Exhibiting Photography in Prewar Singapore

The founding of two camera clubs in 1921 created more opportunities to exhibit photographs in Malaya. Zhuang Wubin revisits three significant photo exhibitions in prewar Singapore and examines their implications.

Between the 1920s and the onset of the Japanese Occupation in 1942, there had been various efforts to organise photography exhibitions in Singapore that featured the works of European and Asian photographers. The organisers of each exhibition had their own agendas and reasons for staging the event. Their political affiliations and sources of patronage were also different. By revisiting these initiatives, we can piece together a narrative of pre-World War II Singapore through the conditions that made the staging of these exhibitions necessary and possible.

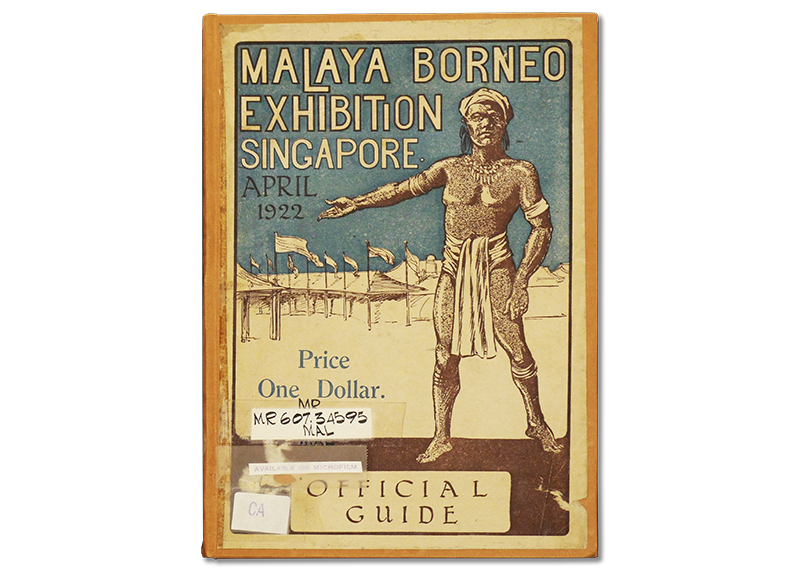

Malaya Borneo Exhibition, 1922

On 31 March 1922, the Malaya Borneo Exhibition opened to much fanfare on reclaimed land adjacent to the Telok Ayer basin. Occupying 65 acres (around 263,046 sq m), the colonial spectacle was put together in less than six months. After several extensions, the fair ended on 17 April.

Governor of the Straits Settlements Laurence Guillemard conceived the idea for the exhibition. As he noted in the souvenir guide, its objective was to “bring together, for the first time in history, representatives of all classes from the two important Malayan countries under British influence”, namely British Malaya and Borneo, so that “by interchange of ideas and discussion of matters of interest to each, considerable mutual benefit might be derived by all, and a revival of local trade possibly stimulated”.1

However, in truth, the revival of colonial trade was probably the key reason for organising the exhibition. In Singapore, the post-World War I euphoria quickly gave way to a recession in 1920, which only started easing in 1922.2 There was also the minor matter of coinciding with the visit by the Prince of Wales who officiated the opening. The souvenir guide also highlighted that the exhibition would show the prince the “natural resources and possibilities of Malayan countries under British influence, and to illustrate as far as possible some of the characteristic features of these countries and their people”.3

To that end, plans were made for members of the Malay, Dyak and Murut communities to create life-size replicas of their traditional houses for display.4 While 42 Dyaks arrived from Sarawak to build their longhouse, the North Borneo Chartered Company, however, failed to round up enough men to re-create a Murut house.5 In any case, the Arts and Crafts Section remained one of the most popular exhibits at the fair, featuring some 20,000 items made by or belonging to the indigenous communities of Malaya and Borneo. Many of these items were also available for sale.6

The exhibition included performances to entertain visitors, such as Sulu and Dyak dances, mak yong and menora dance forms from Kelantan, boria theatre from Penang, mek mulung theatre and wayang kulit shadow play from Kedah, regimental band music and even a Tamil fire dance.7

Many major businesses in Singapore, such as Fraser and Neave, Robinson and Co., and Sime Darby and Co., participated in the Commerce Section and bagged medals and diplomas for their best products. This was the key objective for staging the fair in the first place.8

Outdoor events included boat races, football matches, “live” Terengganu boatbuilding demonstrations, a circus, a dog show, a zoo comprising animals from different “collections” and even Manila Carnival entertainment.9 Into that melee was an exhibit of photographs.

F. de la Mare Norris, government entomologist and assistant to the director of agriculture of the Federated Malay States, was instrumental to this photographic display. Norris had been elected president of the Malayan Camera Club (MCC) when it was established in Kuala Lumpur in 1921.10 In the same year, the Singapore Camera Club (SCC) was founded, which catered initially to Japanese amateur photographers in Singapore and Johor (this club is unrelated to the similarly named club formed in 1950 in Singapore).

When plans were drawn up for the Malaya Borneo Exhibition in Singapore, the organisers turned to the MCC for help due to its connection with the colonial milieu, instead of approaching the SCC. Norris was selected to chair the Photography (Amateur) Committee, which comprised non-Asian members, including his wife Muriel. (Norris also served as honorary secretary of the exhibition’s Agricultural Section Committee.)

In January 1922, an open call was held for submissions from “amateur photographers of all races” for the photographic display. At the time, amateur photography connoted an artistic pursuit as opposed to professional photography where practitioners engaged in photography for profit. One of the conditions stipulated was that the photographs had to be taken in either the Malay Peninsula or Borneo.11

Exhibitors could submit photographs in any of the seven classes (or categories): (i) pictorial photography; (ii) portrait studies; (iii) outdoor or fancy-dress portraits; (iv) nature studies; (v) native life studies; (vi) places of interest, and (vii) miscellaneous. The first three classes were “intended solely for work of a pictorial and artistic nature”, while “photographs exhibited merely for their interest or technique” should be submitted to the remaining classes.12 Not surprisingly, the winning submissions were dominated by Japanese practitioners of the SCC and British members of the MCC. Norris and his wife also won multiple awards.13

Professional photographers were not left out. A Photography (Professional) Committee was also set up to organise submissions from professional photographers. In that committee of five, two Asian names stood out: Lee Keng Yan (most likely Lee King Yan; 李镜仁) and S.K. Yamahata.14 Their inclusion suggests that by the early 1920s, Japanese and Chinese studio photographers had gained a foothold in Singapore’s photographic trade, and could no longer be sidelined by the colonial government or European studio owners.

The winners of the professional section were dominated by Japanese photographers who blended Japanese tradition with Western techniques, although the Chinese-owned Empire Studio (established by Low Kway Song in 1920) and Eastern Studio (founded by Lee King Yan in 1922; he had previously set up Lee Brothers Studio on Hill Street) also won awards.15

Selected photographs submitted to the two committees were displayed in one of the railway godowns on the exhibition grounds. One of the first portraits a visitor would have seen in the professional section was that of Lady Guillemard, wife of Laurence Guillemard, placed near a portrait of the Sultan of Johor. The power structure of the colonial society was made clear in a visual and spatial sense. On a superficial level, the close proximity of the two photos indicated an equal relationship between the British and Malay elites. The implication, however, is that it was the “protection” and tutelage of British colonialism that ensured the continuity of Malay power.

More crucially, the public display of photographs in the exhibition marked a significant attempt to utilise the amateur and professional pursuits of photography to advance the agenda of the colonial state. Photography was included in the array of displays and performances in the fair, which advertised and showcased the products and “development” of Malaya and Borneo, giving the impression that these were the result of “benign” British rule. In effect, photography was used by the British to visualise and shield the specific effects of colonialism. In the process of decolonisation and nation-building, the national elites retained a similar faith in photography, mobilising it for a variety of cultural, socio-political and diplomatic projects.16

Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition, 1935

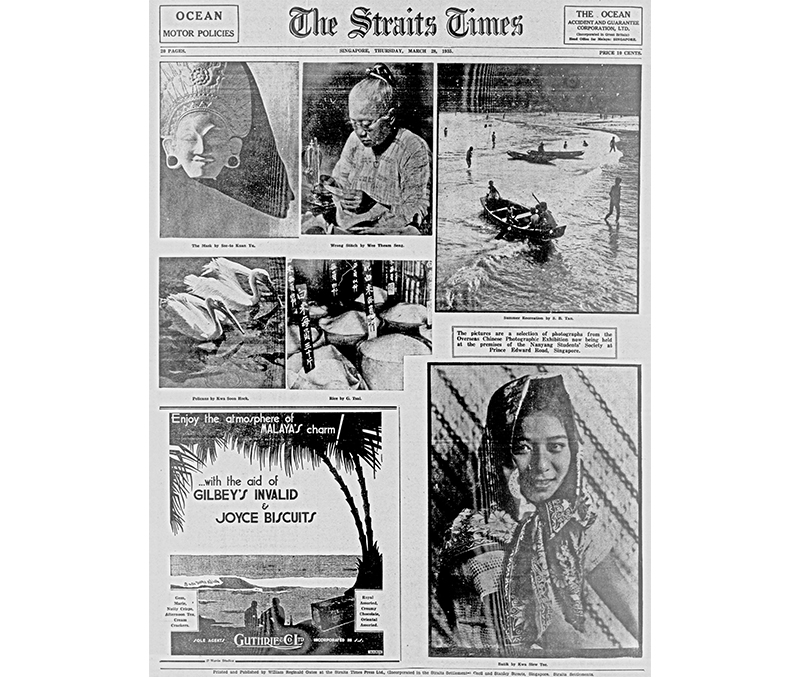

On 24 March 1935, the Chinese Consul-General to Singapore, Philip K.C. Tyau, presided over the opening of the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition. Newspaper reports hailed the exhibition as the “very first of its kind in Singapore” and the “first one promoted by the Chinese in Malaya”, presumably because it showcased the works of Chinese photographers residing in Malaya even though entries by photographers from Hong Kong were also included.17

By this time, the SCC and MCC had become inactive. And unlike the public display of photographs at the Malaya Borneo Exhibition in the previous decade, where works by the Japanese were featured, it had become less acceptable during the 1930s for Chinese photographers – who considered themselves cultural elites – to be seen on the same public platform as their Japanese counterparts. This was because Japan’s blatant aggression in China from the late 1920s had given rise to anti-Japanese sentiments among the Chinese communities in Singapore and a surge in nationalist feelings for the Chinese motherland.18

The exhibition was held at the premises of the Nanyang Chinese Students Society on Prince Edward Road. Founded in Singapore in 1919, the society was a self-help organisation targeted at overseas Chinese youths, with the aim of helping them eradicate bad habits, strengthen their physiques and propagate the national language.19 The exhibition organisers also invited Tyau to serve as its patron. These initiatives revealed the unmistakeable imprint of Chinese nationalism on cultural and artistic matters in Singapore.

The idea of staging the exhibition was first mooted by a small group of photo enthusiasts at a New Year’s Eve dinner in 1933.20 Application details were disseminated throughout February 1935 via the network of Chinese photo studios in Singapore, and also through Keng U photo studio in Kuala Lumpur and Kong Hing Cheong in Penang.21

Kwa Soon Hock, an employee of the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC), was responsible for receiving the submissions.22 Despite the hefty entry fee of $1, the organisers received 352 prints from 38 entrants in Sitiawan, Seremban, Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Perak, Penang, Terengganu, Singapore and Hong Kong. After two rounds of selection, 83 prints were shortlisted.23

The participating photographers included well-known amateurs like Chia Boon Leong and OCBC general manager Kwa Siew Tee, who was the father of Kwa Soon Hock. Chia was no stranger to photography exhibitions, as he had earlier received two awards at an exhibition organised by the SCC in 1926.24 Kwa Siew Tee, on the other hand, was a member of the Royal Photographic Society, having been elected in 1913. He was made associate of the society in 1935,25 and in 1940, he was appointed Justice of the Peace.26

The opening was chaired by OCBC manager Chew Hock Leong, who also contributed an essay to the exhibition catalogue.27 In his address, Chew explained the objectives for organising the exhibition. According to him, the organisers felt that by popularising photography and encouraging “fellow photographic comrades” to focus on the exploration of art, their works would become more artistic and in time measure up against the standard of photographers in advanced nations.28 There is a strong element of nationhood in Chew’s speech, even though it is not easy to clearly delineate what “nation” meant to the organisers, the participating photographers and the exhibition visitors at the time.

The presence of Tyau and the choice of exhibition venue suggest that the organisers felt a certain affinity with the affairs of China. They identified themselves as huaqiao (华侨; overseas Chinese) and named the exhibition accordingly.

When describing the exhibits, the English newspapers of the day tended to mention their aesthetics, valorising some of the works as exemplars of pictorial art.29 In contrast, an article in the Chinese newspaper Union Times (总汇新报) on 25 March 1935 singled out a particular photograph by Li Ying (黎英). The writer praised the work for its ability to transport viewers to the actual scene of combat where brave soldiers of the 19th Route Army in the Republic of China fought against the enemy. The photograph had been titled with a Cantonese curse word, most likely to reflect how strongly the photographer felt about the war in China.30 The 19th Route Army was lauded when it put up fierce resistance against the Japanese troops who attacked Shanghai on 28 January 1932 (known as the January 28 Incident or Shanghai Incident). This event was the precursor to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45).

The exhibition was hailed as a “thorough success”, with some 2,000 people visiting the show before it ended on 31 March. As a result of the exhibition, the Oversea Chinese Photographic Society was formed in March 1936. It was exempted from registration by the colonial state, suggesting a certain degree of closeness that some of its members enjoyed with the British authorities. Members included prominent figures associated with Chinese banks in Singapore, such as Chew Hock Leong, Kwa Siew Tee and Teo Teow Peng, who was director of Sze Hai Tong Bank.31 Police photographer Liew Choe Hoon (or Liew Chor Hoon), an early initiator and participant of the exhibition, also became a member.32

Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition, 1939–40

On 7 July 1937, two years after the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition was held, the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out between China and Japan. As a result, Chinese communities in Southeast Asia became even more connected to the fate of the motherland.

In Singapore, the Singapore China Relief Fund Committee (SCRFC) was set up in August 1937 with prominent businessman and philanthropist Tan Kah Kee as president. A year later, in October, Tan helped to establish the Southseas China Relief Fund Union (SCRFU) and became its chairman. By January 1939, the SCRFC had formed over 20 sub-committees with more than 200 branches across the island, extending its collection of funds beyond the city centre of Singapore. This caused much concern to the colonial authorities as the SCRFC was increasingly functioning “like a political party machinery” at the grassroots level.33

In 1938, Japan gained control of Xiamen and Guangdong, two major hometowns of the overseas Chinese in Nanyang (Southeast Asia). By then, China had lost most of its seaboard connections to the outside world. To open up a route so that war supplies could enter China, the 1,154-kilometre-long Yunnan-Burma Highway (also known as the Burma Road), linking Lashio in eastern Burma (Myanmar) with Kunming in China, was rushed through for completion by some 200,000 Burmese and Chinese labourers.

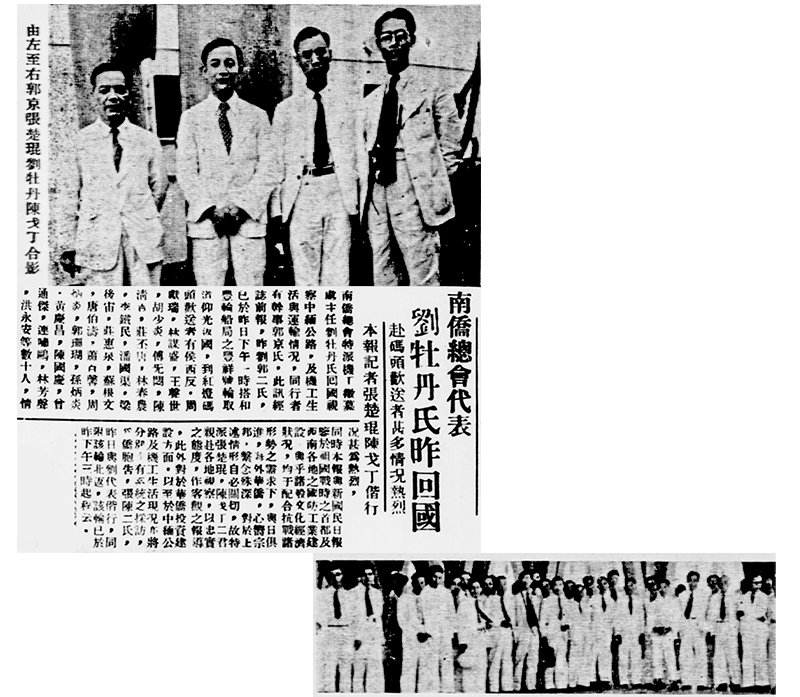

Traversing treacherous terrain, the highway became serviceable for heavy transportation vehicles at the start of 1939. However, China still lacked skilled drivers and mechanics to work along the route. In early 1939, the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) government of the Republic of China appealed to the SCRFU for help. Around 3,200 people across Nanyang, not all of whom were ethnic Chinese, answered the call. Some gave up well-paying jobs while a few women disguised themselves as men to serve in China’s war relief efforts.34

Knowing that there would be interest among readers in Malaya, the Chinese dailies Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商报) and Sin Kuo Min Jit Poh (新国民日报) sent two journalists – Chang Ch’u-k’un (Zhang Chukun; 张楚琨) and Chen Geding (陈戈丁) – to report on the Yunnan-Burma Highway. Setting sail for Rangoon (Yangon) in August 1939, they spent the next two months filing dispatches along the route. The two men also took more than 1,000 photographs which Chen brought back on his return trip via Vietnam.

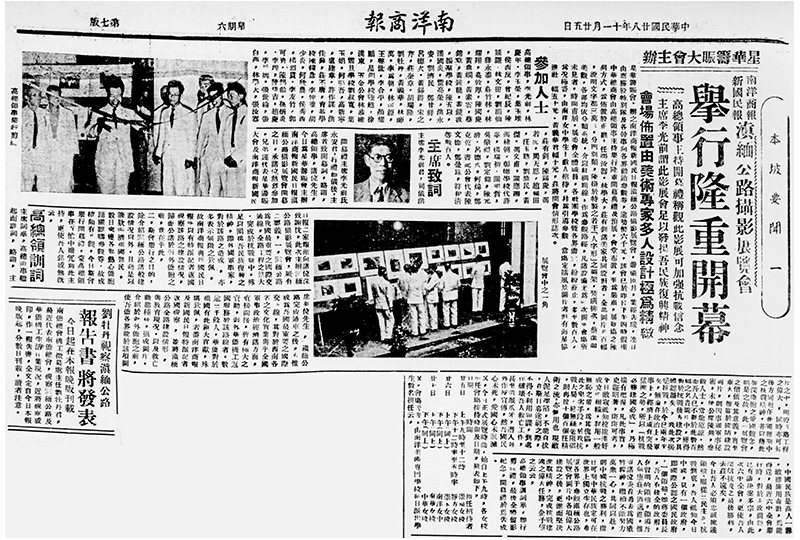

With Tan Kah Kee’s support, the SCRFC decided to mount a photo exhibition to help raise funds for China and at the same time provide visitors with a comprehensive experience of the highway.35 An exhibition committee was quickly assembled, with Lee Kong Chian, Tan’s son-in-law, as president.

A three-tier ticketing structure was established: the honorary ticket costing five Straits dollars and came with a complimentary print, while the special ticket was a dollar each and the normal ticket cost 20 cents. The Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (SCCC) served as the exhibition venue where tickets were sold for the duration of the exhibition.36 Prints were available for purchase, and all proceeds from the tickets and prints were channelled into the relief fund.

Tapping into SCRFC’s vast network, activists combed the island, cajoling all segments of Chinese society to purchase tickets. By the time the exhibition opened at the SCCC on 24 November 1939, over 6,000 Straits dollars had been raised from ticket sales.37

It is unclear if the Oversea Chinese Photographic Society was involved in the exhibition, but members of the Society of Chinese Artists (SOCA) certainly were. The SOCA was formally established in January 1936, with permission granted by the colonial authorities. In 1938, it helped to establish the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) with member Lim Hak Tai appointed as the founding principal.38 Lim also headed the exhibition’s installation committee, while SOCA president Tchang Ju-ch’i (张汝器) and fellow member Zhuang Youzhao (庄有钊) became his deputies.39 The three men were responsible for the exhibition’s clean and modern design. They utilised specially made free-standing panels to display the prints. Red, silk-fabric ropes were used to direct the viewers through the exhibition venue.40

The exhibition featured some 300 photographs, systematically organised into categories such as the lives and training of the drivers and mechanics, their transportation work, conditions of the highway, sights in Burma, peoples and customs of the borderlands, Chinese historical sites, tourist attractions and educational facilities relocated to Kunming due to the war, among others.41

To reach the masses, the organisers promoted the exhibition by connecting some of the sights captured in the photographs with scenes from the ever-popular Chinese classic, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义).42

Originally slated to close on 27 November, the exhibition was extended to 29 November. The Malaya Tribune reported that some 13,000 people had visited the exhibition at the SCCC.43

The exhibition was then moved to the Happy World amusement park to coincide with the SCRFC fundraising fair held there from 1 to 3 December; each ticket was priced at 10 cents. To attract non-Chinese visitors, the text and captions accompanying the photographs were translated into English.44 On 3 December, in just three hours from 7 to 10 pm, over 500 exhibition tickets were sold. Due to popular demand, the exhibition was extended another week and ended on 10 December.45 In early 1940, the exhibition toured Melaka, Muar and Batu Pahat, again to a rousing reception.

The Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition was probably one of the most visited photographic exhibitions in Malaya during the first half of the 20th century. The exhibition attempted to illuminate its subject matter by organising the photographs into different thematic sections. The exhibition also involved different strata of Chinese society, including NAFA students who maintained order at the venue and volunteers from Chinese-medium schools who served as attendants.

The exhibition helped to visualise and strengthen the connection between the overseas Chinese in Malaya and Singapore and the emerging nation in China. This link would have serious consequences during the Japanese Occupation and the subsequent era of decolonisation.

In the early Occupation years, the Japanese military systematically targeted the Chinese for their alleged support of the movement in an exercise known as Sook Ching (肃清; “purge through cleansing”). From 21 February to 4 March 1942, Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 in Singapore were ordered to report at various mass screening centres, with those suspected of being anti-Japanese subsequently executed.

After the war, nationalist and anti-colonial sentiments continued to rise. What it meant to be Chinese in Malaya and Singapore (and how one’s relationship with China was perceived) was a highly contentious issue, which directly affected one’s survival.

Different and Yet the Same

In revisiting these three photo exhibitions – held in 1922, 1935 and 1939–40 respectively – in pre-war Singapore, we see a definite shift in patronage and political affiliations that facilitated these events. To an extent, these exhibitions enabled participating photographers and visitors to visualise and imagine a sense of place and loyalty, whether it was directed at Britain, China or Malaya. What remained unchanged, however, was the involvement of political and cultural elites in organising and mobilising these exhibitions for their own motivations and desires.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2017–18). Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2017–18). Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.NOTES

-

Guide to the Malaya Borneo Exhibition 1922 and Souvenir of Malaya (Singapore: Malaya Borneo Exhibition, 1922), 5. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 607.34595 MAL; Microfilm nos. NL9852, NL27451) ↩

-

Constance Mary Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2020), 221. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

Guide to the Malaya Borneo Exhibition 1922 and Souvenir of Malaya, 5. ↩

-

Guide to the Malaya Borneo Exhibition 1922 and Souvenir of Malaya, 61. ↩

-

“Malaya Borneo Exhibition: Progress Reported,” Singapore Free Press, 23 March 1922, 183. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“M.B. Exhibition: Borneo’s Native Crafts,” Singapore Free Press, 13 April 1922, 232. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malaya Borneo Exhibition: Progress Reported.”; “M.B. Exhibition: Borneo’s Native Crafts.”; “Exhibition Closed,” Malaya Tribune, 18 April 1922, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Guide to the Malaya Borneo Exhibition 1922 and Souvenir of Malaya, 67. ↩

-

“Malaya-Borneo: Arts and Crafts Section of Exhibition,” Straits Times, 5 April 1922, 9–10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press, 13 August 1921, 12; “Government Appointments,” Straits Times, 24 May 1920, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malaya-Borneo Exhibition: Amateur Photographic Section,” Malaya Tribune, 20 January 1922, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Exhibition,” Malaya Tribune, 7 April 1922, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Guide to the Malaya Borneo Exhibition 1922 and Souvenir of Malaya, 19. ↩

-

“Western Arts,” Singapore Free Press, 8 April 1922, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zhuang Wubin, Shifting Currents: Glimpses of a Changing Nation (Singapore: National Library Board, 2018), 12–16. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 915.957 KOU-[TRA]); Zhuang Wubin, Documenting as Method: Photography in Southeast Asia [doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster, 2021], 67–73, https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/v3392/documenting-as-method-photography-in-southeast-asia. ↩

-

“First of its Kind in Singapore,” Malaya Tribune, 25 March 1935, 12; “Photographic Exhibition,” Straits Times, 27 February 1935, 12; “Photographic Exhibition,” Malaya Tribune, 7 February 1935, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

林孝胜 [Lin Xiaosheng], “四海同心 义薄云天—抗日救亡运动” [“Anti-Japanese Movement”], in 新加坡华人通史 = A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, ed. 柯木林 [Kua Bak Lim] (Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 2015), 559. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Chinese RSING 959.57004951 GEN-[HIS]) ↩

-

南洋青年励志学社 [Nanyang Chinese Students Society], “南洋青年励志学社组织缘起” [“The Origins of Organising the Nanyang Chinese Students Society”] (vol. 8), in 马华新文学大系 [Anthology of Malayan Chinese New Literature], ed. 方修 [Fang Xiu] (Hong Kong: World Publishing Co., 2000), 534–35. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Chinese RSING C810.08 MHX) ↩

-

“Photo Exhibition: Artistic Work by Overseas Chinese,” Singapore Free Press, 25 March 1935, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“本坡将有华侨摄影展览会” [“Singapore to Host Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 6 February 1935, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Chinese Photographic Exhibition,” Straits Times, 23 March 1935, 12; “华侨摄影展览会” [“Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 17 March 1935, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Camera Club,” Singapore Free Press, 6 July 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“List of Members of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain,” Photographic Journal 56 (1916): 36; Robert Chalmers, “Report of the Council for the Year 1935,” Photographic Journal 76 (1936): 284, The Royal Photographic Society, https://archive.rps.org/archive. ↩

-

“Certificates of Honour for Penang Malay and Chinese,” Straits Times, 5 July 1940, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Photographic Exhibition.” [Note: The catalogue exhibition includes the full listing of exhibits and the photographers, essays by writers experienced in the art of photography and halftone reproductions of some of the best works submitted. Thus far, no extant copy of this catalogue has surfaced.] ↩

-

“第一届华侨摄影展览会” [“First Edition of the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition”], Union Times, 25 March 1935, 2, National University of Singapore Library, http://lib.nus.edu.sg/sea_chinese/documents/union%20times/1935/1935_03_25.pdf. ↩

-

“Photo Exhibition: Artistic Work by Overseas Chinese”; Anak Singapura, “Notes of the Day,” Straits Times, 26 March 1935, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“第一届华侨摄影展览会” [“First Edition of the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition”]. ↩

-

“Photography: Singapore Chinese Form Society,” Singapore Free Press, 14 March 1936, 6; “For Photographers,” Malaya Tribune, 13 March 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“华侨摄影展览” [“Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 27 February 1935, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yong Ching-Fatt, Tan Kah-Kee: The Making of an Overseas Chinese Legend (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2014), 204–21. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 338.04092 YON) ↩

-

林孝胜 [Lin Xiaosheng], “四海同心 义薄云天—抗日救亡运动,” 567–70. ↩

-

“滇缅公路写真展览” [“Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 12 October 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“滇缅公路影展助赈 委员会昨成立” [“Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition to Aid Relief Fund; Committee Formed Yesterday”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 11 November 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“滇缅公路摄影展览会 举行隆重开幕” [“Grand Opening of the Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 25 November 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeo Mang Thong, Migration, Transmission, Localisation: Visual Art in Singapore (1866–1945) (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2019), 80, 102–103. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 709.5957 YAO) ↩

-

Tchang Ju-ch’i and Zhuang Youzhao (also known as U-Chow, Chong Yew Chao or Chuang Yew Chao) had set up The United Painters (朋特画社) in 1934, offering services such as advertisement graphic design and painting, oil painting, sculpture and badge design. ↩

-

“滇缅公路摄影展览会 举行隆重开幕” [“Grand Opening of the Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition”]. ↩

-

“星华筹赈会主办滇缅公路摄影展览 今日举行开幕及预展” [“Singapore China Relief Fund Committee Organises Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition; Opening and Preview Would Be Held Today”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 24 November 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“第7页 广告 专栏 2” [“Page 7 Advertisements Column 2”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 15 November 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Yunnan-Burma Road Pictures Exhibition,” Malaya Tribune, 1 December 1939, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“滇缅公路摄影展览会 明日移快乐世界举行” [“Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition Would Be Moved Tomorrow and Shown at Happy World Amusement Park”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 30 November 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“滇缅公路摄影筹赈展览 再度展期一周” [“Yunnan-Burma Highway Photo Exhibition for the Relief Fund Extended Again for Another Week”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 4 December 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩