The Final Hours of the Empress of Asia

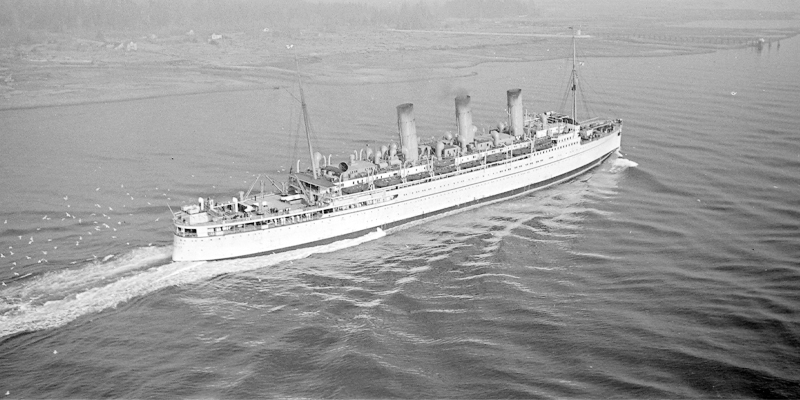

The Empress of Asia sank off Tuas in February 1942 while carrying troops to fight off the Japanese invasion. Dan Black recounts its final days.

A huge iron anchor has been part of the permanent exhibition at the National Museum of Singapore since 2015. About 2.4 m tall, it is originally from the RMS Empress of Asia, which was destroyed off Singapore in February 1942. At the time, the ship was transporting Allied troops to help reinforce Singapore’s defence during the Japanese invasion. The following story commemorates the 80th anniversary of this wartime loss.

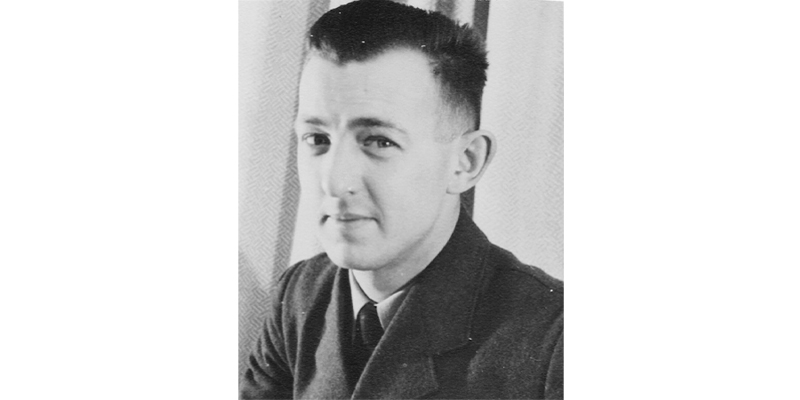

Geoffrey Hosken’s school exercise book was an odd choice for a seaman’s diary on a 16,909-ton troopship. Stamped in big black letters are six danger points for schoolchildren, starting with “Don’t run across the road without first looking both ways!” and ending with “Don’t forget to walk on the foot-path, if there is one!”1

The 25-year-old able seaman from Vancouver recognised the irony given his rough and tumble existence on the world’s oceans. But he really didn’t mind what others thought of his little green scribbler.

It was February 1942, and there were 30 pages to fill, several of which would describe the next 32 hours as his ship, the RMS Empress of Asia, steamed towards her death off Singapore.

With an unyielding pencil, Hosken wrote: “Wed., Feb. 4, 3 A.M… Lagging behind convoy as usual and cruiser keeps signalling to pick up speed for we are endangering the whole convoy.”

Worrisome words because the 30-year-old Canadian Pacific coal-burner was in dangerous waters off the east coast of Sumatra, in the narrow channel known as Bangka Strait. Just over a day’s sail from Singapore’s Keppel Harbour, the old “greyhound” of the Pacific was last in line with four other troopships in Convoy BM-12 which she had joined at Bombay (now Mumbai) on 23 January. The “firemen won’t or can’t get the steam,” noted Hosken. “Doing 12–13 knots and about a mile behind.” (Firemen are the men in the stokehold of a merchant ship who feed coal into the furnaces, heating the boilers that produce steam to drive the turbines.)

At the head of the convoy was the City of Canterbury, followed by the Dutch liner Plancius, the Devonshire, and the ex-French, 17,083-ton Félix Roussèl. Escorting were British cruisers HMS Exeter and HMS Danae, the Australian sloop HMAS Yarra, the Indian sloop HMIS Sutlej and two destroyers.

High above, a formation of twin-engine Japanese fighter-bombers scoured the sky and placid sea, paying attention to the islands and straits that forced convoys into single file.

In December 1941, while the Asia was off Africa between Freetown and the Cape of Good Hope, the Japanese shocked the world at Pearl Harbor and attacked the Philippines and Hong Kong. On 10 December, they sank Britain’s two capital ships, HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, based at Singapore. By Christmas, they had taken Kowloon Peninsula and Hong Kong, having forced British and Canadian troops to surrender after overwhelming them.

With Singapore as a major prize, the Japanese chose not to attack the island from the sea, avoiding the 15-inch guns, three of which could traverse 360 degrees. Instead, they landed in Thailand and northern Malaya on 8 December 1941 and advanced south with artillery, tanks and infantry on bicycles while aircraft attacked airfields and ground positions. By late January, around the time the Asia was collecting members of the British 18th Division at Bombay, the enemy had repeatedly bombed Singapore and was at the southern end of the peninsula.

While the Asia laboured through the Bangka Strait on 4 February, the Japanese were 11 days from forcing the British to surrender what many had thought was an impregnable fortress.

The night before Hosken noted the Asia’s lack of steam, Ordinary Seaman Jack Ewart had been in the crow’s nest 23 m above the water. At the time, Convoy BM-12, which had rendezvoused with Convoy DM-2, was in the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java. That was when the young Canadian thought he heard aircraft engines and picked up the phone to the bridge. Ewart was told he was probably hearing the engines of another ship off Asia’s starboard beam. When the ships reached the northern end of the Sunda Strait, several broke off and headed east to Batavia (now Jakarta) to support the Dutch colony while five ships headed northwest towards Bangka Strait.

Fourth Officer Walter Oliver had sailed most of the world’s oceans and earned the coveted master’s certificate. He had helped transport oil from the Dutch East Indies and once kept a cabin at Palembang, Sumatra. Oliver was familiar with the Singapore approaches and on 4 February the Asia’s position – “well in the rear” of the convoy – was apparent.2

Hosken, meanwhile, could see that his ship was not only last in line, but also visible with three massive smoke stacks. She carried the most number of military personnel: 2,235 compared to the Devonshire’s 1,673, had a crew of 413, and was heavy with military supplies.3

Painted wartime grey, the 180-metre-long Empress of Asia was not without firepower and her crew included 25 personnel drawn largely from the British Army and Royal Navy. To preserve the ship’s merchant and non-combatant status, these men, known colloquially as DEMS (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships), signed on as deckhands and were part of the crew. In addition to the DEMS, several crew members had gun training.

The anti-aircraft armament consisted of a 12-pounder (three-inch gun) fitted aft, close to the six-inch gun, six large-calibre Oerlikon guns, and 10 Hotchkiss light machine guns, six of which were secured within machine-gun nests near the bridge.4 The ship also had a parachute and cable anti-aircraft system launched by rockets. Missing was her Bofors anti-aircraft gun, which had been transferred to the British Army in North Africa.

The First Attack: Wednesday, 4 February

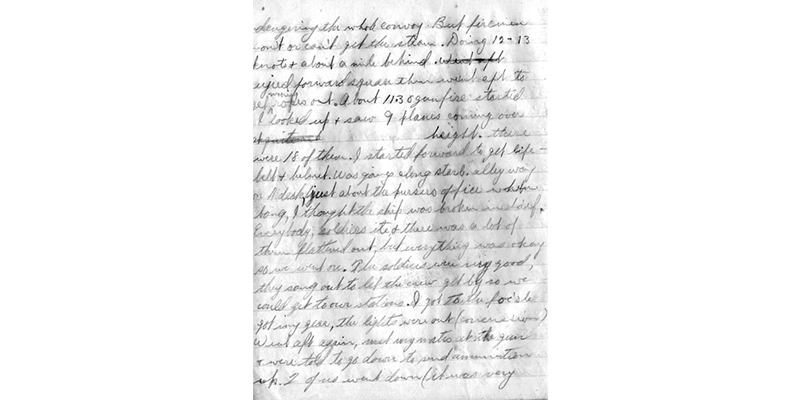

By 11 am, Hosken was helping prepare mooring lines for coming alongside at Singapore, approximately 525 km to the northwest. He detected what Ewart thought he had heard the night before: aircraft engines. “About 11:30 gunfire started and I looked up and saw nine planes coming over at quite a height. Then there were eighteen of them. I started forward to get lifebelt and helmet. Was going along the starboard alleyway on A deck, just about the purser’s office when bang, I thought the ship was broken in half.”

Captain John Watts of the British 18th Div. saw the aircraft at high altitude in “V” formation “with the sun glinting on their silver bodies”. He counted 27, nine to each “V” formation, proceeding north to south.5

Canadian Boy Seaman Geoff Tozer remembered five bombs hitting the water on the starboard side, three falling aft and two landing near the port side. Assigned to an anti-aircraft gun, he quickly realised the targets were beyond range.6

Hosken hurried aft to a gun position where he was sent below to an ammunition bunker. “2 of us went down (it was very scary). Had some boxes of shells hoisted up and we were told to come out…and keep a lookout by the gun.” He counted five enemy bombs; none of which were direct hits. “Two were near hits. No. 2 and 2A lifeboats were splintered by shrapnel. One piece landed right beside [Ordinary Seaman] Mike [Costello] and one near the gun aft.”

Sanitation Engineer John Drummond stated the concussion “smashed some large, square port glasses [windows] in the ship’s dining saloon and split iron tables in two”. The enemy, he added, was driven off by anti-aircraft fire and two Allied fighter planes. “But this gave away our position as we were only 24 hours sail from our Destination.”7

In his diary, Hosken wrote “the bloody firemen came up when the first bomb was dropped”, but returned below when told to do so by a priest.8 He does not identify the priest, but he was likely a chaplain attached to the British troops. Hosken did not specify how many of the firemen, who had signed on in the United Kingdom, appeared.9

Hosken wrote that 25 soldiers went below to keep watch. “It was a very scary episode and I hope never to experience it again.”10

In his report, dictated while imprisoned by the Japanese after the fall of Singapore, Watts stated: “… at the sound of the exploding bombs in the water on each side of the ship, it brought these people dashing up… onto the Fiddley Deck [the raised deck on top of the ship] from the depths of the Stokehold.” He stated this “worried us tremendously” and believed the absence of men from the stokehold for a “half hour”… reduced steam pressure and the ship “dropped considerably behind the main convoy”.11

In his official report, Captain John Bisset Smith, who commanded the Asia, made no mention of men in the stokehold leaving their posts when the bombing commenced on 4 February. He noted the ship was “allotted this position [last in line] on account of our steaming difficulties, the ship almost invariably dropping astern of station when fires were being cleaned”.12 Similarly, the report from Asia’s Chief Officer Donald Smith does not mention a loss of steam on 4 February.

Other available accounts support Hosken’s view or the claim that the ship had lost speed. One states that Exeter came alongside imploring the Asia to increase speed and another states some ex-miners among the troops went below to stoke the ship.13

“During the forenoon [4 February] the convoy split into two sections,” recalled Oliver. Two of the faster ships, the Devonshire and Plancius, escorted by Exeter and Sutlej, pulled away from the other three escorted by Danae and Yarra. “Twilight until daylight… everything remained quiet, with the convoy proceeding towards Singapore at twelve knots in clear tropical weather.” 14

The Second Attack: Thursday, 5 February

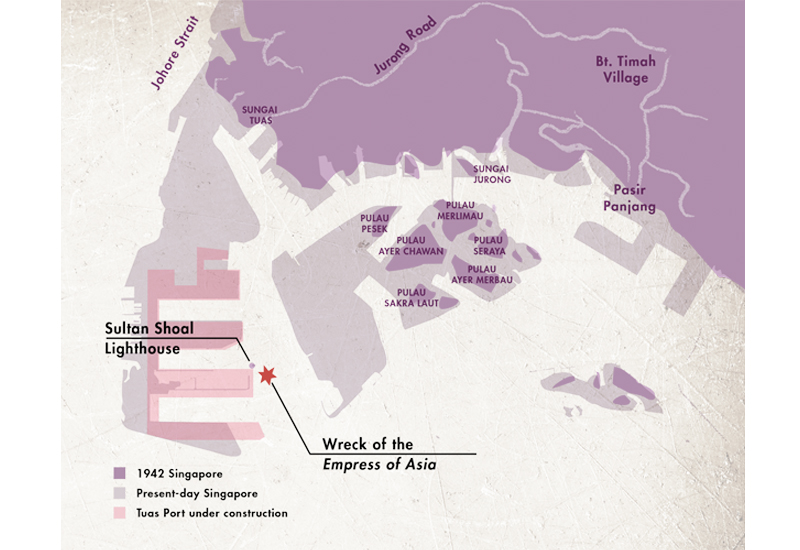

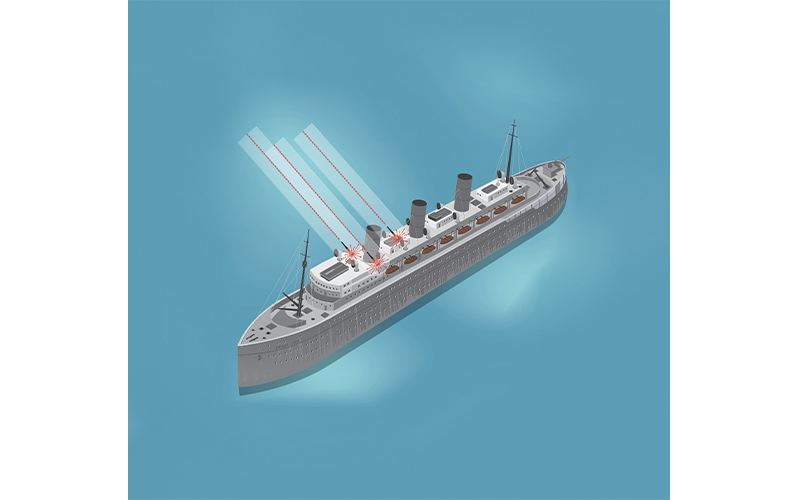

By around 10 am, the trailing section of Convoy BM-12 was approaching Sultan Shoal, 21 km from Keppel Harbour. The ships reduced speed as they prepared to embark harbour pilots. However, the pilot assigned to the Asia never made it on board.15 At 10.37 am, a large formation of aircraft was spotted, flying west to east.16 Minutes later, they attacked from all directions at low and high altitudes. The three troopships and their escorts opened fire. “Bombs started falling… and it was evident the ship had been singled out to bear the brunt of the attack,” reported the captain.17

Cadet Maurice Atkins was on the lower bridge during the attack. “There was this [enemy aircraft] coming down our bow with his machine-gun blazing, and I never felt so helpless in my life. He was heading straight for the ship – coming over the bow. All I could see was the machine-gun shells hitting the deck and bridge, and felt for sure one of them had my name on it.”18

Although she got a pilot on board, the Félix Roussèl suffered the first hit, but survived. The enemy aircraft then turned their attention on the Asia, which gave the two other troopships the chance to make port. “As each plane attacked, and when coming out of the dive, the bomb could be seen leaving the rack,” recalled Oliver. “Next the explosion, followed by the concussion. All these aircraft attacked from forward in line with the bow at incredible speed.”19

At 10.48 am, noted Oliver, the enemy scored its first hit. An incendiary bomb penetrated the upper deck between No. 1 and No. 2 funnels, exploding in the lounge. The blast inflicted heavy casualties among the troops below.20 Killed instantly was British soldier Ewen McKerchar, shy of his 28th birthday. “I had a firefighting crew working for me and while I was up in the lower bridge with the chief officer I was told to go and hook up the hoses to the hydrants and be ready to help,” recalled Atkins. “When we got there, there was no water.”21

“From the start… our guns put up an extremely good and steady barrage,” stated Oliver. “The barrels of the Bren guns became so hot they had to be discarded and replaced…”

Another bomb struck close to No. 1 funnel and exploded below deck, knocking out communications between the bridge and the after part of the ship. The fiddley deck was thick with smoke forcing the Bren gunners to the upper bridge railing facing the bow. “The concussion of all this firing set off many of our own rockets,” noted Oliver. “Some… flew horizontal around the bridge deck, adding… to the confusion. The rockets with the parachutes attached also took off on their own, at the wrong time, and landed with all the wiring back on deck.”22

Watts described one bomb passing over the bridge before smashing through the fiddley deck and exploding in the officers’ lounge. He noted it was an “oil bomb” weighing no more than 100 pounds (45 kg). The ship was “belching smoke from a short distance behind the bridge to the third funnel… We could see officers and men, blackened and burned, being passed and assisted through open windows of cabins and recreation rooms on the promenade deck.”23

Pantryman Douglas Elworthy, a member of the catering crew, was sprayed with hot, oily shrapnel. He was in the pantry below the lounge. In his diary, Hosken mentions a steward with a “belly full of shrapnel”.24 This was likely Elworthy, who died five days later.

“I can remember standing on the portside boat deck as we were trying to get some lifeboats away, and looking down fifty feet to the water at him [Elworthy] hanging on to a swamped lifeboat,” recalled Tozer. “I didn’t realise he was injured.”25

The Oerlikon guns ran out of ammunition while two Hotchkiss guns jammed, leaving the ship with her three-inch gun and small arms. A third bomb struck the officers’ quarters creating a fire. With the wheelhouse full of smoke and the floor buckling from heat, the engine room reported “gas forming in the stokehold”. The captain ordered its evacuation.

The chief officer noted that while “fire parties were immediately on the scene… no water was available… presumably due to the damaged mains”.26 By 11.25 am, the fires below decks were out of control.27

With the ship’s midsection and lifeboats ablaze, survivors continued to muster on the fore and after decks. At 12.15 pm, the order was given to abandon the bridge. The damaged stairs and ladders were useless so ropes were strung over the port side where 36 men escaped. Those on the starboard wing could not see through the smoke to the ropes so many jumped nine metres to the foredeck or 25 metres into the sea.28 Second Officer Cecil Crofts, one of the last to leave the bridge, fractured a leg jumping to the foredeck.

The fear of being machine-gunned was palpable. But “they left us alone and did not interfere… with the rescue work,” noted Oliver.

Atkins and Ordinary Seaman William McKinnon, 18, were ordered to lower loops of mooring line over the port side, an action that likely saved lives. When their time came, both slid down together.29

Amid falling embers, Ewart and Seaman Tim Cameron helped Crofts over the side and into a raft that reached Sultan Shoal. Cameron and Ewart were removed on the Danae.

Meanwhile, the Australian sloop Yarra, commanded by Captain Wilfred Harrington, was manoeuvred next to the doomed ship. Hosken noted that 1,600 men, including him, were rescued by the sloop, although some estimates are higher.30 Other vessels assisted, but without the Yarra hundreds could have perished.31

The Asia then drifted southeast of Sultan Shoal where anchors were dropped. “Before completely abandoning the afterdeck, the ammunition for the six-inch gun and the remainder from the twelve-pounder had to be thrown overboard. Only two lifeboats were intact,” noted Oliver. “Both… were launched; one made it, one capsized.”32 Oliver boarded the Yarra, but while checking the Asia’s lower decks, he found a dedicated engine room crewman who said he had not received the evacuation order.

By 1 pm, the ship was abandoned.

Of the 2,648 men on the Asia, 16 soldiers and four crew members died, and 238 were injured as a result of the attack. The enemy, it’s believed, lost two planes.33 The Asia eventually sank in relatively shallow water.

On 9 February, the morning after the Japanese crossed the Johor Strait, the ship’s catering crew volunteered to work for the Civil Medical Services in Singapore. Most served at the General Hospital until 17 February, while seven others worked at the Miyako Hospital (previously known as the Mental Hospital) until 25 April; all were subsequently interned at Changi Prison until the war’s end. Other crew remained at a military camp until instructed to leave the island. On 11 February, before the British surrendered on 15 February, these men, including Hosken, Oliver, the captain and chief officer, escaped Singapore on three small coastal vessels. Two of these vessels managed to reach Batavia while the third ran out of fuel and ended its journey in Sumatra. Its passengers and crew fled overland through the jungle to the Sunda Strait and eventually reached Batavia.

As for the Asia, various salvage efforts were undertaken over the years. In 1998, one such effort retrieved, among other things, the ship’s anchor, which is now on display at the Singapore History Gallery of the National Museum of Singapore. In 2020, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore issued a notice of work to remove the wreck. The wreck has since been cleared.

Dan Black is former editor of Legion Magazine, a publication on Canada’s military history. He has written many editorials and feature articles on Canada’s military past and present for the award-winning magazine. His third book, Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War, was published in 2019. He is currently working on a book about the Empress of Asia with researcher Nelson Oliver. (Photo courtesy of Gordon MacKay)

Dan Black is former editor of Legion Magazine, a publication on Canada’s military history. He has written many editorials and feature articles on Canada’s military past and present for the award-winning magazine. His third book, Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War, was published in 2019. He is currently working on a book about the Empress of Asia with researcher Nelson Oliver. (Photo courtesy of Gordon MacKay)NOTES

-

Geoffrey Hosken, Diary, 3 November 1941 to 19 April 1942. ↩

-

Walter Oliver, Loss of the Empress of Asia (Unpublished memoir, 1978), p. 98. ↩

-

Some sources state 416, but three crewmen left prior to Singapore. ↩

-

An account by Asia Captain John Bisset Smith lists six Oerlikons, eight Hotchkiss, a six-inch gun, three-inch anti-aircraft gun, four PAC rockets, and depth charges. ↩

-

Manuscript of “Empress of Asia” story dictated by Captain J. Watts to J.T. Carney in River Valley Camp, 1942, courtesy of Helen Watts. ↩

-

Geoff Tozer, Journal, 4 February 1942. ↩

-

John Drummond, Journal, 4 February 1942, p. 1. ↩

-

Hosken, 33. ↩

-

There were 70 firemen in the stokehold, plus 48 trimmers and 18 greasers. ↩

-

Hosken, 32–33. ↩

-

Watts, 11. ↩

-

Captain John Bisset Smith. 1942A. Commander’s Report, SS Empress of Asia. Voyage 151/3. Report to Canadian Pacific on final voyage, p. 1, 4 February 1942. ↩

-

William Hanson, My War Experience, 1939–1945, Far East Prisoners of War website, Ron Taylor@far-eastern-heroes.org.uk; William Harris, Imperial War Museum, Conrad Wood interview, 15 May 1989, Cat. No. 10704. ↩

-

Oliver, 98. ↩

-

Oliver, 99. ↩

-

Watts, 14; Oliver, 99. ↩

-

Smith, 1. ↩

-

Maurice Atkins, Interview, 29 January 2021. ↩

-

Oliver, 99. ↩

-

Oliver, 100. ↩

-

Atkins, Interview. ↩

-

Oliver, 100. ↩

-

Watts, 17. ↩

-

Hosken, 37. ↩

-

Geoff Tozer, Email to Nelson Oliver, 20 December 2001. ↩

-

Chief Officer Donald Smith. 5 February 1942. SS Empress of Asia Voyage 155/3. Chief Officer’s Report to CPR. ↩

-

Smith, Commander’s report. ↩

-

Oliver, 101. ↩

-

Atkins, Interview. ↩

-

The profile of Captain Wilfred Harrington in the Australian Dictionary of Biography states that 1,804 men were rescued. ↩

-

The Yarra was destroyed on 4 March 1942 while defending a convoy in the Indian Ocean. ↩

-

Oliver, 102. ↩

-

Oliver, 102; Nelson Oliver, Empress of Asia files. ↩