The Modern Girls of Pre-war Singapore

Andrea Kee explores how the enigmatic Modern Girl asserted her new-found identity, femininity and independence in interwar Singapore.

In the first half of the 20th century, major cities around the world began to witness a new phenomenon: the emergence of the Modern Girl.1 She was almost instantly recognisable with her distinctive wavy bobbed hair, painted lips, slim body (often with her arms and back exposed), and always impeccably dressed in the latest fashion.2 A historically specific expression of modernity and femininity, she appeared almost simultaneously in cities like Beijing, Bombay, Tokyo and New York during the interwar years.

The Modern Girl was also a phenomenon in Singapore of course. As diplomat-turned-writer R.H. Bruce Lockhart noted in his memoirs, women here – particularly Straits Chinese women – had changed significantly by 1933 compared with the early 1900s. “Gone, too, is the former seclusion of the better-class Chinese women, and to-day Chinese girls, […] all with bobbed and permanently waved hair in place of the former glossy straightness, and all dressed in semi-European fashion, walk vigorously through the streets on their way to their studies or to their games.”3

Departing from the traditional female roles of “dutiful daughter, wife and mother”,4 women were becoming increasingly involved in activities such as working, sports, and smoking and drinking, which were previously considered the domains of men.5 These social changes were in part motivated by the rise of feminism, the development of women’s suffrage movements in places like Britain, America and India, and more women participating in nationalist movements.6

According to the Modern Girl Around the World Research Group based in the University of Washington, American corporations were “the most important international distributor of imagery associated with the Modern Girl, especially because of US pre-eminence in the international distribution of advertising and film”.7 Hence, the image of the Modern Girl, and her associated iconology and ideologies, found their way across the globe through the worldwide channels of multinational corporations, print media and the American film industry. By the late 1920s, the Modern Girl had made her debut in Singapore.

A Modern Girl By Any Other Name

While the term “Modern Girl” first appeared during the 1920s and 30s, the use of the term “girl” was popularised in England in the late 19th century and referred to “working-class and middle-class unmarried women who occupied an ephemeral free space between childhood and adulthood”. By the 1920s and 30s, however, “girl” had come to refer to young women who aspired to subvert conventional female roles and expectations.8

The Modern Girl went by different names in different places. In the US, she was sometimes known as a “flapper”, in China as 摩登小姐 (modeng xiaojie; modern young lady) and in India as kallege ladki (college girl). In Singapore, the English-language press commonly referred to her as the Modern Girl or Modern Woman. Regardless of what she was called, Modern Girls were identified as young women with an “up-to-date and youthful femininity”, provocative in behaviour and fashion that drew influence from other countries.9

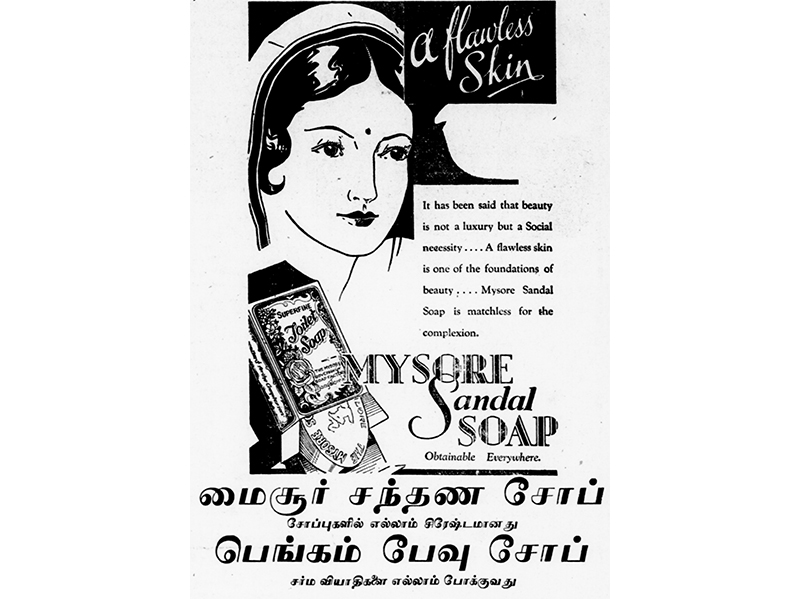

As international companies began customising their advertisements to appeal to domestic markets, local companies started adopting the advertising strategies of international companies.10 By the 1930s, local businesses had begun constructing a Modern Girl relatable to the masses in Singapore. Advertisements in Singapore’s vernacular and other English press targeted at local Asians often featured a female with features drawn from elsewhere, yet sporting elements distinctive to the cultures of the region (such as the muslim headscarves and the coloured dot known as bindi that Indian women wear on their foreheads).

The Modern Girl in Singapore

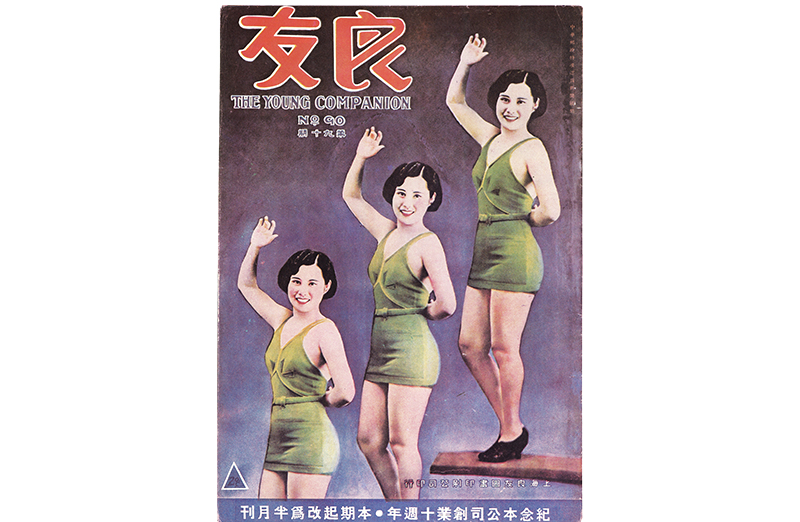

The print media – such as pictorial magazines, journals and newspapers – also began selling a modern lifestyle and culture. In cities like Shanghai, pictorial magazines such as《良友》(Liangyou; The Young Companion), featured the latest in fashion, makeup and celebrities.11 Available in Singapore, Liangyou would have presented a different way for women to see themselves and shape their lives.12

According to historian Chua Ai Lin, Hollywood played a key role in influencing social change among Singapore’s youth and the city’s modern identity. Singapore’s young women looked to Hollywood not only for fashion and beauty tips and trends, but also for contemporary views on love, sex and romance. Chua suggests, however, that cultural products such as film appeared to effect greater change in women due to the parallel evolution of women’s social roles.13

The interwar years in Singapore saw drastic changes in women’s societal roles. For the first time, a significant number of females had become part of the workforce, consumers of public amusements and, more importantly, students.14

A number of factors were at work. First of all, there were simply more women in Singapore. As resistance against female emigration in China eroded, more Chinese women moved to Singapore in search of work.15

Women’s roles in society were also evolving due to changing attitudes towards female education. And as more women received an education, they could now participate in the public sphere, look for paid work, have more opportunities for self-expression and leisure, and engage in various cultural and political movements. They would have also been exposed to more possibilities of modern life through education and various cultural products and, with these, new identities.

Fashioning Singapore’s Modern Girl

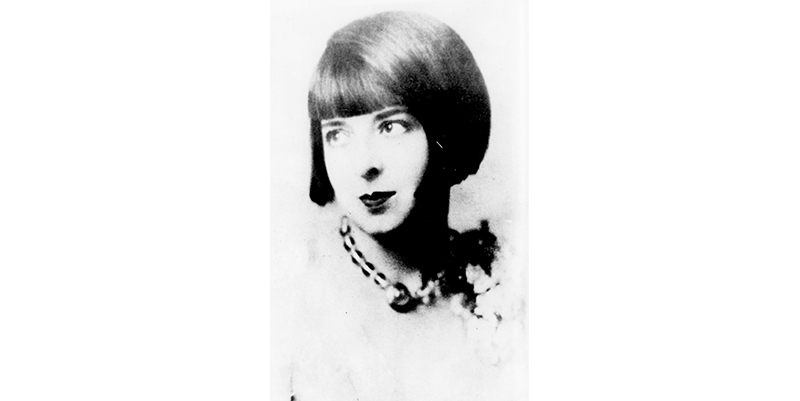

Singapore’s Modern Girl challenged existing gender norms through her expressions of femininity, most visibly through fashion and style. From the 1920s, she adopted Western-style clothing (with short hemlines and high heels), wore makeup and sported a bob haircut.16

One such young woman was Betty Lim, who later wrote A Rose on My Pillow: Recollections of a Nyonya. Before the popularity of the Modern Girl look, her long hair was usually styled in a traditional Straits Chinese sanggul (plaited hair that was coiled up) for formal events. In the late 1920s, Lim cut her hair in the style of American actress Colleen Moore – a straight bob with a fringe – and showed off her new “radical” look at a party she attended with her sibling.17

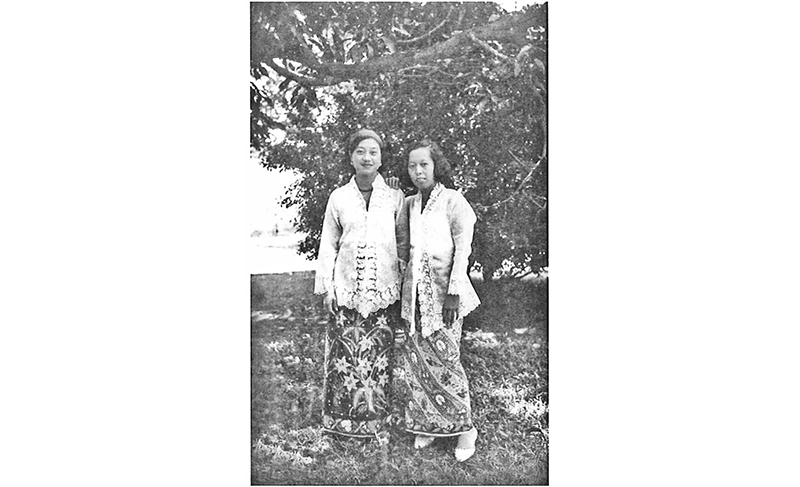

Singapore’s Modern Girls were also influenced by fashion styles from the region, such as the sarong kebaya (a tight-fitting sheer embroidered lace blouse paired with a batik sarong skirt), which was first worn in Java in the Dutch East Indies. In the 18th and late 19th centuries, Peranakan women typically wore the baju panjang or baju kurung (a knee-length tunic worn over a batik sarong), but by the 1920s the sarong kebaya had become the attire of choice for Peranakan women in the Dutch East Indies and younger Peranakan women in the Straits Settlements.18

The cheongsam (or qipao; also known as the Shanghai dress) was also gaining favour among young modern Chinese women in Singapore. Popularised by Shanghai’s film stars, the cheongsam was cut to fit – and flatter – the female figure.19 Prior to this, young, educated Chinese women had worn the sam kun, a long sleeve blouse paired with a calf-length skirt.20 By the 1930s, Straits Chinese women in Singapore had begun to add the cheongsam to their wardrobe staples.

Singapore’s Modern Girls also adopted a hybrid East-meets-West style, combining Western trends, such as wavy bobs and makeup, with local fashions. The quest for modernity expressed through fashion was riddled with anxieties about what constituted the ideal modern feminine aesthetic, especially in a cosmopolitan city where multiple ideas of modernity circulated. The Modern Girl’s fashion and style was therefore not without controversy – she faced criticism for dressing immodestly, overspending on cosmetics and being too “Westernised”.

The press became a space where Singapore’s Modern Girls could push back and make their case, their letters affording a glimpse of how these young, educated and assertive women articulated their own identities and expressions of modernity through their appearance and individuality. One of these platforms was the Malaya Tribune, the most popular English-language newspaper among middle-class anglophone Asians in Singapore and Malaya in the 1930s.21

Those who wrote to the Malaya Tribune were mainly English-educated Straits Chinese men and women, hence when the topic was discussed, it tended to centre on the Chinese Modern Girl. (It is important to note, however, that many letter-writers used pseudonyms, making it a challenge to ascertain their identities and verify the content. Nonetheless, these letters offer valuable insight into the voices of educated Asians in colonial Singapore.)

In March 1931, a “Miss Tow Foo Wah” voiced her concern that her fellow female schoolmates were wearing Western-style dresses that were “much too short above the knees”, describing them as “disgraceful”.22 Similarly, another writer who used the name “Evelyn” expressed that “a skirt that is six inches above the knees or a flear[sic]-skirt with the upper part exposed is a disgrace to put on. […] It is better for us to put on skirts exactly up to the knees or an inch above or lower”.23

In defence, a “Miss Anxious” argued: “If short skirts give comfort as well as add charms to one’s personality, why shouldn’t one wear them? […] As long as it makes us fascinating and fashionably elegant what do we care about what others say?”24

Chinese Modern Girls wearing Western-style attire were often criticised for copying Western trends and being an embarrassment to national pride.25 A Helen Chan and “A Modern Chinese Girl” astutely pointed out that Chinese men, too, wore Western-style clothing but were not subjected to the same judgement.26

Also commonly under fire was the Modern Girl’s use of cosmetics. In his letter to the Malaya Tribune in 1938, a Chia Ah Keow called Modern Girls superficial and criticised their excessive expenditure on cosmetics and beauty products, even providing a list of such products – highlighting ones with questionable names like “Forget-me-not” and “Kiss-me-again” lotions.27

Chia’s letter provoked responses from “A Modern Girl” and a Juliet Loh, who described him as “ridiculous” and “out of his mind”, noting that there were no products with such names. In her letter, Loh pointed out that most Modern Girls in Singapore did not wear makeup,28 one of the key characteristics of the global Modern Girl. Her emphasis on how Singapore’s Modern Girls did not use cosmetics also highlights how to some of the city’s Modern Girls, wearing make-up was not part of their identity even though globally, it was seen as a marker of being one.

The notion of modernity as understood among the locals was not fixed, and some ethnic Chinese might have looked to their cultural heritage for ideas about what the Modern Girl should embody. As a Chinese woman, Loh could have been influenced by the overseas Chinese’s interpretation of modernisation, which drew heavily on Chinese national and ethnic pride and emphasised the importance of retaining traditional representations of “proper” femininity such as not wearing makeup or jewellery.29

Life, Love and Work

Singapore’s Modern Girl also defined her modern identity through her attitude towards life and aspirations for her future. In her letter to the Malaya Tribune, “Evelyn” explained that Modern Girls now had a newfound sense of freedom and could freely go “shopping or to a friend’s house unchaperoned sometimes”, in sharp contrast “to our grandfather’s period [when] it was very hard for a man even to see a girl’s shadow”.30

More and more non-European women in Singapore were educated and becoming more active in public life. The Modern Girl could now choose who to marry and how she wanted to live her life.31 A 1938 Straits Times article reported that modern Chinese youths, particularly those who had been educated at English-medium schools, believed that marriage should be founded on “love and courtship” and thus rejected arranged marriages. They also wanted fewer children and hoped to have their own marital home instead of living with their in-laws.32

Women like “Adelina” also wrote letters to the Malaya Tribune encouraging fellow young women to develop their own outlook on life before getting married, warning that “many girls fall blindly in love with men and settle down before they know really what life is”.33

Thanks to education, Modern Girls were able to break with conservative norms and seek jobs outside the home. The Straits Times reported in 1939 that an increasing number of young Chinese women in Malaya were taking up professions, even “invad[ing] the mercantile offices” and “ousting young men from their positions”. It added that after leaving school, many women furthered their studies by attending classes to study shorthand, typewriting and book-keeping so as to prepare themselves for office careers. Other professions that young Chinese women took up included retail, nursing and teaching.34

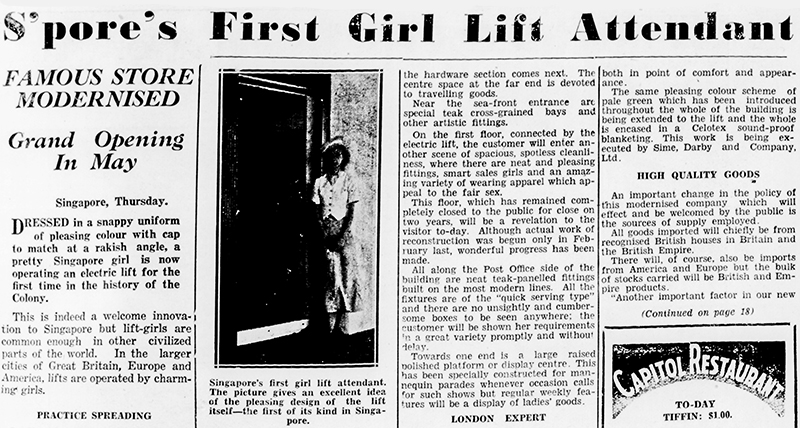

Women also started to break into traditionally male dominated jobs. In May 1936, the Singapore branch of the Whiteaway departmental store opened its newly modernised store. While it boasted new features such as an electric lift, the true marker of its modernity was the introduction of Singapore’s first-ever female lift operator. Whiteaway was praised for following the lead of “other civilised parts of the world” such as Britain, Europe and America and the young lift operator was described as having “courageously given the lead” on the modernisation of the store.35 In another article, the Morning Tribune wrote that in employing a woman to be a lift attendant, Malaya had shown that it accepted the modern principle that “girls are as good as men at some jobs”.36

The Modern Girl’s new outlook on life and work sparked debate among Asian anglophones in the press. In a 1938 opinion piece, Zola, a Malaya Tribune correspondent, mused whether young women should be allowed the right to compete with men for commerce jobs.37

Several readers wrote in to argue that women should not be given the same opportunity because they were “naturally weaker” compared to men. A G.S. Teo claimed that, unlike men, women were incapable of withstanding the “strain and stress” of industrial life. He also saw men and women as playing inherently different roles and incapable of sharing them. He added that if the “future tendency of educated girls is to usurp the ‘bread and butter’ positions of men, we might then envisage a time, when we boys must learn how to cook, sew, look after the homes and the babies!”38

Another reader, C.T.C., argued against women working in “men’s work” because it was not what “Nature has best equipped them to accomplish”. Instead of working in traditionally male spaces, he advised women to develop “talents… peculiar to their sex” such as homemaking, teaching, nursing and dressmaking.39

Many readers challenged such mindsets. “Educated Female” wrote in response to Zola: “Singapore is still trailing behind the times if it harbours such an ignoramus as ‘Zola’ who dares to submit that ‘boys in every way are far more capable of discharging their duties than girls’.”40 Another female reader, Sunny Girl, highlighted that women had every right to use their educational qualifications and independence to secure employment to support their families.41

The Limits of a Modern Girl

Some Modern Girls were able to go well beyond the role that society had prescribed for women. Mrs H.A. Braid, née Lona Soong Tong Neo, was a Modern Girl who, despite her father’s lectures on “how a good daughter should behave”, made life choices that were considered unconventional for her time: she cut her hair short, found employment as a clerk, and even went overseas for work.42

However, conservative ideas were still pervasive even among Modern Girls. For instance, Betty Lim might have looked like a Modern Girl, but she did not share all the ideals of personal agency that they embodied. She led a sheltered life and did not have close contact with men and was, in fact, not allowed to go out with her fiancé unchaperoned.43

Modern Girls had to constantly contend with prevailing patriarchal expectations of becoming wives and mothers, as well as those who were anxious about how such young women challenged “traditional structures of authority”.44

In 1931, a robust discussion on whether Modern Girls were “unmarriageable” unfolded in the Correspondence section of the Malaya Tribune. The debate was sparked by an article about the problem of unmarriageable modern Chinese girls, citing the Modern Girls’ “ultra-modernism, materialism, misinterpretation of life desire for so-called emancipation and freedom” as reasons they would be unable to find willing husbands.45

While some agreed that Modern Girls lacked the ability to manage domestic affairs to “lessen their husbands’ burdens”,46 others sympathised and argued that Modern Girls possessed “the power to lead young men along the right path”, as any good wife would.47 However, both sides ultimately placed the value of Modern Girls on their abilities to be good wives and mothers.

In her Straits Times article, June Lee said that despite the new freedoms enjoyed by the Modern Girl, it was unquestionable that they would eventually have to marry: “[The Modern Girl] may take up a career – an escape from domestic boredom for a while – but her ultimate aim is marriage.”48 Other articles touted the Modern Girl’s increased education as a path that opened up greater career opportunities, but in the same breath also noted it made her an “asset to her husband” by being a better companion. After marriage, many husbands preferred their working wives to stay home to “learn the career of being a ‘helpful wife and wise mother’”.49

Despite modernity’s promise of a more liberated lifestyle for women, not all young women could aspire to be Modern Girls though. Many young women, especially those from poorer families in interwar Singapore, still had limited freedoms and found it difficult to break with conventional gender roles. It was only after the war that more women across different social classes began venturing out of the domestic sphere to work, and attire favoured by the Modern Girl, such as the cheongsam, became more affordable.50

Whatever the case, the Modern Girls of the period played a key role in initiating discourse and debates about the expectations of modern womanhood, and in defining young women’s identities in a world vastly different from that of their mothers’.

Despite the criticisms and limits placed on Modern Girls, they actively, vocally and bravely challenged their detractors to prevent themselves from being seen solely as wives and mothers, and confined only to domestic chores. Their attempts at disrupting social conventions were important and significant steps toward establishing and normalising greater gender equality in all aspects of life.

Andrea Kee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, who works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as providing reference and research services.

Andrea Kee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, who works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as providing reference and research services.NOTES

-

Alys Eve Weinbaum, et al., eds., “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device: Collaboration, Connective Comparison, Multidirectional Citation” in The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 305.24220904) ↩

-

Alys Eve Weinbaum, et al., eds., “The Modern Girl Around the World: Cosmetics Advertising and the Politics of Race and Style” in The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 25. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 305.24220904) ↩

-

Robert Hamilton Bruce Lockhart, Return to Malaya (London: Putnam, 1936), 116. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 959.5 LOC-[ET]) ↩

-

Weinbaum et al., eds., “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device,” 1. ↩

-

Su Lin Lewis, “Cosmopolitanism and the Modern Girl: A Cross-Cultural Discourse in 1930s Penang”, Modern Asian Studies 43, no. 6 (November 2009): 1385–86. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Rachel Leow, “Age as a Category of Gender Analysis: Servant Girls, Modern Girls, and Gender in Southeast Asia,” The Journal of Asian Studies 71, no. 4 (2012): 980. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Weinbaum et al., eds., “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device,” 5. ↩

-

Weinbaum et al., eds., “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device,” 9. ↩

-

Weinbaum et al., eds., “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device,” 9. ↩

-

Weinbaum et al., eds., “The Modern Girl Around the World,” 28, 30. ↩

-

Sarah E. Stevens, “Figuring Modernity: The New Woman and the Modern Girl in Republican China,” NWSA Journal 15, no. 3 (Autumn 2003): 84. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

《良友》was also distributed in Singapore. See Paul G. Pickowicz, Kuiyi Shen and Yingjin Zhang, eds., Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926–1945 (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 250, 258. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 302.2320951132 LIA) ↩

-

Chua Ai Lin, “Singapore’s ‘Cinema-Age’ of the 1930s: Hollywood and the Shaping of Singapore Modernity,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13, no. 4 (December 2012): 595, 597. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

Chua, “Singapore’s ‘Cinema-Age’ of the 1930s,” 595. ↩

-

Saw Swee-Hock, “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 1, Singapore Commemorative Issue 1819–1969 (March 1969): 43–44. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

Kung Yuseng, “Woman’s Corner. Revolt of the Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 22 August 1931, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Betty Lim, A Rose on my Pillow: Recollections of a Nyonya (Singapore: Armour Publishing, 1994), 17–18. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 920.72 LIM) ↩

-

Peter Lee, Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World, 1500–1950 (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2014), 253, 260. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 391.20899510595 LEE-[CUS]) ↩

-

Su Lin Lewis, Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920–1940 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 247. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no.: R 307.7609590904 LEW) ↩

-

Lee Chor Lin, In the Mood for Cheongsam (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet; National Museum of Singapore, 2012), 20. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 391.00951 LEE-[CUS]) ↩

-

Francis T. Seow, The Media Enthralled: Singapore Revisited (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 323.445095957 SEO) ↩

-

“Miss Tow Foo Wah”, “Skirts Too Short,” Malaya Tribune, 7 March 1931, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Evelyn”, “The Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 21 March 1931, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Miss Anxious”, “The Modern Girl and Her Fashions,” Malaya Tribune, 4 April 1931, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jay Bee, “Dancing,” Malaya Tribune, 14 October 1931, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Helen Chan, “The Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 20 October 1931, 14; “A Modern Chinese Girl”, “The Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 2 November 1932, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia Ah Keow, “The Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 22 September 1938, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Juliet Loh, “The Modern Girl,” Malaya Tribune, 24 September 1938, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Karen M. Teoh, Schooling Diaspora: Women, Education, and the Overseas Chinese in British Malaya and Singapore, 1850s–1960s, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 7–8. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 370.8209595 TEO) ↩

-

“Evelyn”, “The Modern Girl.” ↩

-

Lewis, Cities in Motion, 229. ↩

-

“Conservatism Must Give Way to Modern Ideals and Ideas,” Straits Times, 9 October 1938, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Adelina”, “The Ways of Girls,” Malaya Tribune, 28 March 1931, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Fascination of Careers for Malayan Chinese Girls,” Straits Times, 2 February 1939, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Spore’s First Girl Lift Attendant,” Morning Tribune, 1 May 1936, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Around Malaya,” Morning Tribune, 6 May 1936, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zola, “What Readers Are Saying: Girls & Unemployed Youths,” Malaya Tribune, 13 April 1938, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

G.S. Teo, “The Weaker Sex,” Malaya Tribune, 27 April 1938, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

C.T.C., “Girls in Offices,” Malaya Tribune, 4 May 1938, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Educated Female, “‘Zola’ Did Start Something,” Malaya Tribune, 20 April 1938, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sunny Girl, “Another Girl’s Views,” Malaya Tribune, 20 April 1938, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“She Shocked Father by Bobbing Her Hair,” Sunday Tribune (Singapore), 3 April 1949, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim, Rose on my Pillow, 20–24. ↩

-

Lewis, “Cosmopolitanism and the Modern Girl”, 1387. ↩

-

“Audi Alterem Partem”, “‘Unmarriageable’ Chinese Girls,” Malaya Tribune, 20 November 1931, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Goh Tong Liang, “Unmarriageable Girls,” Malaya Tribune, 20 December 1931, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Srikrishnan”, “Unmarriageable Girls,” Malaya Tribune, 7 December 1931, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

June Lee, “Chinese Girls Now Choose Their Husbands,” Straits Times, 20 July 1939, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee, In the Mood for Cheongsam, 123–24. ↩