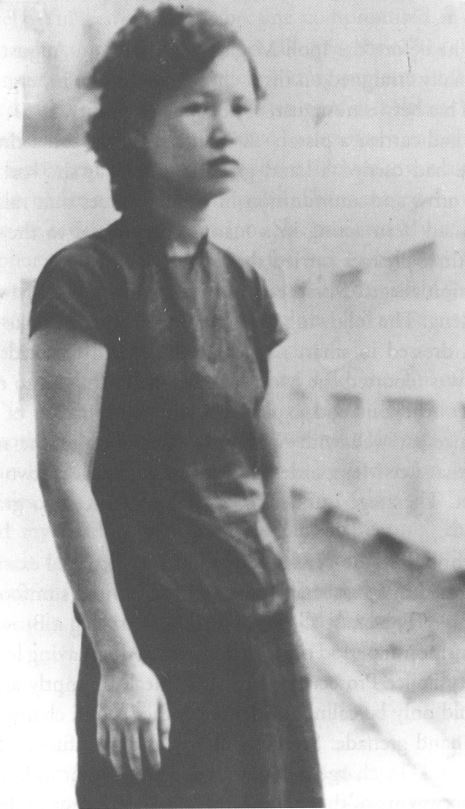

Lee Meng already had a reputation as a cunning fighter and organiser. She was also “one of the most ruthless and capable members of the Min Yuen” in Ipoh.7 Surrendered and captured communist guerrillas claimed that Lee had ordered a number of cold-blooded executions that were carried out by Communist Special Service squads.8 While Chin Peng described her as “dedicated, active and brave” he also commented that she “lacked caution” and was reckless in her operational style.9

Lee Meng was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1926 and moved to Ipoh at the age of five. She was believed to have worked as a Chinese school teacher in Teluk Anson (now known as Teluk Intan), Perak, during the British Military Administration period – the interim military government established in Singapore and Malaya after the Japanese surrender on 12 September 1945.10 Her father was unemployed and lived with her uncle and aunt, while her mother would be banished to China in 1950 after she was arrested for communist activities. Given Lee Meng’s disenfranchised background and her mum’s own involvement with the communists, it is not surprising that she readily joined the MCP in 1942 when she was recruited by her school teacher.

The courier network Lee Meng was ordered to set up required all messages to and from Chin Peng, or between local units and regimental commanders, to pass through it. During the early years of the Emergency, Lee Meng’s exact whereabouts were unknown as she had reportedly gone underground, living among Min Yuen units scattered around the jungle fringes of Malaya or in the vicinity of Ipoh.

By then, the Malayan Special Branch – instructed to flush out MCP members and sympathisers – had found out about Lee Meng’s activities and decided to penetrate the courier link she was heading and establish her whereabouts. The task of arresting Lee Meng and unravelling the network fell on the shoulders of Detective-Inspector Irene Lee Saw Leng.11

Detective-Inspector Irene Lee: Special Branch Officer

On the other side of the ideological divide was Detective-Inspector Irene Lee, who was herself a victim of the communists: in April 1951, her policeman husband, Detective-Corporal Jimmy Loke, was murdered by communist gunmen in Penang.12 After her husband’s death, Lee joined the police force as an inspector and was posted to Special Branch Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur.

Lee was highly regarded by her peers in Singapore’s Special Branch as a competent and experienced officer. She was not only a highly skilled markswoman but also “a brilliant lock-picker, an expert with a mini-camera, an accomplished thief (in the course of her duty)” and endowed with a “delicious sense of humour”, according to the British journalist and author Noel Barber.13

The Hunt for Lee Meng

The breakthrough in the hunt for Lee Meng came in early February 1952 following a raid on a communist guerrilla camp in Selangor. Captured documents from the deserted camp revealed the identity of a Chinese woman serving as a courier out of Singapore into Johor and who was believed to be the Singapore link in Lee Meng’s intricate courier network.

That woman was known as Ah Shu or Ah Soo, a Chinese school teacher and the wife of Wong Fook Kwang, alias Tit Fung, the leader of the Communist-controlled Workers Protection Corps in Singapore. Wong also had a hand in the murder of pineapple and rubber merchant Lim Teck Kin and others, including a policeman, a factory supervisor and a manager at Hock Lee Bus Company.

Once the identity of Ah Shu was established, the Special Branch sent Irene Lee to Singapore in February 1952 to track Ah Shu down and follow a complex trail that would ultimately lead to Lee Meng’s arrest and eventual banishment to China.

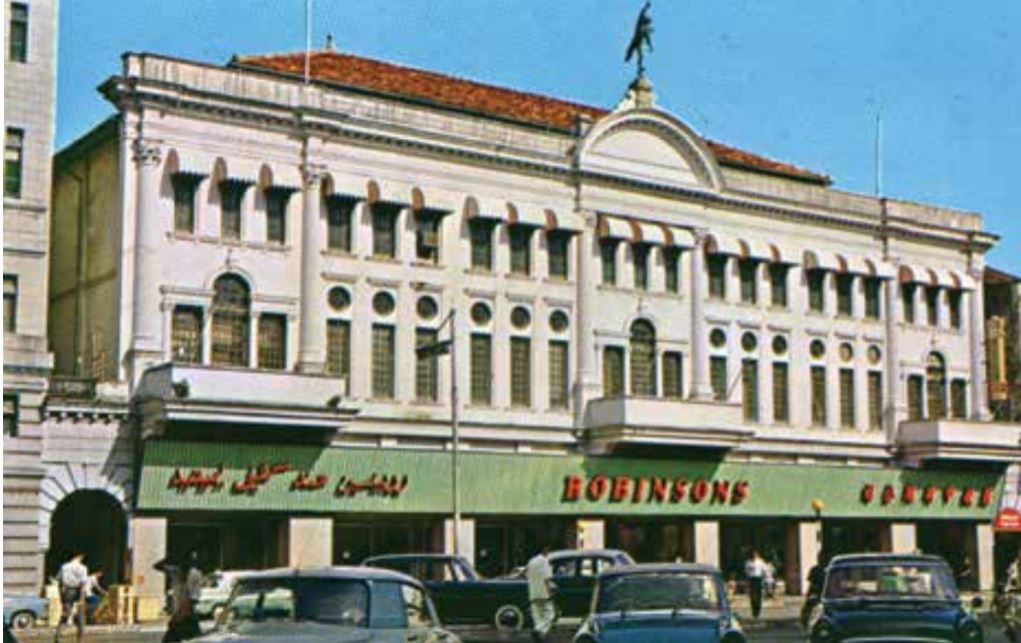

For three weeks, Ah Shu’s movements were closely monitored, particularly when she went shopping at Robinson’s department store, which was then located at Raffles Place. On a number of occasions, Lee observed Ah Shu unobtrusively from a safe distance as the latter “skillfully switch[ed] identical shopping bags”,14 believed to contain communist literature and messages, with another unidentified lady courier. The Special Branch knew then that both women had to be arrested.

At 5 pm one evening, Lee shadowed Ah Shu and watched her as she met the other lady to switch bags. No words were exchanged in the process. In the meantime, Lee’s male colleagues waited in an unmarked Special Branch car, with its engine running. As Ah Shu walked out of the store, Lee tailed her, initially on foot and then by trishaw, with the Special Branch car following behind at a discreet distance.

Meanwhile, the other woman was quietly arrested by Special Branch officers inside Robinsons. Along Stamford Road, just by YMCA’s tennis courts, Ah Shu alighted and started walking towards YMCA building, with Lee following behind. At the right moment, Lee gave the signal for the unmarked Special Branch car to draw abreast. Simultaneously, Lee stuck a gun into Ah Shu’s back and ordered her to get into the car, which then sped off to a secret Special Branch “safe house” on the outskirts of the city.

On arrival, Ah Shu was searched by a woman constable, and a message hidden in a sealed tin of Johnson’s baby powder was found in her shopping bag. The tin’s bottom had been skillfully removed to contain the message. After the message had been extracted and photographed, it was then carefully put back into another identical tin, “which meant that a detective had to persuade an irate shopkeeper to open up [late at night] and sell him another [unblemished] tin so the message could be replaced”.15

All that remained was for Lee to persuade Ah Shu to cooperate with the Special Branch and return to the jungle with the message that was now hidden in the new tin of baby powder. Lee managed to shake Ah Shu’s resolve by showing her a photograph taken in the safe house – in which she was seated with two smiling uniformed Malay policemen – with the warning that the photograph would not only be published widely in the Chinese press in Singapore, but 50,000 copies of the photograph would be dropped by plane around the area where she operated. Left with little room to manoeuvre, Ah Shu agreed to cooperate and carry the message to Johor and pass it on to the next link in the courier chain.

The information Ah Shu supplied led Special Branch officers to an address in Yong Peng, Johor, where another unnamed woman courier along the chain lived. To gain her trust, Lee posed as a fellow communist courier. Her ruse worked and the woman believed her.

Lee then persuaded the woman to go out for lunch. The former made up a story about how she had murdered a policeman in an ambush not far from Yong Peng three days earlier. The meal would be a celebration of Lee’s daring feat. After lunch, Lee flagged a taxi (conveniently driven by a Special Branch officer) and both got in. Four hours later, the woman courier arrived at the Holding Centre in Kuala Lumpur with Lee by her side.

After dinner, the woman was ushered into a small room for interrogation during which Lee managed to convince her that the only way out of this difficult situation was to cooperate with the police and become a Special Branch double agent. She agreed and in time became one of its most valuable double agents. The double agent realised that she had “wasted the best years” of her life working for the communists, and even asked her superiors to be allowed to work with Lee.16

The Trail to Kuala Lumpur

The trail next led to a male rubber tapper in Jenderak rubber estate, near Jerantut, Pahang. Every morning, Lee turned up at the rubber estate, posing as a rubber tapper. After “work” was done around 11.30 am, Lee’s real job began, shadowing the after-work activities of a male rubber tapper named Chen Lee, a member of the Min Yuen.

Lee shadowed Chen Lee for several weeks, and eventually, her efforts paid off; she obtained evidence that Chen Lee was a communist courier and had been smuggling food to food dumps meant for communist terrorists hiding out on the fringes of the jungle. After ascertaining Chen Lee’s involvement in clandestine activities, she arranged to have him arrested. One day, when Chen Lee was walking along a lonely road while out on one of his regular visits to drop off supplies for his comrades in the jungle, he was nabbed by Special Branch officers and bundled into the back of a taxi, with Irene Lee beside him.

Inside the taxi, Lee read out the riot act to her captive, spelling out the various activities Chen Lee had carried out for the Min Yuen, including filling his bicycle pump with rice, buying drugs and hiding them in the jungle and buying three bullets – a crime punishable by death in Malaya. Chen Lee initially denied the charges but after Lee produced enough concrete evidence of his crimes, he decided to cooperate and divulge the next link in the courier chain – a bookshop in Batu Road, Kuala Lumpur.

As Batu Road was a busy street, the raid had to be carefully planned without raising the suspicion of the bookshop owner and communist cadres lurking in the neighbourhood. Otherwise, contacts in the courier chain would be alerted and go into hiding. For this reason, the Special Branch hatched an elaborate plan that involved the acquisition of a pineapple estate and cannery in Johor that exported canned pineapples. A lorry carrying a cargo of canned pineapples to be shipped out to Britain the next day via Penang would pass through Kuala Lumpur at a particular time.

In order not to arouse the suspicion of Min Yuen members in the area, the lorry’s movement was timed so that it “fitted in perfectly” with the shipment schedule.17 The lorry would suffer a rear wheel puncture just as it passed by the bookshop. To replace the wheel, the lorry would have to be jacked up. However, due to the weight of the goods, the crates packed with tins of pineapple would be temporarily unloaded while the wheel was changed. Now those loitering in the area, even if they were communist sympathisers or spies, had to help the lorry driver and his workers unload the crates, otherwise something would seem amiss. Since the crates could not be placed on the road without impeding traffic flow, they were conveniently stacked against the door of the bookshop.

Unaware to passers-by, Irene Lee was hiding in one of those crates. While the men went about changing the wheel, Lee opened the trapdoor of the crate, “picked the front door lock [of the bookshop], entered the shop, searched it, made photocopies and was back in her packing case” – all before the lorry was reloaded with the crates.18 From the evidence Lee found in the bookshop, the Special Branch ascertained that the nerve centre of the courier network was located in Ipoh and not Kuala Lumpur as it originally thought, and that it was run by a woman.

The Cat Finally Gets Her Mouse (in Ipoh)

Two blocks away from the FMS Bar in Ipoh, the communist courier trail which began in Singapore on February 1952 finally ended at a small, nondescript house in Lahat Road. The house “turned out to be the undercover communication post coordinating the secret courier network reporting to the CPM’s Central Committee”.19

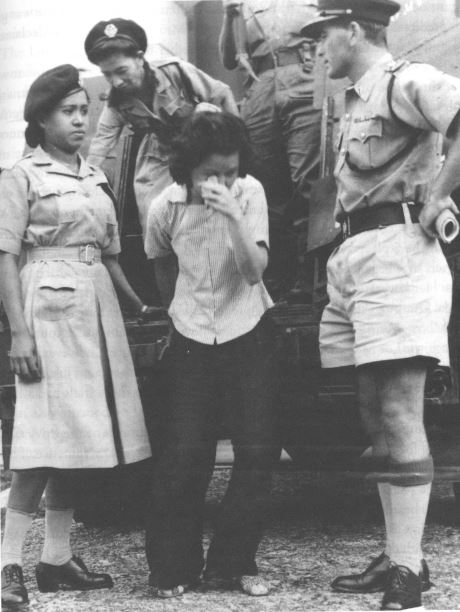

Special Branch officers kept the house under 24-hour surveillance. At 8 pm on 24 July 1952, a raid was carried out. Irene Lee’s knock on the door was answered by her nemesis, Lee Meng. Stunned by this stranger at the door, Lee Meng and her friend Cheow Yin, who was also in the house at the time, were caught unawares and unarmed, and quickly apprehended.

The noose around Lee Meng tightened further when she slipped up in her attempt to produce her identity card. Issued in Ipoh in 1949, the card did not bear her name but that of another person by the name of Wong Nyuk Yin.20 Lee Meng claimed that she had been in Ipoh for just over two years and was living in Singapore prior to that. However, Irene Lee caught on to her lie: it was impossible for Lee Meng to be in Singapore in 1949 and yet receive “her” identity card in Ipoh at the same time.

Upon further questioning, Lee Meng buckled. In addition, the old Chinese desk with a false drawer that Chin Peng had ordered her to buy earlier was found in the house.21 Inside the drawer were communist documents waiting to be disseminated – ample proof of her role as being part of Chin Peng’s courier network. Lee Meng was subsequently remanded in Taiping Jail to await trial.

The Aftermath

Lee Meng

When Lee Meng appeared before the Magistrate’s Court in Ipoh on 6 August 1952, she was charged with three offences – being armed with a pistol and a hand grenade between August 1948 and September 1951 in Ipoh, and for consorting “with persons who were carrying firearms and acting in a manner prejudicial to the maintenance of good order”.22 No references were made to her activities as a courier to avoid compromising Special Branch operations that were going on at the time and neither was she charged as a communist. The Special Branch hoped that when Chin Peng received news of her arrest, he would assume that her courier activities had not been exposed.

In court, she denied that she was Lee Meng but Lee Ten Tai. She also denied ever living in the jungle and claimed that she did not know what a hand grenade was. However, several communist guerrillas testified in court that they had seen Lee Meng armed with grenades and was a senior MCP member.

Lee Meng was initially found not guilty during her first trial on 27 August 1952. A retrial was ordered on 10 September the following month. This time, Lee Meng, now dubbed the “grenade girl” by the press,23 was pronounced guilty and sentenced to death.

According to one account, while Lee Meng was remanded in Taiping Jail, she tried to seduce the male jailer on night duty in an effort to become pregnant. She knew that British law did not permit a pregnant woman to be executed. Unfortunately for Lee Meng, the authorities discovered the plot and replaced him with a female jailer.

During her retrial on 10 September 1952, Lee Meng appealed to the Malayan High Court against her death sentence but her case was dismissed on 14 November. She was returned to Taiping Jail to await her fate while her lawyers lodged an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London on 14 February 1953. The appeal was unsuccessful and a petition for clemency was then sent to the Sultan of Perak on 23 February 1953. The petition was approved and just two weeks later on 9 March, Lee Meng’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in Taiping Jail. While in prison, she passed her time knitting shawls and even learned to speak “superb Malay”.24

But there was another twist to the Lee Meng story. Lee Meng’s trial had generated worldwide interest, with the government receiving petitions for her to be spared the death penalty. Moreover, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries and the United States and its NATO allies was in full swing. Both sides conducted espionage activities on each other to gain the upper hand in the battle for dominance.

It was against this backdrop, on 2 March 1953, that the Hungarian government offered to swap Lee Meng for a British businessman, Edgar Sanders, who was serving a 13-year jail sentence in Budapest for espionage. Almost overnight Lee Meng’s case became a cause celèbre.25 However, the offer of a prisoner swap was turned down by the British.

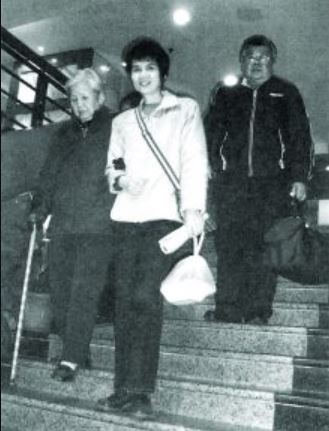

Lee Meng was incarcerated at Taiping Jail until her release and banishment to China on 23 November 1963 – the same fate that had befallen her mother in 1950. However, it was only in January 1964 that the Malaysian government announced her deportation. Before Lee Meng left, she asked the lawyers who defended her, the Seenivasagam brothers (Sri Padhmaraja and Darma Raja, popularly known as S.P. and D.R. Seenivasagam), to buy her two bicycles, a transistor radio, blankets, a mattress, several watches and some gold bangles so that she could bring these to China.

In China, she was reunited with her mother, whom she cared for until the latter passed on. She also met Chen Tien, Chin Peng’s “trusted aide and comrade”,26 and married him in 1965. He passed away on 3 September 1990 from lung cancer.27 In August 2007, Lee Meng visited Malaysia. During her visit, she called on one of her trial lawyers, Lim Phaik Gan, to thank her for “securing her release”.28 It was reported that Lee Meng passed away in Guangzhou, China, on 2 June 2012 at the age of 86.

Irene Lee

Following the successful capture and prosecution of Lee Meng, Irene Lee went on to serve in other capacities in the police force in Malaya. These included stints in the Penang Contingent, the Georgetown Police District Headquarters (1957) and the Federal Police Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur (1958), while serving as Chief of Women Police and, shortly thereafter, as a Woman Police Supervisor, with the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP).

On 12 October 1959, Lee was transferred to the Perak Contingent and served as an Inspector of ‘Á’ Branch. She was awarded the Colonial Police Medal for meritorious service in 1956.

Lee left the police force on 1 January 1960 “as a result of a disagreement with the Malayan authorities”29 and subsequently took up a secretarial job at an import firm in Singapore. She passed away on 12 May 1994 at the age of 72.

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts a research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts a research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

REFERENCES

Coroner returns murder finding. (1951, June 6). The Straits Times. p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Douglas, W.O. (1953). North from Malaya: Adventure on five fronts (p. 55). New York: Doubleday & Company. (Call no.: RCLOS 959 DOU).

Grenade case girl: I’m not that woman story of her 2 I-cards. (1952, August 29). Singapore Standard, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Irene Lee – from housewife to head of women police. (1958, August 14). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee Meng. (1953, February 24). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee Meng: Prison drama. (1953, March 10). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Leong, H.M. (1953, March 10). ‘Grenade girl’ Lee Meng is reprieved. Singapore Standard, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Malayan takes over as chief of women police. (1958, August 21). Singapore Standard. p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Malaysia History. (2012, June 30). The Malayan Emergency 1948–1960. Retrieved from Malayan History website.

Miller, S. (2012, April 16). Malaya: The myths of hearts and minds. Small Wars Journal. Retrieved from Small Wars Journal website.

National Archives of Malaysia. (2018, January 23). Formation of Malaysia 16 September 1963. Retrieved from National Archives of Malaysia website.

Pretty girl gave murder orders: Court told. (1952, August 28). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Selamat bin Sainayune. (2007). Polis wanita: Sejarah bergambar 1955–2007 (p. 279). Petaling Jaya: Kelana Publications Sdn Bhd. (Call no.: Malay R 363.208209595 SEL)

Such a surprise for Irene. (1956, January 4). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tay, M. (2008, May 31). Robinsons. The Straits Times, p. 67. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The grenade girl who also faced death. (1968, July 15). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Van Tonder, G. (2017). Malayan emergency: Triumph of the running dogs (p. 4). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. (Call no.: RSING 959.5104 VAN).

NOTES

-

Malaya was still under British rule in 1948. It gained independence on 31 August 1957 and became known as Malaysia on 16 September 1963 after representatives from Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore signed the Federation of Malaysia agreement on 9 July 1963. ↩

-

Clague, P. (1980). Iron Spearhead: The true story of a communist killer squad in Singapore (p. 3). Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 335.43095957 CLA). ↩

-

Chin, P. (2003). My side of history (p. 334). Singapore: Media Masters. (Call no.: RSING 959.5104092 CHI). ↩

-

Stockwell, A.J. (2006, November). Chin Peng and the struggle for Malaya. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 16 (3), 279–297, p. 286. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

According to Leon Comber, the Kepayang Gang was involved in several deadly hand grenade attacks around Perak in 1949. These included the attack on the offices of the Kin Kwok Daily News (an anti-Communist newspaper) on 1 October 1949 and an attack on a circus audience in Kampar that same year. ↩

-

Short, A. (2000). In pursuit of mountain rats: The communist insurrection in Malaya (p. 384). Singapore: Cultured Lotus. (Call no.: RSING 959.5104 SHO). ↩

-

The British Military Administration (BMA) ended when civilian rule was restored on 1 April 1946. See National Library Board. (2014). British Military Administration is established. Retrieved from HistorySG. ↩

-

Comber, L. (2008). Malaya’s secret police 1945–60: The role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency (p. 228). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; Australia: Monash Asia Institute. (Call no.: RSING 363.283095951 COM-[GH]). ↩

-

Such a surprise for Irene. (1956, January 4). The Straits Times. p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Barber, N. (1971). The war of the running dogs: How Malaya defeated the communist guerrillas, 1948–60 (p. 165). London: Collins. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 BAR-[JSB]). ↩

-

Barber, 1971, p. 170. Such an elaborate plan was warranted: when the crates were being loaded onto a UK-bound ship in Penang the following day, a dock labourer, likely a communist, approached the lorry driver to ask if his vehicle had indeed suffered a tyre puncture along Batu Road in Kuala Lumpur the previous day. ↩

-

‘I am not the bandit boss Lee Meng’, says woman, 24. (1952, August 29). The Straits Times. p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

After Lee Meng was handpicked to head the courier network, Chin Peng told her to acquire an old Chinese desk. It had a false drawer where she could conceal messages meant to be transmitted along the courier network. ↩

-

Lee Meng decision on Monday? (1953, March 7). Singapore Standard, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tai, S.O. (1964, January 29). It’s back to China for Lee Meng. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, P.G. (2012). Kaleidoscope: The memoirs of P.G. Lim (p. 141). Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, Petaling Jaya. (Call no.: RSEA 322.5950092 LIM). ↩

-

郑昭贤 [Zheng, Z.]. (2007). 《陈田夫人: 李明口述历史》(pp. 98, 101). Petaling Jaya: 策略资讯研究中心. (Call no.: Chinese RSEA 324.2595075092 ZZX). ↩