Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio

Gretchen Liu casts the spotlight on the Lee Brothers Studio Collection. Comprising some 2,500 images, this is the largest single collection of photographic portraits in the National Archives of Singapore.

Between 1910 and 1940, Lee Brothers Photographers was a well-known landmark along Hill Street. In the years before amateur photography became widespread, hundreds of its clients – the prospering and aspiring, the famous and unknown, Chinese, Indian, Malay and European, resident and visitor – climbed the wooden steps to the top floor of a shophouse at No. 58-4 in search of that small bit of immortality: the studio portrait.

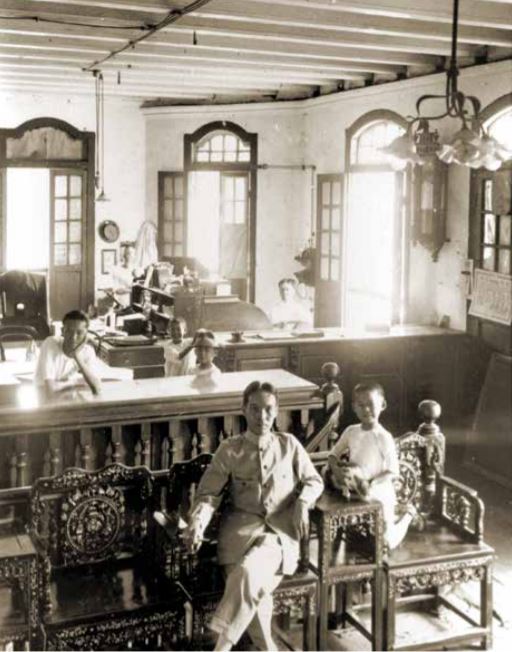

The brothers started their business in the three-storey shophouse located prominently at the corner of Hill Street and Loke Yew Street. The corner location was ideal because the additional windows provided the main source of illumination and kept exposure times to a minimum. Typical of Victorian photographers, the studio was equipped with decorative painted backdrops imported from Shanghai and Europe, and various props ranging from imitation masonry, drapery, potted plants and porcelain dogs to toys for children, rustic benches and handsome drawing room chairs.

All of the equipment was of the best quality while the processing chemicals were the purest available. The British-made main studio camera was a large wooden affair with squared bellows connecting the front lens panel with a rear panel carrying the focusing screen and the plate holder. It rested on a heavy wooden stand that could be raised, lowered or tilted so as to frame the sitter appropriately, and was fitted with cast-iron castors for mobility.

Sharing the work behind the camera – adjusting the lens, inserting the treated glass plates, calculating the exposure times, removing the plates and processing them in the darkroom – were the Lee brothers, King Yan (1877–1957) and Poh Yan (1884–1960). For over half a century, from 1940 until 1994, copies of over 2,500 of these original photographs and some glass plate negatives were kept by Poh Yan’s eldest son, Lee Hin Ming. The photographs were mostly excess or uncollected prints while the negatives had been deliberately set aside. In 1994, this collection was entrusted to the National Archives by 80-year-old Hin Ming, thus ensuring the survival of a unique and eloquent record of the people of Singapore in the early years of the 20th century.

A Family of Photographers

Lee King Yan and Lee Poh Yan belonged to a large Cantonese family from the village of Siu Wong Nai Cheun (literally “Small Yellow Earth Village”) in Nam Hoi county, Guangdong province. According to family lineage records, the village was founded by Lee Shun Tsai from Zhejiang province in the 13th century.1 From this village, members of the family ventured forth to operate more than a dozen photographic studios in Southeast Asia, including eight in Singapore.

King Yan and Poh Yan, who were born in China, belonged to the 21st generation and learned photography from their father, Lee Tit Loon. In its early days, the art of photography was considered a trade secret. In some European cities, photography was a protected profession that no one who had not served as an apprentice could join.2 In the Lee family, it was the brothers and sons who handled the camera and processed the plates, while employees were engaged as retouchers, finishers and mounters.

By 1900, Tit Loon was managing the successful Koon Sun Photo Studio at 179 South Bridge Road. He had four surviving sons, three of whom became photographers: King Yan, Poh Yan and Sou Yan. The fourth, Chi Yan, was sent by the Methodist mission to study in the United States and became a minister and teacher until his early death in the mid-1920s. When Tit Loon retired to his home village, Koon Sun Photo Studio was left in the hands of Poh Yan and Sou Yan.

King Yan, however, struck out on his own. By 1911, he had established Lee Brothers Photographers at 58-4 Hill Street, and by 1913, Poh Yan had joined him. Younger brother Sou Yan continued to run Koon Sun for several years, closing it around 1917 before returning to China.

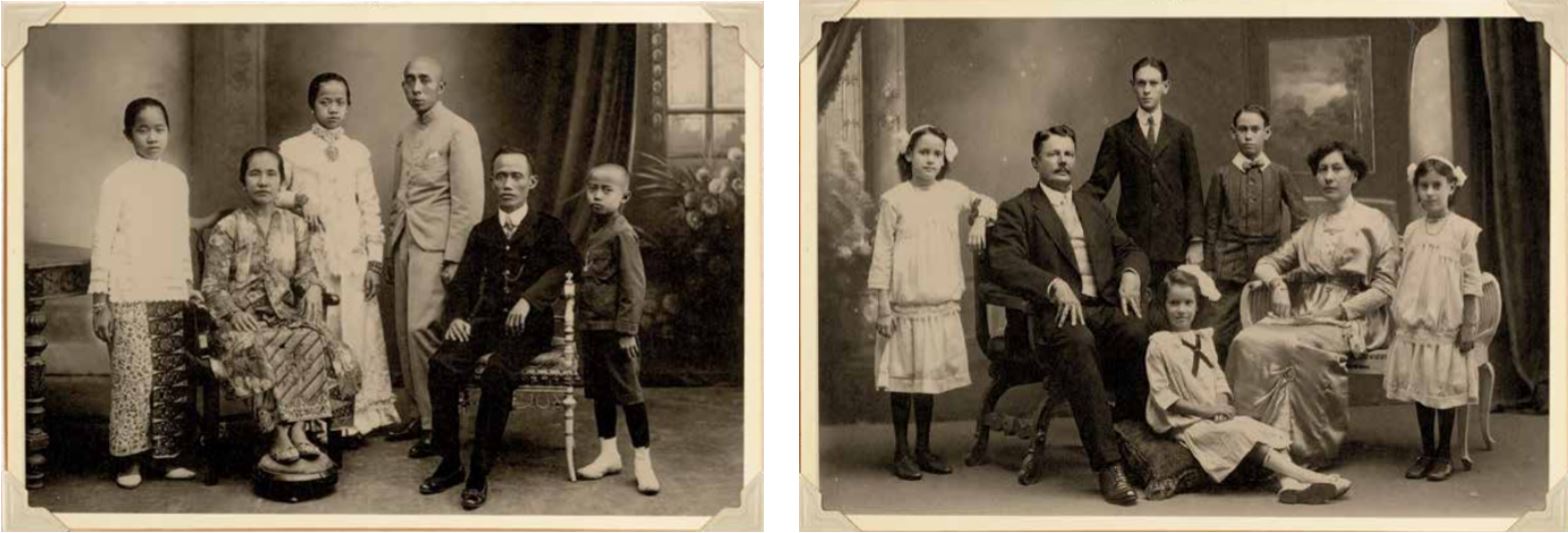

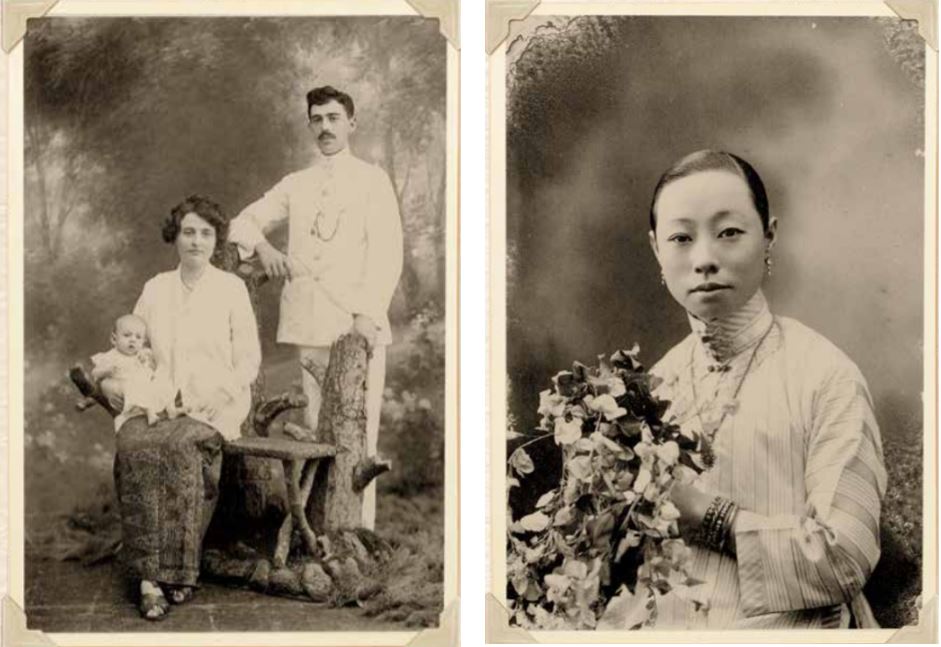

The move out of Chinatown and into the more salubrious Stamford Road area was significant. With a population of over 185,000, Singapore was one of the busiest ports in the world and the most cosmopolitan city in Asia. Nearly three-quarters of the population were Chinese, but there were large groups of peninsular Malays, Sumatrans, Javanese, Bugis, Boyanese, Indians, Ceylonese, Arabs, Jews, Eurasians and Europeans.3 Men still outnumbered women by eight to one but there was a steady increase in the number of Chinese women immigrants and more babies being born in the Straits Settlements,4 a fact reflected by the impressive number of baby and family photographs in the Lee Brothers Collection.

It wasn’t long before King Yan and Poh Yan were photographing many of the well-known personalities of the day, including Dr Lim Boon Keng, Mr and Mrs Song Ong Siang, Mr and Mrs Lee Choon Guan, Dr Hu Tsai Kuan, rubber planter Lim Chong Pang, rubber merchant Teo Eng Hock, banker Seet Tiong Wah, the families of Tan Kim Seng and Tan Kah Kee, and Dr Sun Yat Sen during his historic visits to Singapore.

Many of the photographs in Song Ong Siang’s landmark 1923 publication, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, were supplied by Lee Brothers Studio.5 The Methodist missionaries who patronised the brothers – both active church members – included Sophia Blackmore, the founder of Methodist Girls’ School.

The photographs of these luminaries are found among the many more captivating portraits of the anonymous, but obviously prospering, inhabitants of Singapore: plump satisfied towkays, formidable nonyas of all ages bedecked with exquisite jewellery, European merchants and their well-dressed wives, beguiling wedding couples and, perhaps most endearing of all, enchanting family portraits of all races.

In the early 1920s, the two brothers parted company on amicable terms and King Yan opened Eastern Studio on Stamford Road. The decision may have been dictated by domestic circumstances as both men had large and still growing families. The 1923 edition of Seaports of the Far East contained a highly flattering description of Eastern Studio that highlighted King Yan’s expertise: “One of the best photographers in Singapore is Mr Lee Keng (sic) Yan, proprietor of the Eastern Studio, who has been operating locally for thirty years, and is an expert in every branch of his trade”.6

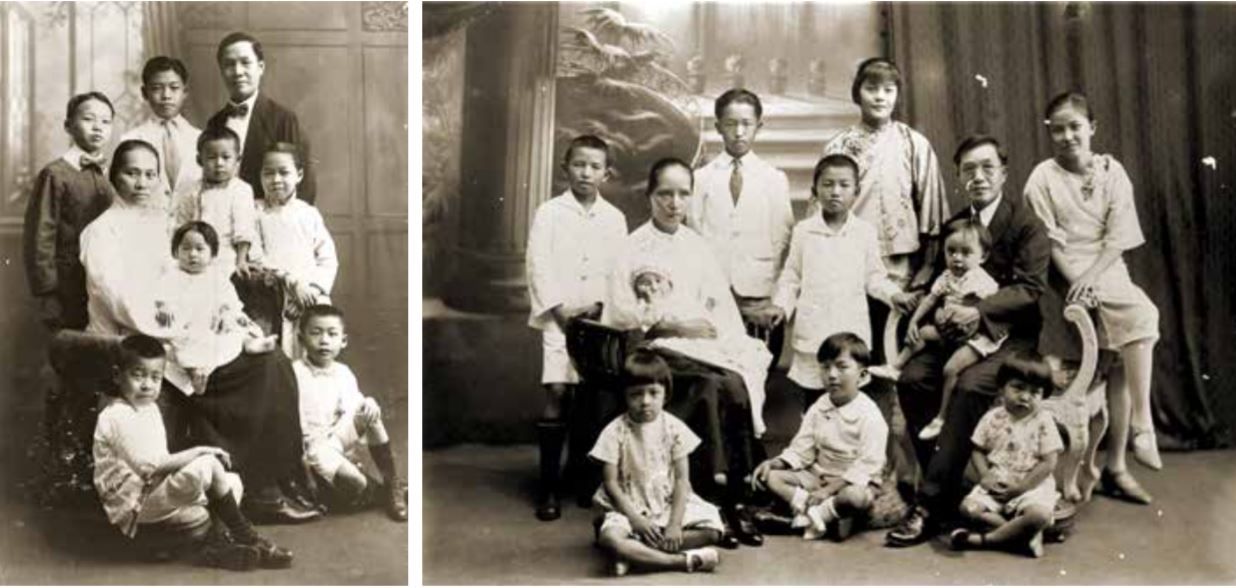

King Yan came to Singapore with his father in 1891 as an apprentice photographer. In 1897, he married Tong Oi Yuet in St Stephen’s Church in Hong Kong. They returned to Singapore and had 12 children. Three of his sons became photographers. A Methodist and an active YMCA member, King Yan was one of the first in Singapore to cut off his queue and was known in photographic circles as mo pin lou or “the man with no pigtail”.

On the eve of World War II, King Yan evacuated Eastern Studio because of vibrations to the shophouse structure caused by the frequent passing of heavy trucks along Stamford Road. He continued to operate Venus Studio in nearby Eu Court, a branch of Eastern Studio that he had opened in the 1930s. Unfortunately, these premises were damaged during a Japanese air raid, and the archive of negatives and prints destroyed. After the war, King Yan continued to work from his home at 26 Dublin Road. When he died in 1957 at age 80, his obituary in The Straits Times described him as “one of the pioneers of photography in the country” and the “grand old man of photography”.7

Poh Yan, who maintained an avid interest in new advances in photography throughout his life, married Soh Moo Hin in China in 1902 and they raised 13 children. Two sons became involved in photography. Lee Hin Ming, the eldest, ran the family-owned photographic supply company Wah Heng for many years and was also a founder and director of Rainbow Colour Service. Youngest son Francis Lee Wai Ming developed a keen interest in photography, kindled by watching his father in the darkroom, and bought his first camera with the profits made from taking identity card photos for fellow students at St Andrew’s School. He became a freelance photojournalist in the 1950s.

For many years, the business premises of Lee Brothers at Hill Street doubled as the family home and the older children were called upon to perform simple tasks in the studio. The ground floor was used mainly as storage. The first floor front room was the reception area with the living quarters behind. The top floor contained the studio and darkroom. At night, the reception area became the children’s bedroom as mats were unrolled and spread out on the floor. As the number of children increased, more living space was secured in a block of flats behind on Loke Yew Street.

When the Hill Street studio was acquired for redevelopment in the 1930s, Poh Yan moved to a smaller unit nearby at the corner of Hill Street and St Gregory’s Place. Business had, by this time, steadily declined due to the economic depression and the popularity of amateur photography. At the time of the move, three-quarters of the firm’s glass plate negatives had to be destroyed because of insufficient storage space.

With the imminent outbreak of World War II, Poh Yan permanently closed the studio. Although some family members continued to reside in the Hill Street shophouse, he and his wife moved to a farm at the eighth mile of Thomson Road. He passed away in 1960 at the age of 76.

The last of the family’s photographic enterprises to survive was Wah Heng and Co., importers of photographic materials at 95 North Bridge Road, of which King Yan, Poh Yan and their many cousins were shareholders. The firm stocked a “remarkable range of goods” for both beginners and experts in photography, and did business “throughout the Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States and the Dutch East Indies”.8

(Right) Lee Poh Yan (holding child on lap) with his wife and children, c.1930. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Studio Portraits

The Lee brothers were practitioners of a tradition that began with the invention of photography by Frenchman Louis Daguerre in 1839. The possibilities of studio portraiture were seized upon as the most exciting benefit of the new invention. The daguerreotype photographic method spread quickly and became available in Singapore by 1843 when G. Dutronquoy, proprietor of the London Hotel, placed an advertisement in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 4 December 1843, promising that a picture can be taken “in the astonishing short space of two minutes”, “free from all blemish” and “in every respect perfect likenesses”.9

In the 1860s, portrait photography was further invigorated by the introduction of the inexpensive carte-de-visite in France. Originally intended as a visiting card with a photographic portrait mounted on it, such cards were later produced in great numbers for friends’ albums.10 A further revolution took place not long after with the introduction of superior paper photographs made with the wet collodion process, or wet plate process. This new method gave a high-quality negative on glass with excellent resolution of detail from which an unlimited number of prints could be made.11

The commercial possibilities of the wet plate process were staggering. Any quantity of prints could be ordered from the best results of a studio session, and supplied at terms attractive to both photographer and customer. The first to exploit this technical advance in Singapore was Edward A. Edgerton who, in 1858, advertised his “photographic and stereoscopic portrait” services at his Stamford Street residence.12

Another early European photographer who established a photo studio in the settlement was John Thomson, who went on to become one of the most celebrated of all 19th-century photographers. He arrived in Singapore in 1862 equipped with the knowledge of the latest advances in commercial photography in Europe, and advertised a range of new services involving “micro-photographs”.13

Of all the European studios, however, the most enduring was G.R. Lambert & Co, which operated from the 1880s until around 1917. The official photographers to the King of Siam and Sultan of Johor as well as for major political events in Malaya, G.R. Lambert & Co maintained branch offices in Sumatra, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok. By the turn of the century, the firm had amassed one of the “finest collections of landscape views in the East, comprising about 3,000 subjects which were mainly purchased by globe-trotters as travel souvenirs and pasted into large leather-bound albums”.14

Chinese photographers were also active in Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as evidenced by the many examples of their work that have survived in family albums or turned up in antique shops. Such photographs are usually mounted on cardboard and carry names such as Pun Loon at High Street, Poh Wah at Upper Chin Chew Street, and Kwong Sun, Koon Hin and Guan Seng along South Bridge Road. While important examples of historic photography in their own right, the subjects are often posed stiffly and lack individual character.

In contrast, the Lee brothers achieved both subtlety and naturalness in their work. Their genius lay in their ability to combine the technician’s dispassionate skill with the camera, the scientist’s understanding of the subtleties of the darkroom and the artist’s finely developed sense of human character and human expression.

In many of the portraits found in the collection – all of which were taken circa 1910 to the mid-1920s – a dignity and timeless elegance is apparent, which tempts us to look upon the faces of those who climbed the steps to Lee Brothers Studio as though we might almost know them today.

All photos are from the Lee Brothers Studio Collection. Identities of the subjects are unknown as these photos are unrecorded excess or uncollected prints kept by the Lee Brothers Studio.

This is an abridged version of the introductory chapter by Gretchen Liu from the book, From the Family Album: Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio, Singapore 1910–1925, published by Landmark Books in collaboration with National Archives in 1995. The book is available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries. (Call nos.: SING 779.26095957 FRO and RSING 779.26095957 FRO)

NOTES

-

Family lineage records were kept by Dr Lee Ying Keng, the second son of Lee Tat Loon, who came to Singapore at the age of eight with his father. Lee Ying Keng attended Anglo-Chinese School and was 13 years old when his father died. He graduated from King Edward VII College of Medicine in 1920 and practised on board a coastal steamer plying the region until he set up practice in Muar, Johor, in the late 1920s. A copy of the family record was obtained courtesy of Marjorie Lau, daughter of Lee King Yan. See Oldest living graduate of a Singapore University? (1922, August 22). The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hillier, B. (1976, January 1). Victoria studio photographs (p. 17). London: Ash & Grant. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Turnbull, C. M. (1977). A history of Singapore, 1819–1975 (p. 97). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.57 TUR) ↩

-

Ong Ong Siang’s One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore was published in London 1923 and reprinted by Oxford University Press in 1967. An annotated edition was published by the National Library Board Singapore in 2016. See Song, O. S. (1923). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. London: John Murray. Retrieved from BooKSG; Song, O. S. (1967). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: University of Malaya Press. (RCLOS 959.57 SON); ); Song, O. S. (2020). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore: The annotated edition. Singapore: National Library Board Singapore. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Macmillan, A. (Ed.). (1923). Seaports of the Far East: Historical and descriptive commercial and industrial facts, figures & resources (p. 274). London: W. H. & L. Collingridge. (Call no.: RRARE 387.10959 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL 14242) ↩

-

The full obituary in The Straits Times on 31 December 1957 reads: “Mr Lee King Yan, 80, one of the pioneers of photography in the country died at his home in Serangoon Garden Estate yesterday. He came to Singapore from China 50 years ago. He had received numerous awards for his photography. He was the proprietor of the Eastern Photo Studio, Stamford Road. Often referred to as the ‘grand old man of photography’, Mr Lee leaves seven sons and four daughters.” See Colony’s grand old man of photography dies at 80. (1957, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 1 advertisements column 3: Notice: Mr Dutronquoy. (1843, December 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Carte-de-visits from old Singapore studios still turn up in antique shops in Singapore and London, with the name of the studio handsomely printed on the back. ↩

-

The most complete history of photography in Singapore to date is contained in Falconer, J. (1987). A vision of the past: A history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya: The photographs of G. R. Lambert & Co., 1880–1910. Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 779.995957 FAL) ↩

-

John Falconer contains 180 Lambert views and portraits of people and places in Singapore and Southeast Asia. ↩