The Istana Turns 150

The resplendent Istana – where colonial governors and modern-day presidents once lived – celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2019. Wong Sher Maine recounts key moments in its history.

“The building is a handsome one – the handsomest by a long way in the Settlement and one which will be an ornament to the place long after those who fought for and against it have passed away.”1

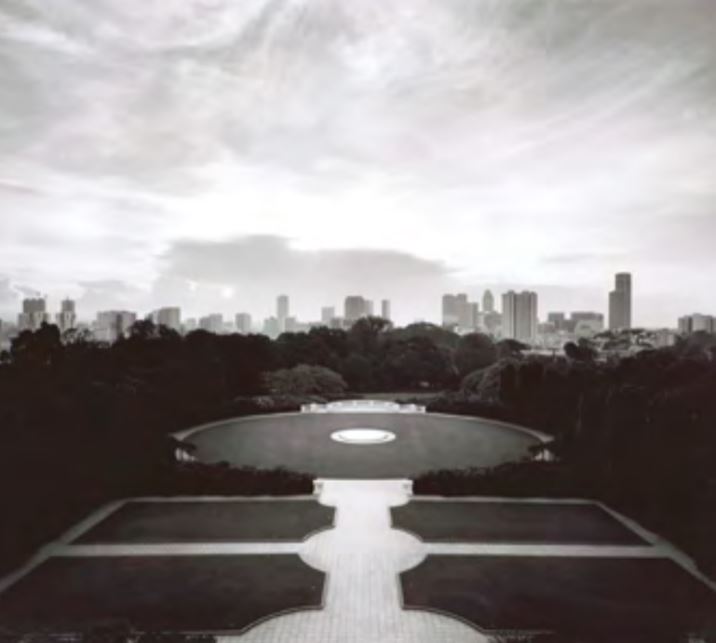

These words by a Straits Times scribe some 150 years ago would prove to be uncannily prophetic. He was referring to Government House, which is today known as the Istana, the official residence and office of the president of Singapore. A century-and-a-half old, the Istana – which means “palace” in Malay – is a gazetted national monument and also functions as the working office of the prime minister of Singapore. It is the closest thing Singapore has to Buckingham Palace or the White House.

Colonial Beginnings

Government House was originally built by the British colonial government to serve as the residence of the governor of the Straits Settlements and later the governor of the Colony of Singapore.2 For about 40 years after Stamford Raffles landed in 1819, the early governors (initially known as Residents)3 lived in a wooden house on Government Hill4 (now Fort Canning). However, when the house was demolished in 1859 to make way for a fort, another home had to be found for the governor.

A 106-acre (0.4 sq km) plot of land was identified as an alternative. It was part of the former nutmeg plantation owned by the East India Company barrister Charles Robert Prinsep, after whom Prinsep Street is named. The plantation had been devastated by a disease that killed off all the nutmeg trees in the mid-1850s in Singapore.5 The land was on elevated ground and provided superb views of the town and harbour.

Government House was built on the instructions of Harry St George Ord, then governor of the Straits Settlements (1867–73). The appointed architect was Colonial Engineer Major John Frederick Adolphus McNair.

In July 1867, the Straits Settlements Legislative Council approved a budget of $100,000 to build a structure that was much smaller in scale than the present building we now know as the Istana. In the same month, the governor’s wife Lady Ord laid the foundation stone.

A plan for a larger building was subsequently approved, but the money set aside was insufficient. McNair managed to get the additional funds he needed by pointing out unanticipated construction challenges, such as the need to build a granite foundation. An upcoming visit by Prince Albert – Duke of Edinburgh and the second son of Queen Victoria – in December 1869 hastened the pace of construction.6

Government House took shape under the hands of convict labourers from India, Ceylon and Hong Kong who were paid 20 cents a day to work as stone masons, plumbers, carpenters, painters and stone cutters. It was completed in October 1869 at a cost of $185,000.7

The stately building was designed in the neo-Palladian style8 and reflected architectural elements of the East and West: imposing Greek-style columns, cornices and arches reminiscent of buildings in Europe, and wide verandahs, large louvred windows and dwarfed piers adapted from traditional Malay architecture.

Between 1869 and 1959, Government House was home to 18 colonial governors.9 Government House also bore witness to a procession of kings, sultans, dukes and other members of the nobility, who graced the halls with their presence. These included the Sultan of Selangor Abdul Samad, who called on the governor in 1890 with an entourage of over 30 people, and King Chulalongkorn of Siam who visited with a reported 66 people in 1871.10

Given Singapore’s prime geographical location, the island was a popular stopover for European visitors en route to China, and some of these visitors put up at Government House on transit. These included the likes of the English botanical artist Marianne North, who visited in 1876 and waxed lyrical about the lush vegetation around Government House; Annie Brassey,11 inveterate traveller and wife of the first Earl of Brassey, who stayed over in 1877 when her schooner had to be replenished with coal at the Tanjong Pagar docks; and Prince Albert Victor and his brother, Prince George of Wales, who were treated to a royal party at the house by Governor Frederick Weld in 1882.12

On occasion, the large and leafy expanse of grounds hosted garden parties, while dances were held in the capacious ballrooms. Retired colonel John Morrice, who lived in the servants’ quarters of Government House between 1935 and 1947 as his father worked as a waiter there, recalled:

“During the time of the British there used to be a lot of parties and tea dances, once a fortnight or month. We all used to hang around there and watch from the side. The ladies wore long dresses all the time…”13

The War Years

Those halcyon days ended as the Japanese advanced down Malaya in late 1941. In February 1942, a cellar at Government House, which was connected to a tunnel leading out to an opening beyond its domain, was bombed by the Japanese. When the soldiers discovered the escape hatch, they sealed it by pushing grenades into the tunnel, killing a number of staff and partially damaging the cellar.14

The remaining staff escaped and hid in houses along Kampong Java Road. When Count Hisaichi Terauchi, a Field Marshall in the Imperial Japanese Army and Commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, took up residence in Government House in March 1943, he brought them back. Donning their old uniforms, the staff served their new boss and had to learn Japanese.15

Thankfully, Terauchi left much of the building intact, apart from redecorating some rooms to give it a Japanese flavour, including introducing some Japanese-style screens and getting rid of items with the British Royal crest on them, such as the crockery. However, he largely respected and preserved what was contained in the building.

Abdul Gaffor bin Abdul Hamid, whose father worked as a butler in Government House, was born on the grounds in 1931 and spent his childhood and teen years there. He recalled:

“Before the Japanese came in, we were still here [in the Istana]. We had a shelter underneath the building… air raid shelter for all the staff. When there was heavy bombardment, the governor said don’t stay here because [it] was dangerous. Then they got us a lorry… We moved to some old house at Java Road.

“When the Japanese came, we all came back. They asked us to come back. My father did the cleaning and gardening… A year before they went off, they called me to come and work in the Istana because I was learning Japanese. I said okay because they gave us oil and fish… I attended a Japanese school for 2 ½ years. I learnt Japanese – katakana, hiragana – and Malay. Whenever visitors wanted to come into the Istana, the Japanese sentry would call me to translate. The Japanese were quite polite to us.”16

When the Japanese surrendered in September 1945, the British returned and reoccupied Government House once again.

From Government House to Istana

The biggest transformation to the building took place after 1959, when Singapore embarked on its road to independence and the Istana became a symbol of an increasingly independent Singapore and not of colonial Britain.

When Singapore achieved internal self-government in 1959, Government House was renamed Istana Negara Singapura, or Palace of the State of Singapore. This was shortened to The Istana when Singapore separated from the Federation of Malaysia on 9 August 1965 to become an independent, sovereign nation.

From housing colonial governors who hailed from Britain, the Istana became the designated official residence for the presidents of Singapore. The last governor of Singapore was William Allmond Codrington Goode, who served as the Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Malay for “Head of State”) from June to December 1959, before making way for Yusof Ishak, the first local-born Head of State. When Singapore gained independence, Yusof was sworn in as the country’s first president.

While the Istana still remains the official residence of Singapore’s presidents, only two have actually lived on the Istana grounds and, even then, not in the main building: Yusof lived in an outlying bungalow named Sri Melati, which was built in 1869 to house the colonial under-secretaries.17 Third president Devan Nair lived in the Lodge, which was built to replace Sri Melati after it was torn down in the 1970s when termite infestation rendered it structurally unsafe.

Yusof explained at the time when he became Head of State that he felt that the Istana’s main building was too lavish for him and his three children. The family stayed in Sri Melati for 11 years, between 1959 and 1970, where Yusof indulged in his passion for gardening by growing papayas and orchids.18 Devan Nair and his family lived in the Lodge between 1981 and 1985.19 The other presidents, on the other hand, felt more comfortable living in their own homes elsewhere in Singapore.

Aside from its occupants, the way of life in the Istana also changed when local staff ran the Istana after the British left. In 1960, the first Asian Comptroller of Household Jean Leembruggen, a Eurasian from Melaka, was appointed. Her husband, Geoffrey Leembruggen, was then acting permanent secretary at the Ministry of Health.

Yusof’s wife, First Lady Puan Noor Aishah, personally supervised the menu and food preparation in the Istana, from English-style fare like roast beef and Yorkshire pudding to local favourites.20 The skilled home chef introduced dishes like nasi sambal, chicken rendang and chap chye which were served to foreign nitaries. She was particularly well known for her gula melaka dessert made with sago, egg white and coconut milk.21 The First Lady was also known for her shrimp and sardine sambal sandwich rolls:

“I wanted something different so instead of cutting the sandwiches into triangles or rectangles like usual sandwiches, I would roll them up and cut them into circular segments like a Swiss Roll. That way, the ‘sandwiches’ would be easier to eat… we usually had two fillings – sardines and shrimp sambal.”22

Puan Noor Aishah also trained the Istana’s chefs to whip up her signature dishes which included curry puffs and kueh onde onde.23 One of her trainees, Wong Shang Hoon, is still said to be cooking up a storm in the Istana today.

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the new nation began establishing diplomatic ties with other countries, and soon, visitors from foreign countries started streaming in. Memorable visits include those by West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, China’s Deng Xiaoping and Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Queen Elizabeth visited Singapore in 1972, 1989 and 2006 and each of her visits caused much excitement among the Istana’s household staff. Senior Butler Ismail Abdul Ghani recalled meeting her in 1972 and 2006.24

“The first time I met Queen Elizabeth, I was one of two Istana butlers who was assigned to attend to her personal needs. I didn’t think she would remember me. But when I next saw her, at an event where all the butlers lined up in a row to greet her, she stopped when she came to me and said – ‘I remember you’. I felt so happy!”25

Sometimes, visitors were invited to stay at the Istana. The guest facilities, which no longer exist today, comprised two rows of five rooms on the second floor of the main building. Guests were supplied with Lux brand soap, one box of detergent in the form of soap flakes as well as toothbrushes and toothpaste.26 VIPs who had spent the night at the Istana include Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, who stayed with his two pet dogs in 1968,27 and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in 1978.

Yusof and his wife also opened up the Istana to ordinary Singaporeans. Puan Noor Aishah was the Patron of Girl Guides Singapore, and she would invite the Guides to hold their annual campfire on the Istana grounds once a year.28 Puan Noor Aishah’s life changed dramatically after she became First Lady:

“Life used to be simple. But once we moved into the Istana, we became very busy; there were many changes in our lives and there was a lot of protocol to observe. I remember there would be courtesy calls in the morning, tea parties in the afternoon, and I had to meet many charity organisations which were coming to me for help. All the meetings and social gatherings were necessary as we were new and we had to get to know people to win their confidence.”29

It was Yusof who started the Istana’s open house tradition. The very first open house event took place on 1 January 1960, between 8 am and 6 pm, on New Year’s Day. Numerous slides, swings and seesaws were trotted out for children, while the police band entertained the public.30

The First Major Renovations

By the time Singapore’s fifth president Ong Teng Cheong took over, the Istana had stood for over 120 years and was in need of a major overhaul.

Renovation works were carried out between 1996 and 1998. This was the Istana’s first major infrastructural upgrade, and the aim was to create more room for state functions and to replace the building’s ageing mechanical and electrical services while preserving its heritage features. Ong, who served as president from 1993 to 1999, explained the need for the makeover:

“[The Istana] is a stately building, very grand, very symmetrical, as it should be for an institutional building. But internally, it needs refurbishing. Where we can, we will try to renovate the place and try to bring back its old grace.”31

Many new features were added, including centralised air-conditioning, mechanically activated louvres, restored timber rafters and beams, automatic sliding doors and a dedicated Ceremonial Plaza with four flagpoles for military displays. Previously, these displays were performed at the airport when foreign guests disembarked from the aeroplane.32

The Istana gardens were also overhauled and professionally landscaped, a Herculean effort that took the team two years and which involved making trips to countries such as Australia to source for unusual plants.

The front lawn of the main garden was originally designed as a traditional European garden.33 To frame the Istana’s main building upon approach, the team transplanted 18 majestic meninjau trees, each soaring over 10 metres in height, from other parts of Singapore to the periphery of the circular front lawn.

The Istana Today

The main building of the Istana exudes elegance, while retaining its heritage and historical roots.

State gifts bestowed by foreign visitors are showcased in the main building as well as at the Istana Heritage Gallery, which is located at the Istana Park opposite the Istana’s main entrance facing Orchard Road. The walls of the main building are also decorated with artworks by local artists, some commissioned by former presidents.

Foreign VIPs continue to pass through the halls of the Istana, among them US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, who were in Singapore for the historic Trump-Kim Summit on 12 June 2018. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong hosted Kim at the Istana on 10 June, while Trump and his delegation attended a working lunch there on 11 June.34

For many Singaporeans, the Istana is a place associated with the highest honours in the land. All manner of ceremonies honouring individuals at the top of their professions are held there, such as the President’s Award for Teachers, the President’s Award for Nurses and the Cultural Medallion.

A total of eight presidents have passed through the halls of the Istana. The current president is Madam Halimah Yacob, Singapore’s first female president.

Madam Halimah declared at the beginning of her term in 2017 that she wanted to make the Istana grounds more accessible to the people, including the elderly and those with special needs. She launched the Picnic@Istana series when she took office, where four picnics would be held each year for underprivileged children as well as those with special needs.35 Another programme that she initiated, Garden Tours@Istana, has welcomed senior citizens, hospice patients and their caregivers, and patients from the Institute of Mental Health.36

On 6 October 2019, the Istana held its very first open house event at night, hosted by Madam Halimah and her husband Mohamed Abdullah Alhabshee, to mark its 150th anniversary. Highlights included a lightshow on the walls of the main building depicting the Istana’s heritage and history over the years, and performances by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra and other local talents.37

Soon after, the Istana launched an interactive multimedia website with augmented reality features titled “Inside the Istana” in collaboration with The Straits Times. The website allows people to “walk around” the Istana and experience the sights and sounds on their computers or smartphones.38

While the Istana may have started out as symbol of imperial strength and power 150 years ago, today it is a national icon and occupies a special place close to the hearts of Singaporeans.

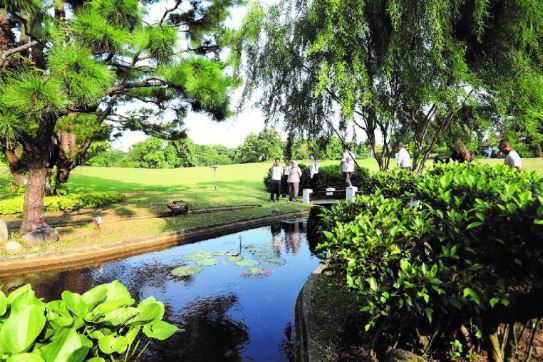

JEWELLED GREENS OF THE ISTANA

Landscaping has always been an essential element of the Istana’s grounds. From the beginning, a nursery was established and many varieties of fruit and flowering trees and shrubs were planted on the 41 hectares that Government House stood on.39

In the years following Singapore’s independence, the gardens grew in tandem with founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s efforts to turn Singapore into a garden city. Remembered by many as Singapore’s chief gardener, Lee used the Istana as a testbed for flora to be planted in the rest of Singapore. He also felt it was important for the Istana’s gardens to make an impression on visitors. He said:

“When they drove into the Istana domain, they would see right in the heart of the city a green oasis, 90 acres of immaculate rolling lawns and woodland, and nestling between them a nine-hole golf course. Without a word being said, they would know that Singaporeans were competent, disciplined and reliable, a people who would learn the skills they required soon enough.”40

When Lee came across the foxtail palm – the name inspired by the bushy fronds resembling the tail of a fox – while on a visit to Australia, he asked for it to be planted on the Istana grounds. Visitors to the Istana today can still see this palm, which is found beside the iconic Swan Pond.41

The Swan Pond, home to a pair of white mute swans, is also a legacy of Lee’s. It was constructed in 1968 at his request and is the largest of various ponds on the Istana grounds.42

As Lee often spent long days working inside the Istana building, the gardens were a welcome respite. He and Mrs Lee would visit and feed the swans during their evening walks and he would sometimes pick a cluster of white flowers, commonly known as the breadflower, for his wife. These flowers, with their sweet pandan fragrance, were a favourite of Mrs Lee’s.43

The fruit trees on the grounds also provided an occasional treat for the Istana staff who used to reside in the staff quarters on the grounds. Many of them, and their children, recall plucking fruit off the trees.

Today, more than 10,000 trees and palms – making up some 260 species – grow on the grounds of the Istana. Around 100 are mature trees with girths of over 4 metres. The oldest tree is a Tembusu, which is believed to have been planted in 1867, two years before the Istana was completed. This tree is located next to Sri Temasek,44 which is the designated official residence of the prime minister of Singapore.

The gardens have naturally become home for a great variety of wildlife, including butterflies like the Lesser Grass Blue Butterfly, which is only one centimeter in size, dragonflies, fish, terrapins, squirrels, bats, flying foxes, monitor lizards, snakes and weaver ants, which are found on trees like the Tembusu.45

As a gazetted bird sanctuary, the Istana grounds teem with avian life. A survey carried out in April 2019 registered 89 bird species.46 In fact, current Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has had a barn owl visit him in his Sri Temasek office in 2013 and 2015. In both cases, the Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority of Singapore and the Jurong Bird Park had to be called in to trap the bird and release it behind Sri Temasek. He saw the bird again in 2017, but this time it was perched in the overhang along the exterior of the Istana.47

As for larger animals, horses used to be stabled in the Istana, though no longer today. In the 1950s, an elephant was briefly a resident of the Istana’s grounds and it aided the gardeners by supplying bounteous composting material. However, the elephant was apparently sent to Malaya in early 1960.48

Wong Sher Maine is a freelance writer who has written two books about the Istana: Our Istana was published in 2015, while 50 Best Kept Secrets of the Istana: People and Places was published in 2019.

Wong Sher Maine is a freelance writer who has written two books about the Istana: Our Istana was published in 2015, while 50 Best Kept Secrets of the Istana: People and Places was published in 2019.

Notes

-

New Government House. (1869, April 24). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Settlements, comprising Singapore, Melaka and Penang, was formed in 1826. It was initially an administrative unit of the British East India Company (1826–67) before it came under direct control of the Colonial Office in London as a crown colony (1867–1946). Following the dissolution of the Straits Settlements in 1946, Singapore was made a crown colony, while Melaka and Penang became part of the Malayan Union. ↩

-

The First Resident and Commandant of Singapore was William Farquhar (1819–23), who was succeeded by John Crawfurd as Resident (1823–26). Between 1826 and 1867, Singapore was governed by Resident Councillors. When Singapore became part of the Straits Settlements along with Melaka and Penang in 1867, the first governor was Robert Fullerton (1826–30). Singapore’s last governor was William Goode (1957–59). See National Library Board. (2017). Past and present leaders of Singapore written by Vernon Cornelius. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Government Hill was initially called Bukit Larangan (“Forbidden Hill” in Malay), When Stamford Raffles built a wooden house with a thatched roof for himself on the hill in 1822, it became known as Government Hill. The house was later used as the residence of the colonial governors of Singapore. When the house was demolished to make way for Fort Canning in 1859, Government Hill was renamed Fort Canning Hill. ↩

-

Cheah, S. (2019). 50 best kept secrets of the Istana: Flora and fauna (p. 9). Singapore: Published by Epigram for the Istana, the office of the President of the Republic of Singapore. (Call no.:RSING 959.57 CHE-[HIS) ↩

-

Seet, K.K, & Myddelton, D.R. (2000). The Istana (p. 30). Singapore: Times Editions (Call no.: RSING q725.17095957 IST) ↩

-

President’s Office. (2018). The Istana: History. Retrieved from President of the Republic of Singapore website. ↩

-

Palladianism or Palladian architecture is a European style of architecture influenced by the 16th-century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–80). The style is characterised by classical forms, symmetry and strict proportions. Neo-Palladian is English Palladian architecture popular in the 18th century. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2010). The Istana written by Vernon Cornelius. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Hoe, I. (2019). 50 best kept secrets of the Istana: History and heritage (p. 37). Singapore: Published by Epigram for the Istana, the office of the President of the Republic of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 HOE-[HIS]) ↩

-

See Tan, B. (2018, Jul–Sep). Globetrotting mums: Then and now. BiblioAsia, 14 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Seet & Myddelton, 2000, pp. 43, 45. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2008, April 21). Oral history interview with Morrice, John (Colonel) (Retired) [Transcript of recording no. 003306/13/1, p. 4]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Seet & Myddelton, 2000, p. 68; Tan, W.K., et al. (2003). Gardens of the Istana (p. 50). Singapore: National Parks Board. (Call no.: RSING q635.095957 GAR) ↩

-

Chou, C. (Interviewer). (1994, May 30). Oral history interview with Mr Abdul Gaffor bin Abdul Hamid [Transcript of recording no. 001430/2/1, pp. 3–5.] Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Seet & Myddelton, 2000, p. 68. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Mr Abdul Gaffor bin Abdul Hamid, 30 May 1994, pp. 3–5. ↩

-

Leong, C. (2011). The Istana (p. 129). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 725.17095957 LEO); Tan, K.Y.L. (2017). Puan Noor Aishah: Singapore’s first lady (p. 68). Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 TAN) ↩

-

Our Istana through the years (p. 30). (2015). Singapore: Office of the President of the Republic of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 OUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

Wong, S.M. (2019). 50 best kept secrets of the Istana: People and places (p. 22). Singapore: Published by Epigram for the Istana, the office of the President of the Republic of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 WON-[HIS]) ↩

-

Our Istana through the years, 2015, p. 27. ↩

-

Zulaiqah Abdul Rahim. (2019, July 15). Bangga ikut jejak arwah datuk dan ayah jadi ‘butler’ di Istana. Berita Harian, p. 1. ↩

-

Our Istana through the years, 2015, p. 43. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (2007, August 11). Oral history interview with Lee Ah Jee [Transcript of recording no. 003215/2/1, pp. 23, 29–31]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Seet & Myddelton, 2000, p. 96. ↩

-

Our Istana through the years, 2015, p. 170. ↩

-

Our Istana through the years, 2015, p. 28. ↩

-

Nur Asyiqin Mohamad Salleh. (2018, June 10). North Korean leader Kim Jong Un meets Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong ahead of Trump-Kim summit. The Straits Times; Tan, D.W. (2018, June 11). Trump thanks PM Lee for Singapore’s hospitality, thinks Trump-Kim summit will ‘work out nicely’. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

New picnic series lets more people enjoy the Istana grounds. (2017, November 17). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Tour of Istana garden for patients, caregivers. (2018, September 11). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Ang, P. (2019, September 12). Tickets to first public Istana event at night to mark 150 years available from Sept 13. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Zhuo, T. (2019, October 28). Step into Istana without stepping out of your house. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Leong, C. (2011). The Istana (p. 96). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 725.17095957 LEO) ↩

-

Ng, H. (2016, March 20). President plants tembusu tree in Istana and pays tribute to Mr Lee. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 Mar 2016, p. 6. ↩

-

Sri Temasek, designed by Colonial Engineer Major John Frederick Adolphus McNair, is a two-storey bungalow built on the grounds of the Istana in 1869. During the colonial era, it was the residence of the colonial secretary or chief secretary. When Singapore attained self-government in 1959, Sri Temasek became the official residence of the prime minister of Singapore. However, none of the prime ministers have ever lived there. ↩

-

Tan, W.K., et al. (2003). Gardens of the Istana (p. 170). Singapore: National Parks Board. (Call no.: RSING q635.095957 GAR) ↩

-

Cheah, 2019, p. 69; The Istana (p. 97). (2019). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 725.17095957 IST) ↩

-

Tan, A. (2013, November 21). Barn owl a surprise visitor at PM Lee Hsien Loong’s office. The Straits Times; Lam, L. (2017, August 26). Barn owl visits Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong again, for the third time in five years. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩