Nature Conservation in Singapore

Balancing biodiversity conservation with urban development is a hot-button issue in land-scarce Singapore. Ang Seow Leng examines how this process has played out over the last 200 years.

As a result of habitat loss, the Sunda pangolin has become a critically endangered species in Singapore. Pangolins are heavily trafficked and are poached for their scales and meat. In the wild, these mammals are mainly found in the nature reserves and adjacent nature parks of Singapore. Courtesy of Wildlife Reserves Singapore.

As a result of habitat loss, the Sunda pangolin has become a critically endangered species in Singapore. Pangolins are heavily trafficked and are poached for their scales and meat. In the wild, these mammals are mainly found in the nature reserves and adjacent nature parks of Singapore. Courtesy of Wildlife Reserves Singapore.

Even in tiny, highly urbanised Singapore, nature still has the capacity to surprise. In May 2019, the National Parks Board (NParks) revealed that more than 40 species of animals, potentially new to Singapore, were discovered during a comprehensive survey carried out at the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve between 2014 and 2018. The reserve is home to 40 percent of spider species, 84 percent of amphibian species and 56 percent of mammal species.1

More recently, in September 2020, it was announced that 20 new animal species had been found on Pulau Ubin during the first comprehensive survey of biodiversity on the island, including three species of bats, the buff-rumped woodpecker as well as species of butterflies, dragonflies, damselflies, grasshoppers, crickets and katydids.2

Despite extensive development, Singapore still has immensely diverse wildlife, including critically endangered species like the Sunda pangolin, the Raffles’ banded langur and the straw-headed bulbul. The 720-square-kilometre of land boasts more than 2,000 native plant species, some 57 mammal species, 98 reptile species, 25 amphibian species, 355 species of birds and over 282 species of butterflies. There are also hundreds of fish species living in intertidal mangroves and mudflats, and many more other species.3

Preserving the natural environment from human encroachment, however, took deliberate effort. In fact, just 30 years after the establishment of a trading settlement on the island in 1819, half of Singapore’s forests had been cleared for the planting of commercially viable cash crops such as gambier and pepper and for development to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population.4

The physical landscape was also reshaped to support urbanisation and commerce. Hills were levelled, swamps filled and coastlines extended. The first effort at land reclamation was carried out in 1822 on the swampy grounds around South Boat Quay.5 As a result, little remains of the original rainforests, mangrove swamps and other ecosystems that greeted Stamford Raffles when he arrived in 1819.

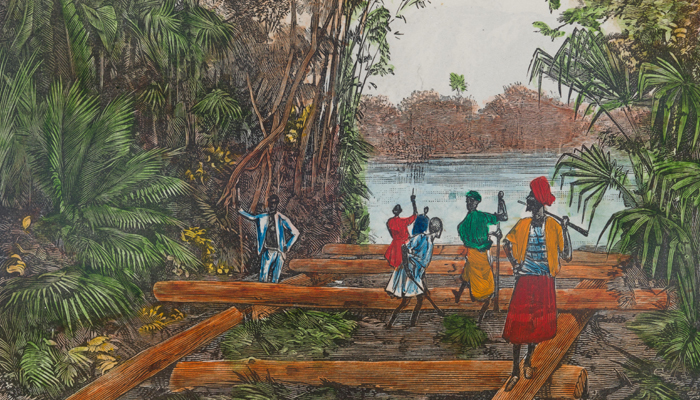

“Rolling Timber Through Jungle to River, Straits Settlements Court”, a wood engraving published in the Illustrated London News, 1886, depicting the economic opportunities of the forests of the Straits Settlements. By the late 19th century, much of the primary forest in Singapore had been cleared for cash crops and a growing migrant population. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

“Rolling Timber Through Jungle to River, Straits Settlements Court”, a wood engraving published in the Illustrated London News, 1886, depicting the economic opportunities of the forests of the Straits Settlements. By the late 19th century, much of the primary forest in Singapore had been cleared for cash crops and a growing migrant population. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The tension between preserving nature and development is particularly acute in Singapore because of its small size. Southeast Asia is a biodiversity hotspot where many endemic species, such as the Sumatran rhinoceros and Malayan tiger, are under threat. In 2016, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Species Survival Commission warned that “there is an alarming concentration of critically endangered species in the [Southeast Asian] region”.6

Speaking in Parliament in February 2021, Minister for National Development Desmond Lee noted that “Singapore is committed to stewarding and protecting its green spaces, but the Republic’s physical constraints mean that some undeveloped sites will have to be tapped to meet land use needs”. He added that Singapore has to “constantly balance demands and trade-offs across a wide variety of needs, including housing, green spaces, infrastructure, community facilities, workplaces, amongst others”.7

Laws Protecting Singapore’s Biodiversity

It was only in the late 19th century that Singapore began efforts to conserve the natural environment. Birds became the first wildlife in Singapore to be protected from unlicensed killing, wounding or taking when the Wild Birds Protection Ordinance was passed in 1884.8 This law followed a magistrate’s inquiry that year when it was discovered that as many as 20,000 birds of brilliant plumage had been captured by a single individual within a six-month period in 1883, and were later exported. The threat of these birds becoming extinct, as well as the widespread complaints of insects ravaging paddy fields, led to the Straits Settlements Legislative Council proposing a Wild Birds Protection Bill that would “make it an offence punishable by fine and simple imprisonment to kill or take” birds, other than those that may be lawfully shot such as game birds and birds of prey.9

Two decades later, the Wild Animals and Birds Protection Ordinance was enacted in 1904, replacing the Wild Birds Protection Ordinance. The new legislation extended protection from birds to other animals. Singapore also passed the Plumage Ordinance in 1916, which banned the import and export of plumage (this law was in force until 1970).10

In 1882, Nathaniel Cantley, then Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, conducted a survey of forests in the Straits Settlements and made recommendations for their management. He estimated that only 7 percent of the original forest were still intact at the time of the survey.11

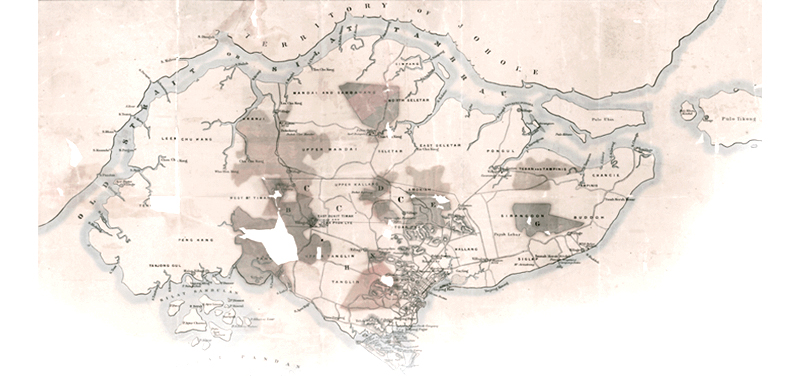

In 1882, Nathaniel Cantley, Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, proposed creating forest reserves to stop illegal deforestation. This map of the island of Singapore, dated 10 November 1882, shows the locations of the proposed forest reserves. Survey Department, Singapore, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1882, Nathaniel Cantley, Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, proposed creating forest reserves to stop illegal deforestation. This map of the island of Singapore, dated 10 November 1882, shows the locations of the proposed forest reserves. Survey Department, Singapore, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

At the time, there were no laws or regulations to offer legal protection to the forests. Cantley proposed creating forest reserves to stop illegal deforestation, identifying forest reserves for the supply of wood for general purposes, protecting mountain and river reserves where necessary, and introducing an ordinance for better conservation of the Crown forest. In 1883, the first forest reserves were identified and administered by the newly established Forest Department under the Singapore Botanic Gardens with Cantley as its first director.12

In 1908, the Forest Ordinance was finally passed. The legislation prohibited trespassing or cattle grazing in a reserved forest, and made it an offence to cut, collect or remove forest produce such as soil, minerals, plant parts, honey, wax and guano without proper authorisation. In Singapore, 15 areas were gazetted as forest reserves: Sungei Buloh, Kranji, Murai, Tuas, Choa Chu Kang, Bukit Panjang, Bukit Mandai, North Seletar, Bukit Timah, Ang Mo Kio, South Seletar, Changi, Jurong, Pandan and Sembawang.13

However, in 1925, 17 years after the enactment of the Forest Ordinance, the colonial government began questioning the value of preserving forest reserves in Singapore. The annual report on the forests of the colony for that year stated that “really effective management of the Singapore forests is possible only at a cost which the forests themselves do not seem to justify”. This was because none of the reserves were deemed to be of great value, with substantial areas leased out on temporary occupation licences to vegetable growers. The report further mentioned that the reserves could never meet the demand for timber and firewood.14

In 1931, the government deliberated over a proposal to revoke all forest reserves in Singapore because these were unable to generate revenue from timber production and were expensive to maintain. It was also difficult to prevent encroachment by illegal squatters and stop illegal cutting.15

Five years later, all forest reserves were revoked in Singapore, although selected areas like some parts of the Bukit Timah forest were protected. This was after the Commissioner of Lands reported that the forest reserves of Singapore were made up largely of “market gardens, villages and granite quarries”.16

The Raffles’ banded langur, 2020. Named after Stamford Raffles and native to Singapore and southern peninsular Malaysia, the primate was once common throughout Singapore but its population is now critically endangered. The main threat to its survival is the loss of habitat. Photo by Andie Ang. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Raffles’ banded langur, 2020. Named after Stamford Raffles and native to Singapore and southern peninsular Malaysia, the primate was once common throughout Singapore but its population is now critically endangered. The main threat to its survival is the loss of habitat. Photo by Andie Ang. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In 1939, Bukit Timah, Pandan and Kranji were re-gazetted as forest reserves and came under the management of the Director of Botanic Gardens as the Conservator of Forests.17 Bukit Timah was found to offer samples of interesting plants for research by students, while the other two reserves were mangrove forests.18

After the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), Richard Eric Holttum, then Director of the Botanic Gardens, pushed for legislation to protect the Bukit Timah forest reserve and possibly other areas as “sanctuaries for wild life of all kinds”.19 He also contributed an article in The Straits Times, explaining that the “mangrove is a land-building agent of major importance in the wet tropics”, besides being a sanctuary for plants and animals.20

In 1951, a select committee on granite quarries and nature reserves called for the inclusion of the municipal water catchment area, the Crown land including the cliff at Labrador, and the two forest reserves of Pandan and Kranji as nature reserves. As the nature reserves would be extended to mangrove swamps, the committee pointed out that the latter might contain species of extinct orchids that could have a chance of reappearing when the mangroves began regenerating. These areas also provided shelter to animals and birds not found elsewhere on the island.21

This led to the Nature Reserves Ordinance, which came into force in 1951. The law aimed to protect and preserve flora and fauna in the nature reserves and provide opportunities for their study and research within the natural environment in which they live. The ordinance evolved into the Nature Reserves Act in 1985, which was repealed and replaced by the National Parks Act in 1990.22

With growing awareness and calls for the conservation of nature areas, Singapore currently has 24 nature areas comprising the four main nature reserves – Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve – as well as 20 other areas that are subject to administrative safeguards under the Parks and Waterbodies Plan. The four nature reserves are protected under the Parks and Trees Act.23

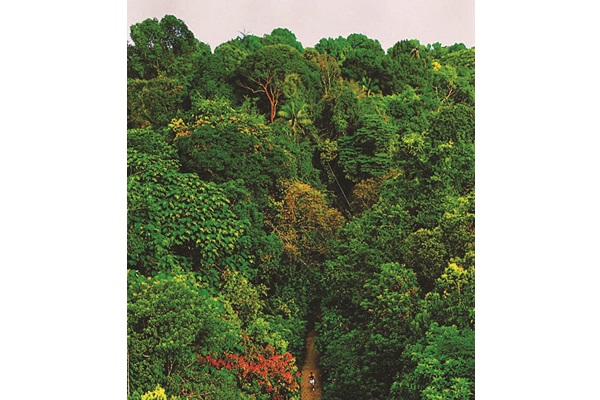

View from Jelutong Tower in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. This reserve, along with Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve, make up the four main nature reserves in Singapore. Image reproduced from Chua, E.K. (2015). Rainforest in a City (p. 21). Singapore: Simply Green. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 577.34095957 CHU).

View from Jelutong Tower in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. This reserve, along with Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve, make up the four main nature reserves in Singapore. Image reproduced from Chua, E.K. (2015). Rainforest in a City (p. 21). Singapore: Simply Green. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 577.34095957 CHU).

Nature Conservation in the Last 40 Years

A more consolidated approach towards nature conservation emerged with the formation of NParks in 1990 to manage the national parks, then comprising the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Fort Canning Park and the nature reserves. In 1996, the Parks and Recreation Department merged with NParks to streamline the management of parks under one single organisation.24

Today, NParks is responsible for propagating, protecting and preserving “the animals, plants and other organisms of Singapore and, within the national parks, nature reserves and public parks, to preserve objects and places of aesthetic, historical or scientific interest”.25 NParks also administers the following laws that protect Singapore’s flora and fauna: Animals and Birds Act; Control of Plants Act; Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act; Parks and Trees Act; and Wildlife Act.

In 1986, Singapore joined the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). It is currently among the 183 countries bound by an international agreement that regulates international trade in endangered species of wild animals and plants through a system of licences.26 During the signing of the CITES treaty, then Minister for the Environment Ong Pang Boon noted that “the [Southeast Asian] region was at the crossroads of a thriving international trade on flora and fauna, which if left unchecked could lead to the irreversible loss of valuable species”.27

Singapore has two of the world’s four species of horseshoe crabs – the coastal horseshoe crab (shown here) and the mangrove horseshoe crab. Courtesy of Ria Tan, Wild Singapore.

Singapore has two of the world’s four species of horseshoe crabs – the coastal horseshoe crab (shown here) and the mangrove horseshoe crab. Courtesy of Ria Tan, Wild Singapore.

Singapore is also a signatory to the International Convention on Biological Diversity arising from the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. That same year, the Singapore Green Plan – the nation’s first environmental blueprint – was launched to develop an economic growth model for Singapore without compromising or causing harm to the environment in any way.28 The blueprint charted the strategic directions that Singapore would adopt, looking into all areas of environmental concerns and presenting proposals to preserve, protect and enhance the environment for the future. The plan also proposed that up to 5 percent of Singapore’s land area would be set aside for protection as nature conservation areas.29

In 2002, the Singapore Green Plan 2012 was launched to better address conservation issues as new ideas and concerns had emerged in the preceding decade, such as transboundary air pollution and climate change as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. In 2006, a revised edition of the earlier green plan was released which called for establishing more parks and green linkages, and the setting up of a National Biodiversity Reference Centre (now renamed National Biodiversity Centre).30 Under the purview of NParks, the centre was established in 2006 as a “clearing house not only for centralising biodiversity data about Singapore, but also for co-ordinating and facilitating research in biodiversity and ecology issues”.31

The oriental pied hornbill, a species native to Singapore, once declined in numbers to the point of local extinction. Successful conservation efforts in recent years have seen these majestic creatures taking to the skies once again. Courtesy of Quek Yew Hock, NParks SGBioAtlas/BIOME.

The oriental pied hornbill, a species native to Singapore, once declined in numbers to the point of local extinction. Successful conservation efforts in recent years have seen these majestic creatures taking to the skies once again. Courtesy of Quek Yew Hock, NParks SGBioAtlas/BIOME.

Recent Initiatives

The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) announced in 2009 by NParks aimed to address both policy frameworks and specific measures for better planning and coordination in the sustainable use, management and conservation of Singapore’s biodiversity, taking into consideration the country’s national priorities as well as its international and regional obligations.32

The action plan was updated in 2019, incorporating input from various public sector agencies and nature groups. Close to 10 percent of Singapore’s total land area would be set aside for parks and nature conservation, up from the 5 percent proposed in the 1992 Singapore Green Plan.33

In 2015, NParks launched the Nature Conservation Masterplan to chart the course of Singapore’s future biodiversity conservation efforts. It aimed to “systematically consolidate, coordinate, strengthen and intensify the biodiversity conservation efforts outlined in [the] NBSAP”.34

More recently, in 2021, the Singapore Green Plan 2030 – spearheaded by government ministeries in charge of education, national development, sustainability and the environment, trade and industry, and transport – was unveiled.35 One of the key pillars in the green plan is the “City in Nature” strategy. This means that by 2030, Singapore would have an additional 1,000 hectares of green spaces and 160 km of park connectors, every household would live within a 10-minute walk from a park, and 1 million more trees would be planted across the island.36

Nature Society (Singapore)

While the state has played an important role in conserving nature by passing legislation and promoting government policies to green Singapore, non-governmental organisations have played an important role too. Perhaps the most prominent of these is the Nature Society (Singapore), or NSS.

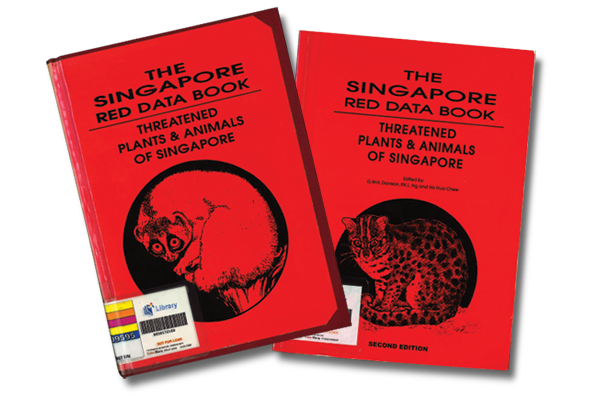

The Nature Society (Singapore) first published The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants & Animals of Singapore in 1994. It became an indispensable source of reference for conservation plans and efforts in Singapore. The publication was updated in 2008. Davison, G.W.H., Ng, P.K.L., & Ho, H.C. (Eds.). (2008). The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants & Animals of Singapore. Singapore: Nature Society. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 591.68095957 SIN).

The Nature Society (Singapore) first published The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants & Animals of Singapore in 1994. It became an indispensable source of reference for conservation plans and efforts in Singapore. The publication was updated in 2008. Davison, G.W.H., Ng, P.K.L., & Ho, H.C. (Eds.). (2008). The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants & Animals of Singapore. Singapore: Nature Society. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 591.68095957 SIN).

The NSS is one of the oldest non-governmental organisations in Singapore, with roots dating back to 1921 when its predecessor, the Singapore Natural History Society, was formed. Although the society later faded away, a new society – the Malayan Nature Society (MNS) – was established in 1940 and based in Malaya. In 1954, the Singapore section of the MNS was founded. It eventually separated from the MNS in 1991 and became an independent entity in 1992.37

Since the 1980s, the NSS has been actively working with passionate individuals and associated groups in researching, documenting, surveying and partnering with the government and other stakeholders in joint projects like the biological survey of the Central Catchment Nature Reserve and the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve.38 Over the years, the society has issued various nature conservation plans, proposals and biodiversity works and reports, and was the first to propose a Master Plan for the Conservation of Nature in Singapore in 1990. The plan, which listed protected nature reserves and relatively unknown areas of secondary forests that were noted for their rich birdlife, was referenced by the government for policymaking and planning.39

In 1994, the NSS published The Singapore Red Data Book. The publication became an indispensable source of reference for conservation plans and efforts in Singapore, complementing the global list of threatened species maintained by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.40 To reflect the significant changes in Singapore’s landscape and new conservation locales, the book was updated in 2008 as a joint project of the NSS, NParks, the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (known as the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum since 2015) and the Tropical Marine Science Institute.41

The NSS’ first success at convincing the government to preserve an area for nature conservation is the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve.42 It was opened as a nature park in 1993, then gazetted as a nature reserve in 2002 before becoming Singapore’s first ASEAN Heritage Park the following year.43

The Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve opened as a nature park in 1993, was gazetted as a nature reserve in 2002 and became Singapore's first ASEAN Heritage Park in 2003. One of the migratory birds found at the reserve every year between August and April is the common redshank, which originates from Mongolia, the Russian Far East and China. The bird’s distinguishing feature is its long bright orange-red legs. Courtesy of Mendis Tan, NParks.

The Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve opened as a nature park in 1993, was gazetted as a nature reserve in 2002 and became Singapore's first ASEAN Heritage Park in 2003. One of the migratory birds found at the reserve every year between August and April is the common redshank, which originates from Mongolia, the Russian Far East and China. The bird’s distinguishing feature is its long bright orange-red legs. Courtesy of Mendis Tan, NParks.

Another success story is the preservation of the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) Railway land as a green corridor for flora and fauna to thrive as well as a recreation area for the public. Prior to the closure of the KTM Railway, NSS submitted a proposal to the government, The Green Corridor: A Proposal to Keep the Railway Lands as a Continuous Green Corridor, explaining that the railway track runs through the heart of Singapore and serves as a continuous green corridor connecting many green spaces together. The green corridor is also a potential contender as a future World Heritage Site.44

After the last train pulled out of Tanjong Pagar Railway Station on 30 June 2011 and the closure of the railway the following day, the Singapore Land Authority took over the stewardship of the land and worked closely with the NSS Green Corridor Watch Group. The latter had been formed as a volunteer service to patrol the entire corridor, reporting issues such as overgrowth, fallen trees and illegal encroachment.45

However, not all appeals to the government for areas to be conserved have been successful. In May 1992, the society had asked the government to reconsider filling up the duck ponds at the reclaimed Marina South area as these ponds had become breeding and feeding grounds for several bird species. The Ministry of Environment rejected the request, citing the area as “man-made” and that it might become a public health hazard due to rampant mosquito-breeding in the waterlogged environment.46

Similarly, in 1994, an appeal to conserve land at Senoko in Sembawang as a nature park was rejected by the Ministry of National Development. A working group convened by the ministry, comprising representatives from both the public and private sectors, had weighed various options before deciding not to conserve the site.47

Today, the society continues to promote nature awareness and nature appreciation, and to advocate the conservation of Singapore’s natural environment.

Human Versus Nature

Just like any complex and multilayered ecosystem, nature conservation requires the combined efforts of stakeholders at all levels in order to undertake and manage conservation efforts in a sustainable way.

As NParks works towards making Singapore a “City in Nature”, non-governmental organisations such as the NSS, interested individuals and even the ordinary man in the street also play key roles in educating, creating awareness and seeking cooperation among all Singaporeans in the preservation of our biodiversity and natural heritage. Policymakers and conservationists have to continually work closely together in order to find a middle ground that will enable Singapore to preserve its biodiversity and, at the same time, plan for its future requirements.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the National Library’s collections, developing content as well as providing reference and research services.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the National Library’s collections, developing content as well as providing reference and research services.

NOTES

-

Hariz Baharudin. (2019, May 25). NParks discovers 40 potentially new species of animals in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. (2019, May 25). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Tan, A. (2020, September 26). Go wild over 20 new animal species on Pulau Ubin. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2019, May 20). Conserving our biodiversity: Singapore’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Retrieved from NParks website; Tan, A. (2020, October 25). Development works in Singapore to be more sensitive to wildlife under changes to EIA framework. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Engineered biophysical landscapes: Parks and open spaces for recreation (p. 37). (2004). In Teo, P., et al. Changing landscapes of Singapore (pp. 34–49). Singapore: McGraw-Hill. (Call no.: RSING 333.7315095957 CHA) ↩

-

Gillis, K., & Tan, K. (2006). The book of Singapore’s firsts (p. 96). Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 GIL) ↩

-

Luz, S., & Ramani, V. (2016, September 30). Protecting diversity in Singapore and Southeast Asia. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, J. (2021, February 1). S’pore must balance stewardship of green spaces with land constraints: Desmond Lee. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Tan, M.B.N., & Tan, H.T.W. (2013). The laws relating to biodiversity in Singapore (p. 7). Singapore: Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore. Retrieved from NUS Libraries website. ↩

-

Shorthand report of the Legislative Council. (1884, May 14). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Heng, L.L. (1991, December). Wildlife protection laws in Singapore. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 287–319, p. 294. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Chin, S.-C. (2008). Biodiversity conservation in Singapore. BGjournal, 5 (2), 11–14, p. 11. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The forests in the Straits Settlements. (1883, September 14). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; National Parks Board. (2020, April). History of biodiverstiy conservation in Singapore. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Heng, Dec 1991, p. 295. ↩

-

Singapore forests. (1926, April 28). The Singapore Free Press, p. 262. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Forest reserves in Singapore. (1931, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Davison, G.W.H., & Chew, P.T. (2019, May 29). Historical review of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Singapore. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore, 71 (Suppl. 1), 19–40, p. 25. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Forest reserves to go. (1937, April 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Heng, Dec 1991, p. 295; Forest patrols check illicit felling. (1939, July 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fewer timber thefts at Bukit Timah Reserve. (1939, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Need for preserving S’pore’s flora urged. (1947, May 22). Morning Tribune, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Holttum, R.E. (1951, February 15). Fascinating life among the mangroves. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Extension of nature reserves. (1951, January 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Heng, Dec 1991, p. 296. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2020, April). Nature areas & nature reserves. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2020, April). Mission and history. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Singapore. The statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (2012 Rev. ed.). National Parks Board Act (Cap. 198A). Retrieved from Singapore Statutes Online website. ↩

-

Tan & Tan, 2013, p. 45; Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Secretariat. (n.d.). List of contracting parties. Retrieved from CITES website. ↩

-

Singapore to sign CITES treaty. (1984, November 30). The Business Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Moiz, A. (1993). The Singapore Green Plan: Action programmes (p. 10). Singapore: Times Editions Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 363.7095957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of the Environment. (1992). The Singapore Green Plan: Towards a model green city (p. 1). Singapore: SNP Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 363.7095957 SIN); Moiz, 1993, p. 49. ↩

-

Foo, S.L. (Ed.). (2006). The Singapore Green Plan 2012 (p. 14). Singapore: Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources. (Call no.: RSING q363.70095957 SIN) ↩

-

Chua, L.H. (2002). The Singapore Green Plan 2012: Beyond clean and green towards environmental sustainability (p. 7). Singapore: Ministry of the Environment. (Call no.: RSING q363.70095957 CHU) ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2021). Principles of Singapore’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2019). Conserving our biodiversity: Singapore’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2021). Nature Conservation Masterplan. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Tan, A. (2021, February 11). Singapore Green Plan 2030 outlines many existing initiatives, some new ones worth watching. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Ang, H.M., & Mohan, M. (2021, February 10). Singapore unveils Green Plan 2030, outlines green targets for next 10 years. CNA. Retrieved from CNA website. ↩

-

Nature Society (Singapore). (2020). History of Nature Society (Singapore). Retrieved from Nature Society (Singapore) website. ↩

-

Blaustein, R. (2013). Urban biodiversity gains new converts: Cities around the world are conserving species and restoring habitat. Bioscience, 63 (2), 72–77, p. 75. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Wee, Y.C., & Hale, R. (2008, August 26). The Nature Society (Singapore) and the struggle to conserve Singapore’s nature areas. Nature in Singapore, 1, 41–49, p. 42. Retrieved from Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum website. ↩

-

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of plant and animal species. It uses a set of quantitative criteria to evaluate the extinction risk of thousands of species. The list is recognised as the most authoritative guide on the status of biological diversity. ↩

-

Davison, G.W.H., Ng, P.K.L., & Ho, H.C. (Eds.). (2008). The Singapore red data book: Threatened plants & animals of Singapore (p. iv). Singapore: Nature Society. (Call no.: RSING 591.68095957 SIN) ↩

-

Lee, S.H. (1987, December 14). Bird lovers submit proposals for 300-ha nature reserve. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2020, April). Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Nature Society (Singapore). (2010). The Green Corridor: A proposal to keep the railway lands as a continuous green corridor; Nature Society (Singapore). (2021). Green Corridor Watch. Retrieved from Nature Society (Singapore) website. ↩

-

Zakir Hussain. (2011, July 1). End of an era at Tanjong Pagar. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Nature Society (Singapore), 2021. ↩

-

Kong, L., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (1996). Social constructions of nature in urban Singapore. Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 34 (2), 402–423, p. 409. Retrieved from J-Stage website. ↩

-

Nathan, D. (1994, November 6). Ministry rejects appeal to save Senoko bird habitat. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩