Revulsion and Reverence: Crocodiles in Singapore

Crocodiles elicit fear and respect by turns – and occasionally, even indifference. Kate Pocklington and Siddharta Perez document reptilian encounters at specific times in Singapore’s history and their impact on the human psyche.

On 6 November 2017, the National Sailing Centre suspended all water-based activities in the sea off East Coast Park for four days after an estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) – also known as the saltwater crocodile – was spotted in the waters there.1 This was one of five reported crocodile sightings in 2017, drawing both media and public attention to this elusive reptile that inhabits the rivers, reservoirs and seas around Singapore.2

Crocodiles have always been native to Singapore, but their numbers have dropped drastically due to unbridled hunting as well as destruction of their natural habitats throughout Singapore’s modern history. In their search for new habitats, these reptiles have often strayed into urban areas.

One of the early documented crocodile encounters in a public space took place in 1906 at the Swimming Club at Tanjong Katong. The reptile was seen sunning itself on the club’s diving platform when someone took a shot at the creature, prompting it to flee in haste.3 The most recent recorded sighting to cause a media flurry occurred in January 2018 at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, where a crocodile was seen basking under the sun on a path cutting through the forest.4

In colonial times, crocodiles were often caught and taken to police stations as bounty.5 These days, however, the Public Utilities Board is more likely to receive calls from an anxious member of the public whenever crocodile sightings occur in water bodies or outside the perimeters of public spaces under the purview of the National Parks Board. The Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES) too receives its share of calls to assist in the rescue and relocation of wildlife that have strayed into public spaces.

Reptilian Encounters

Not surprisingly, sightings of crocodiles in urban Singapore are treated as freak occurrences. Mistaken identity aside,6 media reports of crocodile sightings raise alarm and strike fear in people’s hearts about the invasion of such large reptiles into public recreational spaces.

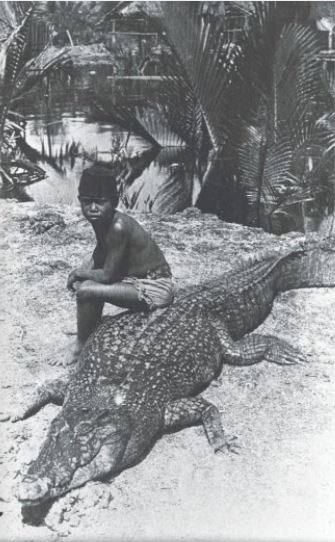

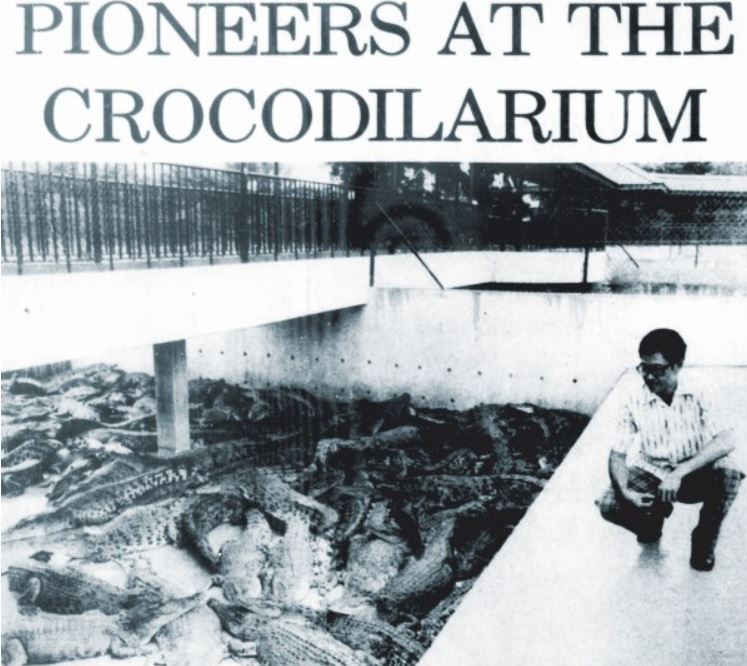

Such sensational media reporting is based on the premise that people are more comfortable appreciating crocodiles from a safe distance – confined in public spaces such as zoos and farms.7 Those who grew up in the 1980s and 90s would remember two such attractions that promised the thrill of being “up close and personal” with crocodiles.

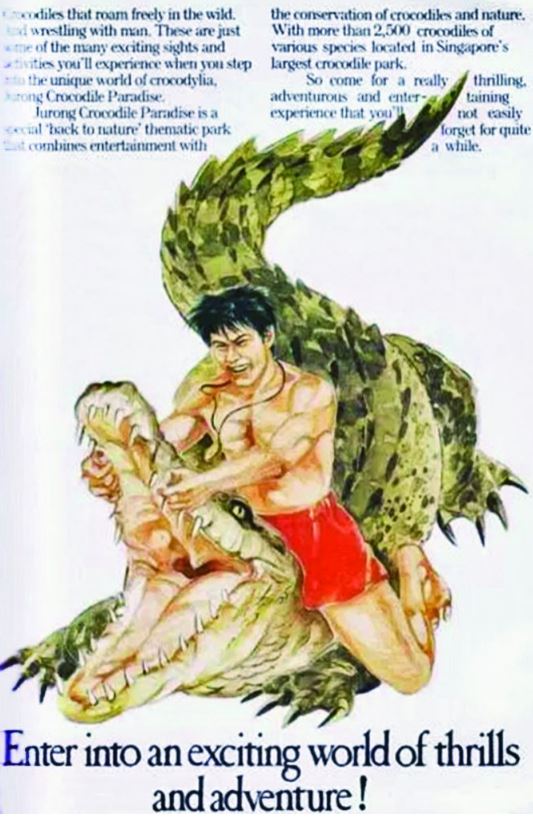

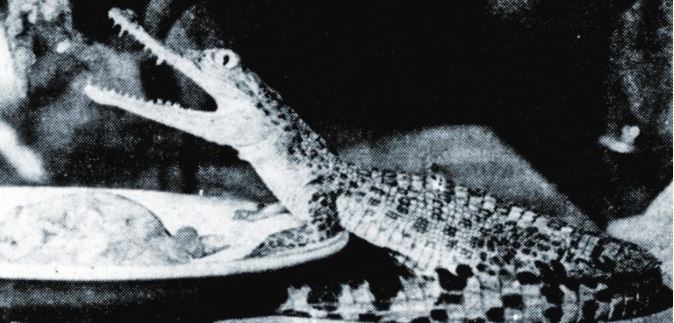

The Singapore Crocodilarium at East Coast Parkway and Jurong Reptile and Crocodile Paradise, which opened in 1981 and 1988 respectively, bred crocodiles and staged performances that attracted large crowds. Stuntmen would risk life and limb as they wrestled with the reptiles as a form of entertainment.8

In 1989, Winoto, the chief trainer at the Jurong Reptile and Crocodile Paradise, had part of his left cheek torn off by a female crocodile named after the American wrestler Hulk Hogan. Winoto survived the attack but ended up with 10 stitches on his face.9 The two parks closed in the early 2000s due to dwindling visitor numbers, and as other, more contemporary, attractions in Singapore took their place.10

Nevertheless, the island continues to host crocodiles in the wild, approximately 20 are known to be residents of the mangrove habitats of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. Today, with over 90 percent of Singapore’s mangrove ecosystem destroyed, the reserve encompasses the largest mangrove forest – at 1.17 sq km11 – left on the island.

Although Sungei Buloh’s mangrove forest makes up a mere 1.5 percent of the country’s original mangrove mass, it remains, by default, the preferred habitat of the crocodile. Urban encroachment on mangrove areas has literally squeezed the population of crocodiles into the Johor Straits, and subsequently, into this tiny patch of wetland reserve in the remote northwest of the island.

In 2010, it was reported that “these [mangrove] patches have regenerated well as they are generally isolated from intrusive anthropogenic influences”12 – in other words, relatively free from human intrusion. Such stable environments provide for a healthy ecosystem where a natural equilibrium is maintained and supports a biodiversity that includes crocodiles in their natural environment.

The tussle for space in land-scarce Singapore for urban development and nature represents just the tip of the iceberg in understanding how humans co-exist with crocodiles in Singapore. Sightings of crocodiles may elicit fear, shock, surprise, amusement or even indifference whenever they are reported in the media.

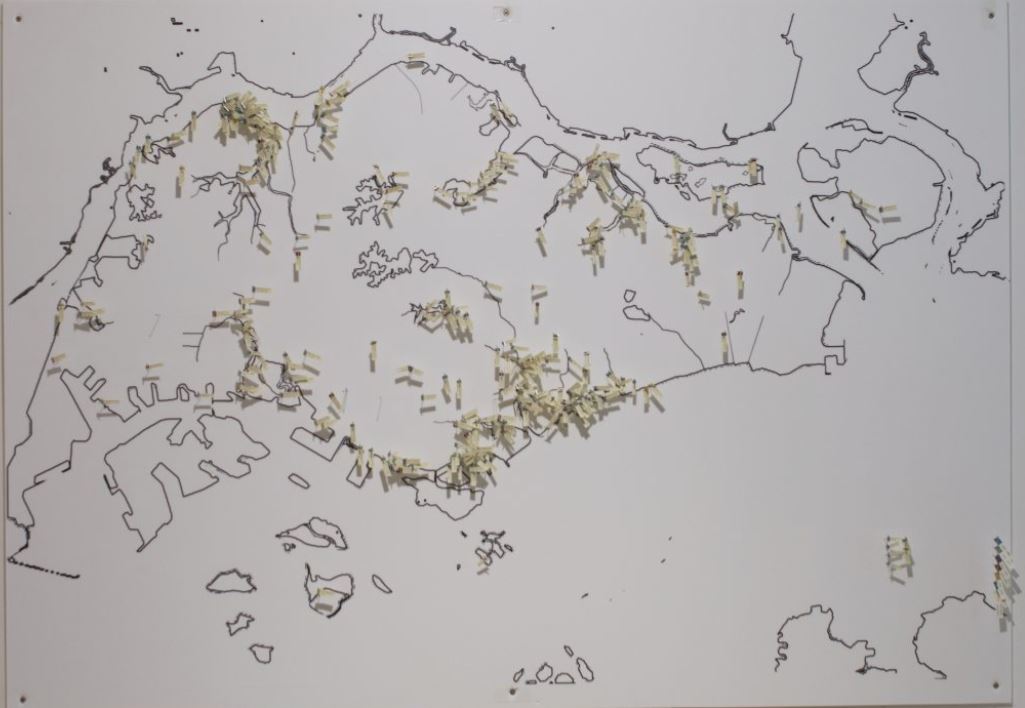

Using specific time periods such as 1960 and 1977 as markers, the empirical collection and study of data for the research project Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth threw up interesting findings. The project revealed different reactions to the crocodile that are intertwined and layered with the cultures and experiences of different communities throughout time and history in Singapore.

Launched in October 2016, Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth is a research project held in the “prep-room” of NUS Museum. Revolving around ideas of the estuarine crocodile in Singapore, the project provides a platform for presentations of research projects and interpretations by professionals in the fields of natural history, arts and cultural studies.

The Buaya project is part of natural history conservator Kate Pocklington’s on-going research into the estuarine crocodile in Singapore, prompted by her conservation of a century-old specimen for permanent display at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum in 2013.

The Buaya project maps over 380 present and historic records of crocodiles in Singapore in response to the 1996 International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) report which assessed these animals to be “regionally extinct” in Singapore.

1960: The Year of the Crocodile

In the post-colonial years, with Singapore facing an uncertain future, people living in some parts of the island were faced with the presence of crocodiles. The range of emotions and reactions these crocodile sightings elicited in people is quite fascinating.

In 1960, 31-year-old clerk Chew Kok Lee, along with a group of fishermen from a nearby village, carried out an all-night vigil in Punggol to hunt down a 20- to 25-foot-long crocodile that had been terrorising fishermen in the area for some time.13

Fifteen-year-old Goh Koon Seng recounted that he was wading out to sea to help his father haul in the day’s catch when he spotted something sinister in the water:

“A long black thing surfaced. I did not pay much attention at first. I thought it was a log. There are so many floating around here. Then its mouth opened. I screamed and turned back. As I got out of the water I heard a splash, looked back and saw the crocodile’s tail submerging.”14

Although Chew and his band of hunters managed to fire their shotguns at the reptile, these could have merely “just tickled it” because the same crocodile returned a week later with his mate in tow; the latter “about 25 feet long and weighing about 600 lb” but white in colour, according to one eyewitness.15

Meanwhile, that same year, in Sungei Kadut in the north of Singapore, a live 20-foot-long crocodile was viewed in a completely different light by residents of the area: here the villagers regarded the crocodile as sacred, revering it as a kramat.16 This particular reptile was covered in barnacles and regularly basked on a sand bank. Fishermen would say a silent prayer whenever they spotted the creature.

Residents were so protective of the creature that they would not disclose its location to anyone, believing that harm would befall the fishermen if the sacred crocodile moved to another site. Teo Boon Chin, who had lived in the area for over 20 years, indicated the area where the crocodile made its home with “a sweep of his arm” when he was interviewed by a newspaper in March 1960. “We know the home of the kramat, but are not supposed to tell it to anyone”, he cautioned.

Another villager in Sungei Kadut by the name of Ah Lim, who had seen the crocodile “float on the river or laze about in the nearby mangrove swamp”, added, “It is the guardian of our river and the protector of our fishermen.”17

In the same year, on the southern shore of the island, villagers in Berlayer Creek in Pasir Panjang dealt with the presence of crocodiles “some of which four to five feet long” in the canal in quite the opposite manner: they held a feast in honour of their local kramat and invited a pawang (medicine man) to “scare away” the crocodiles infesting the river.18 Che Zainai Kubor, one of the villagers said, “It is not possible for human beings to stop crocodile breeding, but probably our kramat can.”

These crocodile encounters evoked reactions in people ranging from bravado to reverence and respect, and fear. But there were also some who regarded the existence of crocodiles with complete indifference.

In August 1960, for instance, a crocodile suspected of escaping from a crocodile farm in Serangoon Garden Estate made itself at home in an unused water hyacinth pond at nearby Vaughan Road. The creature was described as having a tendency to submerge itself whenever people looked at it. When a newspaper headline in The Singapore Free Press pronounced that a “Shy croc in flower pond spreads fear among kampong folk”, a long-time resident in the area, Lim Poon Guan, said, matter-of-factly, that finding “a crocodile in a pond here” came as no surprise to him at all.19

Early Records of the Crocodile

Crocodile records in Singapore go back to the early days of its colonial history. The earliest documented encounter of a crocodile in Singapore is found in the autobiography of Malacca-born Munshi Abdullah, who was employed by Stamford Raffles as a scribe and interpreter. Hikayat Abdullah, published in 1849, documents an incident about William Farquhar when he was Resident of Singapore between 1819 and 1823.

Farquhar’s dog had playfully waded into the “Rochore River” when it was suddenly seized by a gigantic crocodile measuring at least “3 fathoms” (5.5 metres). In anger, Farquhar ordered for the river to be barricaded and the crocodile speared to death. Its carcass was later hung on a fig tree by the “Beras Basah River” for all to see.20

Although Munshi Abdullah claimed that the attack on Farquhar’s dog was the first time people knew of crocodiles in Singapore, a text predating the Hikayat Abdullah disputes this.

One of the accounts in Hikayat Hang Tuah, a Malay text written between 1641 and 1739, tells the story of the legendary white crocodile and the Raja of Malacca. One day, the raja, or king, was on board his vessel bound for Singapore when his crown fell into the sea. When he asked for the crown to be salvaged from the water, none of his men stepped forward, knowing full well that the Straits of Singapura (the Straits of Johor today) was “infested with man-eating crocodiles”.

A high-ranking Laksamana (or admiral), most likely Hang Tuah himself, courageously stepped forward to carry out the raja’s bidding. Valiantly, he dove into the water to retrieve the crown, but when he resurfaced, a white crocodile appeared and clamped its jaws onto his keris, a traditional bladed weapon that is said to be imbued with spirits and energies.

In the ensuing struggle with the crocodile, the raja’s crown slipped from the Laksamana’s grasp. He managed to grab the tail of the crocodile, but was pulled deeper underwater, forcing him to let go of the reptile. Although the Laksamana’s precious keris was lost, the crown, fortunately, was safely retrieved. Perceiving this entire incident as an ill omen, the raja ordered his fleet of ships to turn back to Malacca at once.21

Of DOGS AND CROCS

William Farquhar’s dog was not the only casualty that fell prey to crocodiles. In August 1907, people who had mysteriously lost their pet dogs in the “past few years” were told to contact the taxidermist at Middle Road to ascertain whether four dog collars retrieved from the stomach of a crocodile shot in the Punggol River belonged to them. The carcass was being prepared to be sent to England when the discovery was made.

REFERENCE

Discovery in a crocodile’s stomach. (1907, August 13). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

1977: The Year of the White Crocodile

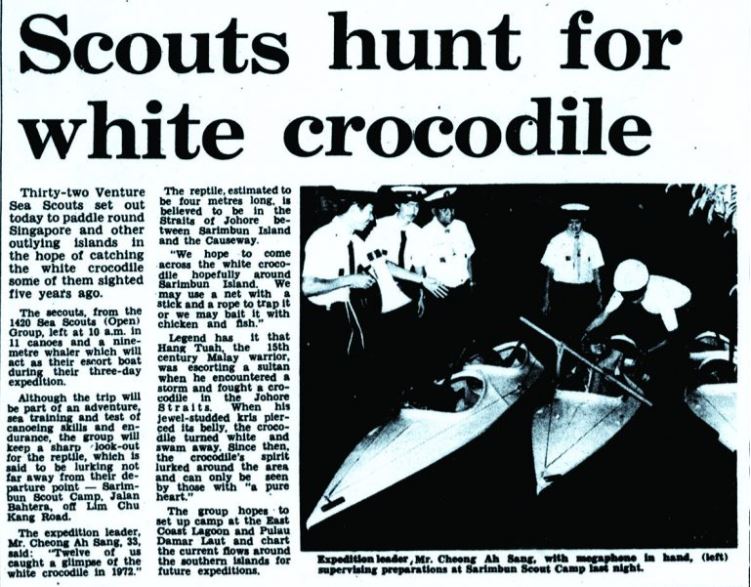

In 1977, a group of plucky Venture Sea Scouts set out to capture a white crocodile22 that was said to inhabit Pulau Sarimbun in the northwest coast of Singapore. Newspaper reports on this expedition were published on 2 May, 30 April, 13 June and 25 June 1977.23

These scouts were following up on an unrecorded sighting of a white crocodile by another group of Venture Sea Scouts five years earlier.24 Recalling the incident, Cheong Ah Sang said that his group of 12 scouts had “caught a glimpse of the white crocodile in 1972”. Determined to trap it, he decided to lead a team of 32 scouts on a quest to search for the reportedly 13-foot-long reptile.

On 30 April 1977, The New Nation reported that Cheong’s group embarked on a three-day expedition using 11 canoes and were escorted by a nine-metre whaler. He told the reporter:

“We hope to come across the white crocodile hopefully around Sarimbun Island. We may use a net with a stick and a rope to trap it or we may bait it with chicken and fish.”25

In venturing into the waters of the Straits of Johor where Pulau Sarimbun is located, these young adventurers were returning full circle to the historic Hang Tuah’s encounter with the white crocodile. Cheong’s expedition, however, failed in its bid to capture the crocodile.

According to the Hikayat Hang Tuah, “only the pure of heart can see the white crocodile”. Taking this advice to heart, another group of scouts led by Paul Wee prepared for the hunt by vowing to fast and refrain from consuming pork. They had earlier revealed their intention to donate the captured animal to the zoo. However, after two failed attempts, the scouts were ordered to call off the hunt by the Chief Commissioner’s Office.26

PET CROCS

Interestingly, crocodiles were also kept as pets or bred in the backyard of houses in Singapore. In 1948, it was possible to buy a live baby crocodile for as little as 25 to 40 Malayan dollars, and if the customer so desired, have the reptile killed and skinned, and made into a pair of custom-made shoes.27

Keeping crocodiles as pets could sometimes lead to peculiar and troublesome consequences.

In 1899, a 70-yard “menagerie race” took place in which a “young crocodile driven by Captain Lucy” competed against a goose, a goat, a monkey and two donkeys (the crocodile did not win the race).28

In the late 1800s, the pet crocodile of a Captain Gamble that became too big as an adult was released into the Botanic Gardens Lake only to later bite one of the gardeners. In order to capture the crocodile, the lake had to be drained and poisoned with tuba roots, unfortunately killing every living thing residing in the waters. The crocodile, however, was nowhere to be found, the creature having presumably left the confines of the freshwater lake.29

The Crocodile Lives On

Leaving the sightings of the elusive white crocodile aside, it is worth examining early maps of Singapore and drawing logical connections between the names of the surrounding islands and their geography.30 Place names can be a useful key in identifying local terrain, and can indicate the presence of certain species of animals.

The names Pulau Buaya (near Jurong Island) and Alligator Island (Pulau Pawai today), which appear off the southwestern coast of Singapore on maps dating back to the early 1800s, suggest the presence of crocodile populations (as well as abundant mangrove habitats) at some point in the islands’ history. These indicators, along with references in the Hikayat Hang Tuah, imply that from north to south, Singapore was once home to a sizeable population of crocodiles.

While the white crocodile remains an elusive mystery, there is a local lore about such a creature appearing in the Kallang River every 20 years. Although no actual encounters of white crocodiles have been recorded at the river, the reptile still looms large in the public imagination.

News reports and public records on crocodile sightings in Singapore over the last 200 years have enabled us to pinpoint the physical locations of these reptiles on the island as well as track encounters that have taken place between crocodiles and humans.

The idea of “public space” is frequently challenged in the various encounters between humans and crocodiles in this article. The natural human tendency is to react negatively, from shutting down activities in parks and water-based clubs to draining and poisoning lakes.

The public spaces developed for encounters with crocodiles question the notion of for whom or for what they were controlled for – zoos and marine parks are regulated spaces that allow encounters (or “non-encounters” in reality) with crocodiles within a safe setting for humans, while reserves are spaces controlled for the mobility of wildlife. Yet, the making of these spaces is constantly reconfigured when crocodile sightings take place. In the myriad encounters with these reptiles, whether from actual documentation or from cultural memory, the crocodile’s existence still escapes being understood in public history.

Siddharta Perez is a Curator at NUS Museum. Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth is one of the prep-room research projects she is currently managing.

Siddharta Perez is a Curator at NUS Museum. Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth is one of the prep-room research projects she is currently managing.

Kate Pocklington is a Conservator at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. She heads the collaborative research project, Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth, at NUS Museum.

Kate Pocklington is a Conservator at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. She heads the collaborative research project, Buaya: The Making of a Non-Myth, at NUS Museum.

NOTES

-

Lim, M.Z. (2017, November 9). Water training will resume on Friday, with no further crocodile sightings: S’pore Sailing Federation. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Lee, M.K. (2017, August 24). Warning signs put up at Changi Beach Park after crocodile sighting. The Straits Times; Tan, A. (2017, August 8). Crocodiles spotted in north-eastern Singapore. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. [Note: One of these sightings involved the death of a 1.5-metre-long crocodile which was hit by a car at Kranji. See Wild crocodile dies from injuries after accident along Kranji Way. (2017, June 6). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website.] ↩

-

A “croc” at the swimming club. (1906, May 15). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lam, L. (2018, January 22). NParks to extend barricade to pathway where crocodile was spotted at Sungei Buloh. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Untitled. (1856, December 16). The Straits Times, p. 5; Thursday, 25th August. (1870, August 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

When seen from afar, monitor lizards have been mistaken as crocodiles due to their similar shape and colouration. Unlike monitor lizards, crocodiles do not have a forked tongue. See It was just a harmless lizard… (1957, January 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Richards, A. (1960, April 6). Flirting with danger in croc farm. The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 10 Advertisements Column 1. (1981, March 22). The Straits Times, p. 10; Chia, M. (1988, September 4). Croc park to open soon in Jurong. The Straits Times, p. 12; Goh, K. (1988, December 15). A big bite of the business. The New Paper, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, S. (1989, March 7). Croc bites trainer during show. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Paradise lost. (2007, January 26). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yee, A.T.K., et al. (2010, June 4). The present extent of mangrove forests in Singapore. Nature in Singapore, 3, 139–145. Retrieved from Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum website. ↩

-

Yee, et.al, 4 Jun 2010. ↩

-

Clerk keeps all-night vigil at creek for a 20-ft. crocodile. (1960, March 17). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Croc scares fishermen. (1960, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 18 Mar 1960, p. 16; Ponggol croc returns with a mate. (1960, March 26). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kramat, or keramat, from Arabic karama, translated as “miracle”. Whilst often deemed as a material shrine, kramat is not exclusive to a physical space nor spiritual entity, but a complex sacred “shrine” to both, visible and invisible, and applied to the mobile or immobile physicality of a spirit. ↩

-

They offer a silent prayer to ‘sacred’ crocodile. (1960, April 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Richards, A. (1960, June 29). Villagers to hold a feast for kramat to scare away crocs in the canal. The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Shy croc in a flower pond spreads fear among kampong folk. (1960, August 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir. (1918). The autobiography of Munshi Abdullah (W.G. Shellabear, Trans). Singapore: Printed at the Methodist Pub. House. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Kassim Ahmad. (2010). The epic of Hang Tuah. Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA 398.2209595 HIK) ↩

-

This incident in 1977 gives room for speculation. Were the scouts searching for what they thought was the mythical white crocodile? Or were they looking for a crocodile that was possibly afflicted by a rare biological condition? One such condition could be albinism, a congenital disorder characterised by the absence of natural pigment, causing even the eyes to be of a different colour. Another cause could be hypomelanism – a reduced amount of melanin. In snakes that are affected by this condition, some coloured parts (mostly black) of their bodies are retained. There is also leucism, which is a partial loss of pigmentation that causes part or all of the crocodile to be white. ↩

-

Scouts hope to bag white croc. (1977, May 2). The Straits Times, p. 5; Scouts hunt for white crocodile. (1977, April 30). New Nation, p. 2; Another hunt by scouts for white croc. (1977, June 13). The Straits Times, p. 8; Tan, B. (1977, June 25). A fourth bid to catch the white croc. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Nation, 30 Apr 1977, p. 2. ↩

-

New Nation, 30 Apr 1977, p. 2. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Jun 1977, p. 8; The Straits Times, 25 Jun 1977, p. 12. ↩

-

The Malayan dollar was used from 1939 to 1953 in Brunei and Malaya (under British colony and protectorate). Shoes made of lizard skin were also popular. See Choose your own crocodile. (1948, May 2). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gymkhana meeting. (1889, September 4). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Gardens crocodile. (1892, January 23). The Straits Times, p. 2; The hunting of the crocodile. (1892, January 27). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: Before this incident, crocodiles were kept at the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Today, the Marsh Gardens has a signboard informing visitors how it was “once the location of a rhinoceros wallow and alligator [sic. crocodile] ponds when the Singapore Botanic Gardens had a zoological collection in the 1870s”.] ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore. (1839). Map of the Island of Singapore and its Dependencies [Topographic Map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩