Early Printing In Indochina

In the first of two essays on the history of printing in mainland Southeast Asia, Gracie Lee examines the impact of the printing press in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

Printing in Southeast Asia was largely established on the back of European colonialism and expansion in the region. Motivated by the need to disseminate official government information and Christian knowledge, colonial governments and missionary societies set up the earliest printing presses in Southeast Asia and introduced Western printing methods such as letterpress aprinting1 and lithography2.

Prior to this, writing in Mainland Southeast Asia largely consisted of inscriptions on stone or bamboo, or handwritten manuscripts composed of palm leaf, bark or paper. These early books were mainly in the form of palm-leaf manuscripts and folding books.3

As the production and function of books at the time were deeply rooted in the traditions of religion and the aristocracy, common topics discussed in these books included subjects such as religion, history, law, royal genealogies, classical literature, magic, healing and divination. The adoption of Western-style printing technology, however, transformed the way in which texts were produced and consumed in Southeast Asia, much as it did in Europe earlier.4

Vietnam

While most countries in mainland Southeast Asia were introduced to printing technology in the 19th century, Vietnam is an exception. There, the Chinese technique of woodblock printing was thought to have been in use as early as the 13th century. Vietnamese annals suggest that a version of the Chinese Buddhist canon was printed in Vietnam between 1295 and 1299.5

The spread of printing in the country is commonly attributed to the 15th-century Vietnamese scholar Luong Nhu Hoc, who imparted the craft to the villages of Hong Lac and Lieu Trang in Hai Hung province. As a result, these villages later prospered as centres of printing. Some of these artisans, who specialised in woodblock engraving and paper-making, later relocated and set up publishing houses in the capital Thang Long (present-day Hanoi), which grew as an urban centre for book publishing and retail. In 1820, the Nguyen dynasty (1802–1945) – the last royal house of imperial Vietnam – sought to consolidate all printing in its new capital Hue.6

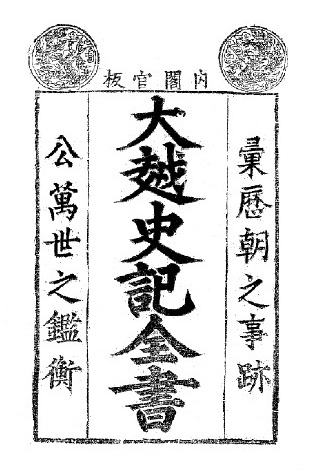

The oldest printed book in Vietnam is widely regarded to be the Chinh Hoa edition (named after the Chinh Hoa reign era which lasted from 1680 to 1705) of Dai Viet su ky toan thu (Complete Book of the History of Great Viet; 1697). This monumental work was compiled by the royal historian Ngo Si Lien of the Le dynasty (1428–1789) in the 15th century, and updated by successive historians.7

Scholars generally concur that locally produced books were accessible in Vietnam by the 15th century, at least among the intellectual elite, a class created by the country’s institutionalised system of court examinations modelled on the Chinese bureaucracy. These texts existed alongside manuscripts and books imported from China. Up until the early 20th century, woodblock printing was the main technique used in Vietnam, and texts were written in either classical Chinese or chu nom – Chinese characters that had been adapted for the Vietnamese language.8

The period of French colonisation dramatically altered the traditional print culture of Vietnam: it introduced Western typographic processes and increased the popularity of quoc ngu, a Romanised writing system for Vietnamese. The government presses established by the French administration in Cochinchina (South Vietnam) in 1862 and Tonkin (North Vietnam) in 1883 were among the earliest printing presses in Vietnam.

By the late 19th century, several commercial French publishing establishments had taken root in French Indochina. In the 1870s, the Catholic mission set up a publishing house known as the Imprimerie de la Mission on the premises of Tan Dinh Church in Saigon. The printing press produced early publications such as Huan mong khuc ca (1884), an Annamese primer, and French-Vietnamese dictionary Petit dictionnaire Francais-Annamite (1884).

In the 1880s, Francois-Henri Schneider, a former foreman with the Imprimerie du Protectorat in Hanoi, branched out to set up his own publishing firm, F.H. Schneider. This would later become one of the largest publishers in Vietnam, with offices in Hanoi, Haiphong and Saigon. Among other things, it published Bulletin de l’Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient (1901–), a leading scholarly journal on the archaeology, philology, geography, history and religion of Indochina that is still in print today. In 1907, the firm’s Hanoi-Haiphong office was renamed Imprimerie d’Extreme-Orient (IDEO). To compete against French publishing companies in Saigon, Dinh Thai Son started one of the earliest Vietnamese publishing houses, the Imprimerie de l’Union9

Local book publishing flourished with the widespread use of quoc ngu, or Romanised Vietnamese, which had been devised by Portuguese missionaries in the 17th century and designated the official writing system by the French administration in 1910. The ease of learning quoc ngu aided the proliferation of printing and education in Vietnam.10

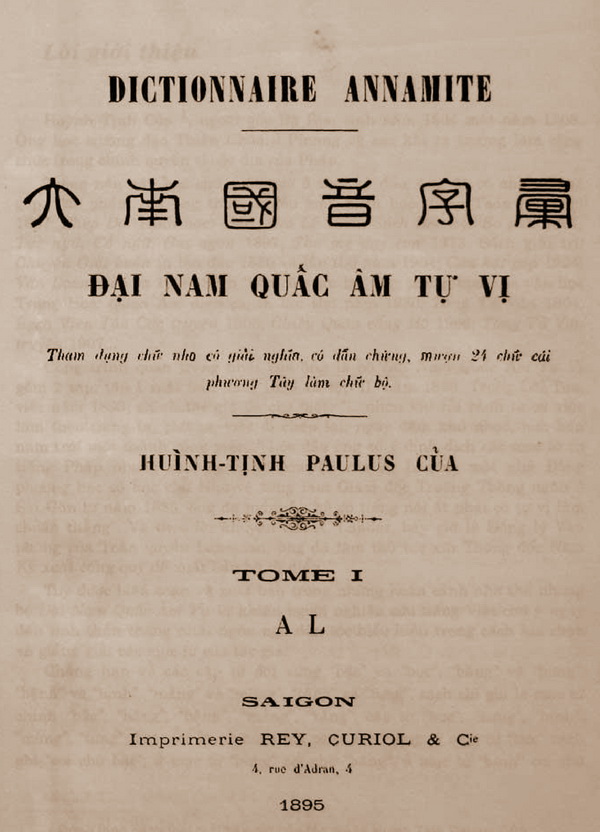

In 1865, the first newspaper in Romanised Vietnamese, Gia Dịnh Bao (News of Gia Dinh), was published and, in 1895, the first Vietnamese-authored dictionary by scholar Paulus Cua (Vietnamese name Huynh Tinh Cua), Dai Nam Quac Am Tu Vi (The Dictionary of National Language), was produced. By 1920, modern print technology had replaced woodblock printing as the main printing technique in Vietnam.

Cambodia

Compared to Vietnam, printing in Cambodia developed much later. Scholars have attributed this to factors such as the small literate class, the challenges of creating printing types in the Khmer language, and resistance from traditionalist monks who saw the copying of religious texts as a sacred performative act that was integral to the practice of merit-making.11

Printing was introduced to Cambodia during the period of the French Protectorate (1863–1953). Until the 1880s, many of the earliest publications about Cambodia were published outside the kingdom, in particular Vietnam, and were in French. Examples include the Bulletin officiel de l’Expedition de Cochinchine (1862) and the Bulletin officiel du Cambodge (1884). The latter is the first official organ and administrative bulletin of colonial Cambodia.

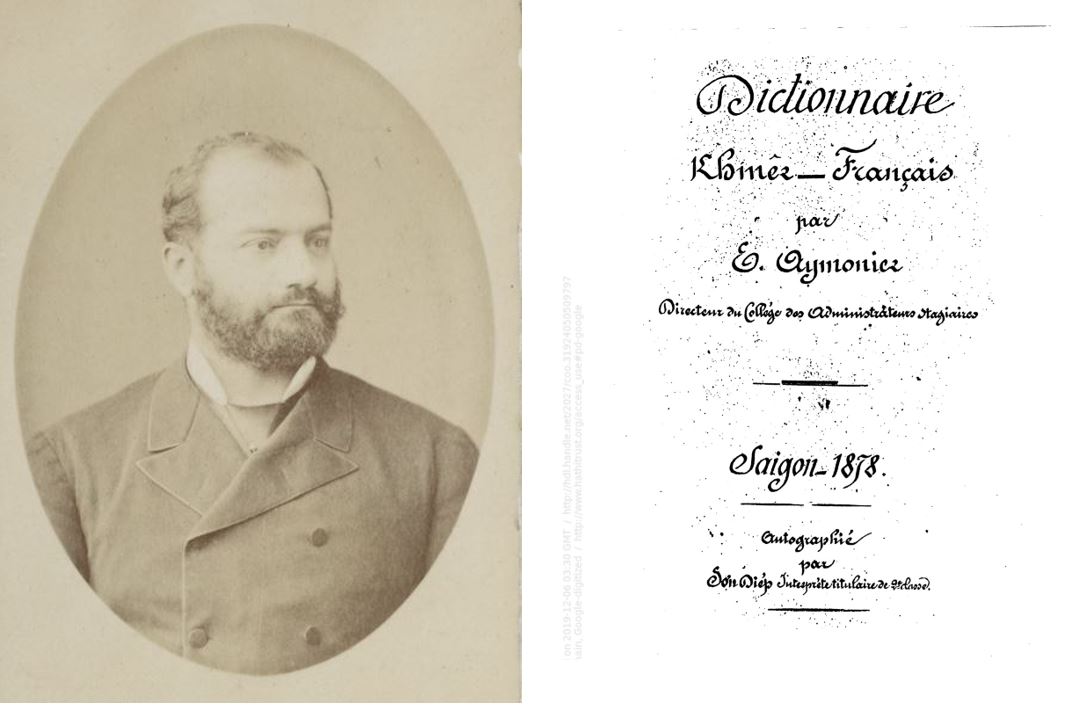

Privately published works such as French linguist Etienne Aymonier’s collection of popular Khmer folklores were also produced in Vietnam. Lithographed in Saigon in 1878, this bilingual work – in Khmer and French – is regarded as the first collection of Cambodian oral tales ever recorded on paper in the vernacular. Additionally, Aymonier compiled the first Khmer-French dictionary, Dictionnaire Khmer-Francais (1878), in Saigon with assistance from local interpreter Son Diep.12

(Right) The first Khmer-French dictionary, Dictionnaire Khmer-Francais ( 1878), was published in Saigon using lithography. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from HathiTrust website.

It was not until around 1886 that the first official printing press in Cambodia, the Imprimerie du Protectorat, was established by the French in Phnom Penh. One of its earliest publications was the first printed periodical in Cambodia titled Annuaire Illustre du Cambodge (1890).

In the early 20th century, a royal printing office was set up in the palace in Phnom Penh to publish sutras (Buddhist scriptures), laws and regulations. Its maiden publication was likely the programme sheet produced in French for the inauguration of the Preah Keo pagoda, titled Programme des fetes donnees a l’occasion de l’inauguration de la Pagode de Prah Keo en 1903 (1903). In 1911, the first official gazette in the Khmer script, Reachekech (Royal Gazette), commenced publication. It remains in circulation today, although primarily as an online publication.13

The European concept of the printed book as a tool for the dissemination of information marked a paradigm shift from the traditional textual practices of Cambodia. As this view gained wider acceptance in Cambodian society from the early 20th century onwards, a number of French and Cambodian printing houses began opening in Phnom Penh, and published secular works such as newspapers and local literature.

The need to educate also spurred the publishing of textbooks in the vernacular. Cambodia’s first newspaper, Le Petit Cambodgien, made its appearance around 1899. The biweekly newspaper was published privately and produced using lithography. The first Cambodian newspaper printed by typography was La Gazette Khmer (1918–1919).14

No overview on the history of printing in Cambodia would be complete without mentioning the history of printing in the Khmer script. Most sources cite the first Khmer type fonts as being cast at the Imprimerie Nationale, the official printing office of the French government, in Paris in 1877. However, type designer Zachary Scheuren has pointed out that, as early as the 1840s, Austrian printer Alois Auer’s Sprachenhalle, a magnum opus containing more than 600 language samples, had already included a Khmer font type called “Kambog’a”.15

The person most associated with the pioneering development of Khmer font types is Marie-Joseph Guesdon. Guesdon was a French Jesuit priest who arrived in Cambodia in 1874, where he cultivated an abiding interest in the country and its language. On his return to Paris, Guesdon cast his own Khmer types in 1894, and collaborated with French publishing house Plon-Nourrit to release books in Khmer. More importantly, Guesdon was very likely the unnamed French missionary who participated in the design of Parisian foundry Deberny & Cie’s Khmer font types. These types were later supplied to major printers of Cambodian works, such as the Imprimerie du Protectorat, Plon-Nourrit and F.H. Schneider, and used in a wide array of publications from the turn of the 20th century.16

Laos

Of the three states in French Indochina, Laos was the last to adopt modern printing technology, with the first Lao publications reportedly produced only in the early 20th century. During the period of French colonisation (1893–1953), official publications on Laos were mostly published in Vietnam or France. Thailand was also a source of Lao printed works.

During the 1930s, monks in the capital Vientiane were said to have procured printed traditional Lao stories from northeastern Thailand and re-copied them onto palm leaves for circulation. Due to its late introduction, the high cost of printing and the small readership base, book production remained low in Laos in the early 20th century.17

Some of the earliest Lao publications were language guides. The Imprimerie de la Société des Missions-Etrangères, a Catholic press in Hong Kong, released Lexique Francais-Laocien in 1904 and Dictionnaire Laotien-Francais in 1912.

In 1935, the first Lao grammar book was published under the auspices of the Institut Bouddhique (Buddhist Institute) established in Vientiane by the French in 1931. The four-volume work, based on the study of Buddhist texts in the Lao language, was compiled by Maha Sila Viravong, regarded as one of the greatest modern scholars of Laotian history and literature.18 Sila Viravong also wrote Phongsawadan Lao (A Lao History), which was used as a school textbook for many years. Published by the Lao Ministry of Education in 1957, the text remains a standard reference on Lao history today.19

The French colonial government press, the Imprimerie du Gouvernement du Laos, was established in Vientiane by the 1910s. Among its earliest publications was Essai de Cours de Langue Laotienne (1917), a Lao language textbook written for French speakers by Pierre Le Ky Huong. Le was the Vietnamese director of the Lao government printing office and translator for the Resident-Superieur (the chief colonial official who answered to the Governor-General of Indochina). An early proponent of the standardisation of written Lao, Le also initiated the publication of Chot Mai Het Lao, the Lao edition of the Bulletin Officiel Laotien, a government communique in French.20 However, its exact year of publication cannot be ascertained.

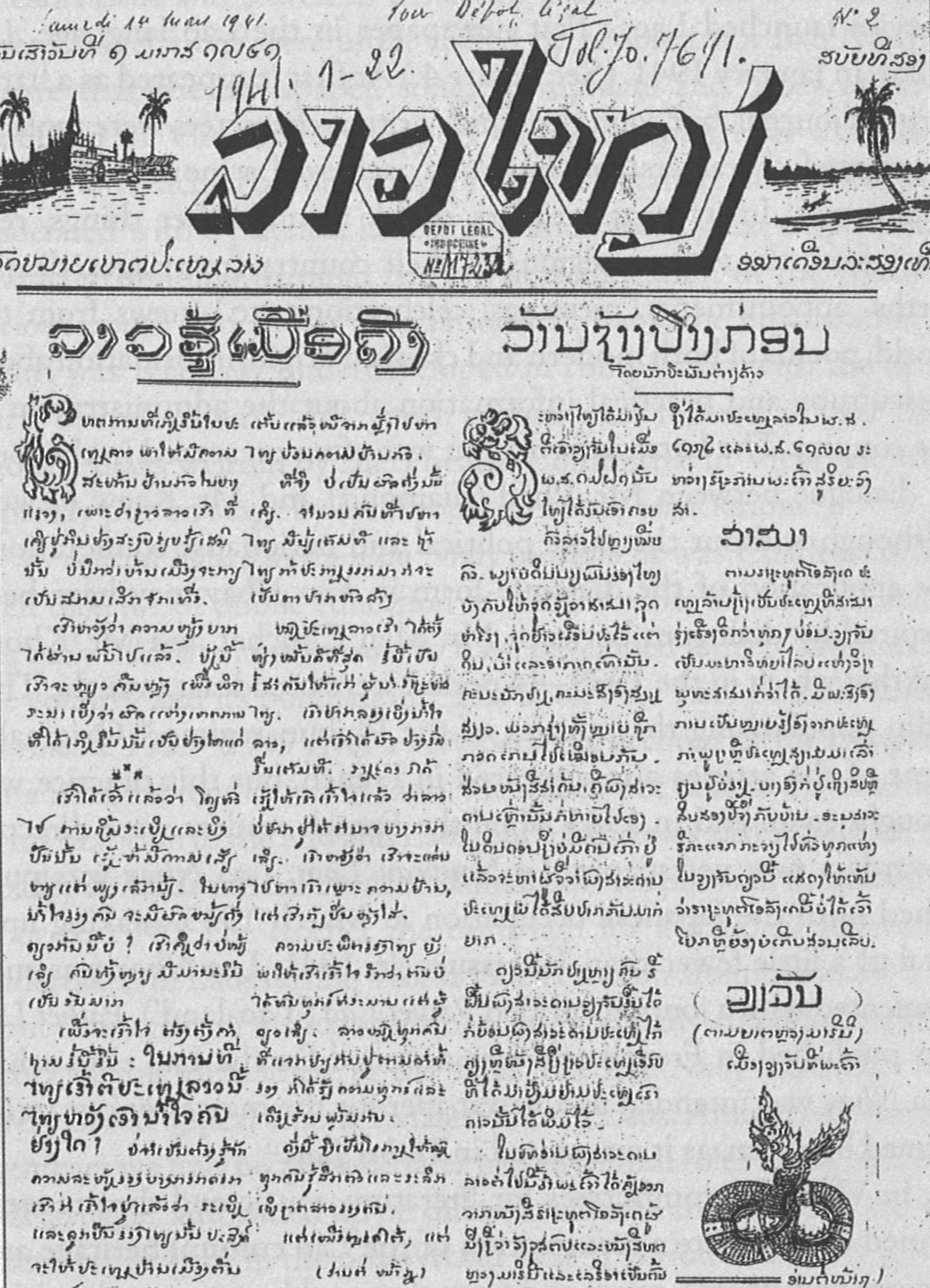

The first Lao-language newspaper, Lao Nhay, which means “Great Laos”, was published only in 1941 as part of a Vichy French-sponsored nationalist movement. The fortnightly periodical featured political news, articles on local life as well as literary works. The newspaper also issued a French supplement, Pathet Lao (Lao-land), for the French-educated Lao elite. In 1945, during the Japanese Occupation, Lao Nhay was supplanted by Lao Chaleun (Prosperous Lao), a Japanese-sponsored newspaper.21

The publisher of Lao Nhay also published other Lao works, such as the national anthem of Laos and the first modern Lao novel, Phraphuttharup Saksit (The Sacred Buddha Image; 1944). Written by Pierre Somchine Nginn under the pen name Lao Chindamani, the story follows a detective of French and Lao descent as he investigates the disappearance of a Buddha statue from the Wat Si Saket temple in Vientiane. The book has an introduction in French as well as a French title, La Statuette Merveilleuse: Nouvelle Laotienne.22

French colonisation and the emergence of commercial publishers who used Western printing technology were key factors in the disruption of traditional methods of book production and consumption in Indochina. Their appearance saw greater diversity in the books produced, ranging from language guides and newspapers to modern novels – thereby overtaking traditional publications such as religious texts.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Notes

-

Letterpress printing or typographic printing is the process in which copies of an image are produced by making an impression of an inked raised surface onto paper. The ink-bearing surface is composed, character by character, by a typesetter, These characters are the movable components of type that is designed and manufactured by type foundries. ↩

-

Lithography is a printing process that works on the principle that water and oil do not mix. The printer first writes or draws on a semi-porous flat surface of a printing stone (usually limestone) using a greasy substance such as a crayon. The surface is moistened and a layer of oil-based ink would then be applied to the surface with a roller. The ink will adhere to the greasy marks but will be repelled by the water. The ink on the stone is then transferred onto a sheet of paper. ↩

-

Books made of paper folded in a concertina format. ↩

-

Suarez, M.F., & Woudhuysen, H.R. (Eds.). (2013). The book: A global history (pp. 107–115, 622–634). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: 002.09 BOO) ↩

-

Kornicki, P.F. (2018). Languages, scripts, and Chinese texts in East Asia (p. 117). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Herbert, P., & Milner, A. (Eds.). (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and literature: A select guide (p. 82). Arran, Scotland: Kiscadale Publications. (Call no.: RSING 495 SOU); Nguyen, Q., & Phan, C.T. (1991). My thuat o lang = Art in the Vietnamese village (pp. 174–175). Hanoi: My Thuat Ha Noi. (Call no.: RSEA 700.9597 NGU); Nguyen, T.H., & Cohen, B. (2002). Economic history of Hanoi in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries (pp. 122–125, 179–185, 209). Hanoi: National political publishing house. (Call no.: RSEA 959.7 NGU); McHale, S. (2007). Vietnamese print culture under French colonial rule: The emergence of a public sphere (pp. 380–381). In L. Chia & W.L. Idema. (Eds.). Books in numbers: Seventy-fifth anniversary of the Harvard-Yenching Library: Conference papers. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. (Call no.: R 002.095 BOO) ↩

-

Kornicki, P. (2009). Japan, Korea and Vietnam (pp. 122–124). In S. Eliot & J. Rose. (Eds.). A companion to the history of the book. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. (Call no.: R 002.09 COM); Li, T. (2001). The imported book trade and Confucian learning in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Vietnam (p. 169). In M. Aung-Thwin, M & K.R. Hall. (Eds.) New perspectives on the history and historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing explorations. London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSEA 959.0072 NEW); Nguyen & Phan, 1991, pp. 174–175; Taylor, K.W. (2013). A history of the Vietnamese (p. 628). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959.7 TAY) ↩

-

Kornicki, 2009, p. 122; Li, 2001, pp. 169–170; McHale, S. (2007). Vietnamese print culture under French colonial rule: The emergence of a public sphere (pp. 381–382). In L. Chia & W.L. Idema. (Eds.) Books in numbers: Seventy-fifth anniversary of the Harvard-Yenching Library: Conference papers. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. (Call no.: R 002.095 BOO); McHale, S. F. (2004). Printing and power: Confucianism, communism and Buddhism in the making of modern Vietnam (pp. 12–15). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.703 MAC); Elman, B.A. (Ed.) (2014). Rethinking East Asian languages, vernaculars and literacies, 1000–1919 (p. 36). Leiden: Brill. (Not available in NLB holdings); Phan, C.T. (2014, June–July). The wooden printers that saved reading. Vietnam Heritage Magazine, 5 (4). Retrieved from Vietnam Heritage website; Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 82–84. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 82–84; Kornicki, 2009, p. 122–124, McHale, 2007, p. 382–388. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 82–84; Kornicki, 2009, p. 122–124, McHale, 2007, p. 382–388; Trương, D. (2018). A brief history of Vietnamese writing. Retrieved from Vietnamese typography website. ↩

-

Scheuren, 2010, p. 21. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 70; Jarvis, H., & Arfanis, P. (2002). Publishing Cambodia (p. 4–1). Retrieved from The Center for Khmer Studies website; Edwards, P. (2006). Cambodge: The cultivation of a nation, 1860–1945 (p. 81). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959.603 EDW); Berkeley Library. (2019, September 2). Khmer: The languages of Berkeley: An online exhibition. Retrieved from Berkeley Library website. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 53–54; Nepote & Khing, 1981, pp. 62, 76; Edwards, 2004, p. 68; Jarvis & Arfanis, 2002, p. 4–1; Dara, M., & Tyrton, S. (2017, February 2). Royal gazette to move online. Retrieved from Phnom Penh Post website. ↩

-

Nepote & Khing, 1981, pp. 62–64; Jarvis & Arfanis, 2002, p. 4-1; Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 54. ↩

-

Scheuren, Z.Q. (2010). Khmer printing types and the introduction of print in Cambodia: 1877–1977 (p. 21). Retrieved from issuu website. ↩

-

Scheuren, 2010, pp. 15–29; Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 53–54; Suarez & Woudhuysen, 2013, p. 634; Edwards, 2004, p. 68. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 70; Koret, P. (1999). Introduction to Lao literature. Retrieved from SEAsite Laos website; Koret, P. (2009). The short story and contemporary Lao literature (p. 81). In T.S Yamada. (Ed.). Modern short fiction of Southeast Asia: A literary history. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Association for Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSEA 808.83108895 MOD) ↩

-

Ivarsson, S. (2008). Creating Laos: The making of a Lao space between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945 (pp. 129–131, 133–134). Copenhagen: NIAS. (Call no.: RSEA 959.403 IVA); Keyes, C.F. (2003). The politics of language in Thailand and Laos In Brown, M. E. & Ganguly, S. (Eds.) (2003). Fighting words: Language policy and ethnic relations in Asia (p. 189). Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press. (Call no.: RSEA 306.4495 FIG); Meyers, C. (2019). Lao language policy (pp. 204–205). In A. Kirkpatrick. & A.J. Liddicoat, A.J. (Eds.). The Routledge international handbook of language education policy in Asia. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge. (Call no.: R 306.4495 ROU) ↩

-

Ivarsson, 2008, pp. 113, 124, 139; Vatthana, P. (2006). Post-war Laos: The politics of culture, history and identity (p. 81). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; Copenhagen: NIAS Press; Chiang Mai: Silkworm books. (Call no.: RSING 959.4042 VAT); Soontravanich, C. (2003). Sila Viravong’s Phongsawadan Lao: A reappraisal (pp. 111–128. In C.E. Goscha & S. Ivarsson. (Eds.). Contesting visions of the Lao past: Lao historiography at the crossroads. Copenhagen: NIAS. (Call no.: RSEA 959.40072 CON) ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 70–71; Ivarsson, 2008, pp. 145–207; Gunn, G.C. (1988). Political struggles in Laos, 1930–1954 (pp. 22, 100–102). Bangkok, Thailand: Editions Duang Kamol. (Call no.: RSEA 320.9594 GUN) ↩

-

Koret, 1999; Koret, 2009, pp. 81–82; Thong-Dy & Maha Phoumi. (1947?). Le patriote lao: hymne lao. Vientiane: Éditions de Lao Nhay. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩