A Beastly Business: Regulating the Wildlife Trade in Colonial Singapore

The 1933 Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee represents a failed attempt to regulate the buying and selling of wildlife in pre-war Singapore, says Fiona Tan.

Even in the late 1950s, Rochor Road remained the go-to place for pet birds and, in this case, even a pet leopard. Tong Seng Mun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Even in the late 1950s, Rochor Road remained the go-to place for pet birds and, in this case, even a pet leopard. Tong Seng Mun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Amid growing public concerns about animal welfare in Singapore in the early decades of the 20th century, Straits Settlements Governor Cecil Clementi convened a committee in 1933 to examine the import and export trade of wild animals. Completed at the end of 1933 and presented to the Legislative Council in April 1934, the resulting 21-page report was one of the earliest and most comprehensive efforts to investigate the wildlife trade in Singapore. The report, however, failed to lead to improvements, illustrating the challenges faced by the British colonial government of the day in regulating the wildlife trade on the island. The lack of political will, the rise in smuggling and the increasing international demand for exotic animals scuttled efforts and exacerbated the problem.

The “Beastly Business” of the Wildlife Trade

The wildlife trade in island Southeast Asia existed long before the arrival of the Europeans in this part of the world.1 From elephants used in royal processions, to birds kept as pets or killed for their plumage, to the capture and release of animals for religious purposes – the sale of wildlife had been part and parcel of life in Southeast Asia for centuries. However, the rise of animal acts, travelling circuses, zoological gardens and pet shops in Europe and America in the 19th century further fuelled the international trade in exotic live animals. As a key trading port in the region, colonial Singapore – strategically located along the East-West trade route between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean – developed into one of the most important centres for the international wildlife trade.

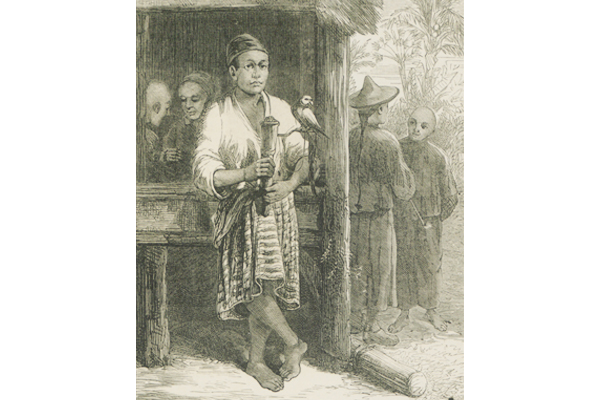

An 1872 print of a Malay bird seller waiting for steamers to arrive so that he could sell his birds to disembarking passengers. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An 1872 print of a Malay bird seller waiting for steamers to arrive so that he could sell his birds to disembarking passengers. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

As early as 1839, traveller and Orientalist Thomas John Newbold described how the Malays were “admirable snarers” of birds and wild animals.2 And in 1878, during his visit to Southeast Asia, American zoologist William Hornaday remarked, “had I been a showman or collector of live animals, I could have gathered quite a harvest of wild beasts in Singapore”. Tigers, rhinoceroses and orangutans were worth more than $100 each, while tapirs and slow lemurs could be bought for $2 per animal.3

Europeans and Americans began to make inroads into the wildlife trade scene in Southeast Asia in the late 19th century. In his memoir, American animal collector Charles Mayer described how he broke the local monopoly in Singapore by going directly to Palembang, a city in Sumatra, to collect animals. These animals were stored temporarily in a house on Orchard Road in Singapore before being shipped to American circuses or Australian zoos.4 American hunter, animal collector, actor and producer Frank Buck, who starred in the 1932 film Bring ’Em Back Alive – about his animal collecting efforts – had a similar modus operandi in place during the interwar years. He maintained a compound in Katong to house his wild animals while he travelled to Borneo, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies to hunt.

Despite the entrance of these foreign animal dealers, local animal traders continued to play an important role. In fact, there was sometimes a symbiotic relationship between foreign animal dealers and local animal traders, as seen in Buck’s accounts of his dealings with Chop Joo Soon Hin, a bird shop on North Bridge Road. Buck described the trader as an “old friend” who often provided him with information about auctions of exotic wildlife.5 However, unlike foreign animal dealers such as Mayer and Buck, these local traders left minimal archival traces of their activities.

Colonial Office records reveal that Singapore was the centre of the thriving wildlife trade in 1933, making up almost all the exports of birds and other animals, and importing at least 60 percent of birds and almost 98 percent of other animals compared to other territories in the Straits Settlements and British Malaya.6 The exports to Europe and North America also reflected how Singapore’s wildlife trade was plugged into the international demand for exotic animals.

The lackadaisical and indifferent attitudes towards the wildlife trade began to change as animal welfare movements became active during the colonial period. Some of the strongest critics of the wildlife trade were also champions of animal welfare and were among the most influential members of society. They included people like prominent businessman Tan Cheng Lock, a vocal member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council who likened the “cruel commercial exploitation of wild life” in Singapore to a “slave trade” in these “poor denizens of the forest”.7

The heightened interest in animal welfare issues during the interwar period was also evident from the interest it aroused during Legislative Council proceedings in the late 1920s and well into the 1930s. In 1927, a five-man committee was appointed to investigate the alleged prevalence of cruelty to animals. The committee produced a four-page report that described the situation at bird shops, abattoirs and ports. Although the report concluded there was “not a prevalence of cruelty” except for “accidents” caused by “carelessness”, not everyone agreed with this finding.8

In 1928, in response to that report, Tan Cheng Lock spoke up on the subject of “humane slaughtering” of animals.9 The next year, he and fellow Legislative Council member Husein Hasanally Abdoolcader advocated an update to the Ordinance on Cruelty to Animals, which resulted in a new Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Bill presented to the Legislative Council in 1930.10

This animal welfare movement was not simply about people’s sentiments towards animals. The British viewed it as a “mark of civilisation” that differentiated them from the “barbaric” Asians. In 1924, a letter to The Straits Times roundly criticised the “mental attitude of the Asiatics” in disparaging terms, claiming that they had allegedly ignored a crippled dog that had been run over and was lying in front of a Chinese house and within 50 yards of the Siglap police station. The letter writer eventually shot the dog to put it out of its misery.11

Although Europeans and Americans were also involved in the wildlife trade, the voices disparaging the wildlife trade tended to blame it on non-Europeans, commenting that the “disgraceful cruelty” was perpetuated just to “fill the pockets of those, most of whom (perhaps all), are not even British subjects”.12 The countless reports of Asians being fined for cruelty towards animals also reflected the widespread stereotypical view of the callous Asian vis-à-vis the enlightened British.13 The involvement of Europeans and Americans in the illegal animal trade was hardly reported, pointing to the racial bias and discrimination faced by the Asian community.

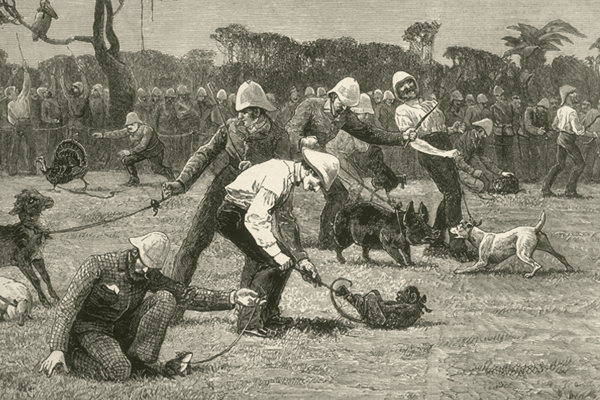

Animals were also used as a form of entertainment. Shown here is a group of European men using their pets to compete in an animal race. This print titled “A Menagerie Race at Singapore” was first published in the 20th August 1881 issue of British newspaper, The Graphic. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Animals were also used as a form of entertainment. Shown here is a group of European men using their pets to compete in an animal race. This print titled “A Menagerie Race at Singapore” was first published in the 20th August 1881 issue of British newspaper, The Graphic. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Legislating the Protection of Wildlife

Legislation to protect wildlife in the Straits Settlements dates back to 1884, when the Wild Birds Protection Ordinance was passed. The Wild Animals and Birds Protection Ordinance issued in 1904, which superseded the 1884 legislation and now included animals, vested the government with the power to declare closed seasons for hunting certain wildlife. These laws, however, only prohibited hunting and did not address the inherent problems related to the trade in non-indigenous wildlife. Only after pressure from officials in the Dutch East Indies and London did the Straits Settlements government take action to implement legislation protecting non-native species.

Between 1918 and 1925, practically all the wild animals exported from the Dutch East Indies made their way into Singapore, with the percentage never dipping below 80 percent. In addition to live animals, Singapore was also the principal port of destination for products derived from wild animals, such as rhinoceros horns, ivory, antlers, feathers and animal skins.14

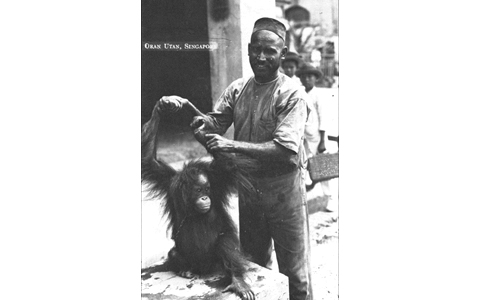

In 1928, Karel Willem Dammerman, Director of the Zoological Museum in Buitenzorg (now Bogor) and Chairman of the Netherlands Indies Society for the Protection of Nature, wrote to Carl Boden Kloss, Director of the Raffles Museum, to enquire if the latter could help stop the illegal importation of orangutans into Singapore. Willem Daniels, Consul-General for the Netherlands, followed up with an official letter in 1929 when he asked that Singapore “consider the desirability of legislative action prohibiting the importation into the Colony of orangutans”.15

Orangutans were illegally imported into Singapore in the early decades of the 20th century. Their continued smuggling from the Dutch East Indies was an impetus for the 1933 Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Orangutans were illegally imported into Singapore in the early decades of the 20th century. Their continued smuggling from the Dutch East Indies was an impetus for the 1933 Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In response, the British colonial government passed laws to limit wildlife trade. During the first reading of the proposed Wild Animals and Birds (Amendment) Bill in the Legislative Council meeting on 24 March 1930, which sought to prohibit the unlicensed importation of orangutans, Attorney-General Walter C. Huggard said that the “object of this amending Bill… is to enable this Government to co-operate with the Government of the Netherlands East Indies”.16 By 1933, the list of animals and birds prohibited for importation from the Dutch East Indies under the Schedule of the Wild Animals and Birds Ordinance had increased to 28 species from just the solitary orangutan previously.17

Within British Malaya, the conservationist movement was led by Theodore Hubback, a Pahang planter and former big-game hunter who became an “indefatigable champion of Malayan wildlife”.18 As Chairman of the Wild Life Commission of Malaya in 1930, Hubback conducted interviews in Singapore and throughout the various states of Malaya between August 1930 and March 1931, gathering accounts from Europeans and Malays as well as elite Chinese and Indian residents on wildlife issues.

In Singapore, the commission unanimously agreed on the need to regulate and license wild animal and bird shops operating on the island. In February 1931, Hubback had accompanied Colina Hussey, Vice-President of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, on a visit to various bird and animal shops owned by Asians that were located along Rochor Road and North Bridge Road. Hubback concluded that there was “serious overcrowding” as well as the presence of birds, such as the crowned pigeon, that were prohibited for export from the Dutch East Indies.19

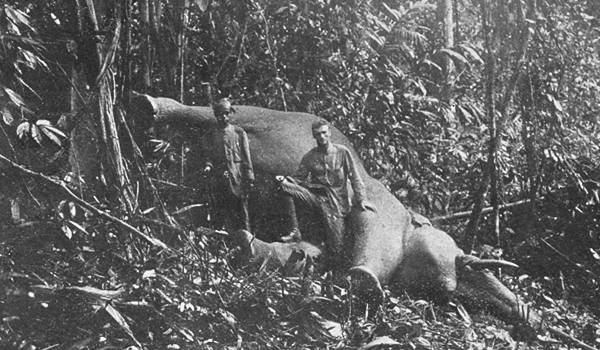

Theodore Hubback (right) was a Pahang planter and former game hunter. Here he is seen posing with a dead elephant. Hubback later became an “indefatigable champion of Malayan wildlife” and Chairman of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee. Image reproduced from Hubback, T.R. (1912). Three Months in Pahang in Search of Big Game (between pp. 58 and 59). Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 799.295113 HUB; Accession no B02835767E).

Theodore Hubback (right) was a Pahang planter and former game hunter. Here he is seen posing with a dead elephant. Hubback later became an “indefatigable champion of Malayan wildlife” and Chairman of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee. Image reproduced from Hubback, T.R. (1912). Three Months in Pahang in Search of Big Game (between pp. 58 and 59). Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, Limited. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 799.295113 HUB; Accession no B02835767E).

The Report of the Wild Life Commission of Malaya was published in 1932. Described as an exhaustive inquiry prepared with “extraordinary thoroughness” which reached “somewhat forbidding proportions”, the three-volume publication contained a general survey of the status of wildlife in Malaya, lists of wildlife enactments in other countries and in Malaya, and a comprehensive draft Enactment for the Preservation of Wild Life.20 Although the report briefly noted the issues with the wildlife trade, it also highlighted that the magnitude of the problem in Singapore warranted a separate investigation.21

Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, Singapore, 1933. The committee was convened to inquire and report on the retail trade in wild animals and wild birds, and to ensure their humane treatment. Image reproduced from Hubback, T.R., et al. (1934). Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, Singapore, 1933. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 338.3728 SIN; Accession no.: B02978387K).

Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, Singapore, 1933. The committee was convened to inquire and report on the retail trade in wild animals and wild birds, and to ensure their humane treatment. Image reproduced from Hubback, T.R., et al. (1934). Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, Singapore, 1933. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 338.3728 SIN; Accession no.: B02978387K).

The Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee

On 21 July 1933, Governor of the Straits Settlements Cecil Clementi appointed a committee to inquire and make recommendations on “(a) The import and export trade in Wild Animals and Wild Birds in Singapore… and (b) The suitability or otherwise of the methods adopted in Singapore… for the transport, housing and care of Wild Animals and Wild Birds… so as to ensure humane treatment [of them].”22 The Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee comprised Chairman Theodore Hubback; and members Frederick Nutter Chasen, Director of the Raffles Library and Museum; Tan Cheng Lock; Municipal Commissioner Harry Elphick; and Municipal Veterinary Surgeon James Thompson Forbes.23

The committee’s terms of reference were to inquire and report on the retail trade in wild animals and wild birds, “with special reference to the control and supervision desirable so as to ensure humane treatment for them”. The Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee was completed on 22 December 1933 and presented before the Legislative Council on 16 April 1934.24

The scope of the committee’s investigations was limited to businesses such as the Asian animal traders on Rochor Road, which had been the subject of “much adverse criticism… in the local press”. Although private zoos such as those owned by Herbert de Souza on East Coast Road and William Basapa in Punggol were mentioned, these were considered “beyond the scope of small retail traders”.25

The committee’s focus on the Rochor Road shops and the conspicuous absence of foreign animal dealers mirrored the government’s discriminatory attitudes towards non-Europeans involved in the business. Unlike the Rochor Road traders, the committee believed that private zoo proprietors such as de Souza and Basapa and foreign animal dealers like Buck did not ill-treat their animals, and hence excluded them from specific scrutiny and investigation. To support this, the report cited Government Veterinary Surgeon George Rocker, who said that “the bona fide agent and dealer in wild animals for zoological gardens and collectors usually carrie[d] on his business in a satisfactory manner… [because] the high monetary value of his stock for an animal kept under unfavourable conditions rapidly depreciates in marketable worth”.26

This assumed distinction between “bona fide” agents and “unscrupulous” Asian animal traders, however, reflected the committee’s personal biases rather than reality. One of the shops the committee took to task was Chop Joo Soon Hin, operating at 532 North Bridge Road and mentioned in Frank Buck’s Bring ’Em Back Alive as a key local animal shop frequented by American wildlife dealers.27 As a supplier to well-known animal dealers, it is difficult to imagine how the proprietor of Chop Joo Soon Hin could not be considered a bona fide agent who was aware of the value of his animals.

Moreover, developments in the late 1930s revealed that the private zoos which the committee exempted from scrutiny were not necessarily above the ill-treatment of animals. For instance, in 1938, the Singapore Rural Board commented on the “appalling stench” emanating from the poorly ventilated cages of the Punggol Zoo.28

The Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee cited how Asians attempted to strike back – on the rare occasion that they did. It mentioned a letter submitted by four local animal traders – Chop Joo Soon Hin, Chop Kian Huat and Co, Chop Guan Kee and Chop Cheng Kee – objecting to the committee’s suggestion of a central market for the bird and small-mammal trade. In addition to their concerns regarding the “prevailing bad state of business” and the necessary readjustment of operating hours, one of their moral justifications for the rejection of a central market was that “many species of birds, such as the canary, [could not] withstand the breeze and as a result their feathers [would] wither and they [would] soon collapse”.29

The committee easily picked apart this argument by pointing out that the Asian shopkeepers neglected the welfare of other animals in their perhaps misplaced concern for the canaries which, after all, did not seem to experience any severe effects from exposure to strong winds.30 Positioning the welfare of the birds as a central argument showed a creative, but unfortunately unsuccessful, attempt by Asian dealers at pushing back.

The committee made four broad recommendations: construct a central market for the sale of animals; restructure the system of authority overseeing the wildlife trade by placing it under the governance of a central Malaya-wide body; refine legislations to prosecute smugglers of wildlife; and issue licences for the importation of protected species of wildlife and the operation of private zoos in Singapore.31

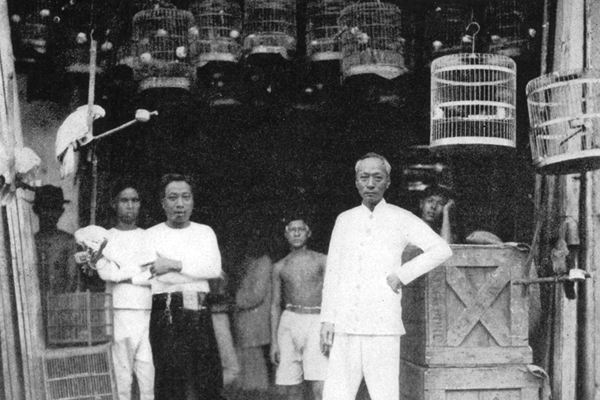

Chop Joo Soon Hin at 532 North Bridge Road was one of the shops that the 1933 Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee investigated. The shop was frequented by American animal dealers. Image reproduced from Buck, F.H.. (1922, August). A Jungle Business. Asia: The American Magazine of the Orient, 22 (8), 633–638.

Chop Joo Soon Hin at 532 North Bridge Road was one of the shops that the 1933 Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee investigated. The shop was frequented by American animal dealers. Image reproduced from Buck, F.H.. (1922, August). A Jungle Business. Asia: The American Magazine of the Orient, 22 (8), 633–638.

The Reluctance to Regulate

Despite favourable public opinion lauding the formation of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, none of the report’s recommendations were subsequently implemented.

One of the main reasons for its failure was the reluctance at various levels of government – comprising the Legislative Council, the Executive Council and the Municipal Commission – to take responsibility for, and to implement, the recommendations. The Municipal Commissioners discussed the committee’s recommendations in a meeting on 4 May 1934 but concluded that “expenditure from the Municipal Fund for the establishment of a market for the purposes proposed [that is, the sale of birds and small mammals not for food] would be illegal”.32 As The Straits Times commented:

“The report followed years of agitation in the Press… against a very disgraced state of affairs. There had been almost complete unanimity in urging that something should be done… But the optimists failed to make allowance for the reluctance of public bodies to undertake anything which they might conveniently push on to someone else. Apparently the ball of responsibility was tossed to and fro between the Government and the Municipality until public interest in the question became dim.”33

There was also little financial incentive to regulate the wildlife trade and its associated products as these were not economically valuable to Singapore. In 1933, the value of imports of “Animals not living for food” was $172,377 while exports totalled $31,935. This was about 0.05 percent of the total value of imports into the colony and just 0.009 percent of total exports. In comparison, rubber and gutta percha collectively made up about 6 percent of total imports and 21 percent of total exports.34 Furthermore, the revenue received from licensing shops selling wild animals and birds in 1933 was about $78, a mere pittance when compared to the revenue from opium that year, which was almost $4.3 million.35

The proposal of a central agency to oversee wildlife trade in the whole of Malaya was also seen as a direct challenge to the decentralisation policy championed by Governor Cecil Clementi Smith beginning in 1930.36 The report was viewed as another instance of “kick[ing] against the bricks” of decentralisation and was not to be taken too seriously.37

The personality and methods of Hubback, the committee’s chairman, did not win him many allies or supporters either. He was perceived as having a “lack of balance” and “misdirected enthusiasm”.38 His insistence on corresponding directly with members of parliament in England, rather than following the official protocol of holding prior discussions with the Governor of the Straits Settlements and the High Commissioner in Malaya, created further tensions.39

Although there were laws to control the smuggling of wild animals and birds from the Dutch East Indies by the 1930s, it was difficult to regulate an illicit trade along a porous border that had historically been difficult to police. The inability to prosecute the individuals in possession of such animals unless proof of illegal importation was obtained meant that many smugglers went scot-free.40

The Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee also never addressed the issue of demand. The committee observed that despite extant legislation aimed at reducing the import of protected species from the Dutch East Indies, the fact that they still turned up in wildlife shops on Rochor Road in Singapore suggested that the smuggling was “considerable”.41

In addition to the demand from zoos and circuses in Europe, America and Australia, the popularity of the jungle film genre in the 1930s created more interest for live exotic animals. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Buck’s Jungle Show, with live wild animals shipped from Singapore, was the highlight of the Malay Village in the Colonial Section of the British pavilion.42

A live elephant, nicknamed Babe, being transported from Singapore to San Francisco in the 1920s. Image reproduced from Buck, F.H., & Anthony, E. (1930). Bring ’Em Back Alive (facing p. 220). Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Pub. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSEA 799.2 BUC).

A live elephant, nicknamed Babe, being transported from Singapore to San Francisco in the 1920s. Image reproduced from Buck, F.H., & Anthony, E. (1930). Bring ’Em Back Alive (facing p. 220). Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Pub. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSEA 799.2 BUC).

The attempt in 1933 to curb the wildlife trade in colonial Singapore was fraught with difficulties. In addition to the laissez-faire attitude of the government of the day, and the personal differences between Hubback, the Chairman of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, and the Governor of the Straits Settlements also did not help matters.

Furthermore, the demand for exotic wild animals and Singapore’s role as an important centre for the international wildlife trade meant that even if the Straits Settlements government was willing to act against its preferences and had stepped in to regulate the trade, the high demand and the prevalence of smuggling could have thwarted attempts at regulation. The failure of the committee to effect significant change reflects the complex and multilayered nature of the wildlife trade that existed in Singapore at the time.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Records Management department at the National Archives of Singapore. She started her journey with the archives as an undergraduate studying history, poring over microfilms at the old Archives Reading Room. This research formed the basis of her dissertation, which is abridged in this article.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Records Management department at the National Archives of Singapore. She started her journey with the archives as an undergraduate studying history, poring over microfilms at the old Archives Reading Room. This research formed the basis of her dissertation, which is abridged in this article.

NOTES

-

Elephants were imported and traded in the region before colonial rule from places as near as Java and Melaka to as far away as India. See Boomgaard, B. (1997). Hunting and trapping in the Indonesian archipelago, 1500–1950. In P. Boomgaard, F. Colombijn & D. Henley (Eds.), Paper landscapes: Explorations in the environmental history of Indonesia (p. 195). Leiden: KITLV Press. (Call no.: RSEA 304.2809598 PAP); Andaya, B.W. (1979). Perak, the abode of grace: A study of an eighteenth-century Malay state (pp. 77–78). Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5131 AND) ↩

-

Newbold, T.J. (1839). Political and statistical account of the British settlements in the Straits of Malacca, viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore; with a history of the Malayan states on the peninsula of Malacca (Vol. II; p. 190). London: John Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 NEW; Accession no.: B03013424F) ↩

-

Hornaday, W.T. (1993). The experiences of a hunter and naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo (p. 8). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 910.4 HOR) ↩

-

Mayer, C. (1922). Trapping wild animals in Malay jungles (pp. 25–30, 33–34, 93). London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 799.29595 MAY-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29267011F) ↩

-

Buck, F., & Anthony, E. (1930). Bring ’em back alive (p. 18). Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Pub. (Call no.: RSEA 799.2 BUC) ↩

-

For the detailed breakdown, see Table 1 in Tan, F. (2014). The beastly business of regulating the wildlife trade in colonial Singapore. In T. Barnard (Ed.), Nature contained: Environmental histories of Singapore (p. 151). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 304.2095957 NAT) ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (p. B43). (1933, March 6). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/67; Microfilm no.: NL1126). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (pp. C206–207). (1927, October 31). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/61; Microfilm no.: NL1123). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (pp. B93–B94). (1928, August 27). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/62; Microfilm no.: NL1124). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (pp. B125–B127). (1929, October 7). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/63; Microfilm no.: NL1124); Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (p. B32). (1930, May 12). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/64; Microfilm no.: NL1125). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Humanity in the east. (1924, August 10). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cruelties of the bird trade. (1931, October 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A plea for the wild. (1931, October 28). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Further instances of such reports in the 1930s include A callous Chinese: Exemplary sentence for cruelty to ducklings: Exemplary sentence for cruelty to ducklings. (1930, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 12; Cruelty to animals: Indian menagerie owner fined. (1930, November 27). The Straits Times, p. 12; Cruelty to birds: Two Chinese fined for overcrowding. (1933, June 15). The Straits Times, p. 16; Smile disappeared: Chinese fined for cruelty to birds. (1934, January 13). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dammerman, K.W. (1929). Preservation of wildlife and nature reserves in the Netherlands Indies (pp. 88–91). Weltevreden: Emmink. (Call no.: RCLOS 591.9598 PAC) ↩

-

Prohibition of the importation of orang utan from Dutch East Indies into the Straits Settlements: Letter from K.W. Dammerman to C. Kloss. (1928, September 11). (Record reference no.: C.S.O. Museums 8366/1928; Microfilm no.: MSA 1139/10). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore; Prohibition of the importation of orang utan from Dutch East Indies into the Straits Settlements: Letter from W. Daniels to Colonial Secretary of Straits Settlements. (1929, August 16). (Record reference no.: C.S.O. Museums 8366/1928; Microfilm no.: MSA 1139/10). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (p. B19). (1930, March 24). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/64; Microfilm nos.: NL1124, NL1125). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1933, June 30). Straits Settlements government gazette (Gazette Notification 1283). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfilm nos.: NL1240, NL1241) ↩

-

Kathirithamby-Wells, J. (2005). Nature and nation: Forests and development in Peninsular Malaysia (pp. 198–199). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (Call no.: RSEA 333.75095951 KAT) ↩

-

Malaya. Wild Life Commission. (1932). Report of the Wild Life Commission (p. 46). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 591.9595 MAL; Microfilm nos.: NL26030 [v. 1]; NL9935 [v. 1–v. 3]; NL31934 [v. 3]) ↩

-

The wild life report. (1932, August 15). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hubback, T.R., et al. (1934). Report of the Wild Animals and Wild Birds Committee, Singapore, 1933 (p. 17). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 338.3728 SIN; Accession no.: B02978387K ; Microfilm no.: NL26231) ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1933, July 21). Straits Settlements government gazette (Gazette Notification 1412). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfilm nos.: NL1240, NL1241) ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council (p. B32). (1930, March 24). (Accession no.: R.M.I E/64; Microfilm nos.: NL1124, NL1125). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Proceedings of Straits Settlements Legislative Council, 24 Mar 1930, p. B32. ↩

-

Hubback et al., 1934, pp. 14–15. Also see The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 20 Oct 1931, p. 8. ↩

-

‘Appalling stench’ in Ponggol zoo cages. (1938, November 11). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Minutes of the Proceedings of the Municipal Commissioners (p. 178). (1934, May 4). (Microfilm no.: NA436). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lost, stolen or strayed. (1935, September 13). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The percentage was calculated based on total imports of $330,661,128 and total exports of $346,471,451. The total import of raw rubber and gutta percha was estimated at $22,251,167 and total export estimated at $73,726,509. Statistics from The Foreign Trade of Malaya. (1934). See Straits Settlements. (1933). Straits Settlements annual reports (pp. 700, 702–703). (Accession no.: R.M.I D/73; Microfilm no.: NL2922). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

The sum of $78 was based on the $1 annual licence fee according to the Animal and Bird Shop By-Laws and the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Department Annual Report figure of 78 shops being licensed in 1933. The revenue from opium licensing is taken from Straits Settlements. (1934). Straits Settlements Blue Book 1933 (p. 85). (Accession no.: RM: I F/64; Microfilm no. NL3143). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Smith, S.C. (1995). British relations with the Malay rulers from decentralization to Malayan independence 1930–1957 (pp. 22–23). Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5105 SMI) ↩

-

Note by E. Gent. (1934, January 16). Preservation of wildlife. (Reference no.: CO717/96/1; 13329/1933). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Letter from John Kempe to Colonial Office. (1934, April 29). Preservation of wildlife. (Reference no.: CO717/104/13, 33359/1934). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Letter from T. Hubback to C. Clementi. (1931, July 14). Preservation of game. (Reference no.: CO717/78/13; 82352/1931). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Malay village at world fair. (1938, December 18). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩