Preserving Nan’an History in Singapore

The National Library recently received several rare items connected to the history of the Nan’an community and Hong San See Temple in Singapore. Ang Seow Leng presents highlights of the collection.

There are more than 1,000 Chinese temples in Singapore,1 some with roots that go back to the early years of the founding of modern Singapore in 1819. These temples are not only architecturally interesting, but also provide a window into the history of the early Chinese communities in Singapore.

One such temple is the Hong San See Temple (水廊头凤山寺;2 otherwise known as 凤山寺 or Temple on Phoenix Hill) on Mohamed Sultan Road – a place of worship for Hokkien immigrants from Nan’an (南安), or Lam Ann, county in southern Fujian province. Hong San See Temple – gazetted as a national monument on 10 November 1978 – is managed by Singapore Lam Ann Association (新加坡南安会馆), which was founded in 1924 by Nan’an immigrants.3

In March 2018, the clan association donated several rare historical materials to the National Library, with the intention of making these items available as primary research materials. The collection – which will be preserved for future generations of Singaporeans – mainly covers the history of the construction of the temple, and the association and its activities.

Early Nan’an Settlers

It is believed that Nan’an people were already living in Singapore when Raffles set foot on the island, although it is not known exactly when the first Nan’an immigrants arrived.

One concrete evidence is the discovery of the tombs of 31 anonymous Nan’an pioneers who were buried at Qing Shan Ting burial ground4 (青山亭) in 1829. The graves were dug up and moved four times due to urban redevelopment until the remains were eventually cremated and laid to rest at Bukit Panjang Hokkien Public Cemetery. On 18 November 1977, the Singapore Lam Ann Association erected a stele on its premises adjacent to the Hong San See Temple to commemorate the first Nan’an settlers on the island.5

(Right) The stele erected by the Singapore Lam Ann Association on its premises to commemorate the 31 anonymous Nan’an natives who were already living in Singapore when Stamford Raffles arrived in 1819. Little Red Dot Collection. All rights reserved, National Library Board, 2009

It is estimated that there are close to 400,000 Nan’an descendants in Singapore today,6 including Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Grace Fu, Member of Parliament Denise Phua and the acclaimed artist Tan Swie Hian.7

History of Hong San See Temple

In 1836, a group of Nan’an pioneers led by Liang Renkui (梁壬葵) established the original Hong San See Temple on Tras Street.8 In an article to Xing Bao (星报) newspaper in 1893, prominent Straits Chinese writer Chen Shengtang (陈省堂) noted that the temple was popular among devotees because the main temple deity, Guang Ze Zun Wang (广泽尊王), or Lord of Filial Piety, answered their prayers.9

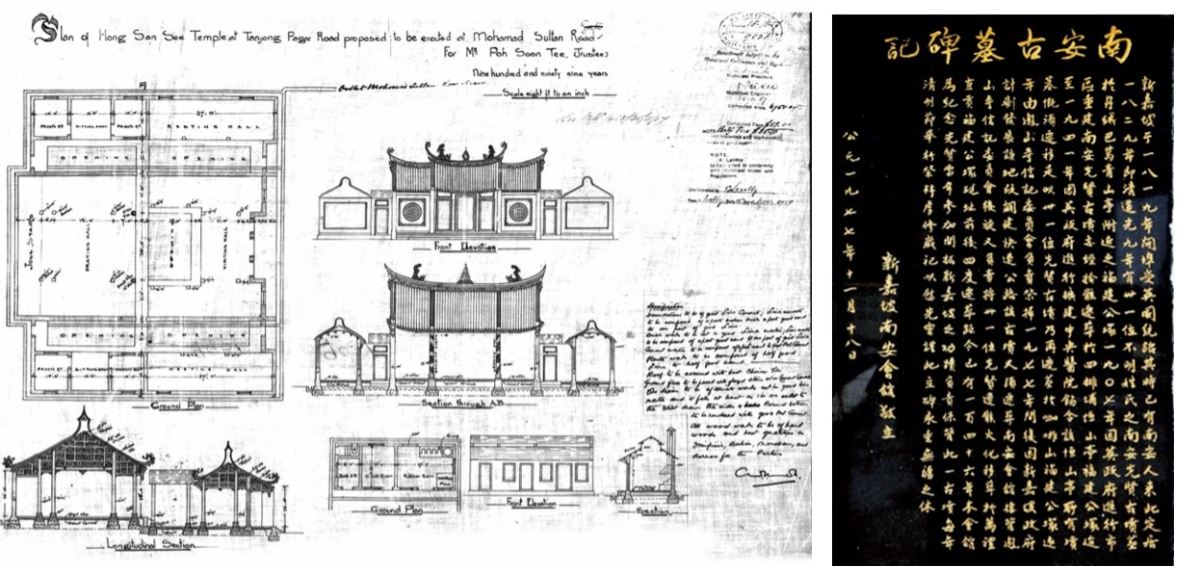

In 1907, the colonial government acquired the temple land for a road widening project10 and paid 50,000 Straits dollars as compensation. The Nan’an builder and architect Lim Loh (林路)11 – the father of World War II hero Lim Bo Seng (林谋盛) and director of the temple’s management committee – subsequently purchased a plot of land at Mohamed Sultan Road for a new temple.12

The construction took almost five years between 1908 and 1913, and cost 56,000 Straits dollars.13 In addition to its role as a place of worship, Hong San See Temple also addressed the demand for education by establishing Nan Ming School (南明学校) on the temple grounds in 1914. The school operated for 10 years until dwindling enrolment led to its closure.

One of the earliest descriptions of the temple at Mohamed Sultan Road can be found in the 1951 book, 新加坡庙宇概览 (An Overview of the Temples in Singapore), in which the author describes the picturesque sea view and surrounding houses. From the temple, one could see Fort Canning and Mount Faber, making it Singapore’s only temple with a panoramic view at the time.14

The temple was built in the southern Fujian architectural style and features two beautiful granite columns carved with entwined dragons at the entrance, dragon ornaments on the roof made of cut porcelain (剪瓷雕) and intricate carvings on the facade depicting scenes and characters from Chinese classics such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms.15

In 1936, a row erupted over the ownership of the temple, leading to a legal suit. The property eventually came under the Hong San See Temple Trustee Committee before it was relinquished to the Singapore Lam Ann Association in 1973.16

Between 2006 and 2009, the temple underwent a $3-million restoration project spearheaded by the Lam Ann Association and funded by clan members, temple devotees and the Lee Foundation. The restoration was so well executed that in 2010, Hong San See Temple became the first building in Singapore to receive the Award of Excellence in the UNESCO Asia- Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.17

Highlights of the Donations

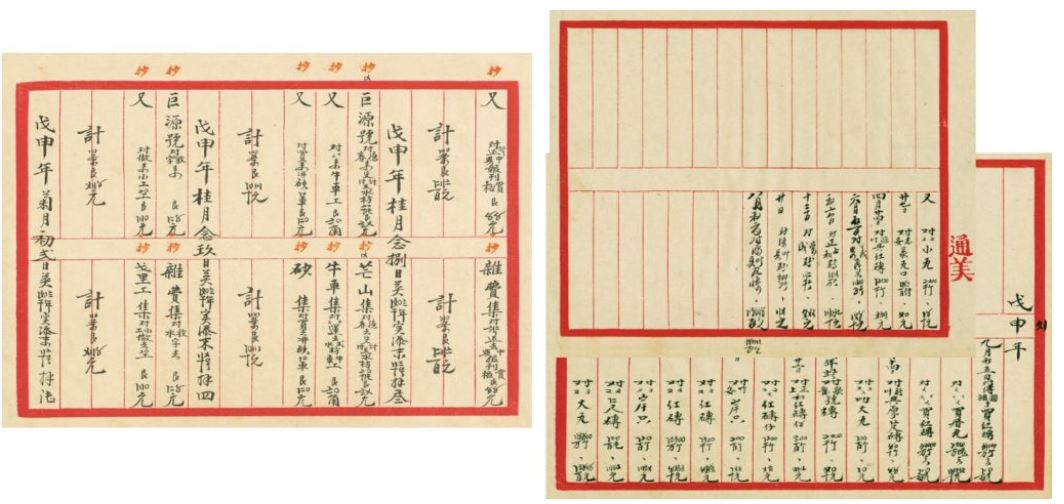

Among the items that the Lam Ann Association donated to the National Library are its rules and regulations document from 1950, minutes of clan meetings (1924–35), documents relating to the exhumation of the remains of civilians killed during the Japanese Occupation, marriage certificates issued by the association (1935–60), and a set of seven accounts books pertaining to the construction of the Hong San See Temple, including names of the craftsmen involved and the cost as well as types of building materials.

During the restoration of the temple between 2006 and 2009, these accounts books provided crucial information that helped resolve differences in opinion among various project consultants with regard to the colour of the original tiles used in the eaves. For instance, one of the entries in volume 2 revealed that green glazed eave tiles were purchased in the Wu-shen (戊申) year (1908) during the construction of the temple.18

In an article published in Lianhe Zaobao Weekly on 1 April 2018,19 independent Chinese history researcher Kua Bak Lim pointed out that the dates recorded in the association’s accounts books – the earliest of which is from 1907 – reflect the Gregorian and Chinese Lunar calendars as well as the Chinese era name of the reigning emperor, hinting at the political changes taking place in China at the time, especially between the years 1910 and 1911 when the Qing dynasty was overthrown. Interestingly, Suzhou numerals, in which special symbols to represent digits instead of Chinese characters for accounting and bookkeeping purposes, were used in these books.

Kua also noted that names of companies and banks listed in the accounts books provide a snapshot of the Chinese commercial firms operating in Singapore in the early 20th century.

(Right) The accounts books include names of the craftsmen and details of the cost of building the temple as well as types of building materials used. One of the entries in volume 2 indicates that green glazed eave tiles were purchased in the Wu-shen (戊申) year (1908) during the construction of the temple. Such information proved invaluable for architects involved in the restoration work. Images reproduced from 凤山寺总簿:大清光绪叁拾叁年岁次丁未孟冬月立 (Vol. 2; pp. 185–186).

The donation by the Singapore Lam Ann Association is especially significant given that most of the records belonging to the association and Hong San See Temple were destroyed during World War II.20 Whatever of historical value that has been salvaged is now kept in the holdings of the National Library and will be preserved for posterity. Most of the items will be digitized by the library in due course and made available for online access.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services related to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services related to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Zaccheus, M. (2016, November 20). Nuggets of Singapore history, from inscriptions. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

水廊头风山寺 (Shui Lang Tou Feng Shan Si) is the name given to the temple to differentiate it from other temples in Singapore that are also called Hong San See. 水廊头refers to a well that used to exist at Mohamed Sultan Road in the early 20th century. It was the main source of water for the villagers living in the area at the time. The use of this name was believed to have started in 1905, according to an inscription found at the 水廊头大伯公庙 (Shui Lang Tou Da Bo Gong Miao), a Tua Pek Kong temple. See 林文川. (2003, October 5). 本地多家寺庙取名“风山寺”. 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], p. 6; 新加坡地名趣谈. (1991, February 10). 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (1992). Hong San See preservation guidelines (Vol. 1, p. 4). Singapore: Preservation of Monuments Board. (Call no.: RSING 363.69095957 HON); Colony of Singapore. Government gazette. (1951, June 15). List of existing societies registered in the Colony of Singapore (p. 934). Singapore: [s.n.] (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SGG). ↩

-

Qing Shan Ting, at the junction of South Bridge Road and Tanjong Pagar Road, is one of the earliest Chinese burial grounds. See Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment (p. 285). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO) ↩

-

Dean, K., & Hue, G.T. (2017). Chinese epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911 (Vol. 1, pp. 414–415, 433–434). Singapore: NUS Press; Guilin City: Guangxi Normal University. (Call no.: RSING 495.111 DEA). ↩

-

Sim, W. (2014, November 21). Clan group gives almost $1m to centre. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sim, W. (2014, November 20). PM Lee pays tribute to people from Lam Ann county in Fujian; clan group donates $880,000. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

南安会馆前身: 凤山寺170春秋话从头. (2006, September). 南安会讯 = The Lam Ann bulletin, 17, p. 3. 新加坡: 新加坡南安会馆. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.25957 LAB); 郭志阳 & 郭志阳主编 [Lam Ann Association (Singapore)]. (2006). 新加坡南安会馆80周年纪念特刊, 1926–2006 = Singapore Lam Ann Association 80th anniversary souvenir magazine (p. 65). 新加坡: 新加坡南安会馆. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.2597 SIN). ↩

-

黄慧敏. (2016, July 7). 海门奇葩 峇峇社群三语文学. 联合早报. Retrieved from Zaobao website; Dean & Hue, 2017, vol. 1, p. 434; 陈省堂. (1893, December 16). 游凤山寺记. 星报, p. 5. Retrieved from National University of Singapore website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore), 1992, vol. 1, p. 5. ↩

-

Lim Loh, who was also known as Lim Chee Gee (林志义) and Lim Hoon Leong (林云龙), made his fortune during pre-war Singapore from rubber estates, brick and biscuit factories, and the trading and construction businesses. He was involved in the building of Goodwood Park Hotel and Victoria Memorial Hall, and also designed and built Hong San See Temple. See Tan, T. (2008, August 14). Rare gift for SAM. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

郭志阳 & 郭志阳主编, 2006, p. 65; Dean & Hue, 2017, vol. 1, p. 434. ↩

-

Dean & Hue, 2017, vol. 1, pp. 406,434. ↩

-

新加坡庙宇概览. (1951). (p. 37). 新加坡: 南风商业出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RDTYS 294.3435 CHI) ↩

-

新加坡凤山寺 = Singapore Hong San See Temple. (2007). (p. 38). 新加坡古迹保存局: 新加坡凤山寺国家古迹重修委员会. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 203.5095957 SIN); Lin, W.J. (2010, September 25). Hong San See in its glory. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

黄奕欢. 新加坡凤山寺史话 – 附述归属南安会馆经过. 新加坡南安会馆. (1977). 新加坡南安会馆金禧纪念特刊, 1977 (p. 7). 新加坡: 新加坡南安会馆. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 369.25957 LAM); 新加坡南安会馆, 1977, p. 7. ↩

-

Yen, F. (2010, September 19). The little temple that could. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. The Straits Times, 25 Sep 2010, p. 8. ↩

-

2010联合国亚太文化资产保存卓越奖授奖典礼特辑编委会. (2010). 新加坡凤山寺: 荣膺2010联合国亚太文化资产保存卓越奖授奖典礼 = Singapore Hong San See Temple awarded 2010 UNESCO Asia Pacific Heritage awards for culture heritage conservation (p. 10). 新加坡: 新加坡南安会馆. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 203.5095957 SIN) ↩

-

柯木林. (2018, April 1). 南安会馆捐献凤山寺文物 老账簿会说话. 联合早报周刊. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2018, March 3). Temple’s rare historical records donated to NLB. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩