The “Tiger” in Singapore: Georges Clemenceau’s Visit in 1920

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the former French premier’s visit to Singapore. Lim Tin Seng has the details.

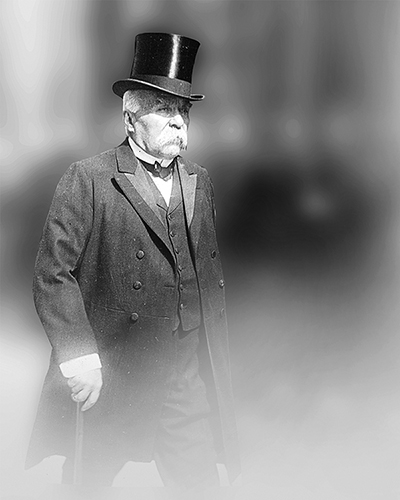

Georges Clemenceau when he was prime minister of France, 1917. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Georges Clemenceau when he was prime minister of France, 1917. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

When the mail steamer Cordillere pulled into Singapore on 17 October 1920, it carried more than the usual assortment of letters, postcards and parcels. Also on board was a distinguished passenger: the former prime minister of France, Georges Eugène Benjamin Clemenceau (1841–1929).1

Nicknamed Le Tigre (The Tiger), Clemenceau was in Singapore from 17 to 22 October en route to Java before returning to the island on 15 November for a one-day stay. The two stopovers took place during his six-month tour of India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), an expedition he embarked upon after retiring from politics.2 It was also the first and only visit to Asia by the man who had led France twice, first from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920, in the final years and immediate post-war period of World War I.3

Arrival of “The Tiger”

On arriving at Johnston’s Pier in Singapore and seeing the huge number of vessels docked off the coast flying a variety of national flags, Clemenceau grabbed the arm of his travelling companion, Nicolas Pietri, and exclaimed: “Et on veut que nous soyons à égalité avec les Anglais!” (“And to think France is on par with the British!”).4

Clemenceau was greeted by a roaring crowd – which he “confessed surprised and touched him” – “carried out in a manner worthy of [a] great visitor”, complete with a guard-of-honour, a red carpet, buntings, marching bands and an overjoyed crowd cheering “Vive Clemenceau!”, or “Long live Clemenceau!”. At the welcome reception, H.A. Low, representing the Municipal Commissioners and the town of Singapore, announced that a new road in Singapore (today’s Clemenceau Avenue) would be named after the Frenchman.5

After leaving Johnston’s Pier, Clemenceau was driven to Government House, where he stayed as the guest of the governor of the Straits Settlements, Laurence Nunns Guillemard.6 Along the way, huge crowds lined both sides of the road cheering him. Among them were 500 children from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (also known as Town Convent) on Victoria Street, which was founded in 1854 by nuns from the Institute of Charitable Schools of the Holy Infant Jesus of St Maur in France. French homes and establishments were also adorned with the French tricolour flag for his visit. Deeply impressed by what he saw, Clemenceau penned the following telegraph message to his relatives later that night:

“Nous sommes arrivés ce matin. Un peu déconcertés par une réception officielle dépassant tout ce qui pouvait être prévu. (…) Singapour est une merveille.”7

[Translation: “We arrived this morning. A little disconcerted by the reception effort beyond anything that could be expected… Singapore is a wonder.”]

“The Tiger” in Singapore

Clemeanceau was almost 80 years old at the time of his visit to Singapore but despite his age, he was remembered for having “an inexhaustible supply of energy”8 and had a packed itinerary during his five-day stay here. His first visit, on 18 October, was to the French Consulate to meet members of the French community. Those present included priests from the Catholic mission as well as French bankers, merchants and engineers. A party of French miners from the Malayan state of Perak also specially made the journey south to meet him.9

Clemenceau’s next stop was Commercial Square (present-day Raffles Place) and High Street for a bit of shopping before proceeding to the Raffles Museum for a tour.

Sometime after 1 pm, Clemenceau boarded the Royal Navy light cruiser H.M.S. Curlew where he inspected the crew, enjoyed lunch with the officers and “astounded everybody with his wonderful energy”. In his speech, Clemenceau stressed the “importance of a close understanding between Britain and France”.10

The next day, Clemenceau visited the General Hospital and the Tanglin Club, and then ended the day with a dinner at the Garden Club organised by the Chinese community and hosted by Dr Lim Boon Keng, a medical doctor and prominent member of the community. Other guests at the dinner included Governor Guillemard and Sultan Ibrahim of Johor.

In response to Lim thanking him for leading the Entente Powers (comprising France, Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan and the United States), Clemenceau said his services had been exaggerated and that the real winners of the war were the soldiers who had sacrificed their lives.11 The former prime minister added that he was enjoying his visit to Singapore and was pleased to find contentment written on the faces of the various people he met. This made him feel like he was back in France. He drew much laughter when he said that it would be great if he could “find a Chinese home” and to be given a place to stay.12

On 20 October, Clemenceau, accompanied by Dr Lim, visited Yeong Cheng Chinese School on Club Street and Singapore Chinese Girls’ School on Hill Street. He was warmly received by the teachers and students of Yeong Cheng School and given a tour by the principal. Before Clemenceau left, he was presented with some artworks made by the students and photos of the school, one of which bore an inscription in Chinese that read “Defender of Peace”.13 After the school visits, Clemenceau paid courtesy calls on prominent Chinese community leaders Eu Tong Sen and Seah Liang Seah at their homes. At the latter’s residence, Clemenceau was shown Seah’s collection of china and other art objects.14

Georges Clemenceau visiting Yeong Cheng Chinese School on 20 October 1920. On his left is Dr Lim Boon Keng. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

Georges Clemenceau visiting Yeong Cheng Chinese School on 20 October 1920. On his left is Dr Lim Boon Keng. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

In the afternoon, Clemenceau, a polo enthusiast, watched a match at the Singapore Polo Club on Balestier Road.15 He ended the day with a dinner given by Governor and Lady Guillemard at Government House. The dinner was attended by many of the city’s prominent community figures and government officials, including Lim, the Chief Justice of the Straits Settlements James Murison and Major-General Dudley Ridout, the Commander of Troops of the Straits Settlements.16

The next day was another busy one for Clemenceau. In the morning, he visited the Town Convent where he delivered a speech in French to the children, paying special tribute to the Reverend Mother. He noted:

“Ici je vois qu’on vous aime et que la Révérende Mère a le secret de se faire obéir sans se fâcher, sans faire de gros yeux, sans menacer toujours. La Révérende Mère se fait obéir avec un sourire, elle fait supporter son autorité avec bienveillance, et une inspiration toujours noble et élevée.”17

[Translation: “Here I see that you are well taken care of and that the Reverend Mother has the secret of being obeyed without getting angry, without stern looks, without always threatening. The Reverend Mother is obeyed with a smile, she conveys her authority with benevolence, and an inspiration that is always noble and distinguished.”]

Georges Clemenceau with monks and nuns at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, 21 October 1920. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

Georges Clemenceau with monks and nuns at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, 21 October 1920. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

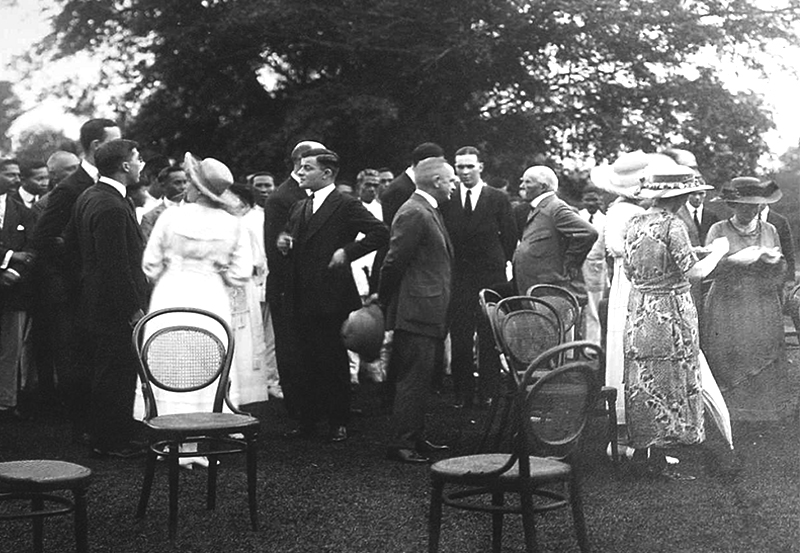

Clemenceau then toured Pasir Ris before returning to Government House for a garden party hosted by Governor and Lady Guillemard.18

A reception given in honour of Georges Clemenceau at Government House. Clemenceau is talking to the man holding his hat. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

A reception given in honour of Georges Clemenceau at Government House. Clemenceau is talking to the man holding his hat. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

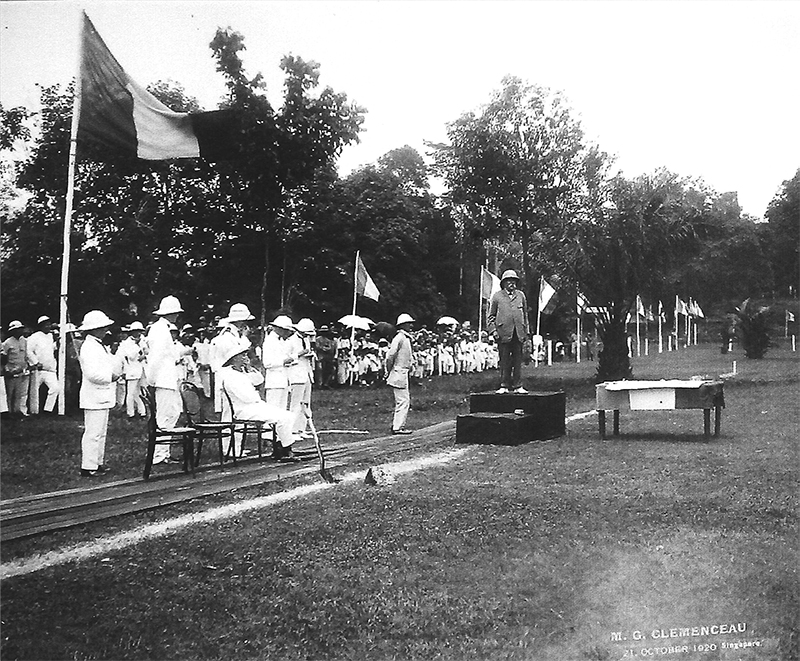

On 22 October, the final day of his trip, Clemenceau attended the groundbreaking ceremony to inaugurate the construction of Clemenceau Avenue. Stretching from Newton Circus to the southern bank of the Singapore River, the new road was conceived as an alternative access between the northwestern part of the city and Orchard Road, which was then served by Cairnhill Road and Cavenagh Road. Clemenceau Avenue would also replace the stretch of Tank Road connecting Orchard Road with Fort Canning Road.19

In his opening speech, Captain E.P. Richards, Deputy Chairman of the Singapore Improvement Trust, highlighted the significance of having a road named after Clemenceau in Singapore as a way to “commemorate lastingly in Singapore the visit of a great man and a great statesman…”20 Clemenceau then turned a shovelful of earth and cut a ribbon to signify the inauguration of the construction of the new road.

In his speech, Clemenceau hailed the road as a symbol of friendship between England and France, and described the day as one of the happiest in his life:

“Do not forget that the name Clemenceau stands for friendship and loyalty between the two countries. In your name and mine, in the name of Great Britain and France, let me express the hope that we remain forever good friends.”21

He then proceeded to plant two palm trees, one on each side of the new road, before the playing of the British and French national anthems brought the ceremony to a close.22

Clemenceau departed from Singapore on the same day on the Dutch vessel Melchior Treub. He toured the Dutch East Indies for about a month before returning to Singapore on 15 November for a one-day visit.23

Georges Clemenceau (on the podium) attending the groundbreaking ceremony for Clemenceau Avenue on 22 October 1920. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

Georges Clemenceau (on the podium) attending the groundbreaking ceremony for Clemenceau Avenue on 22 October 1920. Courtesy of Musée Clemenceau.

| Clemenceau Avenue and Clemenceau Bridge |

| Georges Clemenceau is memorialised in a road and bridge named after him in Singapore. Although the groundbreaking ceremony for Clemenceau Avenue was held on 22 October 1920, work did not commence until 1928 as construction of the road was costly.24 The road was built in two phases. The first section of the road, from the entrance of Government House to Cavenagh Road, was completed in 1929. The second stretch of the road, between Cavenagh Road and Newton Circus, was completed in 1936.25 |

| Clemenceau Avenue was the first road in Singapore to have electric street lamps, installed in the section between Cavenagh Road and Newton Circus.26 These were mercury vapour lamps that generated light using an electric arc passing through vapourised mercury. Prior to this, the streets were lit by gas-filled lamps. |

| Towards the end of the 1930s, a plan to link Clemenceau Avenue to Keppel Road was implemented, resulting in the construction of Clemenceau Bridge across the Singapore River.27 This bridge was built in 1940 but demolished in 1989 to make way for the Central Expressway (CTE). A new Clemenceau Bridge was built in 1991 to connect the CTE’s Chin Swee Tunnel with Clemenceau Avenue.28 |

| Clemenceau Avenue used to host a number of prominent landmarks, including George Lee Motors, the National Theatre, the Rediffusion building and the Van Kleef Aquarium. One historical landmark that still remains is the House of Tan Yeok Nee, a gazetted national monument.29 |

|

| The Van Kleef Aquarium, 1960s. Situated at the foot of Fort Canning Hill at the junction of Clemenceau Avenue and River Valley Road, the aquarium was named after Dutchman Karl Willem Benjamin van Kleef, who lived in Singapore from the late 19th to early 20th century. He bequeathed his estate to the Municipal Commissioners for the beautification of the town. The aquarium was built in 1955 and demolished in 1998. Chiang Ker Chiu Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

The plaque erected by the Municipal Commissioners of Singapore at Clemenceau Bridge. The bridge was completed in 1940 but demolished in 1989 to make way for the Central Expressway (CTE). In 1991, a new Clemenceau Bridge was built to connect the CTE’s Chin Swee Tunnel with Clemenceau Avenue. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The plaque erected by the Municipal Commissioners of Singapore at Clemenceau Bridge. The bridge was completed in 1940 but demolished in 1989 to make way for the Central Expressway (CTE). In 1991, a new Clemenceau Bridge was built to connect the CTE’s Chin Swee Tunnel with Clemenceau Avenue. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Return of “The Tiger”

Despite concerns over his health due to a bronchial illness contracted in Java, Clemenceau witnessed the laying of the foundation stone of the Cenotaph that very evening by Governor Guillemard.30 The war memorial was designed by the architectural firm Swan & Maclaren to commemorate the soldiers who had sacrificed their lives in World War I.31

Unveiling of the Cenotaph by the Prince of Wales during his visit to Singapore, 1922. The Cenotaph is a war memorial for soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. On 15 November 1920, Georges Clemenceau witnessed the laying of its foundation stone. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Unveiling of the Cenotaph by the Prince of Wales during his visit to Singapore, 1922. The Cenotaph is a war memorial for soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. On 15 November 1920, Georges Clemenceau witnessed the laying of its foundation stone. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

That night, Clemenceau had dinner with Governor Guillemard before boarding the Sea Belle to Muar, Johor, to continue with his tour of the region.32 He arrived back in France on March 1921.33

When asked by The Malaya Tribune about what he thought of the island, he replied it was a beautiful place:

“… the trees, the birds, the houses, the happy looks on the faces of the people – all have pleased me immensely. I am especially struck by the way in which the different communities seem to get along without squabbling. Your poor people – they seem so much more contented than the poor people of Europe.”34

And when told that some critics had called Singapore backward, he responded: “Who? Why?… I do not think any such thing! Your colony has a tremendous future before it. It has beauty and talent and it is rich.”35

Some years later, Guillemard wrote in The Times of London about Clemenceau’s visit, calling it one of the highlights in his life:

“… it was my good fortune to meet him in holiday mood… he was like a great boy. He went everywhere, saw everything, and talked to everybody. The charm of his manners was irresistible; his gay humour was infectious; his courtesy won all hearts, and in two days he was the idol of Singapore.”36

| The author would like to thank the Embassy of France for its assistance with photographs and translations. |

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

M. Clemenceau: Singapore gives splendid welcome. (1920, October 18). The Straits Times, p. 9; Last moments of ‘the tiger’. (1929, November 25). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 18 Oct 1920, p. 9; Georges Clemenceau. (1920, October 16). The Straits Times, p. 8; Clemenceau Avenue. (1920, October 23). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An illustrated history, 1819 – today (p. 120). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 305.84105957 PIL) ↩

-

France’s war premier. (1920, October 19). The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Séguéla, M. (2007, July 25). Clemenceau à Singapour [Clemenceau in Singapore] (p. 2). Retrieved from Embassy of France in Singapore website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 18 Oct 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

M. Clemenceau’s visit. (1920, October 15). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Séguéla, 25 Jul 2007, p. 3. ↩

-

M. Clemenceau’s week. (1920, October 21). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

M. Clemenceau. (1920, October 19). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Oct 1920, p. 9; Our distinguished visitor. (1920, October 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Tiger” interviewed. (1920, October 20). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 20 Oct 1920, p. 5. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 Oct 1920, p. 7; The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 Oct 1920, p. 7. ↩

-

Singapore Polo Club. (1920, October 21). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Government House. (1920, October 21). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 Oct 1920, p. 7. ↩

-

Edwards, N., & Keys, P. (1988). Singapore: A guide to buildings, streets, places (p. 247). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 915.957 EDW) ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Oct 1920, p. 9; Clemenceau’s departure. (1920, October 23). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

M. Clemenceau in Java. (1920, October 25). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6; M. Clemenceau’s arrival. (1920, November 15). The Straits Times, p. 8; M. Clemenceau. (1920, November 16). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Clemenceau Avenue. (1928, December 6). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9; Untitled. (1925, May 14). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New traffic route planned. (1929, November 7). The Straits Times, p. 11; Singapore roads. (1929, December 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 11; Municipal commission. (1933, November 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7; Road upkeep in Singapore. (1936, May 7). The Malaya Tribune, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Modern road lighting. (1939, April 1). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Clemenceau Bridge” at Pulau Saigon. (1940, March 1930). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, T.S. (2019, Jan–Mar). Bridging history: Passageways across water. BiblioAsia, 14 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Edwards & Keys, 1988, p. 234; Ramachandra, S. (1969). Singapore landmark (p. 21). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 RAM-[HIS]); National Heritage Board. (2019, November 15). House of Tan Yeok Nee. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Pilon & Weiler, 2011, p. 117. ↩

-

Singapore war memorial. (1920, November 16). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Nov 1920, p. 9. ↩

-

Pilon & Weiler, 2011, p. 120. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 20 Oct 1920, p. 5. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 20 Oct 1920, p. 5. ↩

-

Clemenceau on holiday: The tiger at play. (1929, November 28). The Times. Retrieved from The Times website. ↩