Planning to Build, Building to Plan

The collection of building plans in the National Archives of Singapore is a treasure trove of information about the history of urban Singapore, says Yap Jo Lin.

This 1908 plan of a mock Tudor-style house in Tanglin for T. Sarkies was featured in Lee Kip Lin’s The Singapore House. It was described as a “fine example of the beautiful rendering that was characteristic of the period” (9131/1908). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This 1908 plan of a mock Tudor-style house in Tanglin for T. Sarkies was featured in Lee Kip Lin’s The Singapore House. It was described as a “fine example of the beautiful rendering that was characteristic of the period” (9131/1908). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In Pastel Portraits, a book documenting Singapore’s pre-war architecture, editor and author Gretchen Liu writes that “it is difficult to imagine a city of such homes today but the building plans housed in National Archives’ records centre give some indication of the variety and richness of these homes, from the more humble single-storey kampong house with Malay fretwork eaves built on low brick piers with a front verandah, to the elaborate two-storey villas with Venetian windows, Corinthian style columns and ornate plasterwork”.1

Liu was referring to the collection of building plans held by the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) that date back to the late 19th century. At the heart of this building plan collection is the Building Control Division (BCD) Collection, which consists of around 246,000 plans prepared between 1884 and 1969.2 These were submitted for approval as part of the government’s effort to ensure that buildings erected in Singapore were structurally sound. Although only a handful of these plans have been digitised, the collection has been microfilmed and can be accessed at the Archives Reading Room in the NAS building.

The collection is a valuable resource for those interested in Singapore’s architectural history. In his book on black-and-white houses, architectural historian Julian Davison notes that “several months of winding through furlongs of microfilm” produced a more complete picture of black-and-white houses. Earlier publications on black-and-white dwellings only focused on houses built by the Public Works Department.3

The hand-drawn shading on the plans – especially plans depicting planned additions and alterations to a building – are also useful for historical research. As the shading conveys the extant parts of the structure at the time of planning, it provides important clues to a building’s history. Such clues allow for more sensitive preservation work, especially when the intention is to restore the buildings to their original condition.

Beyond the buildings themselves, the plans hint at the surrounding area as well, providing an invaluable glimpse into a constantly changing Singapore. As Liu notes in Pastel Portraits, “[n]early all of the early plans have these roughly drawn maps [key plans or site plans] which give countless clues to the growth and development of the city”.4

Hidden Gems

Considering that these building plans were drawn up to fulfil a prosaic function, their beauty is often surprising. The intricacy of the hand-drawn and hand-coloured detail is stunning, especially compared to the computer-generated imagery of today. One plan for a mock Tudor-style house has been described by the architect Lee Kip Lin as “a fine example of the beautiful rendering that was characteristic of the period”.5 The plan was reproduced in Lee’s landmark 1988 publication, The Singapore House, 1819–1942.

Most of the plans belonging to the BCD, a predecessor of today’s Building and Construction Authority, reflect the stamp of the approving authority of the day, whose names mirror the changes in Singapore’s governing administrative body. In the initial years, the plans were approved by various entities within the Municipal Office such as the Municipal Engineer’s Office, the Municipal Architect’s Office and the Municipal Building Surveyor’s Office.

Following the reconstitution of the Municipal Commission into the City Council in 1951, the approving authority became the City Council’s Architect and Building Surveyor’s Department the following year. The next major changes took place in the 1960s. Following the dissolution of the City Council in 1959, the stamp “City Council of Singapore, Chief Building Surveyor’s Department” was replaced with “State of Singapore, Chief Building Surveyor’s Department”. After Singapore gained independence in 1965, “State of Singapore” was replaced with “Republic of Singapore”.

The earlier building plans in the collection bear the signatures of various municipal engineers and municipal commissioners who, fittingly enough, continue to be memorialised in Singapore’s landscape. These individuals include Henry Edward McCallum (McCallum Street), James MacRitchie (MacRitchie Reservoir), Alfred Howard Vincent Newton (Newton Road and Newton Circus), Samuel Dunlop (Dunlop Street), Alex Gentle (Gentle Road) and Samuel Tomlinson (Tomlinson Road).

These building plans are also a testament to early attempts to keep track of Singapore’s built environment. It appears that a survey of sorts was conducted in the 1930s and 40s to ascertain the state of the buildings after their plans had been approved. As a result, many of the plans in the BCD Collection bear the records of one “V S Rasiah”, whose notes included an updated address for a building, whether the building had actually “not (been) erected”, or (sadly) if the building had been “demolished” or was “not in existence”. Unfortunately, there is no further information about this person.

A Variety of Building Types

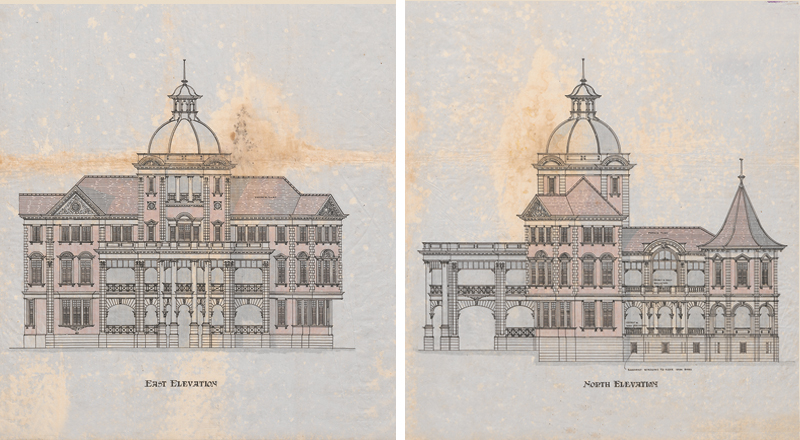

Given that any private application to erect a building in Singapore had to be submitted to the authorities, the plans in the BCD Collection cover a wide array of building types. A prime example is the set of building plans for Eu Villa – the lavish Mount Sophia residence of Chinese businessman and community leader Eu Tong Sen.6 Eu is best remembered as the man behind traditional Chinese medicine purveyor Eu Yan Sang, which still exists today. His name also lives on in the busy Chinatown thoroughfare named after him – Eu Tong Sen Street. Eu commissioned architectectural firm Swan & Maclaren to build Eu Villa. The palatial property was designed in a melange of European styles, with its most prominent feature being the Renaissance-style dome, topped with a cupola, on the main building. Over the years, Eu submitted plans to make improvements to his mansion, including one in 1923 for kennels for his pet dogs.

The 1913 building plan of Eu Tong Sen’s Eu Villa showing the east and north elevations (1413–7/1913). Below that is an aerial view of the villa on Mount Sophia, 1940s. Eu built up Eu Yan Sang, a company specialising in traditional Chinese medicine set up by his father Eu Kong, into a very successful business. Building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; aerial view of Eu Villa courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; portrait of Eu Tong Sen reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 332). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

The 1913 building plan of Eu Tong Sen’s Eu Villa showing the east and north elevations (1413–7/1913). Below that is an aerial view of the villa on Mount Sophia, 1940s. Eu built up Eu Yan Sang, a company specialising in traditional Chinese medicine set up by his father Eu Kong, into a very successful business. Building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; aerial view of Eu Villa courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; portrait of Eu Tong Sen reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 332). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

The houses built for a L.R.M.R.M. Veerappa Chitty are described in The Singapore House as “typical of the kind that proliferated particularly in the suburbs of Katong, Geylang and Serangoon”.7 The plan he submitted was for three bungalows, which were raised on low piers and topped with a sloped roof. Each bungalow had three bedrooms with ensuite bathrooms, and a rear passageway leading to the kitchen and servants’ quarters.

The building plans of commercial properties in the BCD Collection include office buildings, luxury hotels and the occasional cinema and department store. A 1909 plan from the collection is for proposed alterations to the Alhambra cinema on Beach Road. Its floor plan is immediately recognisable although a “band space” had been included, possibly to provide musical accompaniment in the era of silent films.

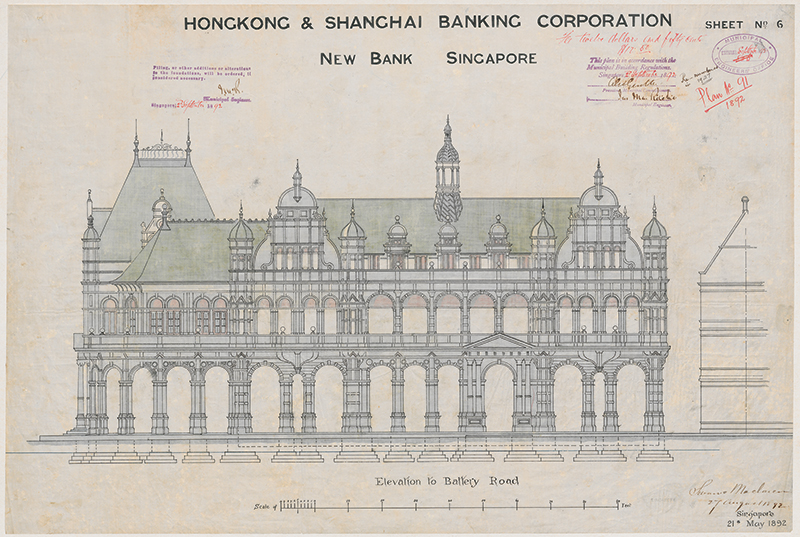

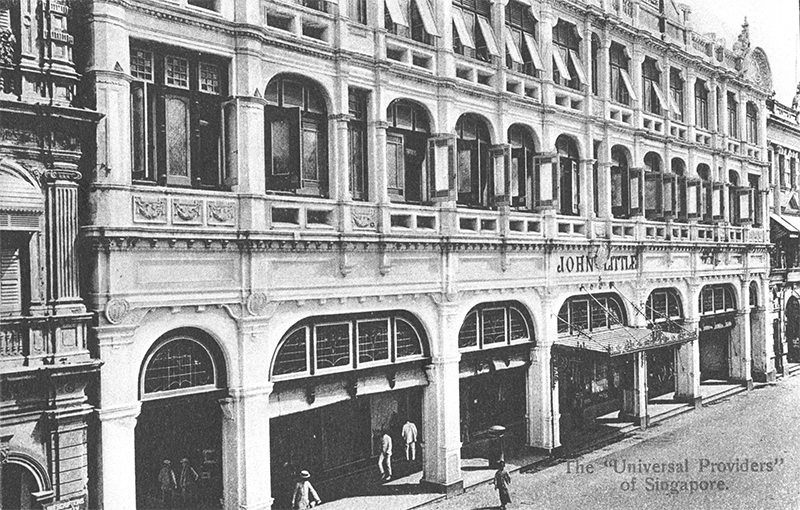

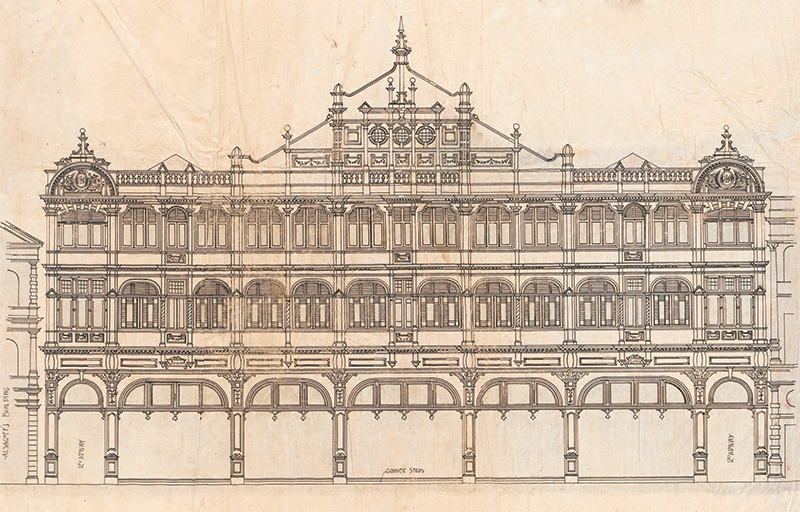

The BCD Collection is also a good starting point to research old places in Singapore such as Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). It allows one to see in greater detail buildings that no longer exist like the former Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation building and the John Little department store. Although both structures have been demolished, the facade of John Little is memorialised in the entrances of Raffles Place MRT station.

The plan of the long-demolished Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building in Collyer Quay shows the elevation to Battery Road, 1892 (91/1892). Building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The plan of the long-demolished Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building in Collyer Quay shows the elevation to Battery Road, 1892 (91/1892). Building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

John Little department store after the rebuilding of their Raffles Place premises, c. 1910. Established in 1842, the brand lasted 174 years. Its last store was shuttered in 2016. The plan shows the front elevation of the building, 1908 (9261–9/1908). Photo from the Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

John Little department store after the rebuilding of their Raffles Place premises, c. 1910. Established in 1842, the brand lasted 174 years. Its last store was shuttered in 2016. The plan shows the front elevation of the building, 1908 (9261–9/1908). Photo from the Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

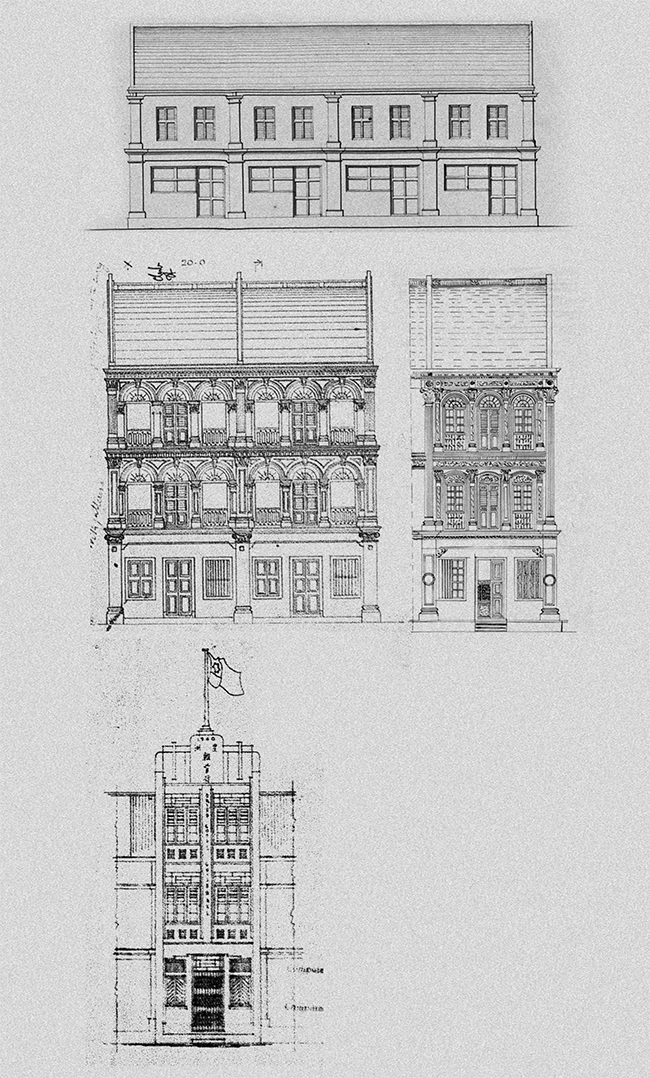

From the BCD Collection, one can also track the evolution of shophouse design in Singapore, from the earlier iterations at the start of the collection in 1884 to the subsequent “Chinese Baroque” style in the early 1900s and Art Deco-inspired style from the 1930s. Shophouse plans from the late 1800s were generally for two-storey buildings with minimal or no decorations on their facade. At the turn of the 20th century, these somewhat prosaic shophouses gave way to three-storey buildings with elaborate plasterwork, fanlights and pilasters. As the 20th century progressed, shophouse facades reverted to the stripped down simplicity of Art Deco and other modern styles.8 These shophouse plans showcase the talents of local architects and architectural firms such as W.T. Moh, Yeo Hock Siang, Loh Kiam Siew, W.T. Foo, and Almeida & Kassim. W.T. Moh designed many of the shophouses in Emerald Hill, which is today a gazetted conservation area.

Finally, there are building plans of social, cultural and religious spaces, such as schools, temples, mosques and churches. One example is the plan for an attap mosque on Tanglin Road built for a Haji Abdulrahman Glas in 1911. The mosque is a simple structure raised on stilts, with a generous open-air verandah in front that takes up more than a quarter of the building’s length.

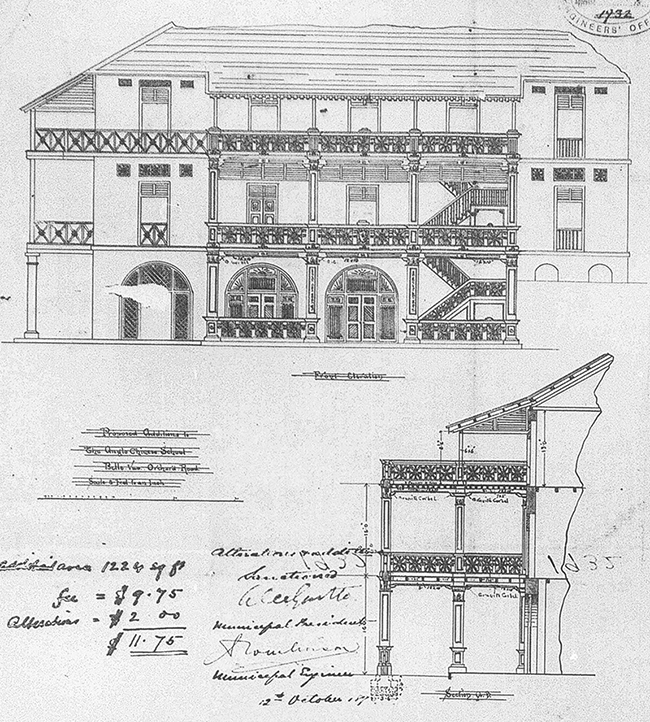

The collection also has building plans for the boarding house of Anglo-Chinese School. Known as Bellevue, it was sited near present-day Plaza Singapura. Bellevue was renamed Oldham Hall in 1902, in honour of Bishop William Fitzjames Oldham who founded the school in 1886. Oldham Hall still exists as a boarding house, but it is now situated near the school’s Barker Road premises.9

Oldham Hall (formerly known as Bellevue and occupying a site near Plaza Singapura), was the boarding house for Anglo-Chinese School, 1900s. The plan shows the front elevation and sectional view, 1896 (211–2/1896). Photo courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Oldham Hall (formerly known as Bellevue and occupying a site near Plaza Singapura), was the boarding house for Anglo-Chinese School, 1900s. The plan shows the front elevation and sectional view, 1896 (211–2/1896). Photo courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Building Plans of 1884

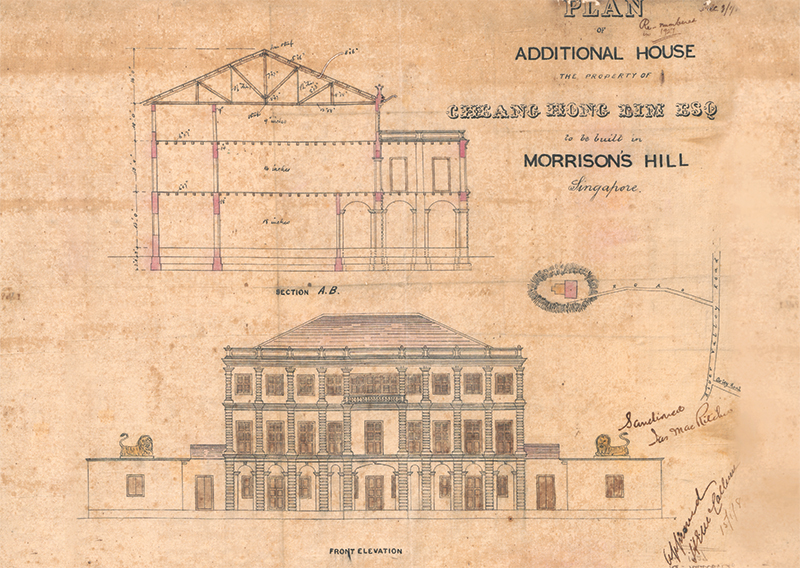

As the earliest building plans in the BCD Collection date to 1884, it is interesting to look at some of the 107 plans that were submitted that year. The earliest plan in the collection is for a house on Morrison’s Hill – an area in the vicinity of River Valley Road and Martin Road, and a locale (then and now) of high-end residences.10 The plan was submitted by Cheang Hong Lim, the businessman and philanthropist after whom Hong Lim Park is named. The plan shows a three-storey house flanked on either side by what looks like statues of lions, their tails raised in artful symmetry.

Plan of a house on Morrison’s Hill for Cheang Hong Lim, 1884 (1/1884). This is the earliest plan in the Building Control Division Collection. Cheang (below) was a businessman and philanthropist after whom Hong Lim Park is named. Portrait of Cheang Hong Lim from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Plan of a house on Morrison’s Hill for Cheang Hong Lim, 1884 (1/1884). This is the earliest plan in the Building Control Division Collection. Cheang (below) was a businessman and philanthropist after whom Hong Lim Park is named. Portrait of Cheang Hong Lim from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore; building plan from the Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Other notable personalities who applied to make various additions to their properties that year include Chinese merchants Tan Quee Lan, Hoo Ah Kay (better known as Whampoa)11 and Low Kim Pong.

Tan Quee Lan, who has a street named after him, applied to build a two-storey house on the now expunged Rama Street – near where Club Street and Mohamed Ali Lane meet today. The house has an unusual triangular-shaped floor plan, explained by its location on a similarly shaped plot of land at the junction of two roads.12

Whampoa’s building plan was for an additional storehouse to be constructed on Havelock Road, across the road from his bakery. This famous establishment was mentioned in Song Ong Siang’s seminal work, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, as being “for many years the most extensive in the Colony”.13

Low Kim Pong – who is best known for having provided land and funding for the construction of the Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery in Toa Payoh14 – was the most ambitious of the three merchants in 1884. That year, he made three separate applications to build six shophouses, one shop, one timber depot and additions to two stables. However, a note on the building plan of the shop and stables indicates that by 1931, these structures were “not in existence”.

There are two building plans in the collection attributed to one or two men with the surname Desker for new developments on Waterloo Street: one for a dwelling for a Mr Desker and another for six houses for a Mr H. Desker. It is possible that the Desker in question refers to either Andre Filipe Desker, a very successful Eurasian butcher after whom Desker Road is named, or his son Armenisgild Stanislaus Desker, who is known to have lived on Waterloo Street. Andre Filipe Desker was also known as Henry Filipe Desker, so the plan for the six houses was most likely submitted on his behalf.15

The New Harbour Dock Company, which was based at New Harbour (now known as Keppel Harbour), submitted three building plans in 1884 – for an addition to an engine house, a “quarter” and for a “property” (most likely a house). The engine house plan is meticulously drawn and coloured, with fanlights added above the doors and windows to enhance the aesthetics of the building. The other two plans are simpler in design and depict what look like basic wooden structures. (The New Harbour Dock Company subsequently merged with another private operator, the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, and eventually became the Port of Singapore Authority.16)

The plan for an addition to an engine house for the New Harbour Dock Company, 1884. (86/1884). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The plan for an addition to an engine house for the New Harbour Dock Company, 1884. (86/1884). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Shophouse Design

The majority of the building plans submitted in 1884 were residential in nature. Almost half of the plans were for shophouses, the architectural style of which was relatively simple.

One example is the plan for a row of shophouses along Beach Road. The front elevation shows a simple facade, with a five-footway that is more visible from the sectional plan. The plan includes a skylight to let in much-needed light and air into the house. The air-well below the skylight has a sunken floor to collect rainwater that would have come through the opening.

While rudimentary facades were the norm for shophouses built in 1884, there are two building plans depicting more elaborate ornamentation. One was for a row of shophouses along Serangoon Road, each adorned with a pair of thin minarets, while the other was for a shophouse on Trengganu Street that had extended eaves designed along the style of Malay wooden fretwork.

The front elevations of these four shophouses demonstrate how this type of building evolved between 1884 and 1940 (50/1884, 228/1896, 3749/1900, 93C/1940). The design in 1884 (top row) shows a simple two-storey building with minimal or no decorations on the facade. By the 1900s, these minimalist shophouses had evolved to become three-storey buildings with elaborate plasterwork, fanlights and pilasters (middle row). In the 1940s, shophouses were designed in the Art Deco style (bottom row). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The front elevations of these four shophouses demonstrate how this type of building evolved between 1884 and 1940 (50/1884, 228/1896, 3749/1900, 93C/1940). The design in 1884 (top row) shows a simple two-storey building with minimal or no decorations on the facade. By the 1900s, these minimalist shophouses had evolved to become three-storey buildings with elaborate plasterwork, fanlights and pilasters (middle row). In the 1940s, shophouses were designed in the Art Deco style (bottom row). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Other Building Designs from 1884

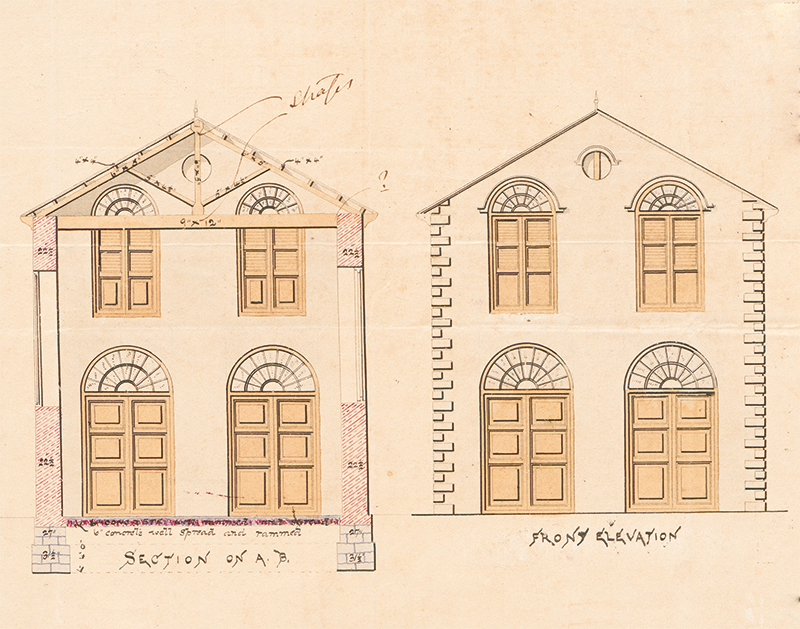

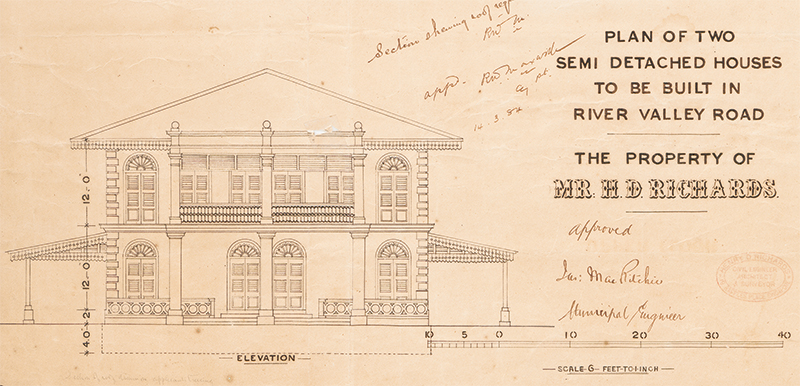

About a quarter of the plans were for other types of houses, which ranged from simple structures raised above ground in the style of traditional Malay houses to grander affairs like the pair of semi-detached houses on River Valley Road for Henry D. Richards. Richards was a civil engineer and surveyor, and the plan bears his official stamp at the bottom right corner.

The floor plan of Richards’ house shows a terrace and portico on the ground floor, and two verandahs above – for residents to enjoy the breeze. The main entrance opens to a long corridor leading to a dining room on the ground floor, while the drawing room or living room is on the second floor. The main house has three bedrooms and one bathroom, with an outhouse at the back for the kitchen and rooms for servants. The building plan also features a stall, a carriage shed and a room for the syce (a groom or stable attendant).

The front elevation plan of two semi-detached houses on River Valley Road for Henry D. Richards, 1884 (25/1884). Richards was a civil engineer and surveyor, and the plan bears his official stamp at the bottom right corner. Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The front elevation plan of two semi-detached houses on River Valley Road for Henry D. Richards, 1884 (25/1884). Richards was a civil engineer and surveyor, and the plan bears his official stamp at the bottom right corner. Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Buffaloes and horses were essential means of transportation in the late 19th century. Quite a number of the 1884 building plans include housing for animals; eight plans specifically mention carriage sheds, stalls and stables in their titles. The plan for Desker’s house on Waterloo Street also includes a section labelled “Fowl House”. Rather worryingly, this is located between the bathroom and the water closet – both presumably for humans.

Another example of the reliance on animals during this period can be seen in the plans to build a carriage shed and bullock and pony stalls near the junction of Serangoon Road and Buffalo Road. This was a popular place for cattle rearing because nearby water sources like the Rochor River provided bathing areas for water buffaloes.17

Only one of the plans submitted in 1884 was for a school, “to be erected in the compound of the Church of St Jose”, present-day St Joseph’s Church on Victoria Street. The school in question was actually a new building for St Anna’s School, the predecessor of St Anthony’s Convent.18 Based on the school’s site plan, it was to have been located at the junction of Middle Road and Queen Street.

A Valuable Resource

The aesthetic quality of the building plans, their breadth and comprehensiveness, and the fact that they represent close to a century’s worth of Singapore’s urban and architectural history make the BCD Collection valuable and unique. Many writers, scholars, architects and historians have conducted research using the collection. One recent publication featuring the BCD Collection is a history of Swan & Maclaren by Julian Davison.19 There are undoubtedly more gems waiting to be uncovered, especially when explored together with other resources of the National Archives of Singapore and at the National Library.

| STREET NAMES |

| The street names seen in the 1884 plans are, for the most part, similar to the street names of today, especially those that reference common English words like North Bridge Road or Beach Road. |

| There is more variation in names that have Malay origins. Kallang is spelt as Kalang, Serangoon is spelt as Serangong or Sirangoon, Trengganu is spelt as Tringanu. Bras Basah is spelt as Brass Bassa or Brass Bassah; Brass Bassa was the official name until it was formally changed in 1899. One plan for a shophouse mentions a street name that has changed entirely since 1884 – Kling Street, the old name for Chulia Street. The road was renamed in 1922 in response to objections from the Indian community that the original name was derogatory. |

| REFERENCES |

| National Library Board. (2017). Chulia Street written by Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman & Vernon Cornelius. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. |

| Untitled. (1899, June 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

Yap Jo Lin is an Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. Her portfolio includes taking care of the archives’ collection of building plans.

Yap Jo Lin is an Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. Her portfolio includes taking care of the archives’ collection of building plans.

NOTES

-

Liu, G. (1984). Pastel portraits: Singapore’s architectural heritage (p. 147). Singapore: Coordinating Committee. (Call no.: RSING 722.4095957 PAS) ↩

-

The other building plans in the collection of the National Archives include those transferred from other government agencies as well those given by private donors. ↩

-

Davidson, J. (2014). Black and white: The Singapore house, 1898–1941 (p. 2). Singapore: Talisman. (Call no.: RSING 728.37095957 DAV) ↩

-

Lee, K.L. (2015). The Singapore house, 1819–1942 (p. 66). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions and National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 728.095957 LEE) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014, September 15). Eu Tong Sen written by Alex Chow. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; Seow, P.N. (2016, Jul–Sep). Eu Tong Sen and his business empire. BiblioAsia, 12 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2018, April). Your shophouse: Do it right. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). William F. Oldham written by Bonny Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; ACS Oldham Hall. (2018). History. Retrieved from ACS Oldham Hall website. ↩

-

Lee, 2015, p. 115; Survey Department, Singapore (1893). Plan of Singapore town showing topographical detail and municipal numbers [Survey map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2019, August). Hoo Ah Kay written by Bonny Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Interestingly, this building plan bears the rubber stamp of the architects and surveyors, Lermit & Annamalai. Alfred Lermit eventually went on to partner with engineer Archibald Swan who, in turn, set up Swan & Maclaren with civil engineer James Waddell Boyd Maclaren in 1892. The firm is Singapore’s oldest architectural practice today and it celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2017. ↩

-

Song, O.S. (2020). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore [electronic resource]: The annotated edition (p. 75). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. Retrieved from OverDrive. (myLibrary ID is required to access this ebook) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014, December 12). Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery (Siong Lim Temple) written by Kaylene Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Desker Road written by Vernon Cornelius & Faridah Ibrahim. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; Local and general. (1893, January 24). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3; Page 2 Advertisements Column 1: In the goods of. (1901, January 22). The Singapore Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2015, December). Singapore Harbour Board (1913–1964) written by Joanna Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; Wee, B.G. (2019, Jul–Sep). The story of two shipyards. BiblioAsia, 15 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2019, January 30). Little India - A cultural and historical precinct. Retrieved from Roots website. ↩

-

St Anthony’s Canossian Primary School. (2020). History. Retrieved from St Anthony’s Canossian Primary School website. ↩

-

Davison, J. (2020). Swan & Maclaren: A story of Singapore architecture. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and ORO Editions. (Call no.: RSING 720.95957 DAV) ↩