Looking Back at Queenstown Library’s 50 Years

Paddy Jonathan Ong traces the history and development of Singapore’s first branch library since it opened its doors in 1970.

Queenstown Branch Library on the night of its official opening, 30 April 1970. The ceremony

began at 8.15 pm. Crowds are seen waiting to enter the library. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Queenstown Branch Library on the night of its official opening, 30 April 1970. The ceremony

began at 8.15 pm. Crowds are seen waiting to enter the library. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Fringed by tall palms and old rain trees, a modest, two-storey building nestles in the quiet street that is Margaret Drive. With its characteristic bowtie arches and floor-to-ceiling glass windows, the Queenstown Public Library has been a neighbourhood landmark for half a century. Although not a grand edifice, this humble building has played a significant role in the social and cultural life of a young nation.

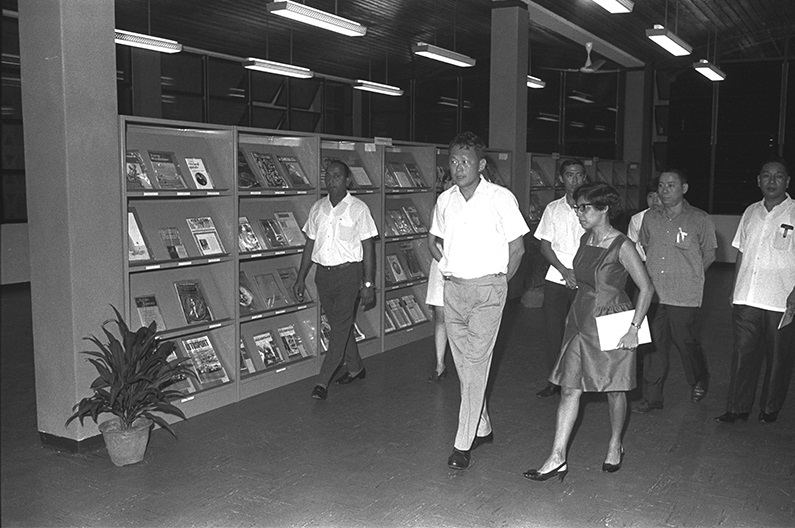

Queenstown is Singapore’s first satellite town, and the prototype for the country’s housing and urban development.1 Named after Queen Elizabeth II in commemoration of her coronation in 1953,2 the housing estate was built by the Housing & Development Board in the early 1960s.3 On 30 April 1970, Queenstown Branch Library, Singapore’s first branch library, was officially opened by founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew is taken on a tour of Queenstown Branch Library by Mrs Hedwig Anuar, Director of the National Library, during its official opening on 30 April 1970. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew is taken on a tour of Queenstown Branch Library by Mrs Hedwig Anuar, Director of the National Library, during its official opening on 30 April 1970. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The opening of the library was significant because it marked the move towards making books accessible to all Singaporeans, at a time when few could afford them. Until 1960, the Raffles Library, located within the Raffles Museum (what is now the National Museum of Singapore), was Singapore’s only subscription-based library for the public with its predominantly English collection available to fee-paying members.4 (There were also part-time branch libraries located on Lim Ah Pin Road and in Siglap but these had small collections and were only opened on certain afternoons a week.5)

When the Raffles National Library opened in a new building next to the Raffles Museum on 12 November 1960, membership was made free for Singapore residents. Located on 91 Stamford Road, Raffles National Library was renamed the National Library in December 1960.6

The Need for More Libraries

In the 1960s, public library services in Singapore consisted of the National Library on Stamford Road, small part-time branch libraries in Siglap and Joo Chiat, mobile library services7 and the part-loan service, which was essentially a bulk loan service to organisations and institutions such as prisons and hospitals. Early on, the National Library’s management recognised that there was a need to decentralise library services further to allow more people to use the library. This meant opening new branches across the island.8

In 1963, the National Library’s first annual report identified a number of suitable locations for the branch library: Queenstown, which was near the city; Jurong in the west; and Katong or Geylang in the east. Jurong was only lightly inhabited at the time, and Katong and Geylang were still served by the Joo Chiat and Siglap part-time branch libraries, so Queenstown was eventually chosen. Minister of State for Culture Lee Khoon Choy made the announcement in parliament in 1966.9

In a memo dated 20 April 1967 to the Ministry of Culture, Prime Minister Lee threw his weight behind the expansion of libraries, saying “it is a development to be welcomed and encouraged, and the facilities must be expanded to take in our ever growing educated youths”.

Once funding was approved, the librarians began drawing up a plan for the building, working closely with government architects from the Public Works Department. Chan Thye Seng, who was then Head of the Library Extension Service, was appointed the Head Planner for the library. In an interview with the Oral History Centre, he recalled: “Kenneth Rosario was the lead architect. He was a very friendly architect and easily accessible. His office was in Kallang and any time, I could go to see him, go over details with him and make amendments and so on. It was a very happy working relationship.”10

The new library’s design was austere and modernist, and took into consideration the climate and the technology at the time. Each floor was designed to have high ceilings to provide good air circulation as there was no air-conditioning. Floor-to-ceiling windows helped with ambient lighting and ventilation, while the glass windows were tinted to counteract the bright sunlight. These windows also enabled those passing by to look in. The library was built to accommodate 200,000 books and had a seating capacity for 280. The Children’s Room was on the first floor, while the Adult & Young People’s Room and Reference Section were on the second floor.11

Books were acquired from the United Kingdom, Malaysia, India, Taiwan and Hong Kong, while the library furniture had to be custom built and procured through the central supply arm of the government. Recalled Chan: “We had to draw the diagrams out for adult and children’s reading tables to differentiate them; the sloped and flat trolleys, and catalogue cabinet stands. It was not uncommon for existing staff to measure dimensions of various furniture and draw them out on paper with the measurements, to send an order to the manufacturers.”12

Construction of the library took about a year. After it was completed in December 1969, the installation of furniture and equipment, and the shelving of books took about three months. Library staff personally delivered the books to the library, using the fleet of mobile library vehicles for transportation. The opening ceremony was a grand affair with a “dragon dance and all the grassroots leaders,” recalled Chan. “[A stage was built] outside the library so [Prime Minister Lee] could give an address and the grassroots leaders lined up to shake his hand.”13

Superlatives and Success

At the opening, Prime Minister Lee described Queenstown Branch Library as “a milestone in our rising standards of life” and announced that similar libraries would be set up in every major housing estate such as Toa Payoh, Katong, Jurong and Woodlands. He noted that these libraries would provide convenient access to books which most people could not afford to buy, and they would also be “sanctuaries of peace and quiet where concentration and better work is possible”. Queenstown Branch Library, he said, marked “one milestone along the road up the hill towards a more educated society”.14

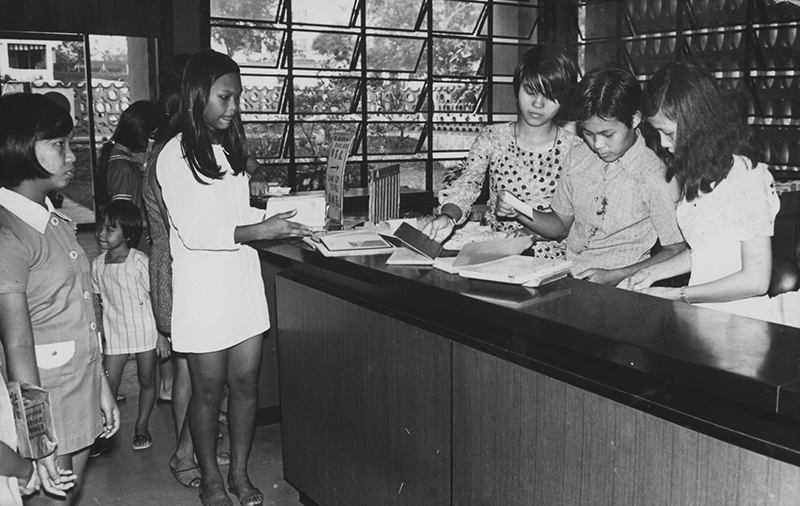

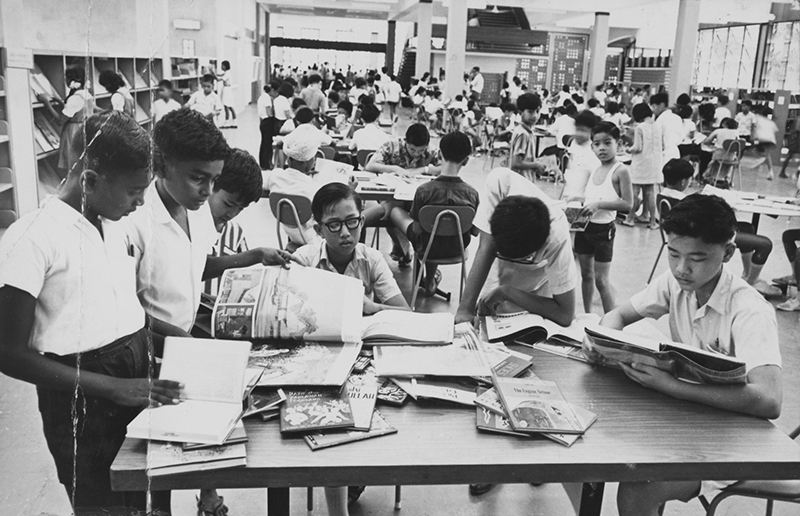

The library’s popularity was evident in the snaking queues at the counter that formed on Saturdays as people borrowed and returned books. Additional staff had to be deployed to handle the crowd, many of them students in their early teens or younger. The library was so popular that by the end of 1972, it had achieved 97 percent of its membership target of 24,000. The number of books borrowed that year also saw a 15.9 percent increase to 1.76 million, compared with 1.5 million loans in 1971.15

Patrons queuing up for library services at Queenstown Branch Library, 1970s. The counter is manned by three teenagers. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Patrons queuing up for library services at Queenstown Branch Library, 1970s. The counter is manned by three teenagers. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Among those young bookworms was former Member of Parliament Chan Soo Sen. Chan remembered how he had been impressed when he visited the library for the first time as he had never seen so many books before. He said: “It was a nice environment. Near my place. Just walked five minutes from there.”16

Another regular visitor to the library was Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen, who grew up around Tanglin Halt and Commonwealth Drive. He recalled: “… as a teen you sort of go and walk, what would be considered quite far, 20 minutes, 30 minutes, and go out and go to your library… The library was very useful because we would spend afternoons just reading.”17

Senior Minister of State Heng Chee How, who grew up in Queenstown in the 1970s, was a regular user too. “I wouldn’t claim that I was particularly studious or anything like that,” he said. “But that place I like it a lot because I do like to read and couldn’t afford buying books anyway [at] that time. When I want to research, that’s the only place where you have encyclopaedias, only hoping that when you get to the page, that it’s still there; it’s not been torn out.” The Queenstown library still holds fond memories for him. “When you close your eyes, you can still remember how the shelves made certain sounds,” he recalled.18

The new branch library also received praise from academics and overseas visitors. In 1971, Jay E. Daily, Professor of Library Science at the University of Pittsburgh, was in Singapore to gather research for a book on comparative librarianship. Having examined the library systems of 45 countries, he said: “Los Angeles has a very good public library system, among the best in the United States, but I think that your Queenstown Branch Library is better than the branch libraries in Los Angeles. One expects something massive and monumental for national libraries, but branch libraries are usually neglected. I have seen nothing in the East to compare with Queenstown.”19

But the most important validation came from regular Singaporeans. Iris Lim, a former resident of Queenstown who lived near the library recalled: “When I was in primary school, every day I would go to the library.” As a child, she would devour the fairytales and folktales of various cultures, all translated into Mandarin, and she said she eventually read the entire collection. “That’s why my Chinese is so good,” she quipped.20

Hedwig Anuar, then Director of the National Library, was particularly pleased with the library’s success in attracting non-English educated patrons. “Some make use of the library as a club. They come regularly to read, meet their friends and attend the various activities. They even know the librarians by name and the librarians too know their names,” she said.21

The packed reading room of Queenstown Branch Library, 1970s. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The packed reading room of Queenstown Branch Library, 1970s. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

More Than Just Books

Beyond being a repository of books and knowledge, libraries also became community spaces. As one of the few spaces accessible to the public in the 1970s, the library organised a plethora of programmes and events, some of which were quite unorthodox for a space meant as a peaceful sanctuary. There were gardening or bonsai talks; arts and crafts sessions for children; talks and presentations on photography, bridal makeup, car design; and even a forum on whether television would replace books.22

Then there were events like a karate demonstration in 1972 by the Singapore Karate Association, where an instructor and seven black belts demonstrated free-sparring movements and smashed bricks with their fists and legs before 200 wide-eyed children. The next year, the library hosted the band of the 1st Battalion Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, as they performed hits by Elvis and a Mozart concerto to a large crowd packed against and between the shelves.23

The library also organised programmes that took patrons outside of the space, such as the visit to the camp of the 6th Battalion of the Singapore Infantry Regiment in 1972. This was aimed at helping civilians understand military life.

These events were all planned and facilitated by the librarians themselves in an effort to break down the barriers between librarians and patrons, to cultivate good reading habits as well as provide social and cultural enrichment. The library was becoming a livelier place. As National Library director Anuar noted, “the [stereotypical] image of librarians as shy, mousey and retiring is no longer true. They are now modern, fashionable and able to get along well with children, teenagers and adults”.24

These library events continued through the decades. Kweh Soon Huat, who joined Queenstown Branch Library in 1991 as a librarian, organised talks by professional athletes when Singapore hosted the Southeast Asian Games in 1993. “I invited a few sports personalities like Abbas Saad to the library,” he recalled. “He spoke about his achievements and did some football skills on the stage. The crowd was huge, it was full house.”25

External organisations also used the library’s facilities for their own programmes. In 1986, the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) organised a public forum at the library on the proliferation of sexist advertisements in the media. It subsequently made the news. AWARE also used the library for forums on polygamy and the Women’s Charter, and on equality in marriage and divorce. The last one actually featured Anuar as one of the speakers.26

The library was also an incubator for the arts. Jasmin Samat Simon, one of the founders of local children’s theatre and drama company ACT 3 (now two entities: ACT 3 International and ACT 3 Theatrics), recalled putting on a small Christmas production in the library with members of the Friends of the Library group.27

Modernising the Library

To keep pace with technological advancements, Queenstown Branch Library upgraded its facilities over the years. In 1978, it became the first branch to become fully air-conditioned. Five years later, the library began offering audio-visual services where patrons could listen to music, watch feature films, slides and cartoons, and access newspapers on microfilm in specially equipped rooms.28 In 1984, the library was renovated again, reopening after three months with new facilities such as a lecture hall that had a stage, spotlights and a dressing room, and refurbished children’s and adults’ sections.

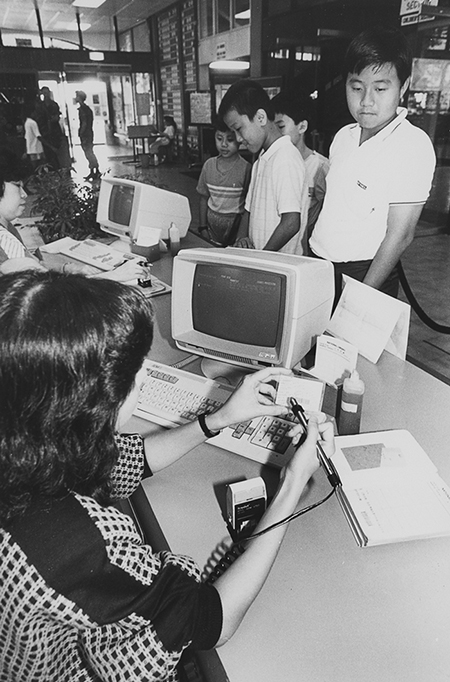

One of the biggest upgrades was not made to the physical infrastructure though. In 1987, Queenstown became the first branch library in the National Library’s network to computerise its loan and membership services, and to have a computerised public access catalogue.29 Books and periodicals were barcoded, and patrons could now borrow these items using just one credit card-size library card with a unique barcode on it (i.e. the library membership number). Using the computerised catalogue system, patrons could also search for books throughout the National Library’s network.30

A patron watches as the library staff scans the barcode on his new library membership card, 1980s. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

A patron watches as the library staff scans the barcode on his new library membership card, 1980s. PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The 1990s saw a big change to the role of libraries in Singapore. In June 1992, the Library 2000 Review Committee headed by Tan Chin Nam, Chairman of the National Computer Board and Managing Director of the Economic Development Board, was convened to review the public library system in Singapore. To lead public libraries into the information age, the National Library became a statutory board on 1 September 1995 with Tan as its first chairman and Christopher Chia as the first chief executive.

The newly formed National Library Board (NLB) aimed to “expand continuously the nation’s capacity to learn” and to “educate [the] people to maximum potential throughout life”.31 This marked a new era for library services in Singapore and as part of that, all branch libraries were renamed community libraries. Queenstown Branch Library became known as Queenstown Community Library (all community libraries were later renamed public libraries).

After the NLB was set up, the automation of library services picked up the pace. In 1996, self-borrowing stations and the bookdrop service were introduced in all community libraries, including Queenstown. With multiple automated self-borrowing stations, the process of borrowing books became much faster. The introduction of a bookdrop service allowed people to return library books easily and quickly, even when the library was closed. The snaking queues to borrow and return books seen on weekends became a thing of the past.

In 1998, NLB became the first public library system in the world to use radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology for its Electronic Library Management System to manage the tracking, distribution, circulation and flow of library materials.32 RFID tags were affixed in all books, making NLB one of the largest users of the technology at the time. The bookdrop became automated and allowed returns to be recorded almost immediately. In addition, patrons no longer needed to return items to the library they had borrowed them from. Patrons of Queenstown Library, as well as all the other NLB libraries, benefitted from these improved processes.33

In the following decade, community libraries took turns to undergo upgrading and renovation works in line with the recommendation by the Library 2000 report to create “a stimulating and lively environment” in libraries and to make “a visit to the library an enjoyable and enriching experience”.34

In 2003, Queenstown Library underwent a nine-month renovation to do just that. The auditorium was removed, a lift was installed for elderly patrons and persons with disabilities, and the storytelling room was replaced with a cafe. The staircase was moved from the centre to the corner of the building so that there was more space for exhibitions. The service counter was also relocated nearer the entrance to welcome visitors. “The patrons were very happy with the renovation” said Goh Siew Han, who joined Queenstown Community Library in 1998 and is currently its Head Library Officer.35

New Developments in Queenstown

While the Queenstown Library was undergoing physical changes, the neighbourhood was also due for major redevelopment. In 1994, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) issued a Development Guide Plan for Queenstown that included proposals for a new sub-regional centre in Buona Vista, new infrastructure to link nearby tertiary educational institutions to business parks, and new high-density housing. Many of the older flats in the area were also selected for the Selective Enbloc Redevelopment Scheme, with many blocks making way for rejuvenated housing, both public and private.36

In the following two decades, a number of iconic landmarks and buildings in Queenstown were demolished, such as Tah Chung Emporium and the Queenstown Remand Prison. Goh, the Head Library Officer, recalled: “There was an NTUC and the old cinema. We used to have KFC for lunch at the bowling alley, watching people bowl while we ate. A few banks as well. They were all there until 2011 or 2012. When all the buildings were torn down, there was nothing to eat.”37

In 2013, the URA announced that three buildings in the area – Queenstown Library, the former Commonwealth Avenue Wet Market and Alexandra Hospital – would be gazetted for conservation under its 2014 Master Plan.38 While the library was now safe from the wrecking ball, many old buildings in Queenstown made way for the new Dawson housing estate and other private residential projects. The library became a quieter place, still busy on weekends and averaging hundreds of thousands of loans every year, but a far cry from the snaking queues and packed reading rooms of yesteryear.

An exterior view of Queenstown Public Library, 2020. The bow-tie canopies and lattices on the facade have not changed since the library opened in 1970. Photo by Paddy Jonathan Ong.

An exterior view of Queenstown Public Library, 2020. The bow-tie canopies and lattices on the facade have not changed since the library opened in 1970. Photo by Paddy Jonathan Ong.

In 2014, an underused foot reflexology path behind the library was removed and a garden set up with the help of the National Parks Board’s Community in Bloom project. Edible plants, herbs, spices and fruit trees were planted in the garden, which is managed by volunteers. Today, Queenstown Public Library is the only library with a gardening programme.

The library continues to support the community, which includes students from two nearby schools for the disabled: Rainbow Centre and the Movement for the Intellectually Disabled of Singapore Lee Kong Chian Gardens School (MINDS LGS). Students from Rainbow Centre help to create book displays, while those from MINDS LGS tend to the garden and have reading sessions in the library. Clients served by the Society for the Physically Disabled also visit the library to learn about library services, the history and heritage of the library, and to attend activities such as movie screenings, book talks, and arts and crafts sessions.

A library officer at Queenstown Public Library conducting a storytelling session, 2017. Such programmes are usually very well received by the public. Photo by Paddy Jonathan Ong.

A library officer at Queenstown Public Library conducting a storytelling session, 2017. Such programmes are usually very well received by the public. Photo by Paddy Jonathan Ong.

Initiatives to reinvent the library to keep up with the changing needs of library users are already in place. In 2020, the library will undergo further changes by implementing more digital services and creating social spaces for patrons. There will be more automation of basic services to free up library staff to take on new roles to better serve the information needs of patrons as well as create experiences to grow the library as a community space. Plans are also afoot to rejuvenate the library’s interior.

Although most of the old flats in Margaret Drive have been torn down, with those in nearby Tanglin Halt and Commonwealth Drive on the demolition list, upcoming housing developments in the area will, undoubtedly, bring new patrons to the library. Von Tjong, an educator and artist-designer in her 40s, is waiting to move into her new flat in Dawson, but has already begun volunteering with the library. She is presently conducting free art jamming sessions for adults and is looking forward to living just across the road from Queenstown Library because it “provides us with simple pleasures; doing some gardening or just having some quiet time and a sense of peace”.39

Paddy Jonathan Ong has been an Associate Librarian with Queenstown Public Library since 2017. He manages its community garden and the adults’ collection, and also creates services and programmes to help adults rediscover their love for reading and learning.

Paddy Jonathan Ong has been an Associate Librarian with Queenstown Public Library since 2017. He manages its community garden and the adults’ collection, and also creates services and programmes to help adults rediscover their love for reading and learning.

NOTES

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (1994). Queenstown planning area: Planning report 1994 (pp. 4, 8). Singapore: The Authority. (Call no.: RSING 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

What’s in a name? (2005, August 9). The Straits Times, p. 114. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; National Library Board. (2014, April 8). Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation celebrations in Singapore. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Asad Latif. (2009). Lim Kim San: A builder of Singapore (pp. 60–61). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 363.585092 ASA) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2020, April 30). History of National Library Singapore. Retrieved from National Library Board website; Seet, K.K. (1983). A place for the people (p. 18). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 027.55957 SEE); Lim, P.H. (2010, August). The history of an emerging multilingual public library system and the role of mobile libraries in post colonial Singapore, 1956–1991. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 15 (2), 85–108. Retrieved from University of Malaya website. ↩

-

Upper Serangoon folk will soon have their own library. (1951, October 6). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. (1960). 1960 Supplement to the laws of Singapore (p. 1). Raffles National Library (Change of Name) Ordinance 1960 (Ord. 66 of 1960). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 348.5957 SIN); Cultural awakening. (1960, November 13). The Straits Times, p. 5; Out goes the name Raffles. (1960, November 21). The Straits Times, p. 9; Raffles’ name will live on: Rajaratnam. (1960, December 1). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (1999). Mobile Library Services (1960–1991) written by Wong Heng & Thulaja Naidu. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2000, May 10). Oral history interview with Chan Thye Seng [Transcript of MP3 recording no.: 002265/15/9, pp. 96–102]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Library (Singapore). (1963–1965). Annual report 1963. Singapore: The Library. (Call no.: RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); N-Library: The first branch at Queenstown. (1966, December 21). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chan Thye Seng, 10 May 2000. ↩

-

My Community. (2017). Queenstown Public Library 10. Retrieved from My Community website; Chan, T.S. (1971). A branch library for the people. Singapore Libraries, 1, 63–66. (Call no.: RCLOS q020.5 SL); National Library Board. (2000). Queenstown Community Library written by Wong Heng. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chan Thye Seng, 10 May 2000. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chan Thye Seng, 10 May 2000. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1970, April 30). Address by the Prime Minister at the opening of the Queenstown Branch Library on Thursday,30th April 1970 (pp. 2–3) [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The queue up in Queenstown. (1978, April 3). New Nation, p. 5; More are taking to reading, says library. (1973, January 24). New Nation, p. 3; A record rise in library members. (1973, January 24). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2007, April 17). Oral history interview with Chan Soo Sen [Transcript of MP3 recording no.: 003151/01/01, p. 9]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2007, April 4). Oral history interview with Dr Ng Eng Hen [Transcript of MP3 recording no.: 003143/01/01, pp. 8–15]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2007, Apr 3). Oral history interview with Heng Chee How [Transcript of MP3 recording no.: 003142/01/01, p. 6]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

High praise for library. (1971, March 13). New Nation, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kiang-Koh, L.L. (Interviewer). (2016, October 13). Oral history interview with Iris Lim Ai Keng [MP3 recording no.: 004089/04/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ismail Kassim. (1974, May 21). Making libraries social and cultural centres. New Nation, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

TV replace reading? (1972, April 28). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Karate thrills for 200 kids. (1972, October 30). The Straits Times, p. 7; Schoon, J. (1973, October 15). A sound of music at the library. New Nation, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Nation, 21 May 1974, p. 4. ↩

-

Personal interview with Kweh Soon Huat, 1 June 2020. ↩

-

Forum on sexist ads. (1986, November 3). The Business Times, p. 3; Forum on polygamy. (1987, January 6). The Business Times, p. 2; Forum on marriage draws up new ‘contract’. (1986, December 6). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kiang-Koh, L.L. (Interviewer). (2018, January 17). Oral history interview with Jasmin Samat Simon [MP3 recording no.: 004239/03/02]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Hedwig, A. (1983, May 13). Library to start audio-video loan scheme. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2000. ↩

-

Lim, R. (1987, October 24). Queenstown Library goes on-line. The Straits Times, p. 17; Rohaniah Saini. (1988, May 20). On-line system boon to library users. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, C.N. (1994). Library 2000: Investing in a learning nation: Report of the Library 2000 Review Committee (pp. 9, 22, 74, 102). Singapore: Ministry of Information and the Arts. (Call no.: RSING 027.05957 SIN) ↩

-

National Library Board. (1999). Annual report FY1998. Retrieved from National Library Board website; National Library Board. (2018). World class libraries and archives for a knowledgeable nation (pp. 22, 105–106). Singapore: National Library Board. [Note: RFID is an electronic system for automatically identifying items. It uses RFID tags, or transponders, which are contained in smart labels consisting of a silicon chip and coiled antenna. The Electronic Library Management System is an integrated system comprising self-check machines, automated bookdrops and sorting machines. ↩

-

Ramchand, A., Devadoss, P.R, & Pan, S.L (2005). The impact of ubiquitous computing technologies on business process change and management: The case of Singapore’s National Library Board (pp. 139–152). In C. Sørenson, Y. Yoo, K., Lyytinen & J.I. DeGross. (Eds.), Designing ubiquitous information evironments: Socio-technical issues and challenges. IFIP – The International Federation for Information Processing Digital Library, 185. Boston, M.A.: Springer. Retrieved from Springer website. ↩

-

Personal interview with Goh Siew Han, 1 June 2020. ↩

-

Kwek, L.Y., & Lee, J. (2015). My Queenstown heritage trail (p. 7). Singapore: My Community. (Call no.: RSING 915.95704 KWE); Urban Redevelopment Authority, Singapore, 1994, p. 14; Tan, H.Y. (1996, May 1). Queenstown flats selected for en-bloc redevelopment. The Straits Times, p. 1; Hooi, A. (2005, December 30). 3 Queenstown blocks to be redeveloped. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Personal interview with Goh Siew Han, 1 June 2020. ↩

-

Saifulbahri Ismail. (2013, October 3). Three buildings in Queenstown to be conserved. Today, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Personal interview with Von Tjong, 20 June 2020. ↩