At Gunpoint: Wiping Out Illegal Firearms in Singapore

Street shootouts, bank robberies and armed kidnappings used to be common here. Tan Chui Hua zeroes in on how the city’s gun-toting criminals were eliminated.

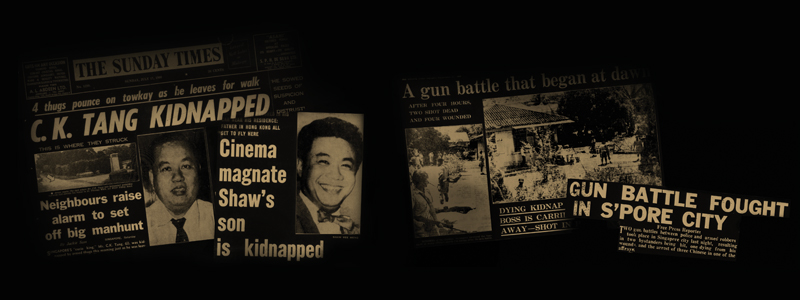

(From the left) In the 1950s and 60s, kidnappings of wealthy individuals for ransom at gunpoint occurred frequently in Singapore. The victims included “curio king” C.K. Tang and Shaw Vee Ming, the eldest son of cinema tycoon Run Run Shaw. To capture the infamous kidnapper Loh Ngut Fong in 1968, some 350 policemen and members of the Gurkha contingent were deployed. In June 1946, an innocent Indian man was accidentally killed on Robinson Road when police and armed robbers exchanged fire. The Sunday Times, 17 July 1960, p. 1; The Straits Times, 6 February 1964, p. 1; The Straits Times, 11 November 1968, p. 11; The Singapore Free Press, 19 June 1946, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

(From the left) In the 1950s and 60s, kidnappings of wealthy individuals for ransom at gunpoint occurred frequently in Singapore. The victims included “curio king” C.K. Tang and Shaw Vee Ming, the eldest son of cinema tycoon Run Run Shaw. To capture the infamous kidnapper Loh Ngut Fong in 1968, some 350 policemen and members of the Gurkha contingent were deployed. In June 1946, an innocent Indian man was accidentally killed on Robinson Road when police and armed robbers exchanged fire. The Sunday Times, 17 July 1960, p. 1; The Straits Times, 6 February 1964, p. 1; The Straits Times, 11 November 1968, p. 11; The Singapore Free Press, 19 June 1946, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

“When dawn broke, Mr Goh, using a loud hailer, warned the men inside to surrender. Repeated warnings were given as police thought a woman and child were also inside.

“A few minutes passed before Loh himself appeared at the front door. Within seconds, the lights in the house were switched off and Loh made a sudden appearance with his machine gun.

“Standing at the door, he sprayed a full magazine at the police before running back inside.

“Then began the fiercest battle in Singapore crime annals when hundreds of rounds of ammunition and scores of teargas bombs were fired into the gang’s house.”1

The battle between the police and the notorious kidnapper Loh Ngut Fong and his gang raged for several hours. It finally ended after Gurkhas stormed the house in St Helier’s Avenue that the gang was using as a hideout. Loh died clutching a light machine gun and an automatic pistol.

The shootout between Loh’s gang and the police took place in November 1968, a little more than 50 years ago. For a large part of the 20th century, Singapore was a violent and lawless city. In the post-war years especially, armed robberies, kidnappings at gunpoint and shootouts with the police were not uncommon. It was only from the 1970s onwards that effective measures to contain gun violence began to have an effect and guns became less common in Singapore.

One of the earliest accounts of the use of firearms in criminal activity is found in Charles Burton Buckley’s An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, although that was related to piracy at sea in the early 1800s.

While robbers and gangsters were responsible for many of the violent crimes committed in Singapore in the 19th century, many of the incidents involved knives rather than guns. The proliferation of firearm use on the island picked up dramatically at the turn of the 20th century and escalated sharply by the 1920s to the point that, according to The Malaya Tribune, “Singapore can be likened to notorious Chicago in that it tops the crime list in the Straits Settlements and Malaya”.2 Street shootouts and reports of police wounded or even killed in the line of duty were common.

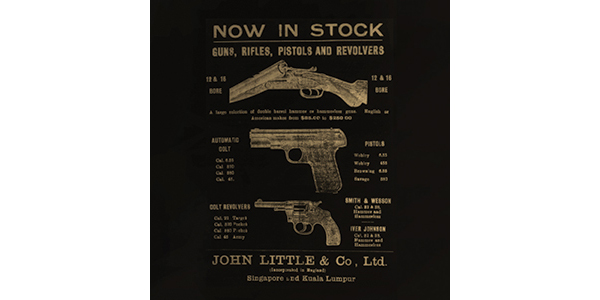

In the early 1900s in Singapore, firearms could be purchased at department stores such as John Little & Co. The Straits Times, 10 August 1920, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

In the early 1900s in Singapore, firearms could be purchased at department stores such as John Little & Co. The Straits Times, 10 August 1920, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

While guns and firearms could be legally sold in Singapore, and indeed were available in department stores such as John Little, the root of the problem lay in the unlicensed weapons that were illegally imported into the island. The situation became so severe that in 1924, The Straits Times reported that:

“… an estimate of the firearms illegally held in Singapore, among the gang robbers and secret societies, was ten thousand automatic pistols and hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition. That may be an exaggeration: we have no means of checking the estimate, but it is a fact that illegal import has been going on for several years, that very light punishments used to be inflicted, and that in spite of the more stringent law, the business continues on a quite considerable scale.”3

In 1925, The Malaya Tribune reported that guns were smuggled in from ships and “in this way hundreds of revolvers and pistols find their way into the Colony. Armed with these weapons gang robberies and murders have been frequent in all parts of the island; the thickly populated Chinatown being the happy hunting ground”.4

Matters were not helped by an understaffed and ill-equipped police force, with limited means to stem firearms trafficking or take down large armed gangs, especially Chinese secret societies. These triads, with their widespread membership, were responsible for many of the violent crimes committed in Singapore. René H. Onraet, Director of Criminal Intelligence and later Inspector-General of the Straits Settlements Police, wrote in 1928 that “no phase of Singapore criminal life has shown such rapid development as the use of firearms and the advent of the gunman”.5

In 1939, according to The Straits Times, “[i]t is estimated that there are in Singapore alone 170 secret societies with 15,000 members. These societies have degenerated into dangerous hooligan gangs which were, to a great extent, responsible for the abnormal increase in crime last year.

“At one period, armed robberies by footpads were nightly occurrences, committed for the most part by Cantonese gangsters armed with knives and pistols. In many cases, the pistols were dummies, but were, nevertheless, effective for the purpose.”6

During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), gun crimes came to a halt as strict controls over movement of persons and swift, harsh punishments on criminals were carried out by the Japanese Military Administration. This lull lasted only as long as the Occupation years though.7

Secret society members in Singapore were responsible for committing various acts of violence and crime on the island during colonial times. Gang members usually sport tattoos on their bodies, like this snake tattoo, to symbolise their affiliation to a particular gang. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Secret society members in Singapore were responsible for committing various acts of violence and crime on the island during colonial times. Gang members usually sport tattoos on their bodies, like this snake tattoo, to symbolise their affiliation to a particular gang. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Gunmen, Gunmen Everywhere

When the Japanese Occupation ended in August 1945, gang activity resumed with a vengeance. Armed robberies and shootouts between police and criminals rose dramatically because of uncontrolled arms trafficking, and the looting of military property and equipment.8 In the last eight months of 1946 alone, more than $4.5 million worth of property was stolen from army ordnance dumps.9

Between September 1945 and December 1946, not a month went by without yet another newspaper report of a run-in between police and gunmen. In 1946, there were 960 reported incidents of armed robberies. The casualties included innocent bystanders such as an Indian employee of The Straits Times, who was caught in the crossfire between police and armed robbers on Robinson Road. On that same day, another shootout took place at Nankin Street, injuring a Chinese man.10

In its 1948 annual report, the police reported that the state of security was such that “lootings, particularly in the Harbour Board area, produced an almost insoluble problem… armed robberies which were reported, and there were many not reported, were in the neighbourhood of three or four every twenty-four hours”.11 On top of that, the police had to contend with armed leftists and their sympathisers who were not above violence. In 1948, a grenade was thrown at labourers who turned up for work during a strike at the Singapore Harbour Board.12

In that same year, however, the police managed to score a big win. After a year of undercover work, Singapore police officers in cooperation with Dutch authorities raided a gun-smuggling ring on Airabu island in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia). The operation led to the seizure of three-and-a-half tonnes of arms and ammunition, and the crackdown of an international syndicate supplying weapons to different parts of Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East. The seized items included submachine guns, Browning automatic rifles, aircraft machine guns and ammunition. The arrests, which took place in Airabu and Singapore, included three Americans, a Filipino, four Britons, an Irishman, a Eurasian, and a woman believed to be an Australian.13

Police cadets of “B” Company at the Police Training School, 1941. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Police cadets of “B” Company at the Police Training School, 1941. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Curbing Gun Violence

To suppress the alarming spike in gun violence, the police did various things. In 1945, it established the Gangs and Radio Sub-branch, using radio communication to help combat armed gangsters.14 Surprise swoops targeting gangs were carried out almost nightly. In one such exercise in 1946, almost 500 men were involved – comprising 280 uniformed policemen, 70 officers and detectives, and 110 paratroopers.

Policemen underwent special training in smashing up gangs and in unarmed combat, and the police force also worked closely with the military police and its counterparts in Malaya to uncover and break up gangs. In addition, officers and men of the Criminal Investigation Department were ordered to be armed at all times in anticipation of encounters with armed gangsters.15

The police also began offering cash rewards of $200 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of persons in possession of arms. This resulted in one gun being recovered almost every day. One informant was reported to have been paid $4,000 after he led police to a small arsenal of arms.16

In 1946 alone, 260 automatics and revolvers, 22 rifles, six Verey light pistols, two Tommy guns, one Sten gun, one submachine gun, 12,922 rounds of ammunition, 160 hand grenades and 21 detonators were seized. In 1947, one of the biggest seizures took place in Bukit Panjang, where 91 cases containing 1,095 hand grenades, a case containing 38 sticks of gelignite and about 2,000 rounds of small arms ammunition were uncovered. The following year, two Chinese men were caught for the illegal possession of 48,952 rounds of rifle ammunition.17

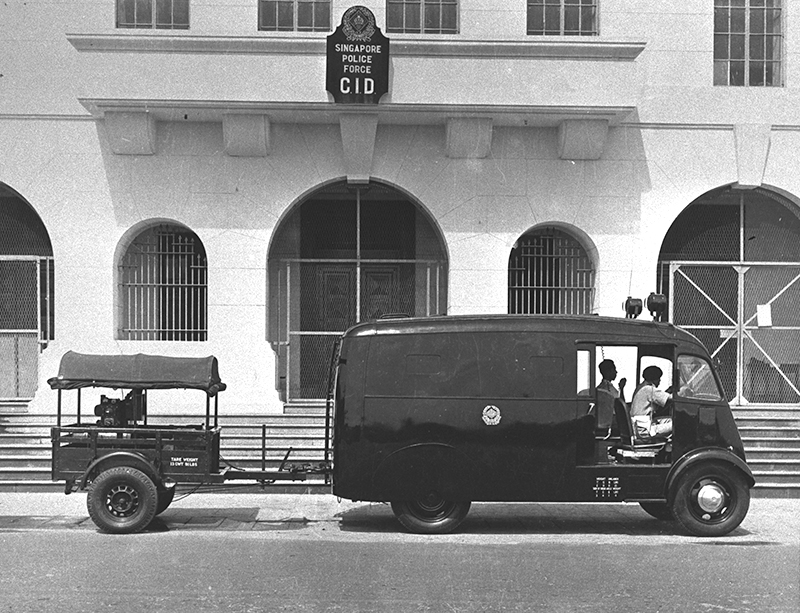

In 1948, the police launched the “999” telephone service that enabled the public to call the Radio Control Room, which was in constant communication with police radio cars. Such cars could be quickly deployed if needed.18

In 1948, the police launched the “999” telephone service that put callers in touch with the Radio Control Room, which was in constant communication with police radio cars. Such radio cars allowed the force to respond more quickly and efficiently on the ground, c. 1950s. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1948, the police launched the “999” telephone service that put callers in touch with the Radio Control Room, which was in constant communication with police radio cars. Such radio cars allowed the force to respond more quickly and efficiently on the ground, c. 1950s. Singapore Police Force Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

These measures, however, did little to stem the tide of an increasing number of crimes involving firearms. In the 1950s and 60s, kidnapping for ransom at gunpoint frequently made the headlines. The victims were mainly wealthy individuals, including millionaire Thio Soen Tioe, kidnapped in 1953; Chung Khiaw Bank vice-chairman Ng Sen Choy in 1957; millionaire Sundram Appavoo Kandiar in 1957; Tan Eng Chuan, grand-nephew of multimillionaire Tan Lark Sye in 1957; “curio king” C.K. Tang of House of Tang in 1960; and Shaw Vee Ming, son of cinema tycoon Shaw Run Run, in 1964. However, not all the victims managed to survive. In 1960, Thye Hong Biscuit chairman Lee Gee Chong was kidnapped and later found murdered.19

Lionel Jerome de Souza, who joined the police force in 1961, recalled his 1965 confrontation with notorious gunman and kidnapper Ah Hiap20 along Victoria Street:

“The next thing I knew was I saw flash light bulbs, ‘poom, poom!’ two shots. I released him. If I were to say I was not shocked, it’s a lie. I was shocked, but somehow or other I managed to get control of myself. I drew my gun, by that time he had rushed across Victoria Street to Cashin Street, towards the old Odeon Theatre. And I fired one round. I don’t think he was hit. I fired a second round. Still he was running inside, then the crowd came out. They were showing the film Von Ryan’s Express. I [shall] never forget. So he got lost in the crowd.”21

In 1957, the police streamlined its alarm system to marshall every available policeman to join in a manhunt within minutes of a kidnapping report.22 Two years later, a special operational unit of detectives was formed to target armed robbers and, in 1964, another “special squad of tough, hand-picked ‘crime busters’” was created for the same purpose.23

More powers were also granted to the police through new ordinances and amendments to existing laws. Starting from 1960, the police could stop and search any motor vehicle suspected of being used in a crime. In 1961, the Kidnapping Act was passed to make the crime punishable by death.24

The kidnapping of millionaires continued well into the late 1960s and 70s though. Robberies involving the use of firearms persisted as well, with 93 reported cases in 1971, 79 in 1972 and 127 in the first half of 1973 alone. There were also payroll heists like the one in 1971 when two gunmen snatched $31,000 meant to pay the week’s wages of some 800 daily-rated employees of International Wood Products Ltd.25

Guns for Hire

The ease of obtaining firearms and the lack of convincing deterrents to using them spurred violent crime. In the early 1970s, it was estimated that there were some 20 gun-hirers in Singapore who rented out weapons believed to have been smuggled in from Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The supply of firearms in Singapore was such that in 1970, The Straits Times reported that “the authorities admit they may never completely disarm the criminals”, but may “succeed in containing the number of guns and blocking ammunition supply lines”.26

Gangster-turned-pastor Neivelle Tan recalled his days gunrunning in the 1950s and 60s. “They [firearms] were almost literally freely sold around town [in Thailand], in the brothels there, even in the hotel rooms. It wouldn’t be a strange thing to go into a gambling den, find somebody losing and taking out his brand-new, or very new-looking automatic pistol and putting it on the table and offering it for sale.”

The guns in Thailand cost about $300 to $400 each, and Tan bought a half dozen of them, which he smuggled into Singapore. “It was really not difficult at all. You could just chuck them in the boot and nobody looks at it. The customs officers hardly looked at it, especially when your boot is empty. You could just put it under the mat or sometimes you just tuck it into your waist. They will search the whole car but not your person.”27

According to Tan, once in Singapore, it wasn’t the firearms that were difficult for gunmen to find, but the ammunition. “The revolvers, the guns were quite easily attainable but the bullets were quite difficult. The main source of the bullets were from the army. I don’t know how it came out, but most of them came out from there.”28

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, the police cracked down relentlessly on gunrunners. In 1972, the infamous Hassan brothers, who were running a gun-smuggling syndicate bringing in arms from Thailand, committed suicide by gun at the cemetery in Jalan Kubor after being surrounded by the police. In 1973, two gun-for-hire syndicates were smashed, and more than 50 pistols and over 1,000 rounds of ammunition were seized.29

The killing of Detective Police Constable Ong Poh Heng in July 1973 – he was shot while intervening in an argument between an armed motorist and a bus driver over who had the right of way30 – appeared to have been the catalyst that led to stiffer penalties imposed for offences committed using firearms.

Police discovery of a cache of abandoned firearms and gear, 1960. David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Police discovery of a cache of abandoned firearms and gear, 1960. David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Eradicating Gun Violence

Ong’s death was repeatedly cited as a reason why parliament should pass the Arms Offences Bill; it was passed and the law came into force in February 1974.31 Under the new law, anyone using or attempting to use firearms with the intent to cause physical injury would face the death penalty. Accomplices of gunmen and arms traffickers could also be punished with death, and long prison sentences awaited those in illegal possession of firearms and ammunition. More importantly, those who consorted or associated with gunmen, or abetted or sheltered them, were also convicted.32

The new legislation had an immediate impact, seeing a dip in the number of armed robberies when the provisions of the bill were announced in August 1973. Between September and November that year, there were just 14 cases, compared with 155 cases from January to August.

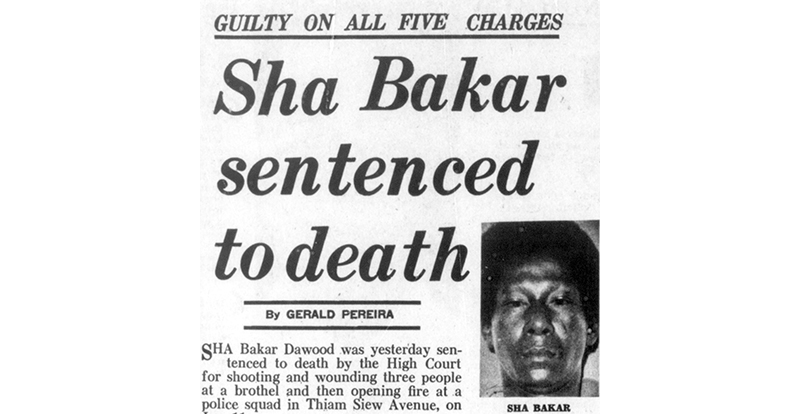

The first gunman sentenced to death under the new act was Sha Bakar Dawood in September 1975. He had shot and wounded three people at a brothel and opened fire on a police squad along Thiam Siew Avenue. Just a month later, the first man sentenced to death for being an accomplice to two armed gang robberies was hawker Talib bin Haji Hamzah.33 The latter case demonstrated that even accomplices to armed robberies would face the full force of the law.

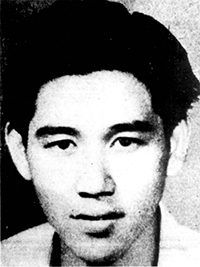

The first gunman sentenced to death under the Arms Offences Act was Sha Bakar Dawood in September 1975. He had shot and wounded three people at a brothel and opened fire on a police squad along Thiam Siew Avenue. The Straits Times, 3 September 1975, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The first gunman sentenced to death under the Arms Offences Act was Sha Bakar Dawood in September 1975. He had shot and wounded three people at a brothel and opened fire on a police squad along Thiam Siew Avenue. The Straits Times, 3 September 1975, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Other factors also contributed to the decline in gun violence. First, more resources were invested in modernising the police force, such as the introduction of new policing methods, improvements to weaponry and the deployment of gun-sniffing dogs at points of entry into Singapore.34

At the same time, there was greater collaboration among ASEAN countries to stem arms trafficking. During the ASEANPOL Conference held in Jakarta in 1983, ASEAN police chiefs pushed for the adoption of several measures, including enhanced penalties for those caught having firearms and the updating of laws to tighten licensing and control of firearms. Concerted efforts were also put in place to enforce gun laws, particularly at entry and exit points, border areas and coastlines. There was also greater exchange of information among the police forces of the different ASEAN countries.35

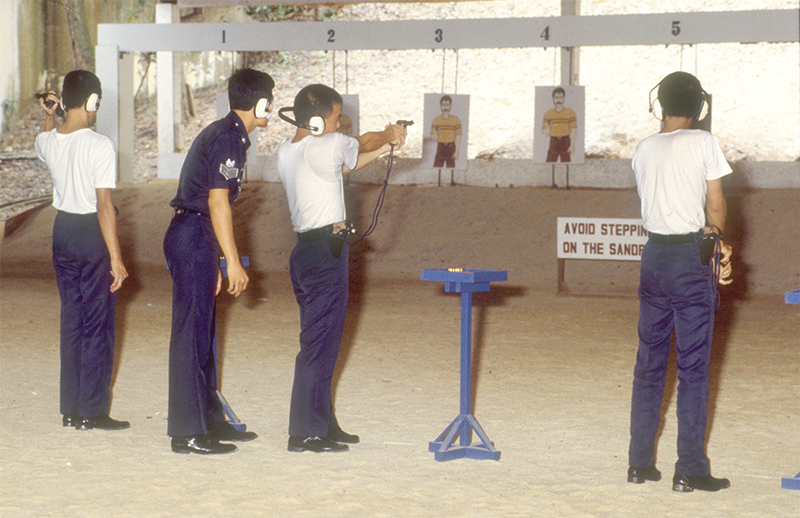

Police officers undergoing training at the Police Training School, 1990. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Police officers undergoing training at the Police Training School, 1990. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In the 1980s, community policing was introduced in Singapore which was geared at partnering the public in keeping the country crime-free. The people’s participation in neighbourhood policing schemes also led to a higher level of public confidence in the police, and the number of arrests due to information and assistance from the public increased from 592 in 1985 to 2,476 in 1986.36

Gun-smuggling rings, however, remained a problem throughout the 1980s. It was through a combination of harsh penalties for possession and use of firearms, increased surveillance of Singapore’s coastlines and points of entry, and greater regional efforts to curb arms trafficking that eventually put an end to gunrunning.

Although gun violence was effectively contained in Singapore during the 1980s and 90s, violent crimes involving the use of firearms would sporadically occur, including a series of goldsmith robberies by gunmen in 1989.37 However, the era of street shootouts and gun battles was effectively over. By the new millennium, gun crime had become a rarity in the city-state.

| FROM SPECIAL SQUADS TO SHOOTING STYLES |

|

| Wanted man Lim Ban Lim was one of the first gunmen to be slain by the new FBI shooting technique adopted by the Singapore Police Force. The Sunday Times, 26 November 1972, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| To deal with armed gangs and secret societies, the police formed special units such as the Phantom Squad created in early 1959. |

| Comprising 10 specially chosen detectives armed with .38 revolvers, the squad would venture into gang territory. The Straits Times reported that the squad’s first confrontation with a gang unfolded the night after its formation. Three members of the squad dressed in dark clothes began patrolling a particularly “bad area”. Before long, they found themselves surrounded by an armed mob. “The gang leader shouted: ‘What game do you play?’ – the usual gangland challenge to strangers to identify their secret society affiliations… The trio knew they had got what they sought. ‘We’re the police!’ they yelled back. War cries rang out and the thugs attacked them. The gangsters were soon put to flight. Three arrests were made and weapons, including a sword favoured by Chinese mediums for their tongue slashing acts, were recovered.”38 |

| In the first six months of operations, the Phantom Squad shot several thugs and arrested more than a hundred. Such was the squad’s reputation that in September 1959, the police seized three homemade guns from a secret society arsenal in Lorong 17 Geylang. The firearms were believed to have been part of the secret society’s preparations for facing the Phantom Squad.39 |

| The squad, however, disbanded following the killing of a suspected gang member under controversial circumstances: a 23-year-old Indian dockyard worker had been fatally shot in the chest during a clash between an armed gang and the police on 3 August 1959. Another unit known as the “Special Squad” – comprising 73 officers and men, including the 10 detectives from the Phantom Squad – was subsequently formed to carry out the same duties.40 |

| The police force also began training its officers to be more effective in facing armed criminals. In November 1971, a new style of shooting used by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was introduced for its “greater speed and applicability”. Prior to this, Singaporean policemen were trained in the British “battle crouch” shooting style. Training consisted of firing at still targets and from behind cover in a crouched position so as to present a small target for the enemy.41 |

| The new technique, however, involved being trained to fire from the hip at fast-moving targets. The heavy Webley and Scott revolver was also replaced with the lighter and smaller Smith and Wesson, which provided a firmer grip and allowed for a faster draw.42 |

| One of the first gunmen to be slain by this new shooting technique was Lim Ban Lim, who had topped the wanted list for 10 years. Lim was gunned down in Queenstown in November 1972. His accomplice, Chow Ah Kow, was shot dead in Clemenceau Avenue 23 days later.43 |

| The FBI shooting method was so effective that by 1975, it was announced that all regular members of the police force would switch to the new style within two years.44 |

Tan Chui Hua is a researcher and writer who has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications. She is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Tan Chui Hua is a researcher and writer who has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications. She is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Khoo, P. (1968, November 12). As the lights went out, Loh fired his machine-gun. The Straits Times, p. 11; A gun battle that began at dawn. (1968, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Criminal. (1925, December 31). The Malaya Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Merely a warning. (1924, November 4). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 31 Dec 1925, p. 6. ↩

-

The Singapore gunman. (1928, August 22). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits-born youths join city crime gangs. (1939, January 18). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The low crime rate in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation is referred to in various oral history interviews and accounts of survivors. For instance, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew wrote in his autobiography, The Singapore Story, that “the Japanese Military Administration governed by spreading fear… punishment was so severe that crime was very rare”. See Lee, K.Y. (1998). The Singapore story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (p. 74). Singapore: Simon & Schuster. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 LEE) ↩

-

University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies. Library. (1945–1954). PPMS 31/File 36, 1945-1954: Singapore Central Intelligence Department, Monthly Crime Reports. Accessible from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: NAB 1490) ↩

-

8 months’ looting cost $4½ million. (1947, April 17). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

1946 was worst year for crime: S’pore had 960 hold-ups. (1947, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 3; Gun battle fought in S’pore city. (1946, June 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Police Force. (1949). Annual report 1948 (p. 2). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.59570074 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore Police Force, 1949, p. 19. ↩

-

Singapore gun runners caught. (1948, September 18). The Straits Times, p. 1; Dutch probe on Airabu isle arms seizure ending. (1948, October 27). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2; Arms worth $340,000. (1948, December 21). The Malaya Tribune, p. 8; Arms ring aimed at huge profits. (1948, September 24). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yong, W.W.E., & Syam Roslan. (2020, February 19). Police nerve centre. Retrieved from Singapore Police Force website. ↩

-

Smashing gangsterdom in Singapore. (1946, April 7). Sunday Tribune (Singapore), p. 3; C.I.D. men armed day & night to shoot it out with city gunmen. (1946, June 23). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Police recover 40 guns in big drive. (1946, July 15). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 12 Jan 1947, p. 3; 1,095 grenades seized by police. (1947, May 9). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore Police Force, 1949, p. 18. ↩

-

999 sends police to your aid. (1948, July 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New doubt in kidnap case. (1953, August 6). The Straits Times, p. 1; Sit, Y.F. (1957, August 30). Kidnap-rescue drama . The Straits Times, p. 1; $5,000 reward for news of abducted man . (1957, October 16). The Straits Times, p. 9; Box was his ‘cell’ for 13 days. (1957, September 24). The Straits Times, p. 1; Millionaire’s nephew is kidnapped. (1957, November 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; Sam, J. (1960, July 17). C.K. Tang kidnapped. The Straits Times, p. 1; Murder of the ‘biscuit king’: A vengeance killing, says father. (1960, April 25). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; Sam, J., & Cheong, Y.S. (1964, February 6). Cinema magnate Shaw’s son is kidnapped. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ah Hiap was a member of the dreaded kidnapping ring operated by Loh Ngut Fong, who later died in a dramatic shootout with police in 1968. ↩

-

Gupta, S. (Interviewer). (2015, January 6). Oral history interview with Lionel Jerome de Souza. [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003961/10/7, p. 236] Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Rutherfurd, N. (1957, November 24). Plan to beat kidnappers. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Top sleuths to stop robberies. (1959, December 22). The Straits Times, p. 11; Special ‘crime busters’ squad to fight pay grabs. (1964, February 3). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Police Force. (1961). Annual report 1960 and 1961 (pp. 4–5). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.59570074 SIN); Singapore Statutes Online. (2020, June 4). Kidnapping act. Retrieved from Singapore Statutes Online website . ↩

-

Death for the trigger happy gunmen now. (1973, December 1). The Straits Times, p. 7; Kutty, N.G. (1971, December 17). $31,000 payroll grab. (1971, December 17). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Basapa, L. (1970, May 18). Fighting the illegal gun trade. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1995, June 15). Oral history interview with Neivelle Tan (Reverend) [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001600/47/33, p. 393]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1995, June 15). Oral history interview with Neivelle Tan (Reverend) [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001600/47/34, p. 236.] Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Kutty, N.G. (1972, December 18). Betrayal led to death for Hassan brothers. The Straits Times, p. 1; More robbers take to use of guns. (1973, December 14). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wee, B.H. (1973, July 14). Anger grips the police. New Nation, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 1 Dec 1973, p. 7; ‘Death for gunmen’ law in force. (1974, February 11). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Statutes Online. (2020, June 4). Arms Offences Act. Retrieved from the Singapore Statutes Online website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 1 Dec 1973, p. 7; Pereira, G. (1975, September 3). Sha Bakar sentenced to death. The Straits Times, p. 8; Accomplice in armed gang holdup sentenced to death. (1975, October 2). The Straits Times, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fong, K.K. (1984, February 13). The gun-sniffing police dogs. Singapore Monitor, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wee, P. (1984, March 3). Are more criminals toting guns? The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Police’s 3 pillars of strength. (1987, March 24). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Police seek help in hunt for goldsmith robbers. (1989, April 13). The Straits Times, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ee, B.L. (1959, March 15). Police phantom force in search of trouble. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wee, B.H. (1973, April 4). A date with danger…. New Nation, p. 9; Home-made guns seized. (1959, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Label these ‘phantoms’ says the coroner at inquest on shot man. (1959, October 30). The Straits Times, p. 2.; New Nation, 4 Apr 1973, p. 9; Highly commended. (1959, October 4). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Basapa, L. (1971, November 21). ‘Shoot faster’ plan for police force. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Shooting from the hip FBI style…. (1971, November 19). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kutty, N.G. (1973, January 21). Fewer crimes but more murders: FBI-style shooting helps the cops get their men. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Shooting FBI-way for all PCs. (1975, August 19). New Nation, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩