Carving Cultural Imprints: The Hui'an in Singapore

A group of contractors from Hui’an county in China were responsible for building some of Singapore’s iconic landmarks. Athanasios Tsakonas has the story.

In the heart of Geylang, along a nondescript lane inhabited by an assortment of clan associations, guild houses and Chinese temples, an unusual, grey-stone-clad boundary wall greets the casual observer. This masonry “canvas” is adorned with striking sculptured reliefs of what appears to be a bygone period out of China.

Upon closer observation, the artwork reveals a carefully choreographed narrative presenting the cultural identity of the occupants of the premises behind, the Singapore Hui An Association (新加坡惠安公会). A Hokkien (Fujian) clan association that traces its origins to 1924,1 its present members are descended from immigrants who hailed from Hui’an, a county today under the jurisdiction of Quanzhou in China’s Fujian province.

Taking centre stage on this wall is an image depicting a flotilla of traditional tri-masted Fujian junks with a radiating sun in the background (see above). The foreground depicts a man and woman grappling with a woven basket brimming with fish. Occupying the full height of the wall, the scene symbolises the virtue of honest toil that marks the seafaring people of Hui’an who have enjoyed a deep connection with the sea for centuries and prospered from it. It also evokes the trading activity that occurred in the port city of Quanzhou, one of the starting points of the historic maritime silk route. A close examination of the relief reveals a more detailed history and narrative of the Hui’an people.

To the immediate left of the central image of the man and woman is an oblique representation of a multi-pier stone bridge, upon which stands a formally garbed official. This is Luoyang Bridge (洛阳桥),2 recognised as one of the four ancient bridges in China, and the man on it is its designer and builder, Cai Xiang (蔡襄, 1012–67), chief of Quanzhou prefecture, who was also a renowned calligrapher, structural engineer and poet. Spanning 1,200 metres, with 46 ship-shaped piers supporting its stone structure, the Luoyang Bridge’s raft foundations were reinforced through the innovative breeding of oysters alongside, whose liquid secretion aided the binding of the footstones and thus solidified its base.

This bridge is significant as it is believed to be the first stone beam bridge constructed in China using a living organism to reinforce its structure. Further along the full span of this boundary wall, other structures are prominently depicted such as Mengjia Qingshan Temple (艋舺青山宮) in Wanhua District in Taipei,3 the Jingfeng Temple (净峰寺) and Chongwu ancient city wall (崇武城墙) in Hui’an,4 a mosque in Baiqi Xiang (百崎乡) in Hui’an, and a scene of Hui’an women constructing a dam.

Other buildings featured on the wall include the East Hui’an Overseas Chinese Hospital (惠安县惠东华侨医院) and Fujian Hui’an Kai Cheng Vocational Secondary School (福建惠安开成职业中专学校), both of which were constructed thanks to donations by Hui’an philanthropists from Singapore.5

Unveiled on 17 November 2012, this wall measuring almost 12 metres by 1.8 metres was the culmination of an endeavour that had commenced over a year before. It had become apparent to the association’s leaders that there was a growing disconnect between their efforts to sustain the traditions and ancestral links to the “homeland”, and the younger generation who are born and bred in Singapore.

The committee decided that an expression of the key elements of the Hui’an identity could be transposed onto a physical wall fronting their premises. This would provide both a reminder and introduction to the rich history of the Hui’an community, reinforcing their roots and cultural identity in China and throughout the overseas diaspora.6

Given that stone carving in Hui’an has a history of over 1,600 years and is listed as one of the national intangible cultural heritages of China, the committee agreed to engage a sculptor from Hui’an and use granite from the county to create this relief. Tellingly, it was then left to the appointed sculptor, Wang Xiangrong (王向荣), himself a fifth-generation artist and stone mason, to propose the key elements to the diorama.7

In all, the carvings on the wall show how the building and construction industry was instrumental in shaping and moulding the identity of the Hui’an craftsmen who came to Singapore in search of greener pastures.

Arrival of the Hui’an People

Located along China’s southeastern coast of Fujian province, between Quanzhou and Meizhou Bay, Hui’an has come under different administrative jurisdictions throughout its history. During the Sui dynasty (581–618), Hui’an belonged to Nan’an county. In the ensuing Tang dynasty (618–907), it was handed over to Jinjiang county. In 981, Hui’an separated from Jinjiang and established itself as a separate county, before merging with Jinjiang, Tong’an, Nan’an and Anxi into the modern-day prefecture-level city of Quanzhou.

Whereas Quanzhou was connected to the internal China hinterland through its early trade networks, it was during the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties that this city would become an important centre for international commerce, which also facilitated extensive contact with foreign cultures and merchants. To promote trade, Quanzhou’s internal infrastructure was greatly improved with roads, bridges and associated works.

This construction programme not only necessitated a great investment by the authorities but also brought with it the need for large numbers of highly qualified architects, engineers and tradespeople. At the same time, on account of Hui’an’s vast repositories of granite, the stone industry flourished, with thousands of masons involved in stone-cutting and carving for such public utilities as gateways, sanctuaries and pagodas.8

Thanks to Quanzhou’s deep-sea port, established trade routes and the overseas networks created by the Chinese diaspora, these stone commodities would subsequently find their way to and across Southeast Asia. According to Claudine Salmon and Myra Sidharta in their essay, “The Manufacture of Chinese Gravestones in Indonesia”, it was the need for ballast on the sailing ships that provided the economic case for transporting stone from Hui’an to Southeast Asia. Both plentiful and inexpensive, these stone ballasts (壓船石; yachuan shi; literally “stones that keep the ship down”) would be exchanged along the journey’s various ports with an equivalent weight in commodities and goods for the return leg.9

Both raw stone and carved slabs for tombstones, graves and temples also made their way across the South China Sea, bringing not only the products but also stamping the reputation of the Hui’an people for their quality material and workmanship. It was a prelude to the human capital that eventually arrived in the region in general and, Singapore in particular.

Following the arrival of Stamford Raffles in 1819 and the establishment of a British trading port thereafter, the early Chinese migration to Singapore was predominantly drawn from the Straits areas and southern China.10 Significant migration from Quanzhou would only commence from the late 19th through to the beginning of the 20th centuries.

Arriving later, along with migrant groups from Fuzhou, Putian and Fuqing, the people from Hui’an would find that what profitable industries were available in Singapore had already been taken up by others so they initially settled as coolies (indentured labourers)11 doing back-breaking work. Those who came from coastal northern Hui’an and were accustomed to the sea and fishing, made their home on large bumboats by the Singapore, Rochor and Kallang rivers, navigating between them and the coast for their livelihoods.12 Others worked as rickshaw pullers or as labourers in the construction, mining and agriculture sectors in exchange for three meals a day.

Before the Hui An Association was founded in Singapore in 1924, early Hui’an immigrants sought out and received help from their fellow clansmen who had arrived before them. Their most pressing needs were finding accommodation and employment. Most lived in shophouses in the Tanjong Pagar area comprising Craig Road, Tras Street, Duxton Hill and Duxton Road in lodgings known colloquially as coolie keng (估里间; gu li jian). Here, dozens of men would be crammed into tiny, compartmentalised and windowless rooms – most without running water or proper sanitation – sleeping on tiered wooden bunk beds that were also shared. Despite the deplorable living conditions, these lodgings kept the new migrants together and afforded them some form of protection.

Faced with isolation, alliances between fellow Hui’an men would form, mostly through membership in secret societies or triad associations. In the case of the Craig Road and Duxton Hill areas, where the Hui’an migrants worked mainly as rickshaw pullers, membership was allied under the surnames of Ho, Chang and Chuang.13

For those Hui’an migrants with masonry or carpentry skills or who had valuable trade experience back home, Singapore’s buoyant building and construction industry provided them with a myriad of opportunities. They began as subcontractors to more established entities before expanding their operations and becoming main contractors, inevitably encroaching into the domain of established European contractors.14

Many European firms took advantage of this situation by subcontracting to these Chinese companies. In many cases, the European firms would retain their names as principal contractors and supervise the work through their appointed resident engineers. In light of Japan’s growing military might, the British authorities saw the need to further strengthen Singapore’s defences, with opportunities arising in building as well as upgrading new and existing military camps and associated defence facilities. In turn, this productive period in building and construction work would help to elevate the reputation of these pioneering Hui’an contractors in Singapore.

Notable Hui’an Contractors

Soh Mah Eng

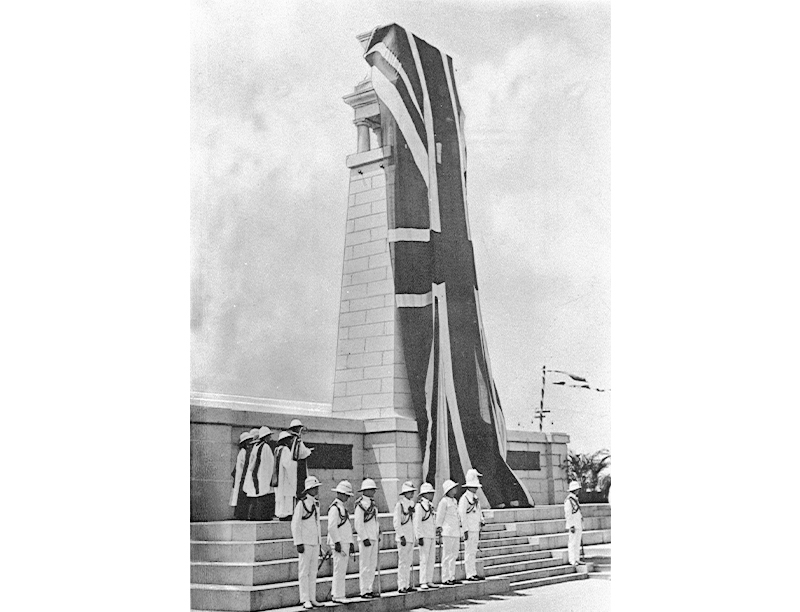

Alighting from his car on 31 March 1922 to the backdrop of curious onlookers at the Esplanade (now Padang) and a guard of honour consisting of 100 former servicemen, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) inspected this ceremonial guard before making his way to the foot of the war memorial, which was erected to honour 124 men from Singapore who had died in action in Europe during World War I. Delivering a speech extolling the virtues of bravery and sacrifice displayed by those men being commemorated, he proceeded to push a small button on the dais. With that action, a large Union Jack, fully draped over the structure, pulled away to reveal the new Cenotaph.15

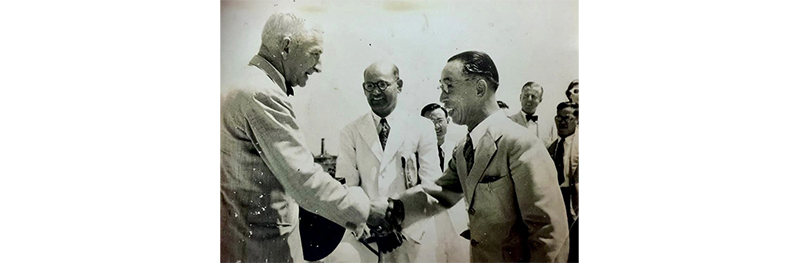

Following a short dedication by the Bishop of Singapore and the sounding of the last post and reveille, the prince, accompanied by Governor of the Straits Settlements Laurence Guillemard, greeted the invited dignitaries, which included the monument’s lauded architect Denis Santry of architectural firm Swan & Maclaren. Among that gathered company of Singapore’s building fraternity was Soh Mah Eng (苏马英), the contractor for the monument. The prince cordially shook his hand and even offered a few words of gratitude.16 It was fitting recognition for this Hui’an native who had migrated to Singapore some 20 years earlier and subsequently through his company, Chin Hup Heng & Co., became a pioneer in the island’s infrastructure development.

Modelled after the Whitehall Cenotaph in London, the 18-metre-tall Singapore Cenotaph, raised on a plinth, would be entirely constructed of local granite. Bronze tablets inscribed with the names of the fallen adorn its face.17 Given its national significance, the quality of its finish was expected to be of the highest standard. The British colonial government, well aware of Hui’an’s reputation with stone and already familiar with Soh’s earlier work on Anderson Bridge, appointed him as the builder to undertake the main building works.

Finding himself short of manpower soon after commencing, Soh appealed to the authorities for additional labour and was allowed to recruit more than 200 skilled masons from his hometown village of Sukeng in Hui’an.18 The Cenotaph was thus successfully completed on schedule. What is more significant, though, is that the memorial helped cement the Hui’an community’s reputation for construction work in Singapore and provided the island with a future generation of skilled stone craftsmen as well.

Before long, fellow Hui’an natives such as Chia Eng Say, Chia Lay Phor, Ho Bock Kee, Zhuang Yuming, Lee Chwee Kim, Chng Gim Huat and Ong Chwee Kow to name but a few, would follow in Soh’s footsteps and make a name for themselves. These men would be responsible for some of the most significant landmarks in Singapore and Malaya. Furthermore they did not confine themselves to the construction industry, soon diversifying into industries such as quarrying, rubber, tin mining, steel, trading and development.

Chia Eng Say

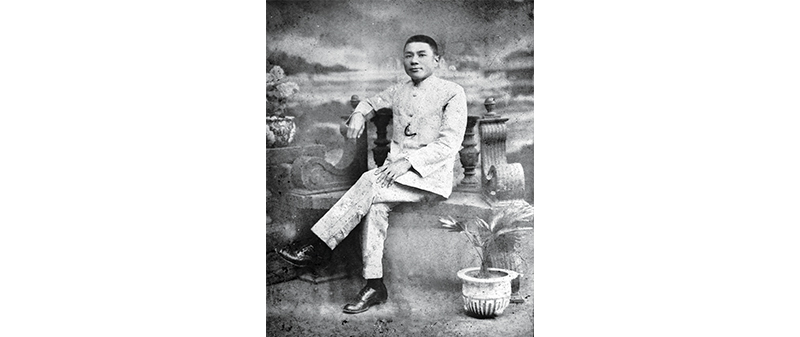

Among the most prominent in this group is Chia Eng Say (谢荣西). Born in 1881 in Hui’an, Chia first moved with his father to Sumatra at the age of 11 and then to Singapore at the turn of the 20th century. He initially established himself in the import-export business before moving into construction and, in particular, the stone industry.

Chia owned several quarries in Bukit Timah, Mandai and Pulau Ubin. Granite extracted from Chia Eng Say Granite was used for the foundation of the Supreme Court building, the Naval Base at Sembawang as well as the Causeway, where he was a major subcontractor to Messrs Topham, Jones & Railton of London, which had been awarded the construction contract.19

Other notable projects to his name include the China Building (which became the headquarters of the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation after the merger of the Oversea-Chinese Bank and the Chinese Commercial Bank in 1932) on Chulia Street,20 along with numerous schools and private residential estates in both Singapore and Penang. Such was his prominence within the local construction industry that the track in Bukit Timah upon which his quarry was located would be named Chia Eng Say Road. (This road was later expunged but the name was subsequently resurrected; today Chia Eng Say Road lives on in Upper Bukit Timah, just fronting The Rail Mall.21)

It was in education that Chia would make his most important contribution. In 1929, he was appointed as the main contractor for the Chinese Industrial and Commercial Continuation School (南洋工商补习学校) on Outram Road at York Hill.22 A decade later, Chia would join with fellow philanthropists to build Chung Cheng High School on Kim Yan Road in 1939,23 making it one of the largest schools in Singapore and Malaya at the time. Sadly, on the final day of the Imperial Japanese Army’s invasion of Singapore in February 1942, Chia would be caught in a crossfire between Japanese and Australian troops along Geylang Lorong 31 and mortally wounded.24

Chia Lay Phor

Whereas Soh Mah Eng and Chia Eng Say arrived as children in Singapore and learnt their trade through their fathers, the same could not be said of Chia Lay Phor (谢荔圃), the nephew of Chia Eng Say. Hailing from the western Hui’an town of Huangtangzhen, Chia came from a well-to-do family where his grandfather owned a cloth dyeing business. This enabled him to be one of the privileged few in Hui’an to have received an education and be trained as a teacher. Although most Hui’an males emigrated because of the poverty and lack of opportunities back home, Chia’s motive differed markedly.

Unfortunately, Chia’s ability to write letters and maintain accounts also became the source of his problems: he had been kidnapped twice by bandits who wanted him to work for them. Needless to say, this was not a tenable proposition so he migrated to Singapore as a 24-year-old. He immediately went to work at Chia Eng Say’s construction company, Chia Eng Kee Chan, rising to the post of general manager and overseeing projects in Malaya and Singapore.25

Eventually branching off, he became a contractor for the Public Works Department. The younger Chia’s added engineering skills saw him involved in numerous heavy infrastructure projects for the British authorities. These include the levelling of Kampong Silat Hill for the Singapore Improvement Trust’s housing development scheme in 1948, and the new taxiways and extension of the runway at Kallang Airport a year later. His most significant accomplishment, though, and that which accorded him the most professional recognition within the industry occurred just prior to World War II.

Between 1937 and 1940, while still working for his uncle, Chia Lay Phor oversaw his largest and most extensive construction project: building the 356-bed British Military Hospital (now Alexandra Hospital). Chia Eng Kee Chan had been appointed as the main subcontractor for Dobb & Co. and the War Department. The hospital was equipped with medical, surgical and officer wards as well as ancillary buildings comprising a barracks block, a laboratory, a mortuary and living quarters for staff and their families.26

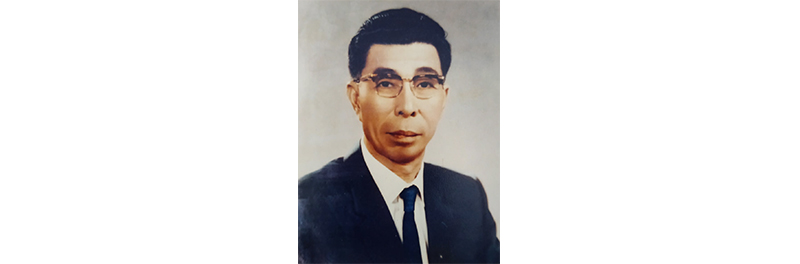

Ho Bock Kee

Born in 1905 in the small village of Fengqi in Wangchuan town in Hui’an county, Ho Bock Kee (何穆基) was the eldest of four children. His father was a carpenter while his mother was a housewife. Although daily life in a small rural community was hard and poverty was an everyday reality, his early exposure to carpentry and Hui’an’s economy centred around construction would prove invaluable. Unlike the impoverished and unskilled Chinese immigrants who ended up as indentured labour in Southeast Asia, Ho arrived in Singapore in 1929 as a qualified carpenter.

Initially subcontracting his labour to other builders working on numerous army camps and military facilities across the island, the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) saw Ho resorting to slipping in and out of Malaya undertaking odd jobs to survive. It was the post-war demand for reconstruction that provided him with the impetus and opportunity to venture into main contracting.

Capitalising on the opportunity, Ho established his own construction company – beginning where he left off before the war – repairing and rebuilding old army camps and bases as well as those used for internment. An invaluable listing on the preferred contractor panel for the Public Works Department soon followed, and over the next 30 years, Ho Bock Kee Construction was awarded numerous public and private contracts, including a Ngee Ann Kongsi school on Balestier Road (1965), Singapore Television Studio Centre at Caldecott Hill (1966), Bedok Reformative Training Centre (1961), Mount Vernon Crematorium (1962) and the National Library building on Stamford Road (1960).

As a main contractor, Ho’s most internationally recognised work was the Singapore Memorial at the Kranji War Cemetery. Officially unveiled on 2 March 1957 by the Singapore Governor Robert Black and attending international dignitaries, the event was broadcast throughout the Commonwealth to an extensive overseas audience.27 Designed by the British architect Colin St Clair Oakes, the memorial was built to resemble an aeroplane with its 22-metre central pylon and wing-shaped roof supported by 12 stone-clad pillars.28 The names of over 24,000 casualties without known graves are inscribed on the pillars. Memorial services are held at the cemetery every year on Remembrance Day (11 November), as well as ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Day on 25 April.

Leaving a Legacy

By the late 1980s, the Hui’an construction community in Singapore accounted for almost 50 enterprises, excluding those in the region. By now, the Hui An Association had expanded to include representation throughout most of Malaysia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia and greater China. These pan-Asian cultural ties led to further opportunities for a new generation of industry pioneers.

This story of the enterprising and intrepid Hui’an people and their contributions both within and outside China is an inspiring one. It was with this in mind that the sculptured wall fronting the Singapore Hui An Association at Lorong 29 Geylang was commissioned. It is both an icon of the success that Hui’an immigrants have achieved overseas as well as an enduring symbol of their contributions to the Chinese homeland – as evidenced by depictions of the aforementioned Fujian Hui’an Kai Cheng Vocational Secondary School and East Hui’an Overseas Chinese Hospital.

The images carved on the stone wall and the memories they recall of the homeland also serve another purpose, as captured by the Greek word nostos, which means “homecoming”. In ancient Greek literature, it describes an epic hero returning home by sea. The term − first recounted in Homer’s The Odyssey − refers not merely to the physical return of the hero but to his elevated identity and status upon arriving home. In a similar way, the Hui’an stone frieze depicts the journey of an enlightened culture to Southeast Asia and its eventual return back home.

His book, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial, was published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in 2020. Containing photographs, maps and architectural plans, the publication draws on extensive archival research and interviews conducted in Europe, Australia and Asia.

His book, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial, was published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in 2020. Containing photographs, maps and architectural plans, the publication draws on extensive archival research and interviews conducted in Europe, Australia and Asia.The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 725.94095957 TSA and RSING 725.94095957 TSA). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Athanasios Tsakonas is a practising architect with degrees from the University of Adelaide and National University of Singapore. His book, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial, was published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in 2020. He is currently based in Melbourne, Australia.

Athanasios Tsakonas is a practising architect with degrees from the University of Adelaide and National University of Singapore. His book, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial, was published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in 2020. He is currently based in Melbourne, Australia.

NOTES

-

Established in 1924 as the Singapore Hui Ann Association, for the purposes of this essay the toponymic reference will instead be either the hanyu pinyin pronoun “Hui An” or the noun “Hui’an”. ↩

-

Situated at the mouth of the Luoyang River, the Luoyang Bridge (also known as Wan’an Bridge) in Quanzhou was constructed between 1053 and 1059 in the Northern Song dynasty. In 2021, the bridge was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. ↩

-

The Mengjia Qingshan Temple is dedicated to Qing Shan Ling An Zun, a general from Hui’an, Quanzhou. ↩

-

Chongwu town is located in southeastern Hui’an. The town’s historical centre, the Old Chongwu Fortress, is a walled city dating back to the late 14th century. ↩

-

The Fujian Hui’an Kai Cheng Vocational Secondary School building was gifted to Hui’an by Ong Chwee Kow, a successful contractor and developer. The school imparts trade skills to young men and women without the means and opportunities. The East Hui’an Overseas Chinese Hospital building was gifted to the county by the steel magnate Liu Mah Choon, which superceded his earlier donation of a dispensary on the same site. ↩

-

Joseph Chia, online conversations, 20 February 2019 to 17 August 2021. ↩

-

“故乡的石头会说话: 惠安公会石雕壁画展风情” [“Hometown’s Stones Can Talk: Hui’an Guild’s Stone Sculpture Murals Exhibition Style”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 24 February 2013, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Claudine Salmon and Myra Sidharta, “The Manufacture of Chinese Gravestones in Indonesia – A Preliminary Survey”. Archipel 72 (2006): 196, https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_2006_num_72_1_4031. ↩

-

Salmon and Sidharta, “The Manufacture of Chinese Gravestones in Indonesia,” 198–99. ↩

-

While the earlier Chinese migrants were mainly from the Cantonese and Hokkien dialect groups, those from Hui’an spoke either the Xinghua or Minnan dialect. ↩

-

The word “coolie” is believed to have originated from the Hindi term kuli, which is the name of a native tribe in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The word kuli also means “hire” in Tamil. See Naidu Ratnala Thulaja, “Chinese coolies,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

Otherwise known as twakow or tongkang, the bumboat was a large barge vessel used extensively for transport purposes along the Singapore, Rochor and Kallang rivers, and also along the coast of the mainland and other nearby islands. See Vernon Cornelius-Takahama, “Bumboats,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published June 2019. ↩

-

“Coolie Keng and Their Alliances,” Straits Times, 31 August 1982, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“European Contractor Gives Evidence in Loveday Case,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 22 August 1940, 5. (From NewspaperSG). Many of these practices came to light during the 1940 trial by court martial of Captain R.C. Loveday, R.E., who was charged with conspiracy to defraud the War Department. ↩

-

“At the War Memorial,” Malaya Tribune, 31 March 1922, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zaubidah Mohamed and Valerie Chew, “Cenotaph,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2010. ↩

-

区如柏 [Ou Rubo], “不做拉车夫走入建筑界的惠安人” [“Rickshaw Drivers No Longer, the Hui’an People Enter the Construction Industry”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 25 December 1988, 34. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 5 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 2 August 1939, 5; “Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 14 February 1938, 6. (From NewspaperSG); 中正中学校友会, 源远流长: 中正中学创校八十周年纪念文集 = A Chung Cheng 80th Anniversary Commemorative Publication, Chung Cheng High School Alumni 2019 (Singapore: 中正中学校友会, 2019), 44. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Chinese RSING C810.08) ↩

-

Completed in 1932, the five-storey China Building was one of the most recognisable landmarks in the business district with its distinctive pagoda-stye roof. It was designed by international architectural firm Keys and Dowdeswell, which operated out of Shanghai, China. The firm was named after British architects Major P. Hubert Keys and Frank Dowdeswell. See “New Bank Building,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 July 1929, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Located near the former Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) Railway truss bridge along Upper Bukit Timah Road, Chia Eng Say Quarry is now a lake known as Singapore Quarry within Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Chia Eng Say Road, which ran parallel to the KTM Railway line, was a private road built by the quarry company to gain access to their quarrying operations. The road also ran through a Chinese kampong called Kampong Chia Eng Say. See 柯木林 [Ke Mulin; Kua Bak Lim], “敢问路在何方?” [“Who Dares to Ask Where the Road Is?”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 18 August 2012, 20. (From NewspaperSG); Victor R. Savage and Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2013), 74. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 915.9570014 SAV-[TRA]) ↩

-

Established in1920 by Mr Shi Su, the Chinese Industrial and Commercial Continuation School started out as an evening Chinese school for working adults on Tanjong Pagar Road. It moved to Enggor Street in 1920 and then to York Hill in 1929. The school closed in 1985 and reopened as Gongshang Primary School, currently located in Tampines. See also “工商補習學校建校募捐之第一日,” 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 21 February 1929, 4. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

The first principal of Chung Cheng High School was Chuang Chu Lin (庄竹林; Zhuang Zhulin) (1930–57), who was also a Hui’an native. The school moved to larger premises on Goodman Road in 1947 and was renamed Chung Cheng High School (Main). The original campus on Kim Yan Road became Chung Cheng High School (Branch) and has since moved to Yishun. ↩

-

莫美颜 [Mo Meiyan], “若有来世还要做他女儿 庄曼娜忆父亲庄竹林” [“If There is an Afterlife She Will Still Want to be His Daughter, Zhuang Manna Recalls Her Father Zhuang Zhulin”], 新加坡新闻头条, 5 February 2020, https://toutiaosg.com/若有来世还要做他女儿——庄曼娜忆. ↩

-

Joseph Chia, online conversations, 25 June 2021. ↩

-

“Big Singapore Military Hospital,” Straits Times, 7 August 1938, 17; “New Singapore Military Hospital,” Straits Times, 29 January 1939, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Athanasios Tsakonas, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2020), 184–86. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 725.94095957 TSA) ↩

-

Colin St Clair Oakes also designed Kanchanaburi War Cemetery and Chungkai War Cemetery, both in Thailand; Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma; Imphal War Cemetery in India; Sai Wan Bay Cemetery in Hong Kong; and Chittagong War Cemetery in Bangladesh. See Athanasios Tsakonas, “In Honour of War Heroes: The Legacy of Colin St Clair Oakes,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 3 (Oct–Dec 2018). ↩