When Women Were Commodities

Brothels in colonial Singapore, with its large male migrant population, did a roaring trade. Adeline Foo examines the lives of the unfortunate girls and women who were sold into prostitution.

“I went a few times because of my youthful follies, to see those girls being sold to the brothels. The auction took place in front of the go-downs at the port. The zegen [pimp] took the girls out of the hold, ordered them to change their clothes and lined them up in front of a warehouse. The brothel-owners bought them on the spot in [the] auction. Good looking girls were priced between one and two thousand yen, and ordinary girls from four to five hundred yen.”1

This account by Tomijiro Onda, a Japanese barber in Singapore, describes how the trade in young girls operated here in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ships carrying girls from Japan and China reached Singapore after three weeks to a month, while junks from Hong Kong took slightly more than a week. Once these girls landed, they were sold “as if they were cattle”. Between 1900 and 1910, the average price for a Japanese woman was 500 to 600 yen, while a Chinese girl shipped in from South China cost between $150 and $500. This was a large sum considering that the average worker earned a monthly wage of about $10 to $15 in those days.2

While much has been said about Singapore’s early economic history with its focus on canny entrepreneurs and hardworking coolies, much less has been written about the seedier side of a colonial port city where men vastly outnumbered women. In 1884, there were 60,000 Chinese men but only 6,600 Chinese women, of whom an estimated 2,000 – mainly Cantonese and Teochew – worked as prostitutes.3 It is believed that as much as 80 percent of the young Chinese girls who came to Singapore in the late 1870s were sold to brothels.

Prostitution at the turn of 20th-century Singapore, as with most other things, was the result of supply rising to meet demand. Most of the prostitutes came from patriarchal societies like China and Japan. There, sexual licence and the purchase of women was a male prerogative. Abject poverty in some regions in turn pushed these women out to find work in places like Southeast Asia.4

In addition to girls who were “imported” into Singapore from elsewhere, there were others on the island who were tricked into entering the profession. In 1940, the Nanyang Siang Pau described how one hapless victim was misled:

“‘A’’s mother met a woman whom she regarded as Second Aunt, who was sympathetic towards her daughter. Second Aunt recommended ‘A’ to get a job and offered to bring her to Kuala Lumpur. She agreed and left Singapore without telling her mother. Later, they returned to Singapore and ‘A’ became a prostitute. ‘A’ chose not to find her mother because she did not wish for her to know that she was a prostitute, it was an ugly thing. She only wished to save up enough money, look for her mother and return to China with her. She thought that once she had become a prostitute, it was not possible… to turn back…”5

In some instances, prostitutes raised abandoned or orphaned girls as their own, and some of these girls followed in their adopted mothers’ footsteps.6 Once a girl reached puberty, she would have been taught the necessary skills by an “older sister”. During a more explicit period of training, the teenager would receive detailed instructions in the arts of lovemaking and massage. She would also learn how to use aphrodisiacs and other sexual devices, and how to entertain and pleasure men from sex manuals, erotic paintings and pamphlets.

Once the girl, usually between the ages of 13 and 15, completed her apprenticeship, her virginity would be sold to the highest bidder: men would pay several hundred dollars to more than a thousand dollars for the experience of deflowering her.7

The Brothels

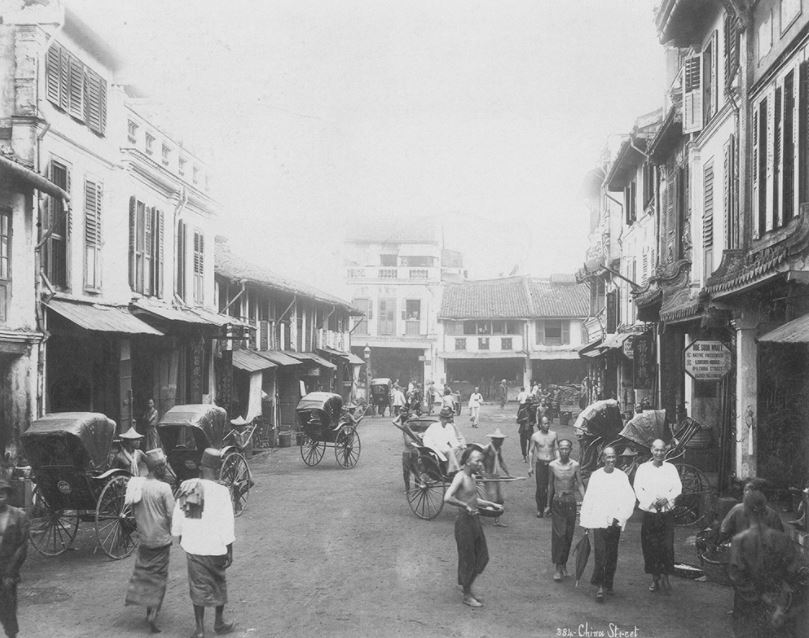

The men who frequented brothels in Singapore were a mixed bag that included “sons of towkay, bank clerks, street hawkers, rickshaw pullers, high-ranking officials, restaurant proprietors, colonial soldiers, and denizens of the underworld”.8 These men could have their pick from any of the many brothels that lined certain streets cheek by jowl.9

“Each of the districts… had their local clients… Europeans – diplomats, officials and planters – favoured the discreet Japanese women of Malay and Malabar Streets. Foreign tourists, soldiers, and, especially Japanese sailors also sought their sexual favours by visiting the unregistered haunts of Malay and Eurasian women scattered in the side lanes and alleys of the city. Rickshawmen made regular journeys to the brothels in Chin Hin Street, Fraser Street, Sago Street, Smith Street, Tan Quee Lan Street and Upper Hokien Street.”10

Japanese prostitutes, known as karayuki-san, operated within the Japanese enclave along Hylam, Malabar, Malay and Bugis streets where Japanese merchants, shopkeepers, doctors and bankers had set up shop. By 1920, the Japanese community in Singapore was large and thriving enough to host its own newspaper, the Nanyo Shimpo, a Japanese cemetery and a Japanese school.11

In the Kreta Ayer/Chinatown area, Chinese brothels catered to a largely different clientele. In addition to brothels that served the average worker, there were high-class ones that were visited by rich patrons who had their favourite prostitutes.

Historian James Warren’s in-depth study of life in Singapore brothels pieced together the practices of women in the profession by, among other things, examining information from coroner’s records and inquests as well as interviewing people who lived close to where the brothels were. His research unveiled intimate details such as how older women in the brothel prepared virgins for their first sexual experience. Warren also learned of their beauty secrets that included washing one’s face with powder ground from raw rice instead of cheap scented soap.

Some of these sex workers managed to escape the trade: a few were able to save enough money to pay their way out of brothels while others were bought by wealthy businessmen and ended up as their mistresses or concubines.12 The latter were a minority though; for most, prostitution was a lifetime prison sentence until they met with illness or death.

Warren’s research uncovered shocking accounts of sex workers dying because of venereal disease, fatal fights resulting from social rivalry, alcoholism and drug abuse. Many prostitutes committed suicide – by overdosing on opium or ingesting poison, or by hanging or slitting their throats and, in one gory account, being burnt alive – because they had no chance of ever leaving the brothel. Death provided release from poverty, debt and ill health.13

One account by Chu Ah Tan, a brothel owner, recounted the desperation experienced by a prostitute struggling with pulmonary tuberculosis and venereal disease. For eight years she smoked opium and injected herself with increasing dosages of morphine. She finally died after an overdose of opium.

“Wong Mau Tan was one of the prostitutes in my brothel… she was coughing a lot and said that she had a cough and headache for two months. Yesterday evening, her maidservant found her in bed, spit was coming from her mouth. I removed her to the hospital, she was conscious up to the last.”14

An Evening’s Entertainment

Why did men in Singapore visit prostitutes? For some, it was all part of business entertainment. Influential Chinese and European elites would arrange to meet in brothels to discuss business first before progressing to the evening’s entertainment.15 And it was not just the rich who thought a visit to a prostitute was normal.

Entreprenuer Choong Keow Chye recalled in his oral history account:

“I was a sinkeh earning about $10 a month. These people who won some money, $80 to $100, in gambling invited me to the brothel… Three to five dollars, or eight to ten dollars would pay for a night’s stay with a prostitute.”16

The women could not keep all this money either: they were expected to pay the brothel owner between 40 and 50 percent of their earnings for rent, secret society protection, food, tailored dresses, loan of jewellery and medical fees.17

Beyond the immediate satiation of their sexual urges, many of the thousands of men who sought comfort in the arms of prostitutes did not see marriage in their future. They were too poor and earned too little to even entertain the thought of finding a wife, either in Singapore or back in their hometowns.18 These men toiled as manual labourers, working as rickshaw pullers, coal shovellers, construction workers and coolies, and led a tough life with little or no means of leisure. Apart from work, these men were lonely and many led a meaningless existence without companionship.

Prostitution naturally brought with it a host of social ills. The demand for paid sex was a lucrative source of revenue for brothel owners and especially for the secret societies that controlled the brothels, and hence any threat to this business would have serious consequences. Secret societies frequently fought one another over control of the brothels and the women.

Sex workers were also a conduit for sexually transmitted diseases. This was a problem that pervaded all classes of society. Even the wealthy who patronised the more expensive brothels on Smith Street under the misconception that the women there were more discriminating, and thus safer, were not exempt. These men then – either knowingly or unknowingly – passed on sexually transmitted diseases to their wives and concubines.

Despite the many social problems associated with prostitution, the colonial authorities tolerated and legalised the trade in the early years, partly due to the low female-to-male population ratio in Singapore.

Protecting Girls and Women

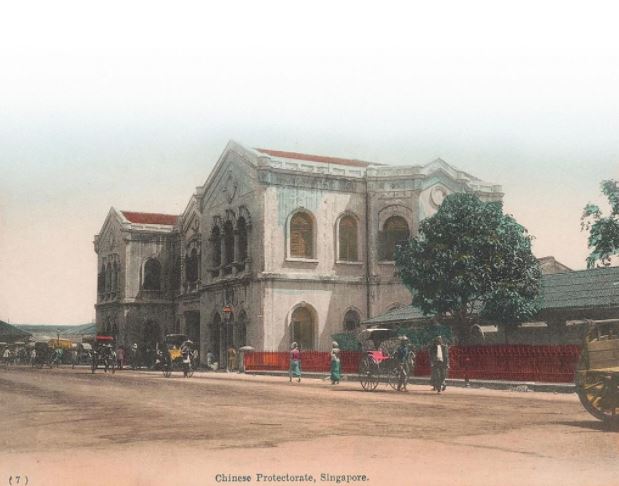

The government, however, did help young girls and women who were trafficked into prostitution. This task was initially handled by the Chinese Protectorate, which was set up in 1877 under colonial administrator William Pickering. The Protectorate managed the affairs of the migrant Chinese community.

In 1888, the Protectorate set up a separate body, the Po Leung Kuk, or the Office to Protect Virtue, to help women who had been sold or tricked into prostitution. The Po Leung Kuk also functioned as a halfway house for young girls such as the mui tsai that it helped rescue from abuse.

The mui tsai (literally “little sister” in Cantonese) were girls as young as eight years old who came to Singapore, accompanying a relative or a fellow villager. The girls came to seek a better future through marriage or employment as domestic workers. However, many of these girls ended up being tricked into prostitution, or sold to rich families who might abuse them.

As the mui tsai grew into her teens, her situation could worsen: if she was pretty, she would find herself servicing the sexual needs of the male members in the household; if she were to bear children, she would not be allowed to claim or acknowledge them until her mistress passed away.19 The Po Leung Kuk rescued these girls, gave them a safe place to live and trained them in useful skills that could help them find decent men to marry or a useful job when they left the Po Leung Kuk.

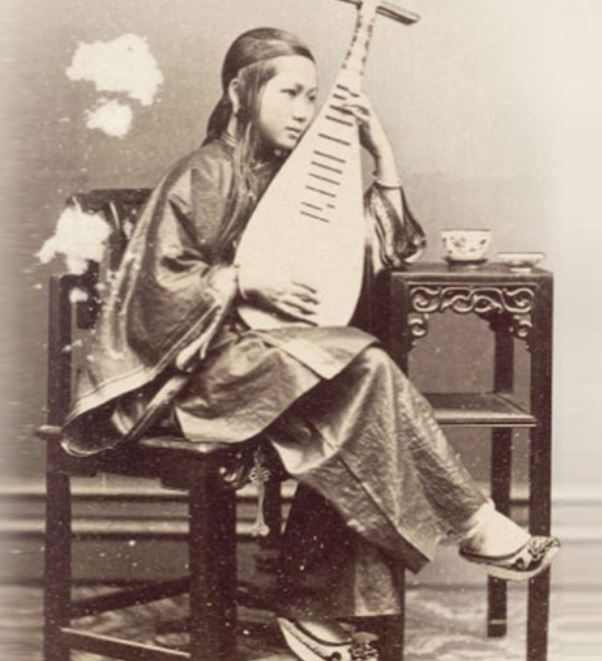

Another group of young girls who were rescued by the Po Leung Kuk was the pipa tsai. These were girls who were trained to play and sing to the accompaniment of the pipa, a short-necked wooden lute. In brothels and clubs where men gathered, these girls entertained their clients by reciting Chinese poetry and bantering with them. The older among the pipa tsai would be made to sit at tables to accompany men. These girls were paid by the hour and sometimes also provided sexual services.

How did these pipa tsai enter such employment? Like the mui tsai, they had been entrusted by their parents in China to the care of distant relatives in Singapore, the so-called “third or sixth paternal aunt” – sum gu orluk gu – some of whom worked in or even owned entertainment establishments themselves. The pipa tsai could also have been picked out when these “aunts” visited destitute women and their young daughters living in shelters such as temples.

Girls who had been forcibly controlled and detained by these aunts could escape their bondage only after they had outlived their popularity or if they were able to find married men who were willing to buy them out of their pipa-playing employment.20 The more fortunate girls were rescued by the authorities and taken in by the Po Leung Kuk. But this was a temporary arrangement: the future of these girls depended on whether they could learn new skills and find suitable jobs after leaving the Po Leung Kuk.

The Cabaret Scene

When the glitz and glamour of the 1920s Shanghai nightclub scene spilled over to Singapore, it brought with it the promise of a different life, at least for some of the women who struggled to make a new life for themselves after they had left or broken free from sexual slavery and bondage.

The women who chose to step into Singapore’s budding cabaret scene could now take control over their lives. Dancing in a cabaret paid relatively well, and was filled with music, alcohol and laughter. They could doll up and use their feminine wiles to manipulate men, unlike the subservient mui tsai, pipa tsai or brothel worker who had to endure servitude, slavery and indignity.

As cabarets and nightclubs burgeoned in Singapore,21 women who lacked education or skills were able to seek out more enticing employment opportunities, beyond just prostitution. This is not to say that prostitution disappeared; not everyone had the attributes of a cabaret girl. For those who did not, the flesh trade continued to be an option.

Because of the lowly status of women and the stigma around sex work, the lives of prostitutes in late 19th- and early 20th-century Singapore are typically given scant attention. However, they are an important part of Singapore’s social history, as historian James Warren has noted: “Much of the history of Singapore between 1870 and 1940 was in part shaped, and in large measure endured, by prostitutes and coolies.”22

THE OFFICE TO PROTECT VIRTUE

The Po Leung Kuk was set up in Singapore in 1888, about 10 years after it was first established in Hong Kong. The Po Leung Kuk, or the Office to Protect Virtue, was created to offer protection to girls who had been sold or lured into prostitution.

In Singapore, the Po Leung Kuk also provided protection and assistance for the repatriation of women and girls to China. Its other role was to supply marriage partners to a predominantly male population who did not have the means to find a bride from their village.

In addition to housing girls rescued from prostitution, the Po Leung Kuk took in young female servants known as mui tsai if they had been abused.23 The Po Leung Kuk also functioned as a “halfway house”, offering shelter, food and training to rehabilitate girls. Once the residents turned 18, they were eligible for marriage. All applications made to the Po Leung Kuk by men to select brides were carefully screened and approved by the management committee.

The Po Leung Kuk had its beginnings in Lock Hospital in the Kandang Kerbau area, moving subsequently to larger premises on York Hill in Chinatown which could accommodate as many as 300 residents.24

Women who were rescued and rehabilitated by the Po Leung Kuk were sought after as wives as they were trained in domestic service, and acquired skills such as dressmaking and hairdressing that could help supplement their husband’s income.25

Life for the residents of Po Leung Kuk seemed to be a pleasant one, if a visitor’s impression in 1936 is any guide:

“The walls of the main schoolroom which is a large cheerful apartment are gaily decorated with pictures drawn and painted by the pupils themselves. The children are educated in accordance with Chinese custom, and the bigger girls are taught the arts of fine sewing and embroidery. With few exceptions, the girls are all under eighteen, and they appeared so happily carefree that I found it difficult to believe they had ever suffered unkind treatment or neglect.”26

In Singapore, the Po Leung Kuk’s management committee was chaired by the Protector of Chinese and a body of 13 influential Chinese businessmen. The activities of the Po Leung Kuk were supported by government funds and private donations.27

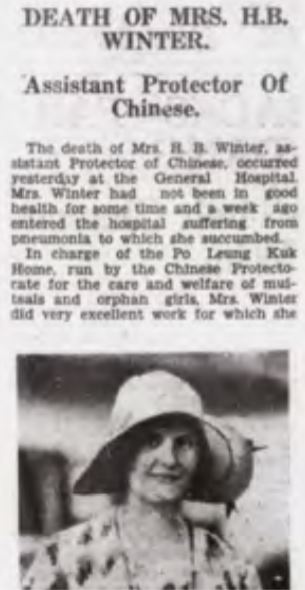

On 1 March 1929, Mrs Mabel Winter was appointed the first Lady Assistant Protector of Chinese.28 She took over the management of Po Leung Kuk’s day-to-day operations and was assisted in her duties by a committee of ladies.29

Winter’s appointment as Lady Assistant Protector of Chinese was significant as it was the first time a woman had been given such an important post, signifying the serious intent of the British, or at least the Chinese Protectorate, to rescue and rehabilitate women and girls from prostitution and slavery.

Mabel Winter was the wife of Mr H.B. Winter, the proprietor of a well-known tailoring establishment on Battery Road. She had been born in Hong Kong where “she learned to speak Chinese so fluently that the Chinese expressed astonishment at her complete mastery of the language”.30

She married in Colombo in 1915, where her husband had served in the Fifth Gurkhas regiment.31Unfortunately, Winter’s time at the Po Leung Kuk was cut short when she died from pneumonia on 25 January 1934 and was buried in Bidadari Cemetery.32 She was only 42.

To remember her contributions, the Mabel Winter Memorial Shield was set up and given out annually to an outstanding candidate in the Po Leung Kuk who excelled in needlework and cooking and displayed exemplary conduct.33

From the 1930s, the number of women and girls admitted to the Po Leung Kuk in Singapore fell. One researcher suggests that this was due to the implementation of the 1930 Women and Girls’ Protection Ordinance that outlawed brothels and vice activities. Unfortunately, the legislation sent brothels underground and made it harder to track and rescue women who needed help.34 In 1932, the Mui Tsai Ordinance was introduced to prohibit the acquisition ofmui tsai; this would, in time, also reduce the number of girls that needed to be rescued.

During the Japanese Occupation, the Po Leung Kuk’s premises were abandoned and its residents dispersed to several welfare centres. When the British Military Administration took over after the war, the new Department of Social Welfare was set up, and the Po Leung Kuk was closed.35

Adeline Foo

is a scriptwriter and an adjunct lecturer. Her research interests include women, and societal prejudice and discrimination. She is the researcher and creator of Last Madame, a drama series about the 1930s brothel scene in Singapore. The show debuted in September 2019 on MediaCorp Toggle.

Adeline Foo

is a scriptwriter and an adjunct lecturer. Her research interests include women, and societal prejudice and discrimination. She is the researcher and creator of Last Madame, a drama series about the 1930s brothel scene in Singapore. The show debuted in September 2019 on MediaCorp Toggle.

Notes

-

Warren, J.F. (2003). Ah ku and karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870–1940 (p. 212). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.74095957 WAR) ↩

-

Turnbull, C. M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (p. 101). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

我是一個妓女. (1940, October 25). 《南洋商报》 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Heritage Committee. Japanese Association. (1998). Prewar Japanese community in Singapore: Picture and record. Singapore: Japanese Association, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 305.895605957 PRE) ↩

-

Lim, H.S. (Interviewer). (1980, February 5). Oral history interview with Choong Keow Chye 钟桥才 [Transcript of recording no. 000015/2/1, p. 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Koh, C.C. (1994). Implementing government policy for the protection of women and girls in Singapore: Recollections of a social worker (p. 125). In M. Jaschok & S. Miers. (Eds.). (1994). Women & Chinese patriarchy: Submission, servitude, and escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press: London; Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Zed Books. (Call no.: RSING 305.420951 WOM) ↩

-

See Adeline Foo’s essay, Beneath the Glitz and Glamour: The Untold Story of the “Lancing” Girls, published in BiblioAsia, 12(4), Jan-Mar 2017. ↩

-

Little maid-of-all-work tells sad story. (1933, October 13). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Paul, G. (1990). The Poh Leung Kuk in Singapore: Protection of women and girls (p. 17) [Unpublished undergraduate thesis, National University of Singapore]. Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RCLOS 305.42095957 PAU); Chinese affairs in Malaya. (1932, April 14). The Straits Times, p. 19; Chinese topics in Malaya. (1932, September 22). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A woman’s notebook. (1936, January 23). The Straits Times, Women’s Supplement, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Levine, P. (2003). Prostitution, race, and politics: Policing venereal disease in the British Empire (p. 214). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: R 306.740941 LEV) ↩

-

Death of Mrs H.B. Winter. (1934, January 26). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lady Assistant Protector of Chinese. (1934, January 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 26 Jan 1934, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 26 Jan 1934, p. 13. ↩

-

Po Leung Kuk at home. (1937, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩