The Extraordinary Life of Kunnuck Mistree

Indian convicts contributed much to the early infrastructural development of Singapore but their voices have rarely been heard. Vandana Aggarwal uncovers the story of one convict who made good.

It is no exaggeration to say that Singapore was built on the backs of Indian convicts. These men – and they were mainly but not exclusively men – laid roads, cleared forests and were involved in the construction of buildings like Sri Mariamman Temple, St Andrew’s Church (now Cathedral), Horsburgh Lighthouse and Government House (today’s Istana). In addition to manual labour, some also worked as hospital attendants, gardeners and domestic servants.

The first batch of 80 Indian convicts arrived in Singapore from Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) in Sumatra on 18 April 1825 on the brig Horatio. Over the decades that followed, more convicts were shipped to Singapore until 1867 when the practice was abolished.1 In history books, these men (and a handful of women) are simply referred to as Indian convicts – faceless and nameless. However, thanks to dogged detective work in the archives, we have been able to piece together the life story of one remarkable individual.

Kunnuck Mistree was 38 years old when he arrived in Singapore in 1825. Once here, he was able to turn his life around: he eventually set up a business, got married and had children. His death, some four decades after stepping on these shores, even merited a mention in the local newspaper. (Different documents use different spellings of his name, including Konnuckram Mittre and Kanak Mittery.2 Kunnuck Mistree, the version chosen for this essay, was how his name was spelt in an official appeal filed by his legal counsel in 1857.3)

From Calcutta to Bencoolen

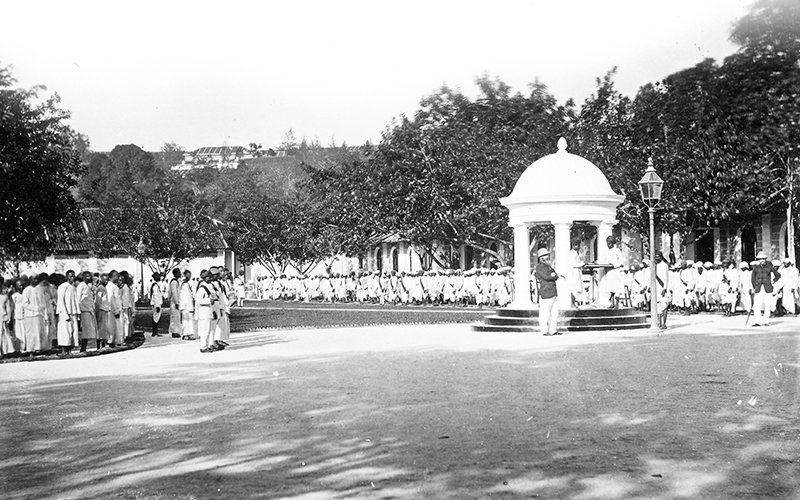

A general monthly muster of convicts at the Bras Basah convict jail, Singapore, 1860–99. The National Archives of the UK, ref. CO 1069/484 (29).

A general monthly muster of convicts at the Bras Basah convict jail, Singapore, 1860–99. The National Archives of the UK, ref. CO 1069/484 (29).

Nothing is known of Mistree’s early life and neither do we have an image of him. What we know of him dates back to 1818 when he was convicted of larceny – a category which includes housebreaking, burglary and dacoity (gang robbery) – in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and was shipped to Bencoolen in Sumatra:

“… in the Christian year one thousand eight hundred and eighteen tried before Sir Francis Workman Macnaghten then Senior Justice of Her Majesty’s Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal on a charge of Larceny and being duly convicted was sentenced to transportation for life to Fort Marlborough Bencoolen in the Island of Sumatra.”4

Mistree was around 31 years old when he arrived in Bencoolen, a convicted criminal sentenced to permanent exile. Despite being relatively young, his future prospects looked bleak.5 Fortunately, Stamford Raffles, who was then Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen, believed that convicts should be given the chance to redeem themselves and, for some, even the chance of emancipation. In a letter to the Court of Directors of the British East India Company (EIC) in 1818, Raffles wrote:

“The object of the punishment as far as it affects the parties must be the reclaiming them from their bad habits, but I must question whether the practice hitherto pursued has been productive of that effect… There are at present about five hundred of these unfortunate people… I would suggest the propriety of the chief authority being vested with a discretionary power of freeing such men as conduct themselves well, from the obligations of service, and permitting them to settle in the place, and resume the privileges of citizenship.”6

Raffles organised the convicts in Bencoolen into three classes: (i) “first class to be allowed to give evidence in court, and permitted to settle on land secured to them and their children; but no one to be admitted to this class until he has been resident in Bencoolen three years”; (ii) “the second class to be employed in ordinary labour”; and (iii) “the third class, or men of abandoned and profligate character, to be kept to the harder kinds of labour, and confined at night”.7

Well-behaved convicts could move up to a higher class and be freed from servitude, while those who failed to toe the line would be demoted to a lower class, and lose their freedom and privileges. For convicts, the promise of a better life made them work towards improving their lot. A similar system was later implemented in Singapore, though with six rather than three classes of convicts.8

Initially, Mistree could have been assigned jobs like clearing forests or building roads like any other convict in Bencoolen, but he eventually managed to get employment as a dresser at the local hospital as a convict of the first class. According to the rules, the earliest this could have happened would have been 1821, three years after his internment.9

The practice of sending Indian convicts to Bencoolen began at the end of the 18th century. In 1787, the EIC sent the first batch of convicts to its settlement in Fort Marlborough. Subsequently, the territories of Penang, Melaka and Singapore also received convict labour.10

Transportation served both penal and economic objectives. Shipping convicts to the colonies gave those territories a source of cheap labour. It also served as a deterrent as transportation was deemed a severe punishment. “To be sent across the ‘kala pani’, or ‘black water’, in a convict ship or ‘jeta junaza’, or ‘living tomb’ as they called it, meant, especially to a man of high caste… the total loss to him of all that was worth living for.”11

In 1797, the EIC passed the first of a number of laws regarding transportation: Regulation IV directed that all sentences of imprisonment for seven years or more would be commuted to transportation in a foreign land. By the end of the 19th century, over 3,000 Indian convicts had been transported to the penal sites of Bencoolen, Amboina (now Ambon Island), the Andaman Islands and Penang.12

Moving to Singapore

Within seven years of his arrival in Bencoolen, Mistree’s life would be up-ended again. This time, though, it would be through no fault of his. The 1824 Anglo-Dutch treaty that demarcated British and Dutch possessions in Southeast Asia resulted in an exchange of territories, with Britain ceding Bencoolen to the Dutch in exchange for Melaka. The Supreme Government in Calcutta decided to relocate all convicts to the Straits Settlements, although convicts of the first class and a few others were given the option of staying back in Bencoolen as free men and women, albeit without the option of returning to India until their term was served.13

Rather than remaining in Bencoolen, Mistree chose to be transported to Singapore. “[C]omfortable and happy in his then position neglected to avail himself of the conditional Pardon accepted by other convicts and was consequently removed to Sincapore [sic].”14

Just before leaving for Singapore, Mistree was given a character certificate that gives us a peek into his life in Bencoolen. Dated 23 March 1825, the name and signature on it are illegible but it confirms that “Connick Mittre” had been employed at the general hospital for seven years and his behaviour during this period was that of “sobriety, honesty, and attention to duties”.15 One month later, on 25 April, Mistree arrived in Singapore on the schooner Anne. For the 38-year-old, the island was to be his third and final home.16

On arrival, Mistree and the other convicts were housed in temporary attap huts in the Temenggong’s village (later called Kampong Bencoolen), located at the mouth of the Singapore River. Not all convicts were automatically given jobs similar to what they did in Bencoolen or enjoyed the same freedom. They were also not placed in the same convict class as before.17

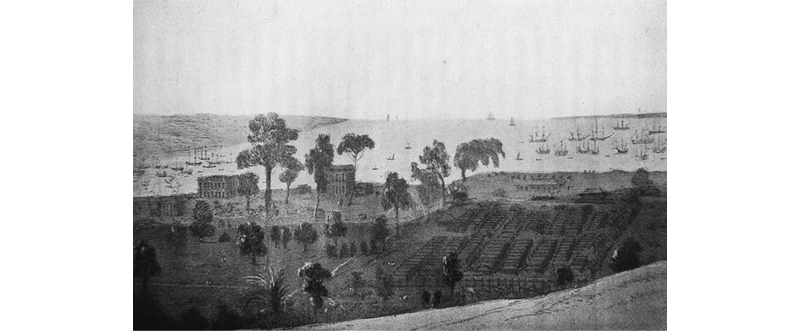

Convicts arriving in Singapore were first placed in an open shed before being housed in these temporary huts near the Bras Basah Canal. A permanent prison, the Bras Basah convict jail, was completed only in 1860. Image reproduced from McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners Their Own Warders: A Record of the Convict prison at Singapore Established 1825, Discontinued 1873, Together with a Cursory History of the Convict Establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797. Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115).

Convicts arriving in Singapore were first placed in an open shed before being housed in these temporary huts near the Bras Basah Canal. A permanent prison, the Bras Basah convict jail, was completed only in 1860. Image reproduced from McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners Their Own Warders: A Record of the Convict prison at Singapore Established 1825, Discontinued 1873, Together with a Cursory History of the Convict Establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797. Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115).

Mistree was assigned the job of a dresser at the Pauper Hospital, possibly due to his prior experience and the connections he had built up in Bencoolen.18 He was likely categorised as a second-class convict, one level down from his convict status in Bencoolen. This may account for the many letters of recommendation he received between 1827 and 1828, when he was nearing the completion of three years of service in Singapore.

This was the mandatory period before a convict could move up to the category of first class, provided all other requirements were met. Various people who knew Mistree in Bencoolen and Singapore wrote letters of commendation. One of these, dated August 1827, was from Dr R. Tytler, Head Surgeon of the Straits Settlements, who certified that “convict Konnuck Ram Mittrie served as a Native Doctor in the General Hospital of Fort Marlboro while I was Head Surgeon Straits Settlement. I always found him very diligent and attentive”.19

In a letter dated 16 June 1827, Dr William Montgomerie, former Acting Surgeon in charge of Singapore, wrote that “Konat Mistery” had always behaved well during his time as a dresser at the Pauper Hospital,20 while Assistant Surgeon Alex Warrand certified on 1 July 1828 that “Kunnick Maistry” had served “in a sober and steady manner” under his charge for a year.21 These letters proved effective and Mistree was upgraded to a convict of the first class.

Convicts were rarely addressed by name in official letters. However, a letter dated 21 February 1828 by Kenneth Murchison, Resident Councillor of Singapore, specifically mentions that “Kunnuck Mittree, dresser Pauper Hospital”, along with two other convicts, had not been given a monthly ration and in lieu, a sum of Rs 2 was added to his salary bringing it up to a princely sum of Rs 12 per month.22

Mistree’s name next appears in 1842 in Lease Deed No. 711, made in favour of “Kunnick Meetre” for a piece of land on Carpenter Street measuring about 324 square feet.23 One might ask how a convict was allowed to own land, but surprisingly this was not unusual as well-behaved convicts were accorded a relative amount of freedom.24 Thanks to the liberal ideas first espoused by Raffles in Bencoolen, convicts could buy land, get married and even own small businesses.

In Singapore, these measures continued and the convicts could move about unshackled.25 Mistree was clearly one of the many convicts who benefitted from this freedom and put it to good use. “The convicts were at this time treated with great indulgence…” and some of the older convicts managed to amass “considerable sums of money, and, indeed, to become possessed of landed property in the town”.26

Mistree did not live a life of penury. He became a financially savvy man who began investing his money in real estate. Carpenter Street lies in the heart of Chinatown and it is unlikely that Mistree resided there. He could have used this property to earn rental income and in all probability still lived in Kampong Bencoolen, where many immigrants from Bencoolen had settled down.27

A Ticket of Leave

In 1845, under the newly formulated guidelines for the management of convicts, Mistree applied for a ticket of leave – a privilege accorded to trustworthy first-class convicts after 16 years of service. Once approved, Mistree would be allowed to live outside convict lines as a respectable member of society and take up a profession of his choice.28

Convict lines were residential quarters specially constructed for convicts. Ironically, convict labour was more often than not used to build them. The convicts in Singapore lived in open prisons in dedicated areas although they could also live in temporary buildings near their place of work. Mistree might have been allotted quarters near the hospital where he worked or, allowed to live as he pleased. All that was expected of him was to stay on the right side of the law and attend muster when required.

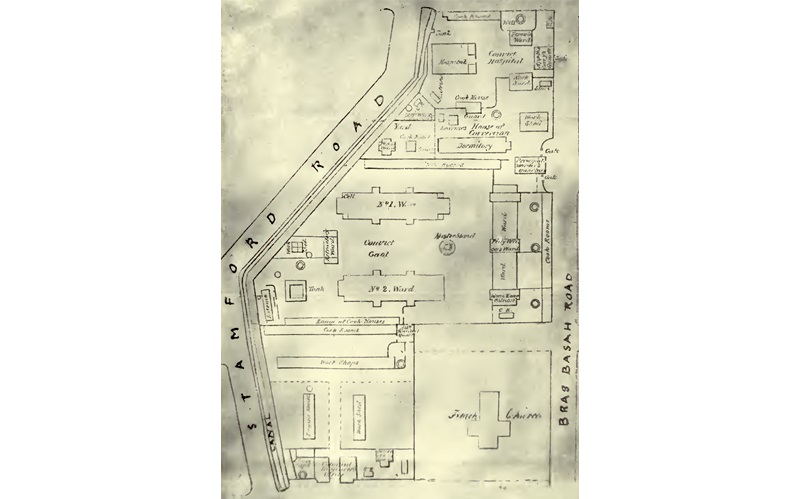

A plan of the Bras Bash convict jail. The jail was built entirely by convict labour and was completed in 1860. The convicts soon realised that “an open campong, or village, had become a closed cage”. Image reproduced from McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners Their Own Warders: A Record of the Convict Prison at Singapore Established 1825, Discontinued 1873, Together with a Cursory History of the Convict Establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797. Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115).

A plan of the Bras Bash convict jail. The jail was built entirely by convict labour and was completed in 1860. The convicts soon realised that “an open campong, or village, had become a closed cage”. Image reproduced from McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners Their Own Warders: A Record of the Convict Prison at Singapore Established 1825, Discontinued 1873, Together with a Cursory History of the Convict Establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797. Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115).

Prisoners in the Bras Bash convict jail, c. 1900. The jail was built by convict labour and was completed in 1860. Photo by G.R. Lambert & Co. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Prisoners in the Bras Bash convict jail, c. 1900. The jail was built by convict labour and was completed in 1860. Photo by G.R. Lambert & Co. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A letter by Senior Surgeon Thomas Oxley on 14 September 1846 certified that “Connak Mistery having a Ticket of leave to provide for himself & being desirous of quitting his situation of Dresser in the Paupers Hospital… leave it now at his own request”.29 A formal certificate bearing the official seal of Resident Councillor Thomas Church validates this information.30

According to John Frederick Adolphus McNair, Executive Engineer and Superintendent of Convicts, convicts who were released from imprisonment with a ticket of leave were “absorbed innoxiously into the native community, and again contributed to the advantage of the place in the various occupations they had recourse to, in order to obtain an honest livelihood”. He added that the convicts “very rarely a second time came under the cognisance of the police, but peaceably merged into the population, and earned their livelihood by honest means”.31

Mistree used his newfound freedom to earn a living as a “native holistic doctor”. By virtue of his long stints at various hospitals in Bencoolen and Singapore, Mistree had gained enough knowledge and skills to practise medicine and, according to his official petition for a pardon, he had “gain[ed] esteem of his countrymen and others… in Sincapore [sic] with whom he [had] come in contact”.32

In 1846, an assistant doctor by the name of J.I. Woodford resigned from government service and opened a dispensary on Church Street in Kampong Bencoolen. Woodford’s name appears both in reference to the property that Mistree bought on Carpenter Street in 1842 and also as the executor of Mistree’s will.33 Woodford was obviously someone whom Mistree had a great deal of trust in and it is possible that Mistree may have been working for Woodford at his dispensary.

Quest for Freedom

In 1855, three decades after Mistree first set foot on Singapore, he began the process of asking to be pardoned and to be allowed to return to India. Apparently, Mistree had written to Whitehall in London, which responded in a reply dated 7 August 1855, advising “Konuck Ram Mittre” to refer the matter to the Governor-General of India as the latter had the authority to grant a remission of sentence if he so desired.34

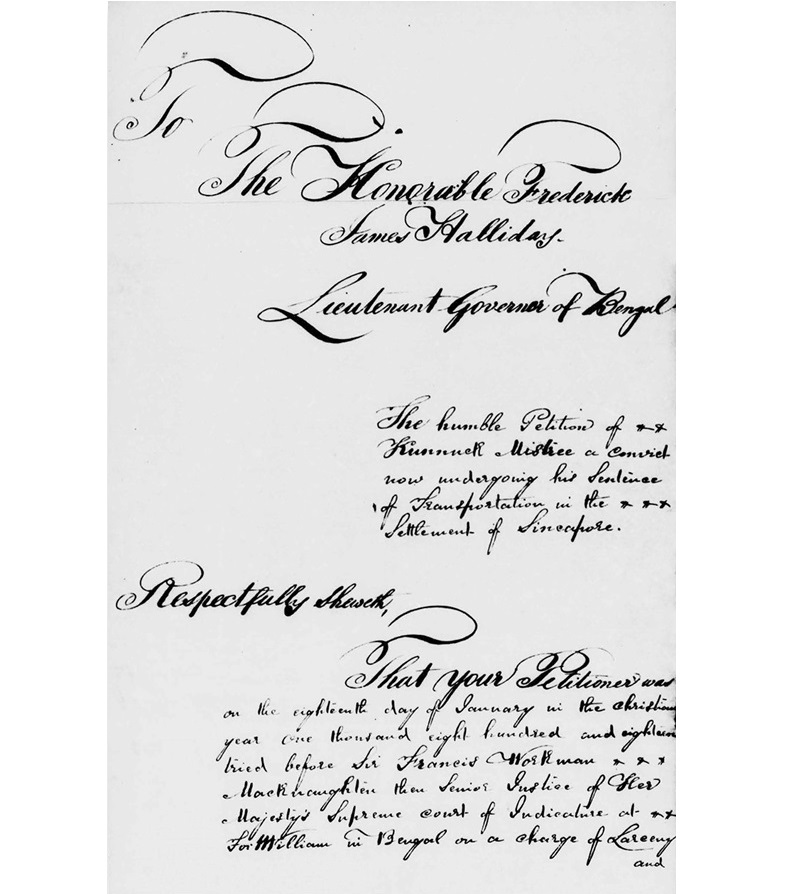

It wasn’t until two years later that a petition was submitted by Mistree’s solicitor, which was forwarded by the Governor of Singapore to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal on 23 December 1857.35 In his petition, Mistree presented himself, not without reason, as someone of impeccable character ever since his days in Bencoolen. The petition described in detail Mistree’s journey from Fort William in Calcutta to Fort Marlborough in Bencoolen and then to Singapore:

“That your Petitioner having by reason of good behaviour won the good opinion of the parties in charge of the convict establishment at Fort Marlborough was employed in the convict hospital as dresser, in the act of which he has attained considerable experience… and in consequence of good behaviour enjoyed many comforts derived to the greatest body of convicts… consequently removed to Sincapore [sic] where he continued to serve in the convict hospital in the capacity of a dresser…”36

The petition is the most detailed source of the key highlights of Mistree’s life since being sent to Bencoolen. It laid down several reasons why Mistree should be pardoned, mentioning his age (70 years) and the fact that he had already served banishment for 38 years.37

A petition in 1857 from Kunnuck Mistree’s solicitor to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, laying down his case for a free pardon. The document is the most detailed source of the key highlights of Mistree’s life since being sent to Bencoolen. Attached to the petition were copies of certificates vouching for his conduct, character references as well as his employment history. Mistree was granted a full pardon in January 1858. Collection of the National Archives of Singapore. (Media no.: SSR/S026_00750).

A petition in 1857 from Kunnuck Mistree’s solicitor to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, laying down his case for a free pardon. The document is the most detailed source of the key highlights of Mistree’s life since being sent to Bencoolen. Attached to the petition were copies of certificates vouching for his conduct, character references as well as his employment history. Mistree was granted a full pardon in January 1858. Collection of the National Archives of Singapore. (Media no.: SSR/S026_00750).

Another reason cited was Mistree’s desire to die in his homeland. “To a Hindoo the punishment of transportation is more terrible than death itself and the only consolation left to a Hindoo under such circumstances is the hope of returning if it be but to die on the banks of his beloved Ganges.”38

Attached to the petition were copies of certificates vouching for Mistree’s conduct, character references as well as his employment history. Senior officers, including doctors and jail staff, strongly supported Mistree’s quest for freedom. Resident Councillor Thomas Church issued a conduct certificate dated 20 September 1856 noting that the “conduct of Kunnuck Mistry has been very good. I know him at Bencoolen and also here for the last 19 years”.39

Mistree’s petition was successful and in January 1858, he was granted a full pardon on account of his age and stellar service record, allowing him to return to India.40

Although he was now able to return to his homeland, it appears that Mistree did not do so, or at least, not permanently. Instead, we see that from 1857 onwards, Mistree became more of a “settler” than a “sojourner”. Through donations of land and money, he began to give back to the country that had granted him a new lease of life.

Around 1858, Mistree is known to have donated a piece of land for “religious purposes”.41 It cannot be ascertained exactly where this land was but the Sri Sivan Temple,42 formerly located in Dhoby Ghaut, was within walking distance from Kampong Bencoolen. This might have been the Hindu temple that benefitted from Mistree’s generosity.

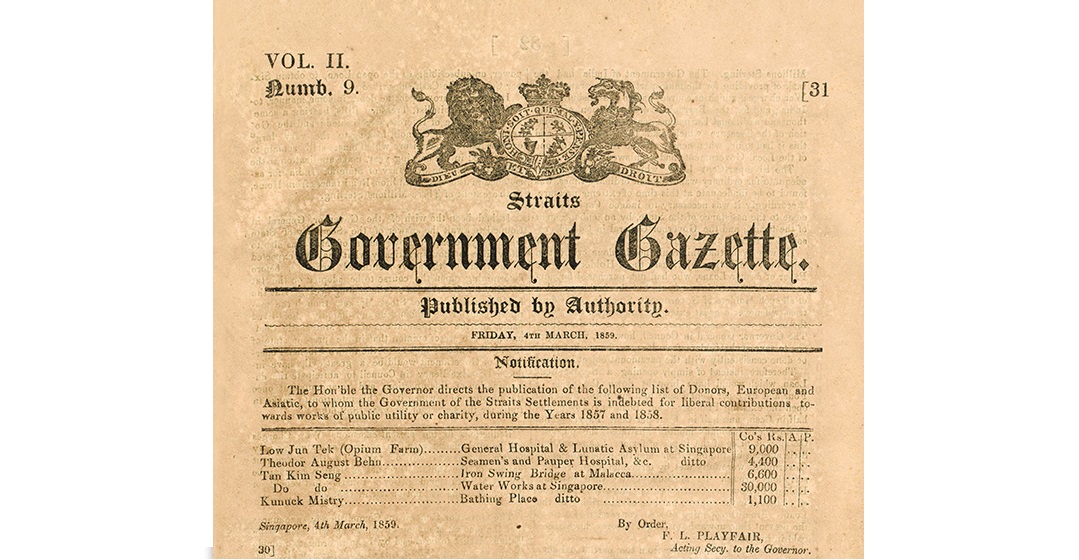

Subsequently, Mistree made a donation of 1,100 rupees towards a bathing area, earning for himself a mention in the Straits Government Gazette of 4 March 1859. It lists “Kunuck Mistry” alongside other generous donors such as Tan Kim Seng43 “to whom the Government of the Straits Settlements is indebted for liberal contributions towards works for public utility or charity, during the Years 1857 and 1858”.44 The fact that Mistree appears on the same list as the likes of prominent businessman and philanthropist Tan Kim Seng speaks volumes.

Kunnuck Mistree’s donation of Rs 1,100 towards a bathing area was announced in the Straits Government Gazette of 4 March 1859. It mentions “Kunuck Mistry” alongside other donors such as Tan Kim Seng. Image reproduced from Straits Settlements. (1859, March 4). Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 2 (9). Singapore: Mission Press. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B02969339H).

Kunnuck Mistree’s donation of Rs 1,100 towards a bathing area was announced in the Straits Government Gazette of 4 March 1859. It mentions “Kunuck Mistry” alongside other donors such as Tan Kim Seng. Image reproduced from Straits Settlements. (1859, March 4). Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 2 (9). Singapore: Mission Press. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B02969339H).

There are other signs that Mistree’s social standing had risen within Singapore society. In 1857, notices were published in the newspapers containing the names of people eligible to stand for election as municipal commissioners as well as vote for them. In order to qualify, they should pay taxes amounting to at least 25 rupees annually. The name “Kanaka Maistry” appears on the list.45

Why did Mistree not return to India to spend his remaining days as he had petitioned? Having left India under shameful circumstances and after being away for so long, Mistree, who was Hindu, would have lost his caste and like most convicts, would have nothing to look forward to in India.46 After a little over three decades in Singapore, Mistree had a new life, a successful business and a family. Age was also not on his side as Mistree was already in his 70s. In addition, his quest for a pardon appeared to have earned him respectability and the status of a free man.

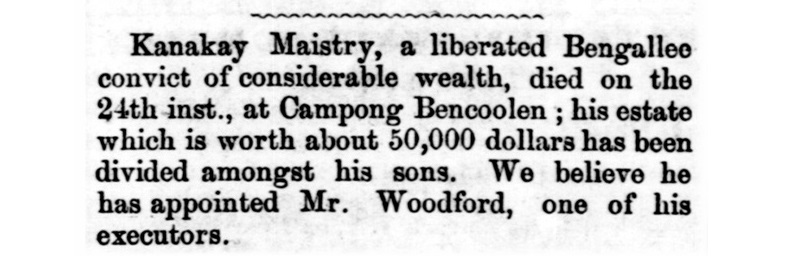

On 27 July 1865, a death notice published in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser announced the passing of Mistree on 24 July 1865:

“Kanakay Maistry, a liberated Bengallee convict of considerable wealth, died on the 24th inst. at Campong Bencoolen; his estate which is worth about 50,000 dollars has been divided among his sons.”47

Kunnuck Mistree’s death on 24 July 1865 was published in the press. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 27 July 1865, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kunnuck Mistree’s death on 24 July 1865 was published in the press. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 27 July 1865, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The amount of his estate was considered substantial at the time, and is even more remarkable given that the majority of convicts died penniless and in ignominy.

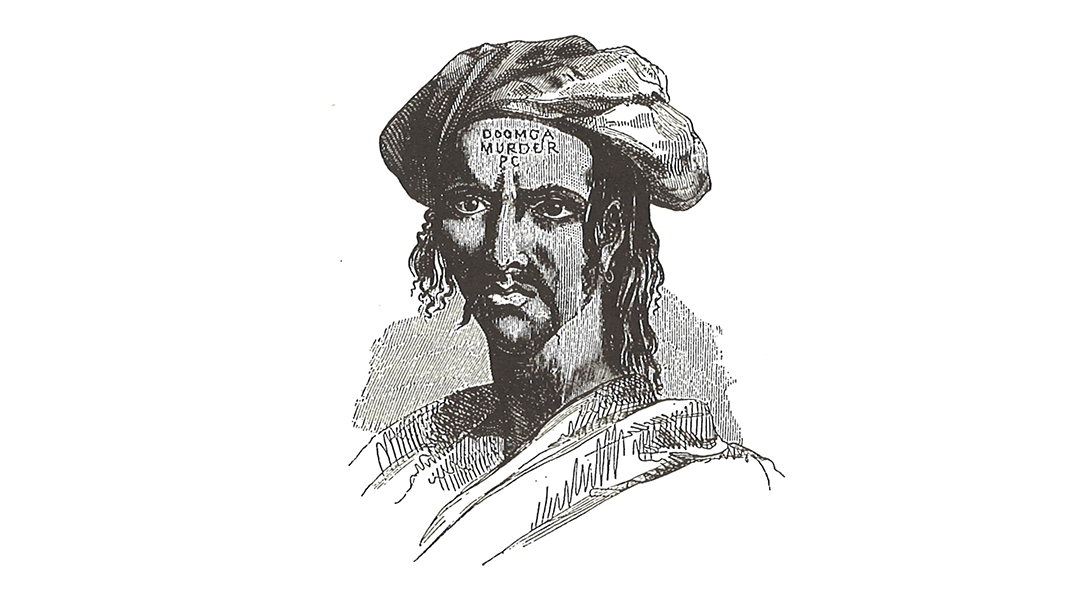

As part of their punishment, all life convicts had their name, crime and date of sentence tattooed on their foreheads in the vernacular before being transported from India. To hide this, former convicts would wear a headgear that was pulled down to cover their foreheads.48 Although Mistree would have borne this permanent mark, he did not let his convict past define him. Instead, he rose above his challenging circumstances and became a man of substance. It is possible that Mistree’s descendants still live in Singapore today, unaware of his remarkable and inspiring story.

Indian convicts were tattooed on the forehead with the crime they had committed. Shown here is a convict branded on the forehead with “Doomga”, which means “murder” in Hindustani. Image reproduced from Marryat, F. (1848). Borneo and the Indian Archipelago: With drawings of Costume and Scenery (p. 215). London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013523F).

Indian convicts were tattooed on the forehead with the crime they had committed. Shown here is a convict branded on the forehead with “Doomga”, which means “murder” in Hindustani. Image reproduced from Marryat, F. (1848). Borneo and the Indian Archipelago: With drawings of Costume and Scenery (p. 215). London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013523F).

Vandana Aggarwal is a teacher and a freelance journalist. An active citizen archivist for the National Archives of Singapore, she is the author of Voice of Indian Women: The Kamala Club Singapore (2018). She enjoys reading and researching about history.

Vandana Aggarwal is a teacher and a freelance journalist. An active citizen archivist for the National Archives of Singapore, she is the author of Voice of Indian Women: The Kamala Club Singapore (2018). She enjoys reading and researching about history.

NOTES

-

McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners their own warders: A record of the convict prison at Singapore established 1825, discontinued 1873, together with a cursory history of the convict establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797 (pp. 38–39). Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115) ↩

-

Kunnuck Mistree was most likely illiterate and left it to the writer to spell his name as he wished. National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00650]; Konnuckram Mittre. National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00720]; Kanak Mittery. National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00920]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00750]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project, 1858, SSR/S026_00750; National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00750]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Kunnuck Mistree’s application for a free pardon submitted in 1857 puts his age at 70 years. National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00780]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Raffles, S. (1830). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles: Particularly in the government of Java 1811–1816, and of Bencoolen and its dependencies, 1817–1824: With details of the commerce and resource of the Eastern Archipelago, and selections from his correspondence (p. 298). London, J. Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 6. ↩

-

For the definitions of the convict classes, see Tan, B. (2015, October–December). Convict labour in colonial Singapore. BiblioAsia, 11 (3), 36–41, p. 40. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00870]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Raffles, 1830, p. 299. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 1–2, 8. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 9. ↩

-

Anderson, C. (2018). The British Indian Empire, 1789–1939 (p. 213). In C. Anderson (Eds.), A global history of convicts and penal colonies. London: Bloomsbury Academic. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library. (1824, November–1825, February). Singapore: Letters from Bengal to the Resident [SSR/NL060/M3]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00770]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: In his petition, Kunnuck Mistree explains that most of the convicts undergoing sentence at Fort Marlborough “received a Pardon on the condition of their not returning again to the continent of India being free however to reside and live in any part of the Islands of the Eastern Archipelago”. Since Mistree was a life convict, he did not have the option to return to India but could have lived on in Bencoolen as a free citizen.] ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00880]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1855). M4: Singapore: Letters from Bengal to the Resident [Media no.: SSR/M004_0233]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Tyers, R. K. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then and now (p. 24). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TYE-[HIS]); Edwards, N., & Keys, P. (1988). Singapore: A guide to buildings, streets, places (p. 283). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 915.957 EDW-[TRA]); Cornelius-Takahama, V. (2016). Bencoolen Street. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library Singapore; Raffles, 1830, p. 299. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00890]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00820]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project, 1858, SSR/S026_00890. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [SSR/S026_00900]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1828). Q2: Singapore Miscellaneous [SSR/Q002_00750]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Information courtesy of Mr Charles Goh who found this land deed and shared it with me. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 41. ↩

-

Yang, A.A. (2003, June). Indian convict workers in Southeast Asia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Journal of World History, 14 (2), 179–208, p.18. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 41–42. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.St.J. (Eds.). (1921). One hundred years of Singapore: Being some account of the capital of the Straits Settlements from its foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919 (Vol. II, p. 488). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK) ↩

-

Untitled. (1847, July 22). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [SSR/S026_00910]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [SSR/S026_00800]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. viii, 161–162. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project, 1858, SSR/S026_00780. ↩

-

Page 1 advertisements column 2. (1846, March 5). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; The Singapore Free Press. (1865, July 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00720]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00640]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00770]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project, 1858, SSR/S026_00780. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00790]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). S26: Vol. I/II: Governor’s letters from Bengal [Media no.: SSR/S026_00810]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project, 1858, SSR/S026_00650. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore The Citizen Archivist Project. (1858). Z36 Singapore: Letters from Governor [Media no.: SSR/Z036_00240]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Sri Sivan Temple was demolished in 1983 to make way for the construction of Dhoby Ghaut MRT station. It was relocated next to Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple on Serangoon Road, before it was consecrated at its present site in Geylang East on 30 May 1993. ↩

-

Tan Kim Seng was a prominent businessman and philanthropist of his time. In 1857, he donated a large sum of money to build Singapore’s first reservoir and waterworks. To commemorate Tan’s generous contribution, the Municipal Commissioners erected the Tan Kim Seng Fountain in Fullerton Square in 1882. The fountain was moved to the Esplanade Park on Connaught Drive in 1925. It was gazetted as a national monument in 2010. ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1859, March 4). Straits Settlements government gazette, 2 (9). Singapore: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore (p. 32). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO); Page 1 advertisements column 1. (1857, November 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 9. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 27 Jul 1865, p. 2. ↩

-

Anderson, C. (2003, August 1). The execution of Rughobursing: The political economy of convict transportation and penal labour in early colonial Mauritius. Studies in History, 19 (2), 185–197, p. 5. Retrieved from SAGE Journals; Anderson, C. (n.d.). Asia and Mauritius: Penal transportation in East India co., 1787–1863. Retrieved from convictvoyages.org; McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 12. ↩